The Ufaina believe in a vital force called fufaka which is … present in all living beings. This vital force, whose source is the sun, is constantly recycled among plants, animals, men, and the Earth itself …. When a being dies it releases this energy … similarly when a living thing consumes another …. The sun revolves around the cosmos distributing energy to all equally.

—MARTIN VON HILDEBRAND, “An Amazonian

Tribe’s View of Cosmology”120

Solar energy is the source of life’s exuberant development.

—GEORGES BATAILLE, “Laws of General Economy”121

The concept of Biological Exuberance encapsulates a number of converging lines of thought in a wide range of scientific disciplines. In essence, it is a new way of looking at the world—but in a sense, it is not new at all. This “modern” worldview is uncannily similar to the perspectives of indigenous peoples around the globe, whose ancient “cosmologies” often bear striking resemblances to the most sophisticated recent theories of particle physics or deep ecology. Perhaps the most significant aspect of the intersection of chaos science, post-Darwinian evolution, and biodiversity /Gaia theory is its potential to initiate a return to indigenous sources of knowledge.

A number of scientists in each of these “new” scientific disciplines are starting to acknowledge the teachings of aboriginal cultures. Some of the most prominent and respected researchers in biodiversity studies, chaos theory, and the new evolutionary paradigms are waking up to the fact that their innovative ideas are echoed in aboriginal belief systems around the world. For instance, Edward O. Wilson invokes the visionary insights of indigenous Amazonian shamans, as well as the classificatory expertise of native New Guineans, to illustrate the biodiversity and “exuberance of tropical rain-forest life.”122 Pioneering chaos mathematician Ralph Abraham recognizes that ancient and tribal cultures are cut through with “chaotic” patterns, such as the “fractal architecture” of the indigenous peoples of Mali.123 There is even serious discussion among respected scientists of “respiritualizing” our relationship with nature and looking to indigenous cultures for guidance, faced as we are with the global destruction of ecosystems and massive losses in species diversity. 124 Indigenous knowledge of natural history among the Inupiaq (Eskimo) and Koyukon people of Alaska, the O’odham and Yaqui people of the Southwest, and the Fore and various other New Guinean tribes is offered as a model for Western scientists addressing biodiversity issues.125 The indigenous concept of an animal’s “spirit” is embraced by wildlife biologist Douglas Chadwick, who suggests that a view of animals as “beings with languages and elaborate societies of their own” and perhaps even “some shared quality of consciousness” is useful for an integrated scientific understanding of their behavior and role in the ecosystem. Renowned conservation biologists such as Michael E. Soulé and R. Edward Grumbine also point to Native American spirituality—such as the shamanic Bear ceremonialism of many First Nations (including the Bear Mother myth)—as an important part of the solution to our current biodiversity crisis.126

Gaian and post-Darwinian evolutionary theorists such as Peter Bunyard and Edward Goldsmith are also calling for a return to indigenous worldviews as a way of understanding the nonlinear complexities of nature.127 Many of these aboriginal cosmologies, like that of the Amazonian Ufaina people referred to above, involve sophisticated conceptualizations of the flow of “life energy” that parallel contemporary environmental and economic theories, including Bataille’s theory of General Economy. Others are in accordance with some of the basic tenets of chaos and Gaia theory in recognizing the importance of “exceptional,” statistically rare, or apparently paradoxical phenomena. Frank LaPena, a traditional poet and artist of the Wintu tribe as well as a native anthropologist, succinctly captures this perspective, which is simultaneously ancient and modern: “The earth is alive and exists as a series of interconnected systems where contradictions as well as confirmations are valid expressions of wholeness.”128

