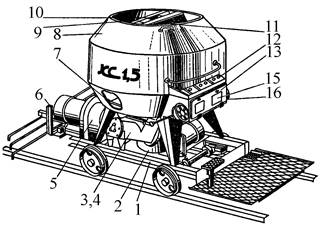

Кормораздатчик мобильный электрифицированный: схема и процесс работы устройства...

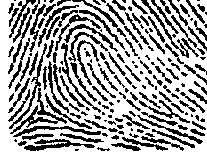

Наброски и зарисовки растений, плодов, цветов: Освоить конструктивное построение структуры дерева через зарисовки отдельных деревьев, группы деревьев...

Кормораздатчик мобильный электрифицированный: схема и процесс работы устройства...

Наброски и зарисовки растений, плодов, цветов: Освоить конструктивное построение структуры дерева через зарисовки отдельных деревьев, группы деревьев...

Топ:

Организация стока поверхностных вод: Наибольшее количество влаги на земном шаре испаряется с поверхности морей и океанов...

Оснащения врачебно-сестринской бригады.

История развития методов оптимизации: теорема Куна-Таккера, метод Лагранжа, роль выпуклости в оптимизации...

Интересное:

Как мы говорим и как мы слушаем: общение можно сравнить с огромным зонтиком, под которым скрыто все...

Влияние предпринимательской среды на эффективное функционирование предприятия: Предпринимательская среда – это совокупность внешних и внутренних факторов, оказывающих влияние на функционирование фирмы...

Инженерная защита территорий, зданий и сооружений от опасных геологических процессов: Изучение оползневых явлений, оценка устойчивости склонов и проектирование противооползневых сооружений — актуальнейшие задачи, стоящие перед отечественными...

Дисциплины:

|

из

5.00

|

Заказать работу |

Содержание книги

Поиск на нашем сайте

|

|

|

|

Although the first reports of homosexual behavior among primates were published >75 years ago, virtually every major introductory text in primatology fails to even mention its existence.

—primatologist PAUL L. VASEY, 199560

In the 1890s, Oscar Wilde’s lover, Lord Alfred Douglas, characterized homosexuality as “the Love that dare not speak its name,” referring to the silence and stigma surrounding disclosure of homosexual interests and discussion of same-sex activities. 61 An analogue to this silencing and stigmatization exists in the pages of zoology journals, monographs, and textbooks, and in the wider scientific discourse. Discussion of homosexual activity in animals has frequently been stifled or eliminated, and a number of examples can only be considered active suppression of information on the subject. When several comprehensive reference works devoted to every conceivable aspect of an animal’s biology and behavior are published, including chapters by scientists who originally observed homosexuality in the species, and yet consistently no mention is made of that homosexual behavior, one has to wonder about the “objectivity” of these scientific endeavors.

At one extreme, there are cases of apparently deliberate removal of information. In 1979, a report on Killer Whale behavior was issued by the Moclips Cetological Society, a nonprofit scientific organization devoted to whale study. Sexual activity between males—classified explicitly as “homosexuality” in the report—was discussed at some length, concluding with the statement, “Homosexual behavior has been observed in many animals including cetaceans, canids, and primates, and, in some cases, it has significance for social order.” A year later, when this report was published as a government document for the U.S. Marine Mammal Commission, all mention of homosexuality was eliminated even though the remainder of the report was intact.62 At the other extreme are cases where homosexuality is discussed but is buried in unpublished dissertations, obscure technical reports, foreign-language journals, or in articles whose titles give no clue as to their content. For example, the earliest reports of same-sex courtship and mounting in wild Musk-oxen appeared in an unpublished master’s thesis at the University of Alaska and a (published) report for the Canadian Wildlife Service. Consequently, a study on homosexual activity in captive Musk-oxen conducted more than 20 years after the initial discovery fails to mention any occurrence of this behavior in the wild. Similarly, the first reports of Walrus homosexual activity, complete with photographs, were published in an article with the rather opaque title of “Walrus Ethology I: The Social Role of Tusks and Applications of Multidimensional Scaling,” while all records of homosexual behavior in Harbor Seals are contained in unpublished reports and conference proceedings that are only available at a handful of libraries in the world. This perhaps explains why virtually every subsequent discussion of homosexuality in animals omits any mention of these two species.63

