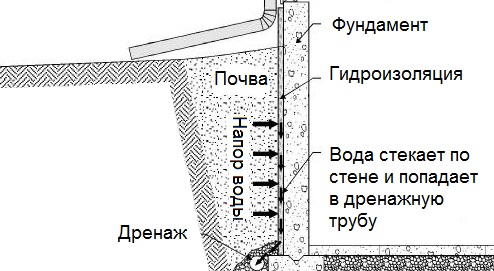

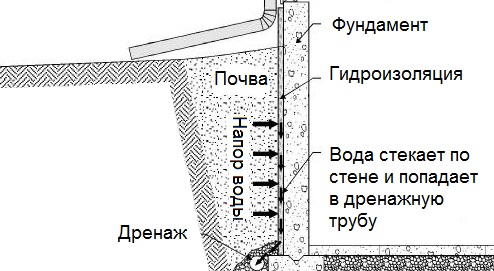

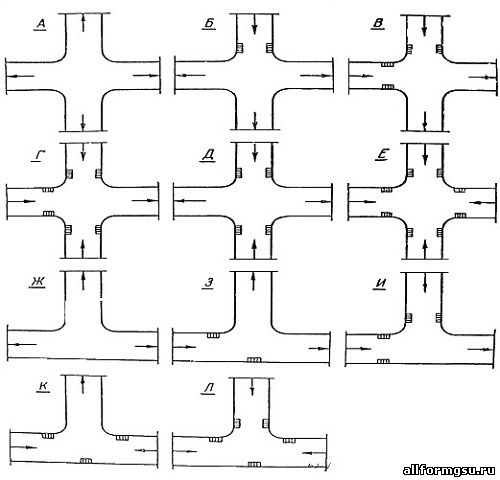

Общие условия выбора системы дренажа: Система дренажа выбирается в зависимости от характера защищаемого...

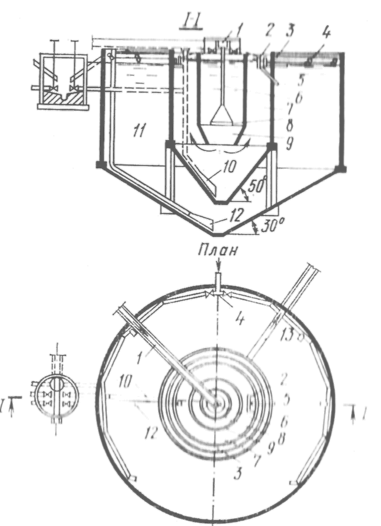

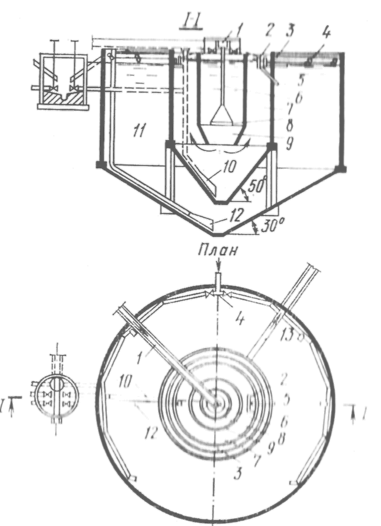

Типы сооружений для обработки осадков: Септиками называются сооружения, в которых одновременно происходят осветление сточной жидкости...

Общие условия выбора системы дренажа: Система дренажа выбирается в зависимости от характера защищаемого...

Типы сооружений для обработки осадков: Септиками называются сооружения, в которых одновременно происходят осветление сточной жидкости...

Топ:

Основы обеспечения единства измерений: Обеспечение единства измерений - деятельность метрологических служб, направленная на достижение...

История развития методов оптимизации: теорема Куна-Таккера, метод Лагранжа, роль выпуклости в оптимизации...

Когда производится ограждение поезда, остановившегося на перегоне: Во всех случаях немедленно должно быть ограждено место препятствия для движения поездов на смежном пути двухпутного...

Интересное:

Мероприятия для защиты от морозного пучения грунтов: Инженерная защита от морозного (криогенного) пучения грунтов необходима для легких малоэтажных зданий и других сооружений...

Инженерная защита территорий, зданий и сооружений от опасных геологических процессов: Изучение оползневых явлений, оценка устойчивости склонов и проектирование противооползневых сооружений — актуальнейшие задачи, стоящие перед отечественными...

Аура как энергетическое поле: многослойную ауру человека можно представить себе подобным...

