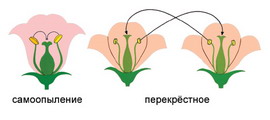

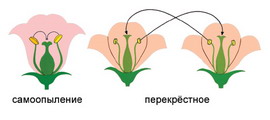

Семя – орган полового размножения и расселения растений: наружи у семян имеется плотный покров – кожура...

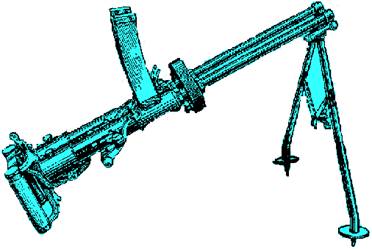

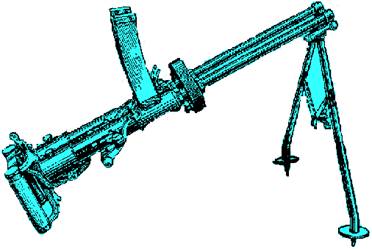

История развития пистолетов-пулеметов: Предпосылкой для возникновения пистолетов-пулеметов послужила давняя тенденция тяготения винтовок...

Семя – орган полового размножения и расселения растений: наружи у семян имеется плотный покров – кожура...

История развития пистолетов-пулеметов: Предпосылкой для возникновения пистолетов-пулеметов послужила давняя тенденция тяготения винтовок...

Топ:

Выпускная квалификационная работа: Основная часть ВКР, как правило, состоит из двух-трех глав, каждая из которых, в свою очередь...

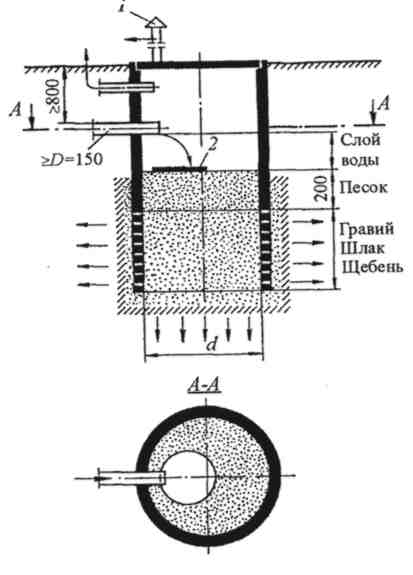

Методика измерений сопротивления растеканию тока анодного заземления: Анодный заземлитель (анод) – проводник, погруженный в электролитическую среду (грунт, раствор электролита) и подключенный к положительному...

Интересное:

Средства для ингаляционного наркоза: Наркоз наступает в результате вдыхания (ингаляции) средств, которое осуществляют или с помощью маски...

Аура как энергетическое поле: многослойную ауру человека можно представить себе подобным...

Лечение прогрессирующих форм рака: Одним из наиболее важных достижений экспериментальной химиотерапии опухолей, начатой в 60-х и реализованной в 70-х годах, является...

Дисциплины:

|

из

5.00

|

Заказать работу |

… two males (Dinding and Durian) regularly mouthed the penis of the other on a reciprocal basis. This behavior, however, may be nutritively rather than sexually motivated.

—T. L. MAPLE, Orang-utan Behavior 100

In nearly a quarter of all animals in which homosexuality has been observed and analyzed, the behavior has been classified as some other form of nonsexual activity besides (or in addition to) dominance. Reluctant to ascribe sexual motivations to activities that occur between animals of the same gender, scientists in many cases have been forced to come up with alternative “functions.” These include some rather far-fetched suggestions, such as the idea (quoted above) that fellatio between male Orang-utans is a “nutritive” behavior, or that episodes of cavorting and genital stimulation between male West Indian Manatees are “contests of stamina.”101 At various times, homosexuality has also been classified as a form of aggression (not necessarily related to dominance), appeasement or placation, play, tension reduction, greeting or social bonding, reassurance or reconciliation, coalition or alliance formation, and “barter” for food or other “favors.” It is striking that virtually all of these functions are in fact reasonable and possible components of sexuality—as any reflection on the nature of sexual interactions in humans will reveal—and indeed in some species homosexual interactions do bear characteristics of some or all of these activities. However, in the vast majority of cases these functions are ascribed to a behavior instead of, rather than along with, a sexual component—and only when the behavior occurs between two males or two females. According to Paul L. Vasey, “While homosexual behavior may serve some social roles, these are often interpreted by zoologists as the primary reason for such interactions and usually seen as negating any sexual component to this behavior. By contrast, heterosexual interactions are invariably seen as being primarily sexual with some possible secondary social functions.”102

