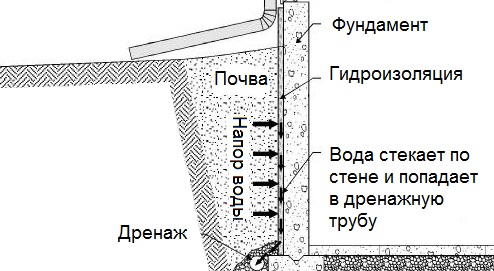

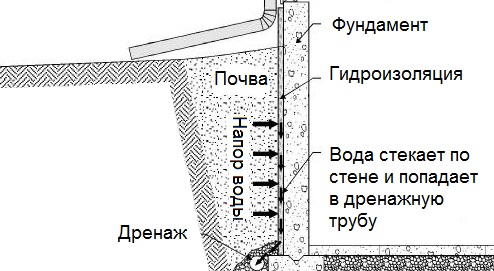

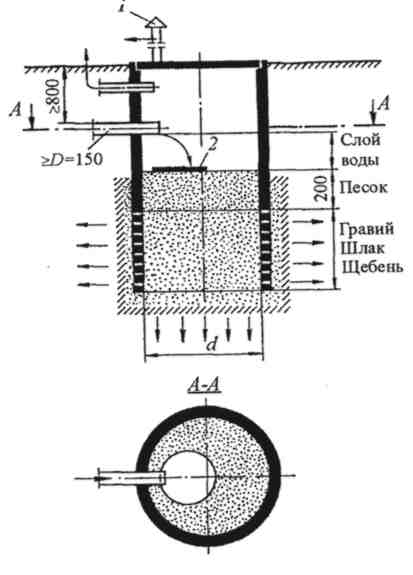

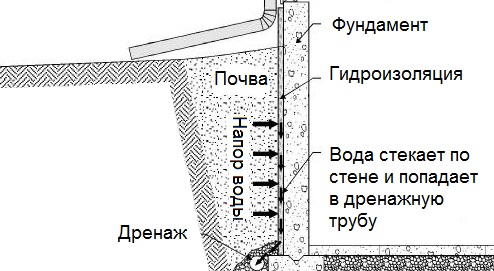

Общие условия выбора системы дренажа: Система дренажа выбирается в зависимости от характера защищаемого...

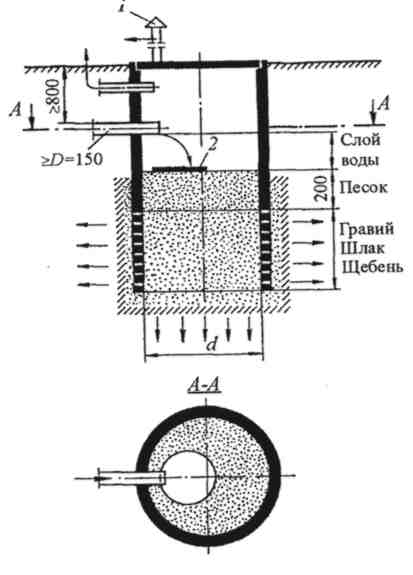

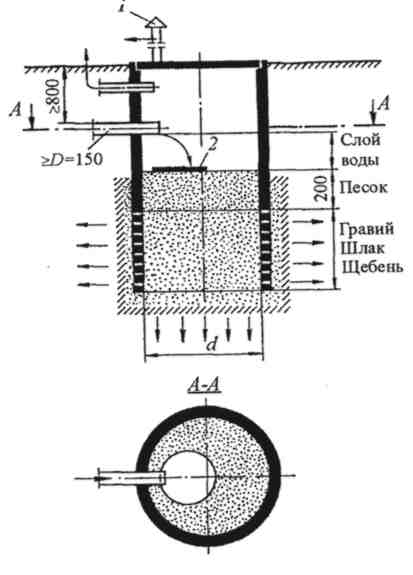

Индивидуальные очистные сооружения: К классу индивидуальных очистных сооружений относят сооружения, пропускная способность которых...

Общие условия выбора системы дренажа: Система дренажа выбирается в зависимости от характера защищаемого...

Индивидуальные очистные сооружения: К классу индивидуальных очистных сооружений относят сооружения, пропускная способность которых...

