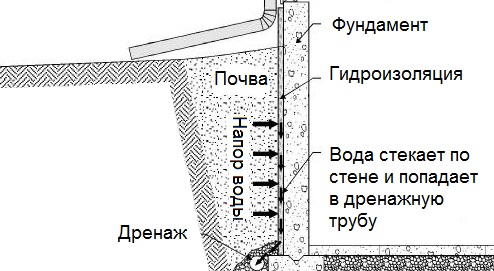

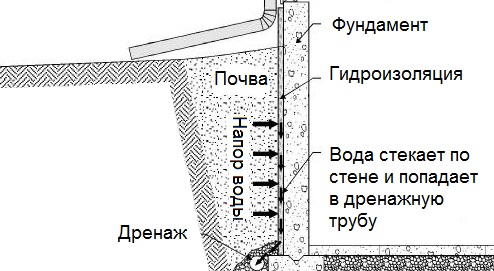

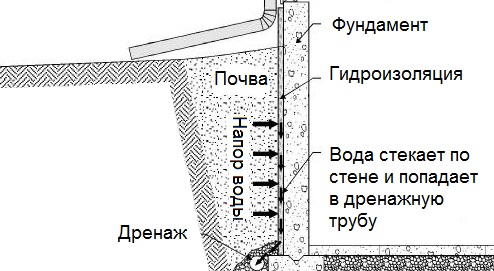

Общие условия выбора системы дренажа: Система дренажа выбирается в зависимости от характера защищаемого...

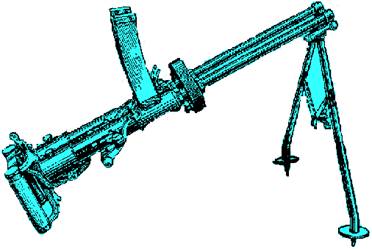

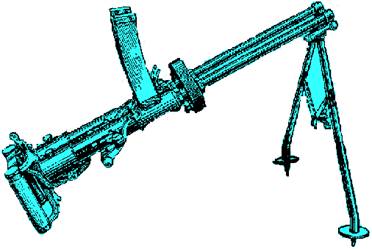

История развития пистолетов-пулеметов: Предпосылкой для возникновения пистолетов-пулеметов послужила давняя тенденция тяготения винтовок...

Общие условия выбора системы дренажа: Система дренажа выбирается в зависимости от характера защищаемого...

История развития пистолетов-пулеметов: Предпосылкой для возникновения пистолетов-пулеметов послужила давняя тенденция тяготения винтовок...

Топ:

Устройство и оснащение процедурного кабинета: Решающая роль в обеспечении правильного лечения пациентов отводится процедурной медсестре...

Организация стока поверхностных вод: Наибольшее количество влаги на земном шаре испаряется с поверхности морей и океанов...

Интересное:

Принципы управления денежными потоками: одним из методов контроля за состоянием денежной наличности является...

Подходы к решению темы фильма: Существует три основных типа исторического фильма, имеющих между собой много общего...

Распространение рака на другие отдаленные от желудка органы: Характерных симптомов рака желудка не существует. Выраженные симптомы появляются, когда опухоль...

Дисциплины:

|

из

5.00

|

Заказать работу |

Содержание книги

Поиск на нашем сайте

|

|

|

|

The complete pattern of human heterosexuality is not found in any other species (social-class differences in sexual behavior, pair-bonding, face-to-face copulation, hidden menstruallestrous cycles, oral and anal intercourse, etc.), although any single aspect of human heterosexuality can be found in some animal species. The same statement can be made about human homosexuality.

—JAMES D. WEINRICH39

It is ironic that this last assertion about how human beings are unique in their sexual behavior should have been made by the same scientist who commented on how rarely such statements of human uniqueness prove to be true. Indeed, now that more detailed and comprehensive information is available about animal homosexuality, it appears that at least three species rival, if not equal, human beings in the variability and “completeness” of their sexual expression: Bonobos, Orang-utans, and Bottlenose Dolphins. For each of the features mentioned above, an identical or equivalent aspect of behavior can be found, at least in a same-sex context. While none of these species has rigidly stratified “social classes,” there are discernible differences in sexual behavior between animals of different ages and social statuses. Homosexual activity is often more frequent in younger, lower-ranking female Bonobos who have recently joined a new troop, for instance, while younger individuals are often “on the top” during female homosexual interactions and “on the bottom” during male homosexual interactions. There is also some evidence that sexual activity between females occurs more often when they belong to distant rank classes. Adolescent or younger-adult Orang-utans participate in same-sex activities more than older, higher-ranking individuals and also exhibit distinctive heterosexual patterns. Younger male Bottlenose Dolphins tend to form their own groups in which same-sex activity is more common than among pair-bonded individuals—while adult males in this species generally do form lifelong bonds with each other.