Дисциплины:

|

из

5.00

|

Заказать работу |

Содержание книги

Поиск на нашем сайте

|

|

|

|

Adult males and females [of the Sperm Whale] have lifestyles so distinct that they might be separate species. The males leave tropical waters each summer and voyage into the highest latitudes … but females and young seldom venture more than 40° from the equator.

—LYALL WATSON, Sea Guide to Whales of the World 98

Heterosexual mating is anything but the “natural,” effortless activity that it is often portrayed as. There are many ways that sexual interactions between males and females are avoided, exacerbated, or generally fraught with problems. In numerous animals, for example, it almost seems that the social organization and behaviors of the species have been designed to keep males and females apart and prevent reproduction—or at least make it difficult. Consider sex segregation: partial or total separation of males and females is a surprisingly prevalent form of social organization in the animal world. Various forms of sex segregation occur in mammals and birds of all types, though separation of the sexes is especially prevalent in species such as hoofed mammals that have promiscuous or polygamous mating systems (where individuals mate with more than one partner). Often the only time that the two sexes come together is to mate, sometimes for only a few days or months out of the year—the rest of their time is spent living entirely apart. Even “harems”—in which one male associates with a group of females and often prevents other males from gaining access to them—are not the quintessential example of heterosexual mating opportunity that they are usually thought to be. Scientists studying “harems” in a number of species such as sea lions and some hoofed mammals have found that these groups do not always form as a result of heterosexual attraction or males “controlling” females (and thus the term is somewhat inaccurate). Rather, females prefer to associate with each other and therefore they congregate in relatively autonomous groups of their own; males that participate in breeding then end up associating with such groups out of necessity.99 In addition to social and spatial segregation—living in separate groups or habitats—sex segregation can also be seasonal or migratory. It may occur only during the nonbreeding season, for example, or involve separate migratory journeys or latitudinal destinations for males and females (for example, in Northern Elephant Seals and Kestrels). One of the most extreme forms of “sex segregation” occurs in several species of marsupial mice: all the males die a few days after the mating season, so that when females give birth there are no adult males left in the population.100

Sex segregation during the breeding season is often facilitated by a phenomenon known as sperm storage: most female animals have one or more special organs or sites in their reproductive tract that allow them to store a cache of sperm (from a prior mating) for a long time, using it later to “inseminate” themselves while forgoing heterosexual copulations. Birds and reptiles have special glands that allow them to do this. Female Ruffs, for example, often leave the breeding grounds (after having mated with males) and migrate northward, laying their eggs several weeks later by fertilizing them with stored sperm. In some birds such as the fulmar, sperm may be stored by females for up to eight weeks, while in reptiles (as well as insects) sperm stored in females may remain viable for much longer, up to several months or even years. Female garter snakes, for instance, are able to keep sperm for up to three to six months after mating with a male. In fact, females in this species usually do not ovulate until two to five weeks after their first mating in the spring. They may even become pregnant without mating at all that season, simply by using sperm from a copulation that took place the previous fall before hibernation. The record for sperm storage is held by the female Javan wart snake, who can store sperm for up to seven years! In mammals, sperm is generally “stored” for shorter periods (although some bats can do so for more than six months) and may be kept in “crypts” on the cervix or inside the uterus. Recent work has also shown that females in most species can control, through behavioral, anatomical, and physiological mechanisms, which portion of the sperm (if any) is stored and/or utilized for fertilization.101

A phenomenon known as delayed implantation also enables males and females to spend long periods away from each other. In nearly 50 mammalian species (including seals, bears, other carnivores, marsupials, and some bats) the fertilized egg does not implant right away. It remains in “suspended animation” for several months, after which it implants and begins its regular development. The delay extends the pregnancy by two to five months in seals and up to ten to eleven months in badgers, fishers, stoats, and related small carnivores. In seals, this allows females to spend a longer time out at sea—often completely separate from males—and permits them to optimize the timing of their pregnancies and to take advantage of more favorable times of the year for birthing and pup-raising. Some species of bats also have delayed embryonic development, in which the fertilized egg experiences a temporary cessation of development after implantation.102