Топ:

История развития методов оптимизации: теорема Куна-Таккера, метод Лагранжа, роль выпуклости в оптимизации...

Особенности труда и отдыха в условиях низких температур: К работам при низких температурах на открытом воздухе и в не отапливаемых помещениях допускаются лица не моложе 18 лет, прошедшие...

Интересное:

Распространение рака на другие отдаленные от желудка органы: Характерных симптомов рака желудка не существует. Выраженные симптомы появляются, когда опухоль...

Мероприятия для защиты от морозного пучения грунтов: Инженерная защита от морозного (криогенного) пучения грунтов необходима для легких малоэтажных зданий и других сооружений...

Финансовый рынок и его значение в управлении денежными потоками на современном этапе: любому предприятию для расширения производства и увеличения прибыли нужны...

Дисциплины:

|

из

5.00

|

Заказать работу |

Содержание книги

Поиск на нашем сайте

|

|

|

|

Same-sex pairs in many species (especially birds) raise young together. Not only are they competent parents, homosexual pairs sometimes actually exceed heterosexual ones in the number of eggs they lay, the size of their nests, or the skill and extent of their parenting. How are such animals able to have offspring in the first place if they are in homosexual associations? Many different strategies are used, including several in which one or both partners are the biological parent(s) of the young they raise together. The most common parenting arrangement of this type is found in lesbian pairs of several Gull, Tern, and Goose species: one or both female partners copulate with a male to fertilize her eggs. No bonding or long-term association develops between the female and the male (who is essentially a “sperm donor” to the homosexual pair), and the youngsters are then jointly raised by both females without any assistance from a male parent. Because female birds can lay eggs regardless of whether they are fertilized, however, each partner in a lesbian pair usually contributes a full clutch of eggs to their nest even if she hasn’t mated with a male. As a result, female homosexual pairs often lay what are called supernormal clutches, that is, double the number of eggs usually found in nests of heterosexual pairs.10

Sometimes two female animals who already have offspring join forces, bonding together and raising their young as a same-sex family unit (among mammals, female coparents may even suckle each other’s young): this occurs in Grizzly Bears, Red Foxes, Warthogs, Dwarf Cavies, Lesser Scaup Ducks, and Sage Grouse. Notably, heterosexual pairs do not occur in these species, and most offspring are otherwise raised by single females.11 In some species, a nonbreeding animal bonds with a (single) breeding animal and helps parent its young: this occurs in Squirrel Monkeys, Northern Elephant Seals, Jackdaws (where a widowed female with young may pair with a single female), and Greater Rheas (where one male may help another incubate his eggs and then raise the young together). In most such joint parenting arrangements (as opposed to homosexual mated pairs), there is not necessarily any overt courtship or sexual activity between the bonded coparents, although in some species (e.g., Squirrel Monkeys, Northern Elephant Seals, Emus, Sage Grouse), homosexual activity does occur in contexts other than between coparents. Still other birds (e.g., Greylag Geese, Common Gulls, Oystercatchers) may form bisexual parenting trios, mating with the opposite-sexed partner(s) in their association while maintaining homosexual and heterosexual bonds simultaneously, with all three birds then raising the resulting offspring together. A variation on this arrangement in Black Swans involves a sort of “surrogate motherhood”: established male homosexual pairs sometimes associate temporarily with a female, mating with her to father their own offspring. Once the eggs are laid, however, they chase her away and raise the cygnets on their own as a homosexual couple.

In a number of cases, homosexual pairs raise young without being the biological parents of the offspring they care for. Some same-sex pairs adopt young: two female Northern Elephant Seals occasionally adopt and coparent an orphaned pup, while male Hooded Warblers and Black-headed Gulls may adopt eggs or entire nests that have been abandoned by females, and pairs of male Cheetahs occasionally look after lost cubs. Sometimes female birds “donate” eggs to homosexual couples through a process known as parasitism: in many birds, females lay eggs in nests other than their own, leaving the parenting duties to the “host” couple. This occurs both within the same species, and (more commonly) across species, and usually involves heterosexual hosts. Male pairs of Hooded Warblers, however, sometimes receive eggs from Brown-headed Cowbirds (and possibly also from females of their own species) in this way; within-species parasitism may also provide eggs for male pairs of Black-headed Gulls and female pairs in Roseate and Caspian Terns. The opposite situation is thought to occur in Ring-billed Gulls: researchers believe that some homosexually paired females actually lay eggs in nests belonging to heterosexual pairs. Finally, some birds in same-sex pairs take over or “kidnap” nests from heterosexual pairs (e.g., in Black Swans, Flamingos) or occasionally “steal” individual eggs (e.g., in Caspian and Roseate Terns, Black-headed Gulls); homosexual pairs in captivity also raise foster young provided to them.

