Типы оградительных сооружений в морском порту: По расположению оградительных сооружений в плане различают волноломы, обе оконечности...

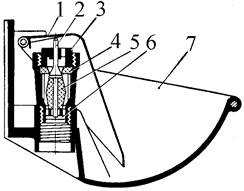

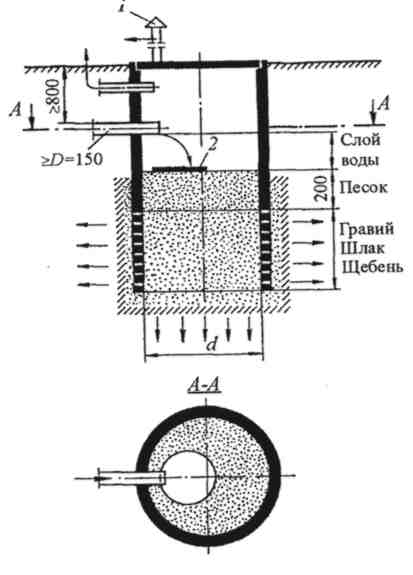

Индивидуальные и групповые автопоилки: для животных. Схемы и конструкции...

Типы оградительных сооружений в морском порту: По расположению оградительных сооружений в плане различают волноломы, обе оконечности...

Индивидуальные и групповые автопоилки: для животных. Схемы и конструкции...

Топ:

Когда производится ограждение поезда, остановившегося на перегоне: Во всех случаях немедленно должно быть ограждено место препятствия для движения поездов на смежном пути двухпутного...

Генеалогическое древо Султанов Османской империи: Османские правители, вначале, будучи еще бейлербеями Анатолии, женились на дочерях византийских императоров...

Характеристика АТП и сварочно-жестяницкого участка: Транспорт в настоящее время является одной из важнейших отраслей народного хозяйства...

Интересное:

Инженерная защита территорий, зданий и сооружений от опасных геологических процессов: Изучение оползневых явлений, оценка устойчивости склонов и проектирование противооползневых сооружений — актуальнейшие задачи, стоящие перед отечественными...

Лечение прогрессирующих форм рака: Одним из наиболее важных достижений экспериментальной химиотерапии опухолей, начатой в 60-х и реализованной в 70-х годах, является...

Подходы к решению темы фильма: Существует три основных типа исторического фильма, имеющих между собой много общего...

Дисциплины:

|

из

5.00

|

Заказать работу |

Содержание книги

Поиск на нашем сайте

|

|

|

|

… preferential or obligatory adult homosexuality is not found naturally in any mammalian species other than Homo sapiens.

—W. J. GADPAILLE, 1980

Homosexual human couples who remain together throughout their adult life have few, if any, counterparts in wild mammals as far as is known at present.

—ANNE INNIS DAGG, 1984

Exclusive homosexual behavior appears to be absent among nonhuman primates …

—PAUL L. VASEY, 19958

An oft-repeated claim about homosexuality is that exclusive, lifetime, or “preferential” homosexual activity is unique to human beings, or at least rare among animals (especially among primates and other mammals). This is really a question of sexual orientation—that is, to what extent do animals engage in sexual and related activities with members of the same sex without also engaging in such activities with members of the opposite sex? In fact, exclusive homosexuality of various types occurs in more than 60 species of nondomesticated mammals and birds, including at least 10 kinds of primates and more than 20 other species of mammals.9 In this section we’ll consider these various forms of homosexual orientation and compare them to the wide variety of bisexualities that are also found throughout the animal world.

When discussing the question of exclusive homosexuality, several factors need to be distinguished: the length of time that exclusivity is maintained (short-term versus long-term, including lifetime), the social context and type of same-sex activity involved (pair-bonding versus promiscuity in nonbreeding animals, for example), the type of animal involved (e.g., mammal versus bird), and the degree of exclusivity (e.g., absolute absence of opposite-sex activity versus primary homosexual associations with occasional heterosexual ones, and vice versa). These factors combine in various ways and interact with each other to produce a number of different patterns. To begin with, we will consider long-term or extended exclusivity, since this pattern appears to be the most contested as to its existence among animals. Because species vary widely as to their life expectancy, onset of sexual maturity, and period of adulthood, it is difficult to come up with an absolute definition of long-term that has wide applicability. For the purposes of this discussion, though, we will somewhat arbitrarily consider homosexual activity that continues for less than two consecutive years (or breeding seasons) to be short-term, while anything continuing longer is considered extended or long-term, with the understanding that the latter category includes a wide spectrum of possibilities, anywhere from 3 years to a life span of over 40 years.