Thus, a widespread double standard exists when it comes to classifying behavior as “sexual.” Desexing is selectively applied to homosexual but not heterosexual activities, according to a number of different strategies. The first and most obvious is when scientists explicitly classify the same behavior as sexual when it takes place between members of the opposite sex and nonsexual when it involves members of the same sex. This is readily apparent in the following statement: “Mounting [in Bison] can be referred to as ‘mock copulation.’ It seems appropriate to classify this action as sexual behavior only when it is directed towards females. The gesture, however, was also directed to males which suggests that it also has a social function.” Likewise, because a behavior often associated with courtship in Asiatic Mouflons and other Mountain Sheep (the foreleg kick) was observed more frequently between individuals of the same sex than of the opposite sex, one zoologist concluded that this activity must therefore be aggression rather than courtship. Primatologists reassigned what they had initially classified as sexual behavior in Stumptail Macaques to the category of aggressive or dominance behavior when it took place in homosexual pairs, while marine biologists reclassified courtship and mating activity in Dugongs as nonsexual play behavior once they learned both participants were actually male. Ornithologists studying the courtship display of Laysan Albatrosses also questioned whether this behavior was “truly” related to pair-bonding or mating after they discovered that some courting birds were of the same sex. Finally, because (male) Dwarf Mongooses and Bonnet Macaques are as likely to mount same-sex as opposite-sex partners, scientists decided this behavior must be nonsexual.103 This is not to say that behaviors cannot have different meanings or “functions” in same-sex versus opposite-sex contexts, only that the erasure by zoologists of sexual interpretations from same-sex contexts has been categorical and nearly ubiquitous.

Not only do zoologists apply nonsexual interpretations to behaviors when they know that the participants are of the same sex, they also do the reverse, assuming that a superficially nonsexual behavior—especially if it involves aggression—must involve animals of the same sex. A particularly interesting example of these assumptions concerns the flip-flop in interpretation of sexual chases in Redshanks, part of the courtship repertoire of this sandpiper. Because of their somewhat aggressive nature, these chases were originally interpreted as a nonsexual, territorial interaction and assumed to involve two males—in spite of the fact that some scientists reported seeing chases between birds of the opposite sex. Subsequently, more detailed study involving banded birds (enabling individual identification) revealed that most chases did in fact involve a male and a female and occurred early in the breeding season—at which point the behavior was reclassified as a form of courtship. However, it was also discovered that in a few instances two males were actually chasing each other—and of course scientists then tried to claim that, only in these cases, the chasing was once again nonsexual (in spite of the fact that the two males often copulated with each other as well).104

Sometimes the arbitrary categorization of behaviors reaches absurd levels. In a few instances components of one and the same activity are given separate classifications, or the undeniably sexual character of a homosexual interaction is taken to mean only that the activity is “usually” heterosexual. For example, in one report on female Crested Black Macaques, a behavior labeled the “mutual lateral display” is classified as a “sociosexual” activity, i.e., not fully or exclusively sexual. It is described as a “distance-reducing display” or a form of “greeting” that “precedes grooming or terminates aggression between two animals.” Yet the fact that females masturbate each other’s clitoris during this “display”—about as definitively sexual as a behavior can get—is inexplicably omitted from the description of this activity. Instead, this detail is included separately in the “sexual behavior” section of the report under the heading “masturbation”—a contradictory recognition that, apparently, part of this behavior is not truly sexual yet part of it is! In the same species, males often become sexually aroused while grooming one another, developing erections and sometimes even masturbating themselves to ejaculation. Amazingly, this is interpreted by another investigator not as evidence of the sexual nature of grooming between males, but rather that grooming is probably an activity “typically” performed by females to males prior to copulation. Apparently such overt sexuality could only be a case of misplaced heterosexuality, not “genuine” homosexuality.105

Often a behavior is automatically assumed to involve courtship or sexuality when its participants are known to be of the opposite sex—and the criteria for a “sexual” interpretation are generally far less stringent than those applied to the corresponding interactions between like-sexed individuals. In other words, heterosexual interactions are given the benefit of the doubt as to their sexual content or motivation, even when there is little or no direct evidence for this or even overt evidence to the contrary. For example, simple genital nuzzling of a female Vicuna by a male—taking place outside of the breeding season, and without any mounting or copulation to accompany it—is classified as sexual behavior, while actual same-sex mounting in the same species is considered nonsexual or “play” behavior. In Musk-oxen, foreleg-kicking in heterosexual contexts is often much more aggressive than in homosexual contexts. The male’s blow to a female’s spine or pelvis is sometimes so forceful that it can be heard up to 150 feet away, yet this behavior is still classified as essentially courtship-oriented. If this level of aggression were exhibited in foreleg-kicking between males, the behavior would never be considered homosexual courtship (as it is, this classification is granted only grudgingly, accompanied by the obligatory reference to its “dominance” function between males).