A homosexual pair of male Flamingos tending their foster chick

In a detailed study of parental behavior by female pairs of Ring-billed Gulls, scientists found no significant differences in quality of care provided by homosexual as opposed to heterosexual parents. They concluded that there was not anything that male Ring-billed Gull parents provided that two females could not offer equally well.12 This case is not exceptional: homosexual parents are generally as good at parenting as heterosexual ones. Examples of same-sex pairs successfully raising young have been documented in at least 20 species, and in a few cases, homosexual couples actually appear to have an advantage over heterosexual ones.13 Pairs of male Black Swans, for example, are often able to acquire the largest and best-quality territories for raising young because of their combined strength. Such fathers—dubbed “formidable” adversaries by one scientist—consequently tend to be more successful at raising offspring than most heterosexual pairs.14 And in many species in which single parenting is the rule (because there is no heterosexual pair-bonding), same-sex pairs provide a unique opportunity for young to be raised by two parents (e.g., Squirrel Monkeys, Grizzly Bears, Lesser Scaup Ducks). Moreover, in some Gulls, female pairs are consigned (for a variety of reasons) to less than optimal territories, yet they still successfully raise young: in many cases they compensate by investing more parental effort—and are more dutiful in caring for their chicks—than male-female pairs.15 There are exceptions, of course: some female pairs of Gulls, for instance, tend to lay smaller eggs and raise fewer chicks (although this is also true of heterosexual trios attending supernormal clutches), while same-sex parents in Jackdaws, Canada Geese, and Oystercatchers may experience parenting difficulties such as egg breakage or nonsynchronization of incubation duties. By and large, though, same-sex couples are competent and occasionally even superior parents.

Birds in homosexual pairs often build a nest together. Usually they construct a single nest the way most heterosexual pairs do, but other variations also occur: female Common Gulls and Jackdaws sometimes make “twin” or “joint” nests containing two cups in the same bowl, while male Greater Rheas and female Canada Geese may use “double” nests consisting of two adjacent or touching nests. Female Mute Swans occasionally construct two separate nests in which both birds lay eggs. Nests belonging to male couples in some species (e.g., Flamingos and Great Cormorants) are often impressive structures, exceeding the size of heterosexual nests because both males contribute equally to their construction (in heterosexual pairs of these species, usually only one sex builds the nest, or males and females make unequal contributions). Many same-sex pairs construct nests regardless of whether they lay fertile eggs. Male pairs of Mute Swans, Flamingos, Black-crowned Night Herons, and Great Cormorants, for example, usually build nests even though they never acquire eggs, and the male “parents” may even sit on the nests as if they contained eggs, while female pairs frequently build nests in which they lay supernormal clutches that are entirely infertile. Same-sex parents often share incubation duties, either taking turns sitting on their nest (the most common arrangement), or else incubating simultaneously on a single nest (female Red-backed Shrikes, male Emus) or side by side on a twin or double nest (female Jackdaws, male Greater Rheas).