One of the most powerful symbols of scientists’ newfound willingness to listen to indigenous sources took place at the National Forum on BioDiversity in 1986. Organized by the National Academy of Sciences and held at the Smithsonian Institution, this prestigious conference brought together more than 60 distinguished scholars and scientists from around the world. Their task: to discuss the importance of biodiversity as we approach the twenty-first century. One of the most eagerly anticipated speakers was neither a “scholar” nor a “scientist” in the conventional sense. Native American storyteller Larry Littlebird, a member of the Keres nations of New Mexico, was invited to give an indigenous perspective on the natural world. As the audience sat in hushed attention on the final day of the conference, Littlebird treated the biologists to an enigmatic tale of Lizard, who summons forth rain clouds with a song that most ordinary humans can’t hear.129

Although this unprecedented event is an encouraging sign of a new direction in science, something crucial was missing—the centrality of homosexuality/transgender to indigenous belief systems. How many of the participants at that conference knew that Littlebird’s Pueblo tribe, one of the Keresan peoples, recognizes the sacredness of the two-spirit or kokwimu (man-woman), and honors homosexuality and transgender in both humans and animals? How many of them realized that the Keresan cosmology includes one of the most noteworthy examples of the left-handed, gender-mixing Bear figure?130 Or that the “Lizard” of Littlebird’s story was most likely a Whiptail Lizard, one of several all-female species of the American Southwest that reproduce by parthenogenesis and engage in lesbian copulation?131 How many of them knew that some of the animals mentioned in Littlebird’s closing words, “The deer, eagle, and butterfly dancers are coming …,” exhibit homosexuality and transgender in nature? The answer, unfortunately, is that probably no one in the audience was aware of these connections.

A contemporary Yup‘ik two-spirit, Anguksuar (Richard LaFortune), has drawn attention to the recent convergence of Western scientific thought with indigenous perspectives, and the relevance of notions of gender and sexual fluidity: “Modern science emerged [and] linear flight from disorder led directly to quantum theory. This scrambling toward something orderly and manageable has landed right back in the lap of the Great Mystery: chaos, the unknown, and imagination …. This is a region of the cosmos familiar to many indigenous taxonomies and to which the Western mind is finally returning …. When I read [Fritjof] Capra’s description of the ‘Crisis of Perception’ that appears to be afflicting Western societies, it seemed to make perfect sense that culture, identity, gender, and human sexuality would figure prominently in such a crisis.”132 The fact is that two-spiritedness, homosexuality, bisexuality, and transgender are at the forefront of some of the most significant scientific re-visionings of our time—in which the gap between indigenous and Western perspectives is finally being bridged—yet their contribution is rarely, if ever, acknowledged by Western scientists. When prominent chaos theoreticians, biodiversity experts, and post-Darwinian evolutionists invoke the teachings of tribal peoples, they are usually unaware of the pivotal role played by homosexuality and transgender in these indigenous belief systems, or in the lives of the writers, storytellers, and visionaries who give poetic voice to their scientific concepts.

In the book Evolution Extended, for instance—a recent presentation of innovative scientific and philosophical interpretations of evolutionary theory—the words of Native American poet Joy Harjo are featured prominently as a haunting invocation of life’s interconnectedness.133 Of Muscogee Creek heritage, Harjo has received wide acclaim for her writing, which draws heavily on her indigenous roots and often includes powerful images of the natural world, while also juxtaposing references to specific constructs of Western science such as quantum physics or molecular structures. Harjo is also a “lover of women” whose writing has been anthologized in Gay & Lesbian Poetry in Our Time. She acknowledges lesbian or bisexual authors such as Audre Lorde, June Jordan, Alice Walker, Beth Brant, and Adrienne Rich, as well as the ideas of lesbian-feminism, as primary influences on her work. She has spoken of the importance of eroticism permeating all aspects of life, and she affirms the power of androgyny and the presence of male and female traits in every individual.134 Yet these aspects of Harjo’s life and work are considered incidental or irrelevant to the perspective she brings to the scientific material—not even worth mentioning as one component of her personal vision, let alone a key feature in the bringing together of seemingly disparate worlds that she achieves through her poetry.