In fact, delayed implantation as well as sperm storage (among a variety of other factors) effectively result in a separation and reordering of key reproductive events in many vertebrates, and consequently an “uncoupling” of male and female reproductive cycles. We are used to thinking of breeding as an ordered progression, one stage leading inevitably to the next: ovulation followed by mating followed by fertilization followed by pregnancy followed by birth (or egg laying). However, there are often significant gaps and rearrangements of these events: sperm storage can temporally separate mating from fertilization, while delayed implantation separates fertilization from fetal development during pregnancy. As noted above, sperm storage can also result in ovulation taking place after insemination, and in other animals, further rearrangements occur. In birds, for example, “pregnancy” or the development of the egg inside the mother’s body actually precedes fertilization: the egg yolks are already quite large (and may cause a noticeable bulge and weight increase in the female) prior to being fertilized. In fact, the eggs can be laid without ever being fertilized—this is what allows females in homosexual pairs to produce (infertile) eggs. In most fishes, “pregnancy” ends, rather than begins, with mating: the eggs develop within the female’s body and are then laid or discharged when ready to be fertilized (i.e., fertilization typically takes place outside the female’s body).103 In addition to these delays and reordering of reproductive events, breeding can also, of course, be interrupted or terminated at any of these stages—this will be discussed in the next section, when we look at naturally occurring forms of birth control.

Another common misconception about animal heterosexuality is that only females experience periodic hormonal fluctuations in their reproductive biology. In fact, many male animals also have sexual cycles, entailing considerable periods in which they are sexually inactive and living separate from females. Occasionally, male and female sexual cycles are poorly synchronized or not optimal for breeding, as sometimes happens in Ostriches and Lovebirds. Male cycles are found in a wide range of animals, including primates, deer, seals, and numerous bird species, and usually entail a yearly, rather than a monthly, periodicity. In some instances, dramatic physical and physiological changes are involved. Male Wattled Starlings, for example, undergo regular periods of “balding” (feather loss) and wattle development, and males of many other bird species develop dramatic nuptial plumages associated with breeding. Male Squirrel Monkeys become “fatted” during the peak of their sexual cycle, while male Elephants experience “musth,” involving a whole host of changes such as glandular secretions, increased aggression, and rumbling vocalizations.

The significance of male sexual cycles has often been lost or overlooked under sexist biological theories, which tend to emphasize aspects of animal biology that confirm the unflagging “virility” of male animals, to the exclusion of those things that underscore the similarities between male and female sexuality. In fact, reproductive traits that are usually thought to be exclusively male or female can be found in members of the opposite sex in at least some species. Male pregnancy occurs in sea horses, for example, while lactation—milk production from fully functional mammary glands—was recently discovered in male Dayak fruit bats.104 Females, for their part, can carry sperm within their bodies and “inseminate” themselves (as discussed above) or may possess elongated, phalluslike clitorides that can undergo erections (this is found in numerous mammals, including Spotted Hyenas, moles, and Squirrel Monkeys, as well as several flightless birds).105 Some animals (e.g., Seals, Bears, Squirrels) even have a clitoral bone, homologous to the male’s baculum or penis bone in these species; in female Walruses, this bone may be over an inch long. Female pipefish and Japanese sea ravens (a kind of fish) even have extendable genital organs used to penetrate or retrieve sperm from their male partners.106

When males and females do manage to get together, a formidable set of obstacles often stands in the way of achieving sexual contact and, ultimately, reproduction. Refusal or indifference by either the male or female partner is widespread and routine in the animal kingdom, and heterosexual matings are often “incomplete” in the sense that they do not involve erection, genital contact, ejaculation, and/or insemination. In one study of Chaffinch heterosexual copulations, for example, every “complete” and “incomplete” mating attempt was logged: out of 144 attempts, only 75 (52 percent) involved mounting with full genital contact (and therefore could potentially have led to fertilization). Of the remaining “unsuccessful” attempts, 76 percent entailed no mounting at all because one or both partners fled before copulation could take place, 9 percent involved the male mounting without attempting to make genital contact, in 8 percent mounting was terminated when the female refused to continue (in some cases after being pecked by the male), in 5 percent of the mounts the male slipped off the female’s back, while in 1 percent of the cases the male mounted in a reversed head-to-tail position and therefore did not make genital contact. In African jacanas, only about one in four sexual solicitations by the female result in the male actually mounting her.107 In some species, completion of the sexual act is prevented because of interference from other animals, who actively harass males and females while they are copulating. This is typical of many primates, but has also been reported in some birds such as King Penguins, Kittiwakes, and Sage Grouse.108