Between these extremes are numerous examples where homosexuality is “overlooked” or fails to gain mention. Describing itself as “the culmination of years of intensive research and writing by more than 70 authors”—all experts on the species—the massive book White-tailed Deer: Ecology and Management (1984) presents in minute detail every imaginable aspect of this animal’s biology and behavior, no matter how obscure or rare. There’s even room in the book’s nearly 900 pages for lengthy discussion of “abnormal” and pathological phenomena (a category in which homosexual activity is often placed). Although the chapter on behavior was coauthored by the scientist who originally described homosexual mounting in White-tailed Deer, there is no mention anywhere in the book of this particular behavior. Nor is there discussion of the transgendered deer found in Texas, even though a whole chapter is devoted to this regional population. A decade later, the same scenario was repeated when another volume of the same scope and on the same species was put out by the same publishers. Similarly, a standard scientific source book, The Gray Whale, Eschrichtius robustus (1984), omits any reference to homosexuality in this species even though it includes a chapter by the first biologist to record same-sex activity in Gray Whales.64 Several comprehensive reference volumes on woodpeckers fail to mention homosexual copulations in Black-rumped Flamebacks, even though no other (hetero)sexual behavior has ever been observed in this species. This omission cannot be due to the putative rarity or “insignificance” of such behavior, since one book does mention another behavior that has only ever been observed once in wild woodpeckers—bathing.65 Other in-depth surveys of individual species follow suit, eliminating any mention of homosexuality even when they make direct use of other information from the very sources that describe same-sex activity.66

Because of the omission and inaccessibility of information on animal homosexuality in the scientific literature, many zoologists are themselves unaware of the full extent of the phenomenon. One of the most unfortunate consequences of this is that misinformation (and absence of information) about the subject is widely disseminated and perpetuated from one source to the next. On discovering homosexual activity in a particular species they are studying firsthand—and being unable to find more than a handful of comparable examples in a cursory literature search—many zoologists acquire the mistaken impression that their observations of this behavior are somehow unique or unusual. At that point they may issue blanket statements to the effect that homosexual activity is rare or previously unreported in the form or species they are observing. Such statements are then often repeated by other biologists and become definitive pronouncements on the subject. As recently as 1993, for example, a scientist reporting on Hooded Warblers could claim that male homosexual pairs had not previously been seen in wild birds—when, in fact, such pairs were documented more than a quarter century earlier in Antbirds, Orange-fronted Parakeets, Golden Plovers, and Mallard Ducks, and thereafter in Black Swans, Scottish Crossbills, Black-billed Magpies, and Pied Kingfishers, among others.67 Scientists studying same-sex pairs of Black-headed Gulls in captivity asserted in 1985 that this behavior had yet to be seen in this species in the wild—apparently unaware of a description of a male homosexual pair in wild Black-headed Gulls published in a Russian zoology journal just a year earlier. And researchers who discovered same-sex matings in Adélie and Humboldt Penguins and in Kestrels stated that they did not know of any comparable phenomena in other species of penguins or birds of prey, when in fact homosexual activity in King Penguins, Gentoo Penguins, and Griffon Vultures had previously been reported in the literature.68

Sadly, omission and misinformation on the subject of animal homosexuality have ramifications far beyond the individual scientific articles in which they occur. Reference works such as those mentioned above are frequently consulted by researchers in other fields, and they are also the source of much of the information on animal behavior that is presented to the general public. As the quote at the beginning of this subsection indicates, the cycle is also perpetuated through each new generation of scientists as the textbooks they use (or the professors who instruct them) continue to offer inaccurate or incomplete information on the subject (when they aren’t completely silent on the topic). It is no surprise, then, that many scientists—and, by extension, most nonscientists—continue to harbor the erroneous impression that homosexuality does not exist in animals or is at best an isolated and anomalous phenomenon. When erasure and silence surround the subject among zoologists, misinformation and prejudice readily fill in the gaps—both in the scientific community and beyond.