When a male Giraffe sniffs a female’s rear end—without any mounting, erection, penetration, or ejaculation—he is described as being sexually interested in her and his behavior is classified as primarily, if not exclusively, sexual. Yet when a male Giraffe sniffs another male’s genitals, mounts him with an erect penis, and ejaculates—then he is engaging in “aggressive” or “dominance” behavior, and his actions are considered to be, at most, only secondarily or superficially sexual. In one study of Bank Swallows, all chases between males and females were assumed to be sexual even though they were rarely seen to result in copulation. Indeed, the majority of bird studies label dyads composed of a male and female as “[heterosexual] pairs” in spite of the fact that overt sexual (mounting) activity is rarely verified for all such couples. In contrast, most investigators will not even consider classifying same-sex interactions in birds to be courtship, sexual, or pair-bonding activity—even when they involve the same behavior patterns used in heterosexual contexts—unless mounting is observed. Certain associations between male and female Savanna Baboons and Rhesus Macaques are described as “sexual” relationships or “pair-bonds” even though they often do not include sexual activity. In contrast, bonds between same-sex individuals in these species are characterized as nonsexual “coalitions” or “alliances” even though they may involve sexual activities (as well as the same intensity and longevity found in heterosexual bonds). Finally, the “piping display” of the Oystercatcher described earlier was initially assumed to be a courtship behavior, largely because it is a common activity between males and females. Subsequent studies have shown that this is in fact a primarily nonsexual (territorial or dominance) interaction.106

Another strategy adopted by scientists when confronted with an apparently sexual behavior occurring between two males or two females is to deny its sexual content in both same-sex and opposite-sex contexts. For example, because female Crested Black Macaques show behavioral signs of orgasm during homosexual as well as heterosexual mounts, one scientist concluded that this behavior is not reliable evidence of female orgasm in either situation. The fact that intercourse and other sexual interactions occur between like-sexed individuals in Bottlenose and Spinner Dolphins is often taken to be “proof” that such behaviors have become largely divorced from their sexual content and are now forms of “greeting” or “social communication,” even in heterosexual contexts. Similarly, copulation in Common Murres has many nonreproductive features: in addition to occurring between males, in heterosexual pairs it frequently takes place before the female becomes fertile. Drawing an explicit analogy with “nonsexual” mounting in primates, one ornithologist suggested that in this bird heterosexual mounting must therefore serve an “appeasement” function rather than being principally a sexual behavior, i.e., females invite their male partners to mate in order to deflect aggression from them. Likewise, nonprocreative copulations in both heterosexual and homosexual contexts in Blue-bellied Rollers are categorized as a form of ritualized aggression or appeasement.107

A difference in form between homosexual and heterosexual behaviors is often interpreted as a difference in their sexual content. The reasoning is that if same-sex activity does not resemble opposite-sex activity, and only opposite-sex activity is by definition sexual, then same-sex activity cannot be sexual. For example, in Rhesus Macaques most heterosexual copulations involve a series of mounts by the male, only the last of which typically involves ejaculation. Because mounts between males are often single rather than series mounts, they are frequently classified as nonsexual, even when they include clear signs of sexual arousal such as erection, pelvic thrusting, penetration, and even ejaculation. A similar interpretation has also been suggested for mounting between male Japanese Macaques. In contrast, significant differences in form also exist between heterosexual copulation in Macaques (with series mounting) and male masturbatory patterns, yet both activities are clearly sexual and are typically classified as such.108