Although Bonobos do not have exclusive pair-bonding per se, females do form long-lasting bonds with each other that include sexual interactions; adolescent females also typically pair up with an older “mentor” female when they arrive in a new group and engage in sexual activity most frequently with her. Orang-utans often form pairlike consortships in heterosexual contexts, and similar sorts of associations also occur in homosexual contexts. Sexual interactions between female Bonobos usually occur in a face-to-face position, as do heterosexual (and some homosexual) interactions in Orang-utans, as well as most copulations in Bottlenose Dolphins (for the latter, a “belly-to-belly” position is perhaps a more apt characterization). “Hidden estrous cycles” refers to the fact that no overt physical changes signal the various phases of a woman’s sexual cycle. A female Bonobo’s sexual skin swells with her cycle, although it is present for the majority of the cycle and is not associated specifically with ovulation. Bottlenose Dolphins do not generally give any visual cues as to their sexual cycles or timing of ovulation, nor do female Orang-utans.40 In any case, all three species engage in sexual activity throughout the female’s cycle the way human beings do, which is one important consequence of concealed sexual cycles in humans. Finally, Bonobos, Orang-utans, and Bottlenose Dolphins all engage in forms of anal and oral sex (the latter including fellatio in Bonobos and Orangs, cunnilingus in Orang-utans, and beak-genital propulsion in Dolphins).41

One area relating to sexual variability where animal and human homosexuality have been claimed to be comparable, rather than different, concerns the variety of sexual acts or positions used in homosexual as opposed to heterosexual contexts. Masters and Johnson found that gays and lesbians in long-term relationships often had better sexual technique and more variety in their sex lives than married heterosexuals. James Weinrich has suggested a parallel to this observation among animals, claiming that animals that engage in same-sex activity are, in a sense, sexual “virtuosos,” employing a wider range of sexual behaviors, positions, or techniques than do their heterosexual counterparts.42 Although the validity of this claim with respect to human beings cannot be directly addressed here, its accuracy with respect to animals can be assessed—and it appears that in this case the situation is considerably more complex than previously supposed.

It is certainly true that homosexual repertoires have a wider range of sexual acts than heterosexual repertoires in a number of species. In Stumptail and Crab-eating Macaques, for instance, oral sex and mutual masturbation occur primarily, if not exclusively, between same-sex partners. Male Bonobos have a form of mutual genital rubbing known as penis fencing that is unique to same-sex interactions. Male West Indian Manatees employ a wider variety of positions and forms of genital stimulation during sex with each other than do opposite-sex partners. Various types of anal or rump stimulation (besides mounting or intercourse) occur in homosexual but not heterosexual contexts in several Macaque species, Siamangs, and Savanna Baboons. Only same-sex partners participate in reciprocal mounting in at least 15 species, including Bonnet Macaques, Mountain Zebras, Koalas, and Pukeko.43

This does not, however, appear to be part of an overall pattern, especially where sexual activities other than mounting or intercourse are concerned. For example, of the 36 species (exhibiting homosexual behavior) in which some form of oral sex is practiced, in only 10 (28 percent) of these is oral-genital stimulation limited to homosexual contexts, and in some cases (e.g., Rhesus Macaques, Caribou, Walruses, Lions) genital licking is a uniquely heterosexual act. Similarly, manual stimulation of the genitals or masturbation between partners is limited to same-sex interactions in 15 of the 27 species (55 percent) where this behavior occurs; in the remaining animals, both heterosexual and homosexual (or, in some cases, only heterosexual) partners are involved. Even anal or rump stimulation (besides intercourse) is found in heterosexual contexts in half of the species (6 of 12) that engage in such activities. Combining these observations, we find that a variety of sexual acts are part of both heterosexual and homosexual repertoires in the majority of cases, with behaviors unique to same-sex interactions occurring only in about 40 percent of the cases.