To conclude this examination of homophobic attitudes in the scientific establishment, one simple observation can be made: given the considerable obstacles encountered in the recording, analysis, and discussion of the subject, it is remarkable that any descriptions of animal homosexuality make it to the pages of scientific journals and monographs (or to a wider audience). A great deal of progress is being made, and the situation today is certainly improved over that of even a decade ago. Moreover, none of this discourse would even be possible without the invaluable work of zoologists and wildlife biologists who study animals firsthand and report their findings—however flawed that study and reporting may be at times. Nevertheless, the examples of animal homosexuality currently contained in the zoological literature represent only the tip of the iceberg. Many more remain to be discovered, recorded, and granted the scientific attention that has so repeatedly been denied them in the past.

Anything but Sex

As we have seen, one way that zoologists have tried to avoid classifying same-sex activity as “homosexuality” is by using terminology and behavioral categories that deny it is sexual activity at all. This approach also extends to the interpretations, explanations, and “functions” attributed to same-sex behavior, even when it involves the most overt and explicit of activities. Astounding as it sounds, a number of scientists have actually argued that when a female Bonobo wraps her legs around another female, rubbing her own clitoris against her partner’s while emitting screams of enjoyment, this is actually “greeting” behavior, or “appeasement” behavior, or “reassurance” behavior, or “reconciliation” behavior, or “tension-regulation” behavior, or “social bonding” behavior, or “food exchange” behavior—almost anything, it seems, besides pleasurable sexual behavior. 69 Similar “interpretations” have been proposed for many other species (involving both males and females), allowing scientists to claim that these animals do not really engage in “genuine” (i.e., purely sexual) homosexual activity. But what heterosexual activity is ever “purely” sexual?

Two female Bonobos participating in “GG (genito-genital) rubbing”

Most biologists are not as candid as Valerius Geist, who, in Mountain Sheep and Man in the Northern Wilds, readily admits to his discomfort and homophobia in trying to “explain” homosexuality in Bighorn Rams as “aggressive” or “dominance” behavior:

I still cringe at the memory of seeing old D-ram mount S-ram repeatedly …. True to form, and incapable of absorbing this realization at once, I called these actions of the rams aggressosexual behavior, for to state that the males had evolved a homosexual society was emotionally beyond me. To conceive of those magnificent beasts as “queers”—Oh God! I argued for two years that, in [wild mountain] sheep, aggressive and sexual behavior could not be separated …. I never published that drivel and am glad of it …. Eventually I called the spade a spade and admitted that rams lived in essentially a homosexual society.70

This section will examine a number of nonsexual interpretations, including attempts to classify homosexuality as dominance or aggressive behavior, as a form of play, as a social interaction that relieves group tension, and as a greeting activity. In many cases, these “explanations” are not so much genuine attempts to understand the phenomenon as they are ways of denying its existence in the first place. Often these interpretations are simply incompatible with the facts, especially where “dominance” is involved. Furthermore, while in many instances animal homosexuality does have components of all these (nonsexual) activity types, this does not cancel its sexual aspects. As Paul L. Vasey observes, “Just because a behavior which is sexual in form serves some social role or function doesn’t mean it cannot be simultaneously sexual.”71 Indeed, both animal and human heterosexualities also share aspects of these nonsexual functions without losing their classification as “sexual” activities.

The Dominant Paradigm

In many animal societies, individuals can be ranked with respect to each other on the basis of a number of factors—aggression, access to food or heterosexual mating opportunities, age and/or size, and so on. The resulting hierarchy of individuals and their interaction within this system is often subsumed under the term dominance. Many scientists have suggested that mounting and other sexual behaviors between animals of the same sex are not in fact sexual behavior at all, but rather express dominance relations between the two individuals. The usual interpretation is that the “dominant” partner mounts the “subordinate” one and thereby asserts or solidifies his or her ranking relative to that individual. This “explanation” of homosexual behavior is firmly entrenched within the scientific establishment: one of the earliest statements of this position is a 1914 description of same-sex mounting in Rhesus Macaques, and since then dominance factors have regularly been invoked in discussions of animal homosexuality.72 Most scientists have appealed to dominance as an explanation for animal homosexuality only in relation to the particular species (or at most, animal subgrouping) that they are studying—and sometimes only for one sex within that species—without regard for a broader range of considerations. Once the full panoply of animal types, behaviors, and forms of social organization is taken into account, however, it becomes quite clear that dominance has little, if any, explanatory power. While dominance may be relevant in a few specific cases, it cannot account for the full range of homosexual interactions found throughout the natural world. Moreover, even in particular instances where dominance seems to be important, mitigating factors usually render its influence suspect, if not irrelevant.