The only way to absolutely verify lifetime exclusive homosexuality is to track a large number of individuals from birth to death and record all the various homosexual or heterosexual involvements they have. Needless to say, this is a difficult task to accomplish (especially in the wild) and has been achieved for only a few species—indeed, in many cases the comparable evidence for lifetime exclusive heterosexuality is not available either, for precisely the same reasons. Nevertheless, in at least three species of birds—Silver Gulls, Greylag Geese, and Humboldt Penguins—fairly extensive tracking regimes have been conducted, and individuals who form only homosexual pair-bonds throughout their entire lives have been documented. In some cases these are continuous pair-bonds that last upward of 15 years in Greylag Geese and 6 years in Humboldt Penguins (until the death of the individuals involved), while in other cases (e.g., Silver Gulls) individuals may also have several same-sex partnerships during their lives (either because of “divorce” or death of the partners).10

While absolute verification of lifetime homosexuality is not directly available for other species, extended periods of same-sex activity, perhaps even lifelong, are strongly suggested. In Galahs, Common Gulls, Black-headed Gulls, Great Cormorants, and Bicolored Antbirds, for example, specific homosexual partnerships have been documented as lasting for as long as six years (or individuals having several consecutive homosexual associations for that length of time); in most of these cases the absence of heterosexual activity for at least one partner has been documented or is highly likely. In many other bird species, same-sex partnerships that last anywhere from several years to life probably also occur: Black Swans, Ring-billed Gulls, Western Gulls, and Hooded Warblers, for instance. Although these durations have not been confirmed in specific individuals, homosexual pairs that continue for at least two years or birds who consistently form same-sex pairs for that time have been verified.11 In still other cases, long-term same-sex bonds undoubtedly occur because homosexual pairs in these species typically follow the pattern of heterosexual pairs, which are usually lifelong (or of many years duration): Black-winged Stilts, Herring Gulls, Kittiwakes, Blue Tits, and Red-backed Shrikes, among others. Finally, it must also be remembered that in many animals (e.g., Pied Kingfishers), same-sex (and opposite-sex) pair-bonds that last two to three years can still be lifelong, owing to the relatively short life span of the species.

In mammals, cases of long-term, exclusively homosexual pairing are indeed rare. One example is male Bottlenose Dolphins: the majority of males in some populations form lifelong homosexual pairs, specific examples of which have been verified as lasting for more than ten years and continuing until death. Although the sexual involvements (both same- and opposite-sex) of such individuals have not in all cases been exhaustively tracked, it is quite likely that at least some of these animals have little or no sexual contact with females (since breeding rates tend to be low in Bottlenose communities, with many individuals not participating in reproduction each year and, by extension, possibly throughout their lives).12 Absolute verification in this species, however, may not be forthcoming, since it is virtually impossible to continuously monitor the sexual behavior of all individuals within a given population of an oceangoing species. Bottlenose Dolphins are exceptional, however, in that the homosexual pattern in this species is distinct from the heterosexual one: opposite-sex pair-bonding does not occur among Bottlenose Dolphins. In most other species, homosexual and heterosexual activities tend to follow the same basic patterns, whether this means pair-bonding, polygamy, promiscuity, or some other arrangement.13 Lifetime homosexual couples are not prevalent among mammals, therefore, for the same reason that lifetime heterosexual couples are not: monogamous pair-bonding is simply not a common type of mating system in mammals (it is found in only about 5 percent of all mammalian species).14

Nevertheless, long periods of exclusive homosexuality among mammals have been documented for other social contexts besides pair-bonding. In many species, significant portions of the population do not engage in breeding or heterosexual pursuits for at least a part of their lives. Because some of these animals continue to engage in same-sex interactions, however, they are exclusively homosexual for at least that time, which can be considerable. Among Gorillas, for example, males often live in sex-segregated groups where homosexual activity takes place. The average length of stay in a male-only group is more than six years, although some males remain in such exclusively homosexual environments for much longer. One individual lived in an all-male group for ten years, staying until his death, and nearly a third of the males who joined the group over a thirteen-year study period were still with the group at the end of that time. Likewise, Hanuman Langur males may spend upward of five years in male-only bands in which homosexual activity takes place, and some individuals live their entire adult lives in such groups.15 In a number of hoofed mammals, a similar form of exclusivity based on sex segregation occurs: only a few individual males participate in heterosexual mating, while the remainder live in “bachelor herds” where homosexual activity often takes place.16 Among Mountain Zebras, for example, males stay an average of three years in such groups before joining breeding groups, and some remain their whole lives without ever mating heterosexually. Analogous patterns occur in a number of other species where only a relatively small percentage of males ever breed: antelopes and gazelles, including Blackbuck, Pronghorn, and Grant’s and Thomson’s Gazelles; Giraffe; Red Deer; Mountain Sheep; seals such as Northern Elephant Seals and Australian and New Zealand Sea Lions; and birds such as Ruffed Grouse, Long-tailed Hermit Hummingbirds, and Guianan Cock-of-the-Rock. In some hoofed mammals such as American Bison, a related age-based pattern is found. Males generally do not participate in heterosexuality until they are five to six years old; prior to that time, many engage in homosexual activities, entailing a period of exclusively same-sex activity of up to five years for some individuals.17