In other animals the very characteristics that are used to claim that same-sex activities are nonsexual—their briefness, “incompleteness,” or absence of signs of sexual arousal, for example—are as typical, if not more typical, of opposite-sex interactions that are classified as sexual behavior. Nearly a third of all mammals in which same-sex mounting occurs also have “symbolic” or “incomplete” heterosexual mounts in which erection, thrusting, penetration, and/or ejaculation do not occur; “ritual” heterosexual mountings are also typical of many bird species.109 In Kob antelopes, 52 percent of heterosexual copulations involve at least one mount by the male without an erection; in contrast, 56 percent of homosexual mountings between male Giraffes—sometimes classified as nonsexual— do involve erections. Likewise, only one in four to five heterosexual mounts among northern jacanas results in cloacal (genital) contact, and ejaculation probably occurs in less than three-quarters of Orang-utan heterosexual mounts.110 Evidence for sexual arousal or “completed” copulations is often entirely lacking in heterosexual contexts, yet such male-female mounts are still considered “sexual” behavior. In Walruses, Musk-oxen, Bighorn Sheep, Asiatic Mouflons, Grizzly Bears, and Olympic Marmots, for example, penetration and ejaculation are rarely, if ever, directly observable during heterosexual mounts, while male erections are routinely not visible during White-tailed Deer copulations, ejaculation can only be “assumed” to occur in observations of Orang-utan, White-faced Capuchin, and Northern Fur Seal heterosexual mating, and genital contact is difficult to verify during Ruff male-female mounts (among many other species).111

In fact, actual sperm transfer during heterosexual copulations in many species is so difficult to observe that biologists have had to develop a variety of special “ejaculation-verification” techniques. In birds such as Tree Swallows, for example, tiny glass beads or “microspheres” of various colors are inserted into males’ genital tracts. If the birds ejaculate during a heterosexual mating, these beads are transferred to the female’s genital tract, where they can be retrieved by scientists and checked for their color coding to determine which males have actually transferred sperm. For rodents and small marsupials, biologists actually inject several different radioactive substances into males’ prostate glands. During ejaculation, these are carried via semen into females, who are then monitored with a sort of “sperm Geiger counter” to determine which males, if any, have inseminated them.112 If such elaborate lengths are required to verify a fundamental and purportedly self-evident aspect of heterosexual mating, is it any wonder that homosexual matings should sometimes appear to be “incomplete”?

Because of such difficulties in observation and interpretation, scientists have often employed similarly extreme measures in an attempt to “verify” homosexual intercourse. In the early 1970s, for example, a controversy arose concerning to what extent, if at all, mounting activity between male animals was truly “sexual.” As proof of its “nonsexual” character, some scientists claimed that full anal penetration never occurred in such contexts (thus equating penetration with “genuine” sexuality). Researchers actually went to the trouble of filming captive male Rhesus Macaques mounting each other in order to record examples of anal penetration; they even anesthetized the monkeys afterward to search for the presence of semen in their rectums. Needless to say, the cinematographic proof of anal penetration they obtained did little to quell any subsequent debate about whether such mounts were “sexual”—all it did was institute a revised definition of “sexual” activity. The fact that they were able to document penetration but not ejaculation simply meant that a new “standard” of sexuality could now be applied: only mounts that culminated in ejaculation were to be considered “genuine” sexual behavior. Ironically, none of these researchers were apparently aware of an earlier field report of homosexual activity in Rhesus Macaques in which both anal penetration and ejaculation were observed.113

This near-obsessive focus on penetration and ejaculation—indeed, on “measuring” various aspects of sexual activity to begin with—reveals a profoundly phallocentric and “goal-oriented” view of sexuality on the part of most biologists. Not just homosexual activity, but noninsertive sexual acts, female sexuality and orgasmic response, oral sex and masturbation, copulation in species (such as birds) where males do not have a penis—any form of sex whatsoever that does not involve penis-vagina penetration falls off the map of such a narrow definition. The fact is that both heterosexual and homosexual activities exist along a continuum with regard to their degree of “sexuality” or “completeness.” Male mammalian mounting behavior, for example, can involve partial mounting, full mounting but no thrusting, thrusting but no erection, erection but no penetration, penetration but no ejaculation, ejaculation but no penetration, penetration and ejaculation without series mounting, and so on and so forth.114 Each stage along this continuum has at one time or another been considered a defining threshold of “true” sexual behavior—often so as to exclude same-sex interactions—rather than as one possible manifestation of a broader sexual capacity that is sometimes, but not always, orgasmically (or genitally) focused.