At the most basic level, dominance is neither a sufficient nor a necessary condition for the occurrence of homosexual behavior in a species. Just because an animal has a dominance-based or ranked form of social organization does not mean that it exhibits homosexuality, and just because homosexual behavior occurs in a species does not mean that it has a dominance hierarchy. For example, many animals with dominance hierarchies have never been reported to engage in homosexual mounting. Dominance systems are found in “the vast majority of mammal species forming groups with any degree of social complexity”—most primates, seals, hoofed mammals, kangaroos, and rodents, for instance—yet only a fraction of these participate in same-sex mounting. Specific examples of birds with dominance hierarchies but no reported homosexuality include curlews, silvereyes, Harris’s sparrows, European jays, black-capped chickadees, marabou storks, white-crowned sparrows, and Steller’s jays.73 Conversely, homosexuality is found in many animals that do not have a dominance hierarchy or in which the relative ranking of individuals plays only a minor role in their social system: for example, some populations of Gorillas, Savanna (Olive) Baboons, Bottlenose Dolphins, Mountain and Plains Zebras, Musk-oxen, Koalas, Buff-breasted Sandpipers, and Tree Swallows.74

Often, the relevance of dominance to homosexuality contrasts sharply in two closely related species: Pukeko have a well-defined dominance hierarchy that some scientists believe impacts on the birds’ homosexual behavior, yet in the related Tasmanian Native Hen, same-sex mounting occurs in the absence of a dominance hierarchy. Male homosexual mounting has been claimed to correlate with dominance in Cattle Egrets, yet in Little Blue Herons this connection is expressly denied. And the white-browed sparrow weaver (and several other species of weaver birds) has an almost identical social organization and dominance system as the Gray-capped Social Weaver, yet mounting between males is only found in the latter species.75 Not only cross-species but also cross-gender comparisons are relevant here. A particularly good example of the problematic relationship between dominance and same-sex activity becomes apparent when one looks at males and females within the same species. In many animals both sexes have their own dominance hierarchies, yet homosexuality occurs in only one sex—male but not female Wolves, for example, and female but not male Spotted Hyenas. A corollary to this is that in some species, only one sex exhibits a stable dominance hierarchy, yet homosexuality occurs among both males and females. In Squirrel Monkeys, for example, female interactions are not consistently organized around a dominance or rank system, yet same-sex mounting and genital displays are not limited to males. In Bottlenose Dolphins, stable dominance hierarchies (if they exist at all) are more prominent among females, yet homosexual activity occurs in both sexes.76 Finally, homosexual mounting sometimes occurs between animals of different species. Although cross-species dominance relations have been documented (e.g., in birds), in the majority of the cases involving homosexual activity there is no well-established hierarchical relationship between the participating animals of different species.77 Clearly, then, dominance cannot be the only factor involved in the occurrence of homosexuality in a given species.

Even in animals where there is a clear dominance hierarchy, same-sex mounting is often not correlated with an individual’s rank, and it rarely follows the idealized scenario of “dominant mounts subordinate, always and without exception.” In many species, there is simply no correlation between rank and mounting behavior, since subordinate animals frequently mount dominant ones. In Rhesus Macaques, for example, 36 percent of mounts between males are by subordinates on dominants, while 42 percent of all female Japanese Macaque homosexual mounts go “against” the hierarchy, as do 43 percent of mounts between male Common Chimpanzees. 78 Both dominant-subordinate and subordinate-dominant mounting occur in Bonobos, Lion-tailed Macaques, Squirrel Monkeys, Gelada Baboons, and Ruffs, among others, while mounting of older, larger, and/or higher-ranking animals by younger, smaller, and/or subordinate individuals has also been reported for numerous species: Common Marmosets, Australian and New Zealand Sea Lions, Walruses, Bottlenose Dolphins, White-tailed Deer, Mule Deer, Père David’s Deer, Wapiti, Moose, Mountain Goats, Red Foxes, Spotted Hyenas, Whiptail Wallabies, Rufous Rat Kangaroos, Mocó, Préa, Guianan Cock-of-the-Rock, Emus, and Acorn Woodpeckers. Oftentimes, while a large proportion of mounts may seem to follow the dominance hierarchy in a particular species, mounting by subordinates on dominants also takes place in the same species. This is true for Hanuman Langurs, Bonnet Macaques, Musk-oxen, Bighorn and Thinhorn Sheep, Cattle Egrets, and Sociable Weavers.79