In addition to parenting by homosexual couples, some animals raise young in alternative family arrangements, usually a group of several males or females living together. Gorilla babies, for example, grow up in mixed-sex, polygamous groups where their mothers may have lesbian interactions with each other, while Pukeko and Acorn Woodpeckers live and raise their young in communal breeding groups where many, if not all, group members engage in courtship and sexual activities with one another (both same-sex and opposite-sex). In such situations, individuals that engage in homosexual courtship or copulation activities may either reproduce directly because they also mate heterosexually (Pukeko), or they may assist members of their group in raising young without reproducing themselves (Acorn Woodpeckers).16 Other alternative family constellations include bisexual trios (mentioned above), homosexual trios (as in Grizzly Bears, Dwarf Cavies, Lesser Scaup Ducks, and Ring-billed Gulls) where three mothers jointly parent their offspring, and even quartets, in which four animals of the same (Grizzlies) or both sexes (Greylag Geese) are bonded to each other and all raise their young together.17

Finally, some animals that have homosexual interactions are “single parents.” Many female mammals, for example, that court or mate with other females also mate heterosexually and raise the resulting young on their own or in female-only groups (as is typical for exclusively heterosexual females in the same species as well). This is especially prevalent among mammals with polygamous or promiscuous heterosexual mating systems, such as Kob and Pronghorn antelopes and Northern Fur Seals (where males, and sometimes females, usually mate with more than one partner). Males in many polygamous species are often bisexual as well, fathering offspring in addition to courting or mating with other males; typically, however, they do not actively parent their offspring regardless of whether they are bisexual or exclusively heterosexual.18

What’s Good for the Goose …: Comparisons of Male and Female Homosexuality

Is homosexuality more characteristic of male animals or female animals? And does it assume different forms in the two sexes—or, to paraphrase a popular saying, is the behavior of the “goose” essentially similar to that of the “gander”? As it so happens, homosexuality in three species of Geese—Canada, Snow, and Greylag—exemplifies some of the major patterns of male and female homosexuality and the range of variation found throughout the rest of the animal world. In Canada Geese, both males and females participate in the same basic type of homosexual activity, forming same-sex pairs and engaging in some courtship activities. Within these same-sex bonds, however, there are gender differences in some less common behaviors: sexual activity is more characteristic of females (especially if they are part of a bisexual trio), as is nest-building and parenting activity. There are also differences in the frequency of participation of the two sexes: although same-sex pairs are relatively common, accounting for more than 10 percent of pairs in some populations, a greater proportion of the male population participates in same-sex pairing. In contrast, homosexual activity in Snow Geese is vastly different in males than in females, although it is relatively infrequent in both sexes. Females form long-lasting pair-bonds with other females in which sexual activity is not necessarily very prominent, although parenting activity is: both partners lay eggs in a joint nest and raise their young together (they fertilize their eggs by mating with males). Ganders, on the other hand, limit their homosexual activity to same-sex mounting of other males during heterosexual group rape attempts and do not form same-sex pairs (although interspecies gander pairs with Canada Geese sometimes do occur). Finally, in Greylag Geese homosexual activity is found exclusively in males, who form gander pairs that engage in a variety of courtship, sexual, pair-bonding, and parenting activities.

When we look at the full range of species and behaviors, we find that male homosexuality is slightly more prevalent, overall, than female homosexuality, although the two are fairly close. Same-sex activity (of all forms) occurs in male mammals and birds in about 80 percent of the species in which homosexuality has been observed, and between females in just over 55 percent of these (the figures add up to more than 100 percent because both male and female homosexuality are found in some species). It must also be kept in mind that the prevalence of female homosexuality may actually be greater than these figures indicate, but has simply not been documented as systematically owing to the general male bias of many biological studies.19 There is also variation between different animal subgroupings: in carnivores, marsupials, waterfowl, and shorebirds, for example, male and female homosexuality are almost equally common (in terms of the number of species in which each is found), while in marine mammals and perching birds male homosexuality is more prevalent. And in many species same-sex activity occurs only among males (e.g., Boto, a freshwater dolphin) or only among females (e.g., Puku, an African antelope).

The frequency of same-sex behavior in males versus females can also be assessed within a given species, and once again, many different patterns are found: in Rhesus Macaques, Hamadryas and Gelada Baboons, and Tasmanian Native Hens, for example, 80—90 percent of all same-sex mounting is between males, while homosexual activity is also more prevalent among male Gray-headed Flying Foxes.20 In other species, female homosexual activity assumes prominence: more than 70 percent of same-sex copulations in Pukeko are between females, and 70—80 percent of homosexual activity in Bonobos is lesbian. Females account for almost two-thirds of same-sex behaviors in Stumptail Macaques and Red Deer, while homosexual activity is also more typical of females in Red-necked Wallabies and Northern Quolls.21 In some species, however, male homosexuality is so predominant that same-sex activity in females is often missed by scientific observers or rarely mentioned (e.g., Giraffes, Blackbuck, Bighorn Sheep), while the reverse is true in other species (e.g., Hanuman Langurs, Herring Gulls, Silver Gulls). In contrast, Pig-tailed Macaque same-sex mounting, Galah pair-bonds, and Pronghorn homosexual interactions are fairly equally distributed between the two sexes (although actual same-sex mounting is more common in male Pronghorns).22