As a matter of fact, in most instances both heterosexual and homosexual acts are equally “uninspired,” involving nothing more exotic than mounting behavior in the front-to-back position typical of mating in most animals. Even considering animals where other mounting positions are used, however, it is overly simplistic to claim that same-sex activity involves more “versatility.” In many species a variety of positions are employed in both heterosexual and homosexual situations. Furthermore, even though their frequency of use differs depending on the context, the major distinctions in mounting positions often lie along lines of gender rather than sexual orientation. The differentiating factor is not whether sexual activity involves partners of the same or opposite sex, but whether it involves males (in either heterosexual or homosexual contexts). For example, a face-to-face position is used for roughly 99 percent of sexual interactions between female Bonobos, but rarely in male-female interactions. However, a face-to-face position is almost equally rare in male homosexual interactions, occurring in only about 2 percent of activity between males. Thus, male homosexuality is more similar to heterosexuality than either is to female homosexuality in terms of the frequency of use of these two basic positions. A similar pattern occurs in Gorillas: although the face-to-face position is virtually absent in heterosexual encounters and much more common in homosexual ones, the two sexes have almost opposite preferences for this position. Almost three-quarters of female homosexual encounters involve the face-to-face position, while more than 80 percent of male homosexual mountings involve the front-to-back position (also preferred for heterosexual encounters). In Hanuman Langurs, male homosexuality is also more similar to heterosexuality than is female homosexuality in terms of the way that interactions are initiated: both males and females typically invite males to mount them by performing a special “head-shaking” display, which is much less characteristic of mounting between females.44

In Japanese Macaques, female homosexuality is more similar to heterosexuality than to male homosexuality in terms of the variety of positions used. In contrast, male homosexuality is more similar to heterosexuality than female homosexuality in terms of the frequency that various positions are used. In this species, fully seven different mounting positions can be identified, including four varieties of the front-to-back posture (with the mounting animal sitting, lying, or standing—with or without clasping its partner’s legs—behind the mountee), two types of face-to-face positioning (sitting or lying down), and sideways mounts. All seven of these positions are found in both heterosexual and female homosexual encounters, while male homosexual mounting employs only five of the seven (sitting or lying on the partner in a front-to-back position are not used). However, sexual encounters between females differ from both heterosexual and male homosexual mounts in using the face-to-face position more often, and in using the double-foot-clasp posture less than 20 percent of the time (compared to 75–85 percent of the time for sexual encounters where males are involved, either heterosexual or homosexual).45

Other patterns based on the intersection of gender and sexual orientation also occur. In Stumptail Macaques, for example, female homosexual encounters use three basic positions (standing or sitting front-to-back and sitting face-to-face), heterosexual activity uses two of these (standing or sitting front-to-back), while male homosexual activity uses only one of these (standing front-to-back). (Males do, however, employ a wider range of oral and manual forms of genital stimulation in their encounters with each other.) Copulations between female Flamingos generally resemble heterosexual matings more than they do mountings between male Flamingos, but same-sex copulations in birds of either sex differ from heterosexual activity in their lack of a particular “hooking” posture.46 Male White-handed Gibbons interact sexually with other males only in a face-to-face position and with females only in a front-to-back position—thus, homosexual and heterosexual interactions are equally “flexible” or “inflexible” in this species, but differ in which position is preferred in each context. Even reciprocal or reverse mounting—in which partners take turns mounting each other—is part of the heterosexual repertoire in more than three-quarters of the species that engage in this activity (in either same-or opposite-sex contexts); it is unique to heterosexual relations in many of these (including Western Gulls and Silvery Grebes) and present in many animals that do not engage in homosexual behavior at all.

Female Japanese Macaques in a sexual embrace. This face-to-face position is less common during heterosexual and male homosexual interactions.