The precise opposite of the “standard” dominance-based system of mounting is often found as well: mountings by subordinates on dominants occur more frequently than the reverse in many species. In Crested Black Macaques, for example, 60—95 percent of mounts are subordinate on dominant, while nearly two-thirds of Bison male homosexual mounts are by subordinates on dominants. To complicate things further, this is often combined with a gender difference in the relationship between mounting and dominance, with female mounts “following” the hierarchy and male mounts going “against” it. For instance, in Pig-tailed Macaques mounting between females is usually by a dominant individual on a subordinate one, but more than three-quarters of mounts between males are just the opposite. Similarly, in both Red Deer and Pukeko, females tend to mount lower-ranking animals while males tend to mount higher-ranking ones. There are often individual or geographic differences as well: in some consortships between female Japanese Macaques, all mounting is done by the lower-ranking individual on the higher-ranking partner, while in some populations of Bighorn Sheep, mounting of dominant rams by subordinates is much more prevalent than in other populations.80 Furthermore, homosexual mounting in many species is reciprocal, which means that partners exchange positions—mounter becomes mountee, and vice versa—either in the same mounting session or in alternation over longer periods of time. This behavior, which is found in at least 30 different species, is potent evidence of the irrelevance of dominance for homosexual interactions, since mounting should only occur unidirectionally if it strictly followed the rank of the participating individuals.81 Finally, in some species mounting can also occur between individuals of the same or close ranks—for example, in Common Chimpanzees, White-faced Capuchins, Musk-oxen, Blackbucks, Cavies, and Gray-capped Social Weavers.82

In a dominance-based view of homosexual mounting, it is often assumed that the animal being mounted is somehow a less willing participant in the interaction, “submitting” to the will of the more dominant individual, who thereby asserts his or her “superiority.” In fact, in more than 30 species the mounted animal actually initiates the interaction, “presenting” its hindquarters to the other individual as an invitation to mount, sometimes even actively facilitating anal penetration (among males) or other aspects of the interaction. Where the presenting animal is subordinate, this could be interpreted as simply a reinforcement of the dominance system, but in a number of species it is actually the more dominant individual who presents and actively encourages the lower-ranking animal to mount.83 In addition, dominance “explanations” often ignore the clear differences between consensual and nonconsensual mounts (or rapes), as well as evidence for sexual arousal and even enjoyment on the part of mounted animals.84

The relationship between sexuality and dominance is complex and multifaceted, differing greatly from the frequent simplistic equating of homosexual mounting with nonsexual rank-based or aggressive behavior. In many species a gradation or continuum exists between sexual mounts and dominance mounts, with one type “blending” into the other so that any distinction between the two is essentially arbitrary. Thus, same-sex mounting can have an unmistakable sexual component even when it still follows a dominance pattern. Among Hanuman Langurs, for example, usually only dominant females mount subordinate ones, yet so inextricably linked are signs of sexual excitement with this behavior that scientists have concluded, “It seems virtually impossible to separate ‘sexual mounting’ from ‘dominance mounting.’ … Sexual arousal and dominance are obviously not mutually exclusive in langur females, since mounting between females is related to both dominance and sexuality.”85 At the other end of the spectrum, in some species a sharp distinction does in fact exist between two types of mounting, both of which occur between same-sex partners: a nonsexual form associated with dominance and/or aggression, and a clearly sexual form that occurs in other contexts (often within a homosexual pair-bond or consortship). This is true for female Japanese Macaques, Rhesus Macaques, and Black-winged Stilts, and male Greylag Geese, among others.86

