The traditional view of the animal kingdom—what one might call the Noah’s ark view—is that biology revolves around two sexes, male and female, with one of each to a pair. The range of genders and sexualities actually found in the animal world, however, is considerably richer than this. Animals with females that become males, animals with no males at all, animals that are both male and female simultaneously, animals where males resemble females, animals where females court other females and males court other males—Noah’s ark was never quite like this! Homosexuality represents but one of a wide variety of alternative sexualities and genders. Many people are familiar with transvestism or transsexuality only in humans, yet similar phenomena are also found in the animal kingdom. Although this book focuses primarily on homosexuality, it is helpful to compare this with related phenomena that are often confused with homosexuality, and to discuss some specific examples of each.

Many animals live without two distinct genders, or with multiple genders. In hermaphrodite species, for instance, all individuals are both male and female simultaneously, and hence there are not really two separate sexes; in parthenogenetic species, all individuals are female and they reproduce by virgin birth. A number of other phenomena in the animal kingdom—for which we will use the cover term transgender —involve the crossing or traversing of existing gender categories: for example, transvestism (imitating the opposite sex, either behaviorally, visually, or chemically), transsexuality (physically becoming the opposite sex), and intersexuality (combining physical characteristics of both sexes).46

Early descriptions of animal homosexuality often mistakenly called the animals “hermaphrodites,” since any “transgression” of gender categories (such as sexual behavior) was usually equated with physical gender-mixing. True hermaphroditism, however, involves animals that have both male and female reproductive organs at the same time. This phenomenon is found in many invertebrate organisms, such as slugs and worms, as well as in a number of fish species (for example, lantern fishes and some species of hamlets and deep-sea fishes). Some hermaphrodites can fertilize themselves, but mating in many hermaphroditic species involves two individuals having sex with each other in order to mutually exchange both eggs and sperm.47 Since both such individuals have identical biologies, i.e., are of the same (dual) sex, technically such behavior could be classified as homosexual. However, such activity differs from actual homosexuality because it occurs in a species that does not have two separate sexes, and because it typically does result in procreation. In species that do have two distinct sexes, there are other types of hermaphroditism or intersexuality, in which individuals combine various physical features of both sexes. These differ from species-wide, true hermaphroditism because such animals are not able to reproduce as both males and females simultaneously, and they usually comprise only a fraction of the otherwise nonhermaphroditic population. Further examples of this type of transgender will be discussed in chapter 6.

Virgin birth, or parthenogenesis, is not just the stuff of religions: it is actually found in over a thousand species worldwide and is a “natural” form of cloning. Each member of a parthenogenetic species is biologically female (that is, capable of producing eggs). Rather than requiring sperm to fertilize these eggs, however, she simply makes an exact copy of her own genetic code. Virgin birth is found in a number of fishes, lizards, insects, and other invertebrates. In most parthenogenetic species, individuals do not have sex with each other, but in some species, such as the Amazon Molly and Whiptail Lizards, females actually court and mate with one another, even though no eggs (or sperm) are exchanged in such encounters.

Whereas homosexuality and bisexuality involve activity within the same gender, hermaphroditism and parthenogenesis involve courtship and sexual behavior without genders (at least, without one class of individuals that are male and another class that are female). In contrast, transvestism and transsexuality are a kind of “crossing over” from one gender or sexual category to another, or the combining of elements from each category. In transvestism, individuals of one biological sex take on the characteristics of the other sex, either behaviorally or physically, without actually changing their own sex. In transsexuality, individuals actually become the opposite sex, so that a male turns into a female or vice versa (where male and female are used strictly in the reproductive sense to refer to animals that produce sperm or eggs, respectively).

Transvestism is widespread in the animal kingdom and takes a variety of forms.48 Both male-to-female and female-to-male transvestism occur: some female African swallowtail butterflies, for example, resemble males in their wing coloration and patterning, while in some species of squid, males imitate female arm postures during aggressive encounters.49 Physical transvestism can involve almost total physical resemblance between males and females, or mimicry of only certain primary or secondary sexual characteristics. For instance, in several species of North American perching birds, young males resemble adult females in their plumage—making them distinct from both adult males and juvenile females. In some birds, such as the painted bunting, the resemblance between adult females and juvenile males is nearly total, while in others, younger males are more intermediate between adult males and females in appearance.50 Several species of hoofed mammals show a different type of physical transvestism: female mimicry of the horns or tusks found in males.51 Female Chinese water deer, for example, grow special tufts of hairs on their jaws that resemble the tusks of the male, while female Musk-oxen have a patch of hair on their foreheads that mimics the males’ horn shield. Physical transvestism can also be chemical or scent-based: some male Common Garter Snakes, for example, produce a scent that resembles the female pheromone, causing males to mistake them for females and attempt to court and mate with them.