A nonsexual component of homosexual behavior does appear to be valid in a number of species; in equally many species, there are clear arguments against various nonsexual interpretations, and some zoologists have themselves explicitly refuted nonsexual analyses.115 Overall, though, three important points must be considered in relation to nonsexual interpretations of behaviors between animals of the same sex. First, the question of causality—or the primacy of the nonsexual aspect—must be addressed. Just because an apparently sexual behavior is associated with a nonsexual result or circumstance does not mean that the sole function or context of the behavior is nonsexual. For example, female Japanese Macaques often gain powerful allies by forming homosexual associations, since their consorts typically support them in challenging (or defending themselves against) other individuals. However, a detailed study of partner choices showed that such nonsexual benefits are of secondary importance: females choose their consorts primarily on the basis of sexual attraction rather than on whether they will make the best or most strategic allies.116 Likewise, mounting (or other sexual activity) between animals of the same sex is described in many species (e.g., Bonobos) as a behavior that serves to reduce aggression or tension between the participants. Indeed, individuals who mount each other may be less aggressive to one another or may experience less tension in their mutual interaction, and homosexuality probably does serve a tension-reducing function for at least some animals in some contexts (as does heterosexuality). However, the situation is considerably more involved than this. Tension reduction is as likely to be a consequence of an affiliative or friendly relationship between individuals—a relationship that is also expressed through sexual contact—as it is to be a direct result of their sexual activity. Moreover, as some researchers have pointed out for Bonobos, the causal relationship may also be the reverse of what is usually supposed. That sexual behavior and situations involving tension often co-occur in this species can give the impression that sexuality is functioning only to reduce tension, when in fact it may also create or generate its own tension. Indeed, homosexual activity in male Gorillas often results in increased rather than decreased social tension.117

Second, even if behaviors are classified as nonsexual or having a nonsexual component, the behavioral categories to which they are assigned (aggression, greetings, alliance formation, etc.) are not monolithic. Many important questions remain concerning the forms and contexts of such behaviors—questions that are often overlooked once they receive their “classification.” Just because we “know” that a given behavior is “nonsexual” does not mean that we then know everything about that behavior. Apparently sexual behaviors between males in both Bonnet Macaques and Savanna Baboons, for example, are classified as social “greetings” interactions. Yet there are fundamental differences between these two species, not only in the types of activities involved, but in the frequency of participation, the types of participants, the social framework and outcome of participation, and so on.118 Ultimately, classifying such behavior as “nonsexual” is as meaningless, misleading, and unilluminating as many investigators claim a sexual categorization is, if it obscures these differences or fails to address their origin.

Finally, the relationship between sexual and nonsexual aspects of behavior is complex and multilayered and does not fit the simple equations that are usually applied, namely same-sex participants = nonsexual, opposite-sex participants = sexual. In many species, there is clear evidence of the genuinely sexual aspect of behaviors between animals of the same sex, using the same criteria that are applied to heterosexual interactions—for example, penile or clitoral erection, pelvic thrusting, penetration (or cloacal contact), and/or orgasm.119 In still other species there is a gradation or cline between sexual and nonsexual behaviors that defies any rigid categorization—or else there is a sharp distinction between the two, with both occurring among animals of the same sex. Most importantly, the sexual and nonsexual aspects of a behavior are not mutually exclusive. An interaction involving genital stimulation between two males or two females can be a form of greeting, or a way of reducing tension or aggression, or a type of play, or a form of reassurance, or any number of different things—and still be a sexual interaction at the same time. Ironically, by denying the sexual component of many same-sex activities and seeking alternative “functions,” scientists have inadvertently ascribed a much richer and varied palette of behavioral nuances to homosexual interactions than is often granted to heterosexual ones.120 Because heterosexuality is linked so inextricably to reproduction, its nonsexual “functions” are often overlooked, whereas because homosexuality is typically disassociated from reproduction, its sexual aspects are often denied. By bringing these two views together—by recognizing that both same-sex and opposite-sex behaviors can be all these things and sexual, too—we will have come very close indeed to embracing a fully integrated or whole view of animal life and sexuality.

Chapter 4

Механическое удерживание земляных масс: Механическое удерживание земляных масс на склоне обеспечивают контрфорсными сооружениями различных конструкций...

История развития хранилищ для нефти: Первые склады нефти появились в XVII веке. Они представляли собой землянные ямы-амбара глубиной 4…5 м...

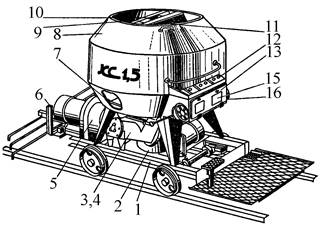

Кормораздатчик мобильный электрифицированный: схема и процесс работы устройства...

Индивидуальные очистные сооружения: К классу индивидуальных очистных сооружений относят сооружения, пропускная способность которых...

© cyberpedia.su 2017-2024 - Не является автором материалов. Исключительное право сохранено за автором текста.

Если вы не хотите, чтобы данный материал был у нас на сайте, перейдите по ссылке: Нарушение авторских прав. Мы поможем в написании вашей работы!