“From Wakan Tanka, the Great Spirit, there came a great unifying life force that flowed in and through all things—the flowers of the plains, blowing winds, rocks, trees, birds, animals—and was the same force that had been breathed into the first man. Thus all things were kindred, and were brought together by the same Great Mystery.” So spoke the Oglala (Sioux) chief Luther Standing Bear, whose words grace the pages of Buffalo Nation, a recent book by prominent wildlife biologist Valerius Geist. This vision of the life energy connecting the “buffalo nation” (and all of nature) to the “human nation” underscores the parallel that Geist draws between indigenous and contemporary scientific approaches to wildlife conservation. The sophisticated game-management practices developed by many Native Americans—both traditionally and in their current efforts to resurrect Buffalo herds on their lands—are, according to Geist, at the forefront of recent Bison conservation efforts. Beautifully interwoven through his discussion of this species’ natural history, behavior, and preservation are evocations of the powerful spiritual role played by the Bison in Native American cultures, including descriptions of Mandan Buffalo Dances and the Lakota legend of the White Buffalo Woman. Yet nowhere in this discussion is there any mention of indigenous views on sexual and gender variability in Bison (or humans), let alone of contemporary scientific findings on these topics. Ironically, though, the book still manages to unintentionally present a vivid picture—literally—of Bison homosexuality. In the section on rutting behavior, a photograph of Buffalo mating activity is identified as a bull mounting a female, when in fact it depicts a bull mounting another bull.135 In the end, then, perhaps the animals themselves will have the “final say,” insuring the representation of homosexuality /transgender and its rightful place in both indigenous and Western scientific thinking.

The importance of this missing link cannot be overemphasized. If Western science is to embrace indigenous perspectives—as it should—then it must do so fully, including views on homosexuality/transgender. It cannot pick and choose among aboriginal “beliefs,” salvaging only those that it is most comfortable with while rejecting those that challenge its prejudices. All of us (scientists included) must acknowledge that heeding “aboriginal wisdom” means listening even when—or perhaps, especially when—we aren’t prepared to hear what it has to say about sexual and gender variance. For too long, native views have been sanitized to make them palatable to nonindigenous people. In a world where Native American spirituality is co-opted to sell bottled water—indeed, is sold directly as a “New Age” commodity—it has become something of a cliche to speak of the environmental “balance” and “harmony” of indigenous cultures.136 The reality is that homosexuality and transgender—along with many other beliefs and practices that would probably be considered objectionable by large numbers of people—are usually an integral, if not a central, component of such “balance.” Consider the cosmology of the Bedamini people of New Guinea, which seems to turn conventional ideas about the natural world upside down:

It is believed that homosexual activities promote growth throughout nature … while excessive heterosexual activities lead to decay in nature …. The balance of these forces is dependent on human action …. The Bedamini do not … experience any inconsistency in the cosmic equation of homosexuality with growth and heterosexuality with decay.

—ARVE SØRUM, “Growth and Decay:

Bedamini Notions of Sexuality”137

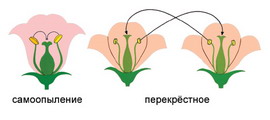

Nor is the association of homosexuality with fecundity unique to this example. As we saw earlier, the renewal and abundance of nature is ensured during Mandan, Yup’ik, and many other cultures’ ceremonies by the symbolic reenactment of animal homosexuality and ritual displays of gender mixing. The Bimin-Kuskusmin human-animal androgynes (who are themselves celibate or postreproductive) are seen as embodiments of fertility, life essence, and earth’s creative powers, while the presence of transgendered and nonreproductive animals is regarded as vital for the productivity of domesticated herds among the Navajo and Chukchi. Rather than being seen as “barren” or counterproductive, then, homosexuality, transgender, and nonbreeding are considered essential for the continuity of life. This is the fundamental “paradox” at the heart of indigenous thinking on alternate genders and sexualities—something that is not, of course, really considered paradoxical at all in these worldviews. It is important that scientists working in chaos theory, biodiversity /Gaia studies, and post-Darwinian evolution acknowledge their genuine affinities with indigenous perspectives. But this process will be complete only when scientists themselves understand this “paradox” and no longer see any inconsistency in the equation of homosexuality/transgender with the vitality of the natural world.