In behavioral transvestism, an animal of one sex acts in a way that is characteristic of members of the opposite sex of that species—often fooling other members of their own species. For example, males of several species of terns imitate female food-begging gestures to steal food from other males. Behavioral transvestism does not mean animals behaving in ways that are thought to be “typically” male or female in other species. In sea horses and pipefishes, for instance, the male bears and gives birth to the young. Even though these are activities usually thought to be “female,” this is not a genuine case of transvestism because it is part of the regular behavior patterns and biology of the species (i.e., it is true for all males and no females). Female sea horses never bear young, nor are they fooled into thinking that males aren’t male because they do bear young. The same goes for initiation of courtship: in some species the female is more aggressive in initiating courtship and copulation (e.g., in greater painted-snipes), yet this could only be considered “transvestism” with reference to other species in which females do not initiate such activity.52

The question of transvestism is an important one for animal homosexuality because these two phenomena have often been confused. Many scientists have labeled all examples of animal homosexuality male or female “mimicry” since they consider any same-sex behavior to be nothing more than imitation of the opposite sex. True, many animals, when courting and mating homosexually, employ behavior patterns that the opposite sex also employs. In most cases, however, this simply involves making use of the available behavioral repertoire of the species rather than being an attempt to mimic the opposite sex. Moreover, the resemblance to “heterosexual” patterns is often partial at best, while in some species entirely distinct courtship and copulation patterns are used for homosexual activity.53

A good example of the difference between behavioral transvestism and homosexuality is in the Bighorn Sheep. In this species, males and females lead almost entirely separate lives: they live in sex-segregated herds for most of the year and come together for only a few short months during the breeding season. Among males, homosexual mounting is common, while females do not generally permit themselves to be mounted by males except when they are in heat (estrus). A small percentage of males, however, are behavioral transvestites: they remain in the female herds year-round and also mimic female behavior patterns. Significantly, such males also generally refuse to allow other males to mount them, just the way females do. Thus, among Bighorn Sheep, being mounted by a male is a typically “masculine” activity, while refusal of such mounting is a typically “feminine” behavior. Males who mimic females specifically avoid homosexuality. This is the exact opposite of the stereotypical view of male homosexuality, which is often considered to be a case of males “imitating” females. It is also a striking reminder of how important it is not to be misled by our preconceptions about human homosexuality when looking at animals.54

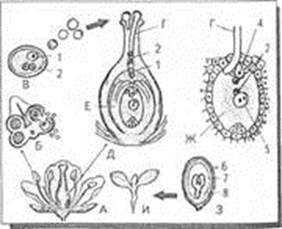

Transsexuality or sex change is a routine aspect of many animals’ lives, especially in invertebrates: shrimp, oysters, and sow bugs, for example, all undergo complete reversals of their sex at some stage in their lives.55 It is among coral-reef fish, however, that the most remarkable examples of transsexuality are found. More than 50 species of parrot fishes, wrasses, groupers, angelfishes, and other species are transsexual. In all such cases, the reproductive organs of the fish undergo a complete reversal. What were once fully functional ovaries, for example, become fully functional testes, and the formerly female fish is able to mate and reproduce as a male.56

The types of sex change that are found, the number and fluidity of genders, and the overall social organization of these species are so complex that a detailed terminology has been developed by scientists to describe all the variations. In some species, females turn into males (this is called protogynous sex change), while in others males become females (called protandrous sex change). In some fish, sex change is maturational; that is, it happens automatically to all individuals when they reach a certain age or size or else occurs spontaneously at different times for each individual. In other species, sex change appears to be triggered by factors in the social environment of the fish, such as the size, sex, or number of neighboring fish. In female-to-male fish species, many different gender profiles are found. In some cases, all fish are born female, and males result only from sex change (such a system is called monandric). In other cases, both genetic males (born male) and sex-changed males are found (this arrangement is called diandric). In these fishes, genetic males are sometimes referred to as primary males while sex-changed males are called secondary males. Often these two types of males differ in their coloration, behavior, and social organization so that transsexual males form a distinct and clearly visible “gender” in the population.

Homosexuality as a “masculine” activity: a male Bighorn ram mounts another ram. Males who mimic females in this species (behavioral transvestites) do not generally permit other males to mount them, unlike nontransvestite rams.

Things get even more complicated in some species. Among secondary males, some change sex before they mature as females (prematurational secondary males), while others change sex only after they live part of their adult life as females (post-maturational secondary males). Many species also have two distinct color phases: fish often begin life with a dull color and drab patterning, then change into the more brilliant hues typically associated with tropical fish as they get older. Which individuals change color, when they change, and their gender at the time of the color change can yield further variations. Many species of parrot fishes, for example, have multiple “genders” or categories of individuals based on these distinctions. In fact, in some families of fishes, transsexuality is so much the norm that biologists have coined a term to refer to those “unusual” species that don’t change sex— gonochoristic animals are those with two distinct sexes in which males always remain male and females always remain female.