Finally, in some animals dominance and mounting are entirely separate, with social rank being expressed through obviously nonsexual activities. For example, male Walrus dominance interactions involve fighting and tusk displays that usually occur during the breeding season and often involve younger animals. Male homosexual mounting is not associated with either of these activities and usually takes place in the nonbreeding season among males of all age groups (a similar pattern is also seen in Gray Seals). Oystercatchers use a special ritualized “piping display” (neck arched, bill pointed downward, accompanied by shrill piping notes) to negotiate their dominance interactions, while same-sex mounting and courtship occur in other contexts.87 Dominance in many other animals is expressed through fighting and aggressive encounters, access to food or feeding frequency, body size or age, physical displacement (causing another individual to move off through posture, threats, staring, or other activities), access to heterosexual mating opportunities, or a combination of these or other factors, and specifically does not involve mounting or the other homosexual interactions that occur in these species. Savanna (Yellow) Baboons, (female) Hamadryas Baboons, Bottlenose Dolphins, Killer Whales, Caribou, Blackbucks, Wolves, Bush Dogs, Spotted Hyenas, Grizzly Bears, Black Bears, Red-necked Wallabies, Canada Geese, Scottish Crossbills, Black-billed Magpies, Jackdaws, Acorn Woodpeckers, and Galahs are all species in which this is the case.88

Another limitation in looking at homosexual interactions from the perspective of dominance is that only mounting behavior lends itself to such an interpretation. A whole host of other homosexual activities do not fit neatly into the dominance paradigm—either because, by their very nature, they are reciprocal activities, or because neither participant can be assigned a clearly “dominant” or “subordinate” status on the basis of what “position” it assumes during the activity. For example, mutual genital rubbing—in which two animals rub their genitals on each other without any penetration—often occurs with neither participant “mounting” the other. Gibbon and Bonobo males frequently engage in this activity when hanging suspended from a branch, facing each other in a more “egalitarian” position. In aquatic animals such as Gray Whales, West Indian Manatees, Bottlenose Dolphins, and Botos, males rub their penises together or stimulate each other while rolling and clasping one another in constantly shifting, fluid body positions that defy any categorization as “mounter” or “mountee.” Reciprocal rump rubbing and genital stimulation—found in Chimpanzees and some Macaques—also renders meaningless a dominance-based view of homosexual interactions. When two males or two females back toward each other and rub their anal and genital regions together, sometimes also manually stimulating each other’s genitals—which one is “dominating” the other? Or when a male Vampire Bat grooms his partner, licking his genitals while simultaneously masturbating himself, which one is behaving “submissively”? By the same token, Crested Black Macaque females have a unique form of mutual masturbation in which they stand side by side facing in opposite directions and stimulate each other’s clitoris—again, because of the pure reciprocity, it makes little sense to interpret this behavior as expressing some sort of hierarchical relationship between the partners.

Genital rubbing, masturbation of one’s partner, oral sex, anal stimulation other than mounting, and sexual grooming occur among same-sexed individuals in more than 70 species—yet virtually all of these forms of sexual expression fall outside the realm of clear-cut dominance relationships.89 These more mutual, reciprocal, or dominance-ambiguous sexual activities are commonly found alongside homosexual mounting behavior in the same species—but the former are typically ignored when a dominance analysis is advocated.90 Ironically, another entire sphere of homosexual activity eludes a dominance interpretation—any same-sex interaction that is not overtly sexual. Courtship, affectionate, pair-bonding, and parenting behaviors that do not involve genital contact or direct sexual arousal—yet still occur between same-sex partners—are routinely omitted from any discussion of the relevance of dominance to the expression of homosexuality.91 The exclusion of nonsexual behaviors such as these from dominance considerations contrasts, paradoxically, with the way that mounting behavior itself is ultimately rendered nonsexual by its inclusion under the category of dominance.

Male Stumptail Macaques manually stimulating each other’s genitals. Mutual or reciprocal sexual behaviors such as this are good examples of homosexual activity that is not “dominance” oriented.