As with the species of Geese mentioned above, gender differences are also apparent in various behavior types. Of those mammal and bird species in which some form of homosexual behavior occurs, each of the activities of courtship, affectionate, sexual, or pair-bonding are generally more prevalent in male animals. They occur among males in 75—95 percent of the species in which they are found, while among females these activities occur in 50—70 percent of the species (again, however, the possible gender bias of the studies these figures are based on must be kept in mind). The one exception is same-sex parenting, which is performed by females in more than 80 percent of the species where this behavior occurs, but by males in just over half of the species that have some form of such parenting. Of course, not all these forms of same-sex interaction always co-occur in the same species, and animals sometimes differ as to which activities males as opposed to females of the same species tend to participate in (as in the Geese). In Silver and Herring Gulls, for example, females form same-sex pairs that undertake parenting duties while males engage in homosexual mounting; in Cheetahs and Lions, both sexes engage in sexual activity, but males in each species also develop same-sex pair-bonds while female Cheetahs participate in same-sex courtship activities. In Ruffs, males engage in sexual, courtship, and (occasional) pairing activity with each other, while Reeves (the name for females of this sandpiper species) participate primarily in sexual activity with one another.

Within each of the categories of courtship, sexual, pairing, and parenting behaviors, further gender distinctions can be drawn. Consider various types of sexual behavior. Mounting as a same-sex activity is ubiquitous and occurs fairly regularly in both males and females (although there are exceptions—in African Elephants, for example, sexual activity between males assumes the form of mounting while female same-sex interactions consist of mutual masturbation). Oral sex (which includes activities as diverse as fellatio, cunnilingus, genital nuzzling and sniffing, and beak-genital propulsion) is about equally prevalent in both sexes. Group sexual activity is more common in males (only occurring among females in 6 species, including Bonobos and Sage Grouse), as are interactions between adults and adolescents (only occurring among females in 9 species, including Hanuman Langurs, Japanese Macaques, Ring-billed Gulls, and Jackdaws, but among males in more than 70 species). Although penetration is also more typical of male homosexual interactions, there are notable exceptions (e.g., Bonobos, Orang-utans, and Dolphins, as mentioned previously). Gender differences sometimes also manifest themselves in the minutiae of various sexual acts. Same-sex mounting in Gorillas, for instance, is performed in both face-to-face and front-to-back positions, but the two sexes differ in the frequency with which these two positions are used: females prefer the face-to-face position, adopting it in the majority of their sexual interactions, while males use it less often, in only about 17 percent of their homosexual mounting episodes.23 In contrast, the frequency of full genital contact during homosexual copulations is nearly identical for both sexes of Pukeko: females achieve cloacal contact in about 23 percent of their same-sex mounts while males do so in about 25 percent of theirs (in comparison, genital contact occurs in a third to half of all heterosexual mounts). Among Flamingos, though, genital contact is more characteristic of copulations between females than between males.24

Or consider pair-bonding and parenting. Stable, long-lasting pair-bonds are generally not more characteristic of females (contrary to what one might initially expect); mated pairs or partnerships are almost equally common in both sexes (in terms of number of species in which homosexual pair-bonding occurs), while same-sex companionships are more prevalent between males. Likewise, long-term pair-bonds are just as likely to be found between males as females, while nonmonogamy and divorce occur in male and female couples in roughly equal numbers of species. Nor are male couples less successful parents: male coparents or partners are not overrepresented among the few species in which same-sex parents occasionally experience parenting difficulties. One area where a gender difference in same-sex parenting does manifest itself is in the way that homosexual pairs “acquire” offspring. Particularly among birds, female couples can raise their own offspring by simply having one or both partners mate with males without interrupting their homosexual pair-bond. This option is not as widely available for male couples, who usually father their own offspring by forming a longer-lasting (prior or simultaneous) association with a female (as in Black Swans, Greylag Geese, and Greater Rheas).