As an example of how elaborate transsexuality can become in coral-reef fish, consider the striped parrot fish, a medium-sized species native to Caribbean and Atlantic waters from Bermuda to Brazil (the name refers to the fact that its teeth are fused together like a parrot’s beak).57 Striped parrot fish, like many sex-changing fishes, have both males that were born as males and males that were born as females. In fact, more than half of all males in this species used to be females. Moreover, all female striped parrot fish eventually change their sex, becoming male once they reach a certain size; the sex change can take as little as ten days to be completed. Sex-changed males have fully functional testes that used to be fully functional ovaries when the fish was female; they are able to mate and fertilize eggs the same way that genetic males do. Striped parrot fish have one of the most complex polygendered societies in the animal kingdom. There are five distinct genders, distinguished by biological sex, genetic origin, and color phase. Biological sex refers to whether the fish has ovaries (= female) or testes (= male). Genetic origin refers to whether the fish was born that sex or has changed from another sex (= transsexual). Color phase refers to the two types of coloration that striped parrot fish exhibit: initial-phase fish (so named because all fish start out with this coloration) are a drabber brown or bluish gray, while terminal-phase fish are a brilliant blue-green and orange. These three categories intersect to create the following five genders (percentages refer to what proportion of the total population, at any given time, belongs to each gender): (1) genetic females: born female, each of these initial-phase fish will eventually become a male and change color (45 percent); (2) initial-phase transsexual males: born female, these fish become male before they change into their bright colors and are fairly rare (1 percent); (3) terminal-phase transsexual males: born female, these fish become male at the same time they changed color, usually at a later age than genetic males (27 percent); (4) initial-phase genetic males: born male, most of these will change color as they get older (but won’t change sex) (14 percent); and (5) terminal-phase genetic males: born male, these fish start out as initial-phase males and change color (but not sex) at a younger age than transsexual males (13 percent).

Along with its numerous genders and fluid changes between them, striped parrot fish society is characterized by a number of intricate systems of social organization and mating patterns, each found in a particular geographic area. One system, known as group spawning or explosive breeding assemblages, is common in Jamaican striped parrot fish. Large groups of up to 20 initial-phase males and females gather to spawn together, swimming in dramatic formations that rapidly change direction. Often, terminal-phase males try to disrupt this mating activity. Another system is found in the waters off Panama and is known as haremic because the basic breeding group consists of one terminal-phase male and several females. These individuals are known as territorials since they live in permanent locations that they defend against intruders. Other fish in the same area, however, associate with each other in different kinds of groups: “stationaries” are celibate (nonbreeding) fish in both initial and terminal phases, while “foragers” gather together to feed in large groups of up to 500 fish. Some of these foraging groups are composed of females and initial-phase genetic males, while others are made up only of terminal-phase males; half of all the females, and all the males, in such groups are nonbreeders. Finally, striped parrot fish in the waters off Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands associate together in “leks,” clusters of small, temporary territories that both initial-phase and terminal-phase males defend and use to attract females for spawning.

Further variations in transsexuality are found in other species. The paketi or spotty, a New Zealand fish, combines transsexuality with transvestism (some females become males before changing color, thus “masquerading” as females), while the humbug damselfish combines transsexuality with same-sex pairings and associations. An even more complex gender system, involving hermaphroditism, transsexuality, transvestism, and apparent homosexual activities, exists in the lantern bass and other fishes. In addition to nontranssexual males and females, some individuals are hermaphrodites (both male and female at the same time) and others are secondary (transsexual) males, while in a few cases individuals exhibit courtship and mating patterns typical of the opposite sex (directed toward individuals of the same sex). All female Red Sea anemonefish start out as males; once they change sex, however, they become dominant to males and tend “harems” of up to nine males, all but one of whom are nonbreeders. Finally, although most transsexual fishes are one-way sex changers, in a few species sex change actually occurs in both directions. In the coral goby, for instance, some individuals go from male to female, others from female to male, and some even undergo multiple sequential changes, “back and forth” from male to female to male, or female to male to female.58

As these examples show, not only are transgendered and genderless biologies a fact of life for many animals, they have developed into incredibly sophisticated and complex systems of social organization and behavioral patterning in many species. For those of us used to thinking in terms of two unchanging and wholly separate sexes, this is extraordinary news indeed. Likewise, animal homosexuality itself is a rich and multifaceted phenomenon that is at least as complex and varied as heterosexuality Animals of the same sex court each other with an assortment of special—and in some cases, unique—behavior patterns. They are both affectionate and sexual toward one another, utilizing multiple forms of touch and sexual technique, ranging from kissing and grooming to cunnilingus and anal intercourse. And they form pair-bonds of several different types and durations and even raise young in an assortment of same-sex family configurations. If, as scientist J. B. S. Haldane stated, the natural world is queerer than we can ever know, then it is also true that the lives of “queer” animals are far more diverse than we could ever have imagined. In the next chapter, we’ll take a look at how these different forms of sexual and gender expression in animals compare to similar phenomena in people.

Chapter 2