In his study of the 12,000-year-old shamanic worldview of the Tsistsistas (Cheyenne) people and their ancestors, anthropologist Karl Schlesier makes explicit the concordance between ancient and modern perspectives, and the essence of sexual and gender variability that is at its core. According to Schlesier, “The new scientific paradigm initiated by physics and astronomy during the last decades has not only overthrown the rationalistic description that has dominated science for merely four centuries, but is testing concepts regarded as factual in the Tsistsistas world description. The Tsistsistas world description understands power (‘energy’) in the universe … as cosmic power”—a power that controls quantum phenomena and exhibits paradoxical properties, including being both local and nonlocal, causal and noncausal (among others). Central to this understanding is the figure of the gender-mixing or two-spirit shaman, the “halfman-halfwoman” who is a living exemplar of the reconciliation of contraries, a “traveler in the androgynal quest” uniting within him/herself apparently contradictory categories. This conjunction of opposites is seen as a return to the original and timeless state of all matter—the primordial mystery of totality. Homosexuality/transgender is therefore regarded as a hierophany, a manifestation of this sacred oneness and plentitude. “This organic Tsistsistas world description, in which all parts of the universe were interrelated, saw life as wondrous …. This is perhaps the greatest achievement of shamanism since its development: … to interpret the world with all its manifestations as a place of miracles, transformations, and immortality.”138

On the eve of the twenty-first century, human beings have begun to reimagine and reconfigure some of the most fundamental aspects of nature and culture. Stepping into a social and biological landscape that could scarcely have been imagined a few decades ago, homosexual, bisexual, and transgendered people are now offering new paradigms of sexuality and gender for all of us to consider. As part of this process, they are looking simultaneously to indigenous and futuristic sources of inspiration:

In the search for new vocabularies and labels, terms like shapeshifter and morphing have come to be used to refer to gender identity and sexual style presentations and their fluidity. Shapeshifter, originally from Native American culture, was introduced into current popular culture from science fiction, especially a new offshoot of the cyberpunk subgenre made famous by William Gibson and exemplified by the work of Octavia E. Butler, the African-American author of the Xenogenesis series. Butler’s books are inhabited by genetics-manipulating aliens, a polygendered species whose sexuality is multifarious and who are “impelled to metamorphosis,” whose survival in fact depends upon their “morphological change, genetic diversity and adaptations.”

—ZACHARY I. NATAF, “The Future: The Postmodern

Lesbian Body and Transgender Trouble”139

Ironically, one need not look into the future or on “alien worlds” to find appropriate models: shape-shifting and morphing creatures are not merely the stuff of fantasy. The animal world—right now, here on earth—is brimming with countless gender variations and shimmering sexual possibilities: entire lizard species that consist only of females who reproduce by virgin birth and also have sex with each other; or the multigendered society of the Ruff, with four distinct categories of male birds, some of whom court and mate with one another; or female Spotted Hyenas and Bears who copulate and give birth through their “penile” clitorides, and male Greater Rheas who possess “vaginal” phalluses (like the females of their species) and raise young in two-father families; or the vibrant transsexualities of coral reef fish, and the dazzling intersexualities of gynandromorphs and chimeras. In their quest for “postmodern” patterns of gender and sexuality, human beings are simply catching up with the species that have preceded us in evolving sexual and gender diversity—and the aboriginal cultures that have long recognized this. The very melding of indigenous cosmologies and fractal sexualities suggested in the passage above is already well under way—but within the realm of science fact, not fiction.