A final indictment of a dominance analysis is that the purported ranking of individuals based on their mounting or other sexual behavior often fails to correspond with other measures of dominance in the species. Male Giraffes, for example, have a well-defined dominance hierarchy in which the rank of an individual is determined by his age, size, and ability to displace other males with specific postures and stares. Homosexual mounting and “necking” behavior is usually claimed to be associated with dominance, yet a detailed study of the relationship between these activities and an individual’s social standing according to other measures revealed no connection whatsoever. Mounting position also fails to reflect an individual’s rank as measured by aggressive encounters (e.g., threat and attack behavior) and other criteria in male Crested Black Macaques, male Stumptail Macaques, and female Pig-tailed Macaques. In only about half of all male homosexual mounts among Savanna (Olive) Baboons is there a correlation between dominance status, as determined in aggressive or playful interactions, and the role of an animal as mounter or mountee. In male Squirrel Monkeys, dominance status affects an individual’s access to food, heterosexual mating opportunities, and the nature of his interactions with other males, yet the rank of males as evidenced by their participation in homosexual genital displays does not correspond in any straightforward way to these other criteria. Among male Red Squirrels, there is no simple relationship between aggressiveness and same-sex mounting: the most aggressive individual in one study population indeed mounted other males the most frequently, yet he was also the recipient of mounts by other males the most often, while the least aggressive male was hardly ever mounted by any other males. This is also true for Spinifex Hopping Mice, in which males typically mount males who are more aggressive than themselves. Similarly, although male Bison fairly consistently express dominance through displays such as chin-raising and head-to-head pushing, these behaviors do not offer a reliable predictor of which will mount the other. Although some mounts between male Pukeko appear to be correlated with the dominance status of the participants (as determined by their feeding behavior, age, size, and other factors), there is no consistent relationship between these measures of dominance and another important indicator of rank—a male’s access to heterosexual copulations (or the number of offspring he fathers). Finally, dominance relations in Sociable Weavers are not always uniform across different measures either: one male, for example, was “dominant” to another according to their mounting behavior, yet “subordinate” to him according to their pecking and threat interactions.92

In fact, multiple nonsexual measures of dominance often fail to correspond even among themselves, and this has led some scientists to suggest that the entire concept of dominance needs to be seriously reexamined, if not abandoned altogether. While it may have some relevance for some behaviors in some species, dominance (or rank) is not a fixed or monolithic determinant of animal behavior. Its interaction with other factors is complex and context-dependent, and it should not be accorded the status of a preeminent form of social organization that it has traditionally been granted.93 Primatologist Linda Fedigan advocates a more sophisticated approach to the role of dominance in animal behavior, eloquently summarized in the following statement. Although her comments are specifically about primates, they are relevant for other species as well:

We often oversimplify the phenomena categorized together as dominance, as well as overestimating the importance of physical coercion in day-to-day primate life …. An additional focus on alliances based on kinship, friendship, consortship, and roles, and on social power revealed in phenomena such as leadership, attention-structure, social facilitation, and inhibition, may help us to better understand the dynamics of primate social interaction. Also it may help us to place competition and cooperation among social primates in proper perspective as intertwined rather than opposing forces, and female as well as male primates in their proper perspective as playing major roles in primate “politics” through their participation in alliance systems.94

Considering the wide range of evidence against a dominance analysis of animal homosexuality—as well as a number of explicit statements by zoologists questioning or entirely discounting dominance as a factor in same-sex activities95—it is surprising that this “explanation” keeps reappearing in the scientific literature whenever homosexual behavior is discussed. Yet reappear it does, even in several studies published in the 1990s. As recently as 1995, in fact, dominance was invoked in a discussion of mounting between male Zebras, and this explanation still has enough currency that scientists felt compelled to refute it in a 1994 account of homosexual copulation in Tree Swallows. In looking through the many examples of the way that this “explanation” has been used, it becomes apparent that the relevance of dominance is often asserted without any supporting evidence, then cited and re-cited in subsequent studies to create a chain of misconstrual, as it were, extending across many decades of scientific investigation. Again and again, early characterizations of homosexual activity as dominance behavior—often hastily proposed on the initial (and unexpected) discovery of this behavior in a species—have been refuted by later, more careful investigations of the phenomenon.96 Yet frequently only the earlier studies are cited by researchers, perpetuating the myth that this is a valid characterization of the behavior. For example, in a 1974 report that described same-sex mounting in Whiptail Wallabies, a zoologist referred to dominance interpretations of Rhesus Macaque homosexuality even though more recent studies had invalidated—or at the very least, called into question—such an analysis for this species.97