Japanese Macaques offer a particularly compelling example of the multiple ways that homosexual activity can differ between males and females. Although homosexual mounting occurs in both sexes in this species, males and females differ in the specific details of their sexual interactions. Homosexual mounts are usually initiated by the mounter between males but by the mountee between females, make use of a wider variety of mounting positions between females, are accompanied by a unique vocalization only between males, and involve pelvic thrusting and multiple mounts more often between females than between males.25 The two sexes also differ in their partner selection and pair-bonding activities: females generally form strongly bonded consortships and have fewer partners than males, while the latter tend to interact sexually with more individuals and develop less intense bonds (although some do have “preferred” male partners). Finally, there is a seasonal difference in male as opposed to female same-sex interactions: homosexual mounting is more common outside the breeding season in males but during the breeding season in females, while same-sex bonds in females, but not males, may extend into yearlong associations that transcend the breeding season.

Whether we’re talking about ganders and geese or Ruffs and Reeves, whether it’s Botos and Bonobos or Pukus and Pukeko, male and female homosexuality can be either surprisingly similar to each other or decidedly distinctive from one another. In any case, a complex intersection of factors is involved in the expression of homosexuality in each gender. As with other aspects of animal homosexuality, preconceived ideas about how males and females act must be reassessed and refined when considering the full range of animal behaviors. In some species such as Silver Gulls, male and female homosexualities conform to stereotypes commonly held about similar human behaviors: females form stable, long-lasting lesbian pair-bonds and raise families while males participate in promiscuous homosexual activity. In other species these gender stereotypes are turned completely on their heads, as in Black Swans, where only males form long-term same-sex couples and raise offspring, and Sage Grouse, where only females engage in group “orgies” of homosexual activity.26 And in the majority of cases, male and female homosexualities present their own unique blends of behaviors and characteristics that defy any simplistic categorization—such as Bonobos, where sexual penetration occurs in female rather than male same-sex activity, where sexual interactions between adults and adolescents are a prominent feature of female interactions, and where males do not form strongly bonded relationships with each other the way females do, but engage in less homosexual activity overall and more affectionate activity such as openmouthed kissing. Once again, the diversity of animal homosexuality reveals itself down to the very last detail of expression.

|

|

|

Индивидуальные очистные сооружения: К классу индивидуальных очистных сооружений относят сооружения, пропускная способность которых...

Общие условия выбора системы дренажа: Система дренажа выбирается в зависимости от характера защищаемого...

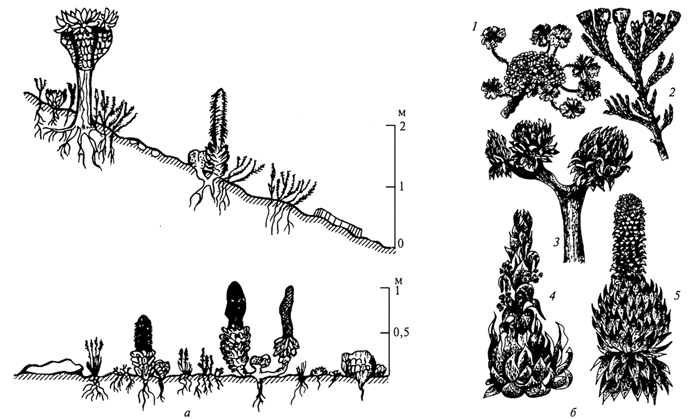

Адаптации растений и животных к жизни в горах: Большое значение для жизни организмов в горах имеют степень расчленения, крутизна и экспозиционные различия склонов...

Таксономические единицы (категории) растений: Каждая система классификации состоит из определённых соподчиненных друг другу...

© cyberpedia.su 2017-2025 - Не является автором материалов. Исключительное право сохранено за автором текста.

Если вы не хотите, чтобы данный материал был у нас на сайте, перейдите по ссылке: Нарушение авторских прав. Мы поможем в написании вашей работы!