In a number of animals, it appears that male and female anatomy are not ideally suited to heterosexual interactions. The female Elephant’s vaginal opening, for example, is much farther forward on her belly than in other mammals. Although the male’s penis has a special shape and muscles that allow it to reach the female’s genitals, he still often experiences considerable difficulty in achieving penetration and may end up ejaculating on her anus or otherwise outside her body. Moreover, it is not true that male and female genitals always fit together like a “lock and key”: in many species the structural “compatibility” of the sex organs is less than perfect. In addition, the female’s internal reproductive tract in most animals is—in the words of several zoologists—a tortuous, obstacle-ridden pathway that is “remarkably hostile to sperm.” Its structure, chemical composition, and immune response to semen are actually designed to prevent most sperm from ever achieving fertilization, in part to protect the female from possible infection (sperm are, after all, “foreign” bodies) and in part to allow her to control paternity. 109 Males and females may be anatomically incompatible in other respects as well. Biologists studying Musk-oxen have observed that the male’s build—a deep chest with short legs, and most of his considerable weight concentrated in the front half of his body—is decidedly ill-suited to mounting and clasping the female, and studies have shown that males are able to successfully mount females less than a third of the time.110 In many other species of hoofed mammals and seals where there is a significant size difference between the sexes, females often fall or are crushed under the weight of the male during copulation and may suffer serious (even lethal) injuries.

Sometimes outright hostility erupts between males and females, including chasing and harassment, as well as actual aggression, violence, and injury (inflicted by males on females and, less commonly, by females on males). Attacks can be as brutal as they are commonplace. Female Savanna (Olive) Baboons, for instance, are liable to be attacked almost daily by males without provocation, and each female is severely wounded about once a year; injuries are sometimes fatal. Sexual coercion (i.e., punishment or intimidation by males of “uncooperative” females) as well as outright rape also occur in a wide variety of animals, occasionally involving “gangs” of males that attack and forcibly mate with females.111 Heterosexual rape is especially prevalent among birds such as ducks and gulls, but also occurs in mammals such as primates (e.g., Orang-utans, Rhesus Macaques), hoofed mammals (e.g., Bighorn Sheep), and marine mammals (Right Whales, and numerous seal species). In birds that form pair-bonds, rape usually involves mating attempts on females other than the male’s partner, but forced copulation within the pair-bond is not unknown, occurring, for example, in Silver Gulls, Lesser Scaup Ducks, and several other duck species.

Throughout the animal kingdom, heterosexual mating can be a dangerous and even lethal undertaking for females. Male Sea Otters often bite females on the nose during aquatic copulations, sometimes resulting in drowning or fatal infections; swarms of a dozen or more woodfrogs often try to mate with the same female, occasionally killing her in the process; female sharks of several species are routinely and severely bitten on the back during heterosexual courtship; while male mink may puncture the base of the female’s skull and brain with their teeth during mating. 112 These are just a few examples of how heterosexual mating is often a destructive, rather than a procreative, act.

|

|

|

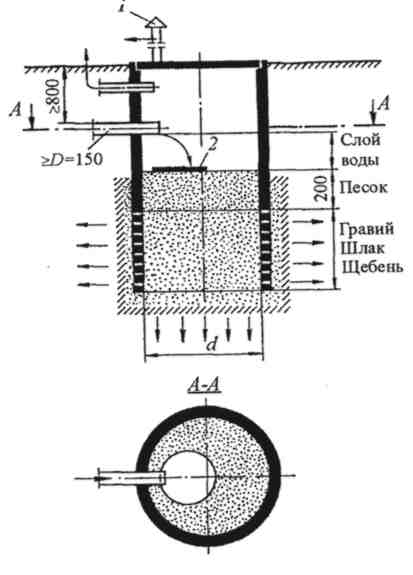

Индивидуальные очистные сооружения: К классу индивидуальных очистных сооружений относят сооружения, пропускная способность которых...

Организация стока поверхностных вод: Наибольшее количество влаги на земном шаре испаряется с поверхности морей и океанов (88‰)...

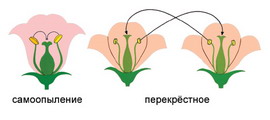

Семя – орган полового размножения и расселения растений: наружи у семян имеется плотный покров – кожура...

Механическое удерживание земляных масс: Механическое удерживание земляных масс на склоне обеспечивают контрфорсными сооружениями различных конструкций...

© cyberpedia.su 2017-2025 - Не является автором материалов. Исключительное право сохранено за автором текста.

Если вы не хотите, чтобы данный материал был у нас на сайте, перейдите по ссылке: Нарушение авторских прав. Мы поможем в написании вашей работы!