At times, the very word dominance itself becomes simply code for “homosexual mounting,” repeated mantralike until it finally loses what little meaning it had to begin with. “Dominance” interpretations have in fact been applied to same-sex mounting regardless of how overtly sexual it is. The relatively “perfunctory” mounts between female Tree Kangaroos or male Bonnet Macaques, as well as interactions involving direct clitoral stimulation to orgasm between female Rhesus Macaques, and full anal penetration and ejaculation in Giraffes, have all been categorized as nonsexual “dominance” activities at one time or another. Even though many scientists have gone on record against a dominance interpretation—thereby challenging the stronghold of this analytic framework—information that contradicts a dominance analysis is sometimes troublesomely discounted or omitted from studies. For example, in several reports on dominance in Bighorn rams, same-sex mounting and courtship activities (as well as certain aggressive interactions) were deliberately excluded from statistical calculations because they frequently involved “subordinates” acting as “dominants,” i.e., they did not conform to the dominance hierarchy. One scientist even classified some instances of same-sex mounting in Crested Black Macaques as “dysfunctional” because they failed to reflect the dominance system or exhibit any other “useful” properties.98

Nor is this merely a question of relevance to scientists, or simply a matter of esoteric academic interpretation. The assertions made by zoologists about the “functions” of homosexual behavior are often picked up and repeated, unsubstantiated, in popular works on animals, becoming part of our “common knowledge” of these creatures. In a detailed survey of primate homosexuality published in 1995, zoologist and anthropologist Paul L. Vasey finally and definitively put the dominance interpretation of homosexuality in its proper perspective, stating that “while dominance is probably an important component of some primate homosexual behavior, it can only partially account for these complex interactions.”99 We can only hope that his colleagues—and ultimately, those who convey the wonders of animal behavior to all of us—will take these words to heart once and for all.

|

|

|

История развития хранилищ для нефти: Первые склады нефти появились в XVII веке. Они представляли собой землянные ямы-амбара глубиной 4…5 м...

Папиллярные узоры пальцев рук - маркер спортивных способностей: дерматоглифические признаки формируются на 3-5 месяце беременности, не изменяются в течение жизни...

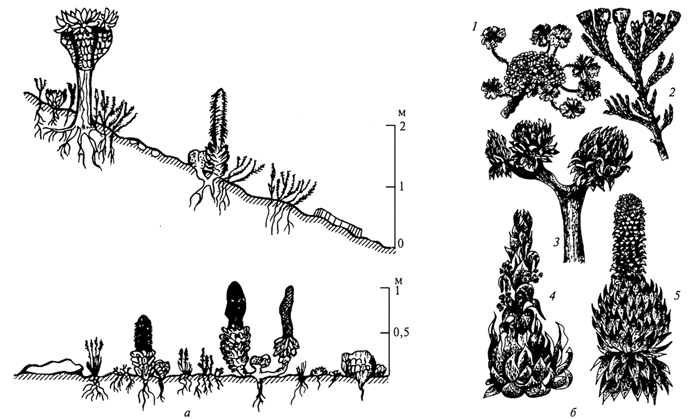

Адаптации растений и животных к жизни в горах: Большое значение для жизни организмов в горах имеют степень расчленения, крутизна и экспозиционные различия склонов...

Своеобразие русской архитектуры: Основной материал – дерево – быстрота постройки, но недолговечность и необходимость деления...

© cyberpedia.su 2017-2025 - Не является автором материалов. Исключительное право сохранено за автором текста.

Если вы не хотите, чтобы данный материал был у нас на сайте, перейдите по ссылке: Нарушение авторских прав. Мы поможем в написании вашей работы!