In fact, it is sometimes the case that opposite-sex partners show more variability or flexibility in their sexual activity Heterosexual copulation in Botos occurs in three main positions (all belly-to-belly, either head-to-head, or head-to-tail, or at right angles) while homosexual copulation usually uses only one of these (head-to-head). 47 Both heterosexual and homosexual encounters in this species can involve two different forms of penetration (genital slit or blowhole), although same-sex activity also includes a third option, anal penetration. Among birds, the overwhelming majority of species mate in the standard position of one individual mounted on the other’s back, in both heterosexual and homosexual contexts. The only examples of other positions being used with any regularity involve male-female mounts: a facing position (extremely unusual for birds) is used by stitchbirds, for instance, who mate with the female lying on her back and the male on top of her, and in purple-throated Carib hummingbirds, who mate belly-to-belly while perched on a branch. Copulation in red-capped plovers is achieved by the male first throwing himself on the ground on his back, then pulling the female on top of him in a facing position. Vasa parrots have an elaborate and (for birds) unusual form of genital contact in which the male inserts his genital protrusion (a bulbous swelling surrounding his genital orifice) inside the female’s cloaca, which extends and envelops his organ while the two birds transfer from a regular mounting position to a side-by-side position (full penetration does not usually occur in bird matings). Vervain hummingbirds actually mate in midflight while traversing an 80-foot trajectory low above the ground. Finally, several species of woodpeckers are true heterosexual virtuosos: in an acrobatic sequence the male first performs a standard front-to-back mount and then drops to one side of the female, making genital contact with his tail underneath hers and sometimes ending up on his back or with his entire body in a perpendicular or even upside-down position.48

“Virtuosity” in other areas of behavior is not generally exclusive to homosexual encounters either. The vast majority of courtship interactions, for example, involve the same set of behaviors typical for the species regardless of whether they are being performed between partners of the same or the opposite sex. There are notable exceptions, of course: the courtship “games” of female Rhesus Macaques and solicitations of female Japanese Macaques; “necking” interactions between male Giraffes; pirouette dances in male Ostriches; the vocal duets of Greylag gander pairs; aspects of courtship feeding in Laughing Gulls, Antbirds, Superb Lyrebirds, and Orange-fronted Parakeets; alternative bower displays in Regent Bowerbirds; and unique vocalizations during homosexual but not heterosexual interactions in male Emus and Japanese Macaques. Occasionally courtship activities are also performed at different rates or with different intensities: in same-sex pairs of Black-winged Stilts and Black-headed Gulls, for instance, certain courtship behaviors occur more frequently in same-sex pairs, others more commonly in opposite-sex pairs. All of these represent behavioral innovations in same-sex contexts, but they are atypical. Usually both homosexual and heterosexual courtships draw upon the same repertoire of behaviors, and in many cases same-sex interactions actually involve only a subset of the full behavioral suite that is characteristic of the species.

Thus, while homosexuality among animals is sometimes characterized by innovative or exceptional behaviors not found in heterosexual interactions, the opposite situation is equally, if not more, prevalent. It seems, then, that neither virtuosity nor mundanity of sexual expression are exclusive to either homosexual or heterosexual contexts. This is really not surprising: as we have already seen, a hallmark of sexual (and related) behaviors in animals is the tremendous range of variation found between species as well as among different individuals. For just about any pattern or trend that can be discerned, one that is contradictory or equivocal can be found. It stands to reason, then, that something like “sexual technique” would exhibit a similar range of diversity. And although Masters and Johnson may have found a greater level of technical proficiency in sex among some homosexual couples, this is probably an overly simplistic generalization even among people. A wider study sample that includes extensive cross-cultural information, as well as closer attention to age, gender and class differences, social contexts, and other factors, would likely reveal that (once again) human beings are much more like other species in this regard.

|

|

|

Поперечные профили набережных и береговой полосы: На городских территориях берегоукрепление проектируют с учетом технических и экономических требований, но особое значение придают эстетическим...

Биохимия спиртового брожения: Основу технологии получения пива составляет спиртовое брожение, - при котором сахар превращается...

Папиллярные узоры пальцев рук - маркер спортивных способностей: дерматоглифические признаки формируются на 3-5 месяце беременности, не изменяются в течение жизни...

Общие условия выбора системы дренажа: Система дренажа выбирается в зависимости от характера защищаемого...

© cyberpedia.su 2017-2025 - Не является автором материалов. Исключительное право сохранено за автором текста.

Если вы не хотите, чтобы данный материал был у нас на сайте, перейдите по ссылке: Нарушение авторских прав. Мы поможем в написании вашей работы!