Other patterns of exclusivity occur as well. In Nilgiri Langurs and Hamadryas Baboons, for instance, generally only the highest-ranking male in a group mates with females; remaining males, if they engage in sexual activity at all, are sometimes involved only in homosexual pursuits. In Nilgiri Langurs, cases of nonbreeding males having only same-sex interactions for at least four years have been documented. In Ruffs, there are several different categories of males, many of whom rarely, if ever, mate heterosexually; some of these individuals participate in homosexual activities and may do so over an extended period, perhaps even for life. Finally, in some species same-sex activity may be exclusive because it is incestuous, involving a parent and its nonbreeding offspring. In male White-handed Gibbons, for instance, father-son sexual relations may continue for several years; the son is not involved in concurrent heterosexual activity, and sometimes even his father may have little or no opposite-sex mating during this time. Red Fox daughters can remain with their family group for many years—sometimes they never leave—during which time they may be involved in occasional same-sex mounting with their mothers (or each other) but no heterosexual activity.18

Thus, while in many species documentation of exclusive long-term homosexuality (or heterosexuality, for that matter) is not directly available, exclusivity can be inferred from the general patterns of social organization in the species. For example, a system that involves large numbers of nonbreeders (including individuals who never mate heterosexually during their entire lives), combined with homosexual activities among at least a portion of these nonbreeding animals (sometimes in sex-segregated groups), will invariably entail some individuals whose only sexual contacts are with animals of the same sex. For some animals this period of exclusive homosexuality lasts no more than a few years; for others, it may extend considerably longer, even for the duration of their lives.

Shorter periods of exclusive or “preferential” homosexuality also occur. Sexual “friendships” in Stumptail Macaques and Rhesus Macaques, for example, and homosexual consortships in Japanese Macaques, last anywhere from a few days to several months, during which time there are no heterosexual involvements. During the seasonal aggregations of male Walruses and Gray Seals, same-sex activity usually occurs to the exclusion of opposite-sex behavior. Female Marmots forgo breeding for a couple of years but may still have sexual contact with other females. Same-sex pair bonds in King Penguins and homosexual associations in female Orang-utans are also exclusive for their duration. Of course, many of these animals are actually bisexual because they also engage in heterosexual pursuits at other times during their lives, but while they are involved in same-sex activity, they do not simultaneously engage in opposite-sex behavior. Thus, when considering various forms of exclusive homosexuality it is also necessary to understand the different types of nonexclusive homosexuality—that is, bisexuality.

The participation of an individual in both homosexual and heterosexual activities is widespread among animals: bisexuality occurs in more than half of the mammal and bird species in which same-sex activity is found. Nevertheless, there are many different forms and degrees of bisexuality, and these must be carefully distinguished when discussing sexual orientation in animals. A useful differentiation to start with is sequential as opposed to simultaneous bisexuality, a distinction that hinges on the temporal or chronological separation between homosexual and heterosexual pursuits. In sequential or serial bisexuality, periods of exclusively same-sex activity alternate with periods of exclusively opposite-sex activity. In simultaneous bisexuality, homosexual and heterosexual activities co-occur or are interspersed within a relatively short period (say, within the same mating season). Thus, many of the “shorter” periods of exclusive homosexuality that we have been considering actually fall into a larger pattern of sequential bisexuality, which itself forms a continuum in which same-sex activity may occupy anywhere from several months to several decades of an animal’s life. Moreover, the “sequentiality” of bisexual experience assumes many different forms: a seasonal pattern (for example, in Walruses, who engage in homosexuality primarily outside of the breeding season, or in Gray Whales, during migration and summering); an age-based pattern (e.g., in Bison or Giraffe, where same-sex activity is more characteristic of younger animals, or in which the earlier years of an animal’s life are occupied largely with homosexual pursuits, to be followed by heterosexual activity in later years—or the reverse, as in some African Elephants); onetime “switches,” in which individuals change over from heterosexual to homosexual activity at a specific point in time (e.g., Herring Gulls, Humboldt Penguins), or from homosexual to heterosexual (e.g., Great Cormorants); as well as less structured sequencing, in which several periods of same-and opposite-sex activity of varying lengths may alternate with each other (e.g., Gorillas, Silver Gulls, King Penguins, Bicolored Antbirds).19

A group of male Walruses off the coast of Round Island (Alaska). Pairs of males are participating in courtship and other activities with each other while floating in the water. Male Walruses are often seasonally bisexual, engaging in homosexual pursuits outside the breeding season.

Simultaneous bisexuality also assumes many guises. At one extreme, sexual activity with same-sex and opposite-sex partners takes place at literally the same time: “pile-up” copulations, for example, in which a male mounts another male who is mounting a female (e.g., Wolves, Laughing Gulls, Little Blue Herons), or group sexual activity in which some or all participants are interacting with both males and females (e.g., Bonobos, West Indian Manatees, Common Murres, Sage Grouse). At the other extreme, individuals court or mate with both sexes separately, over short but relatively distinct spans of time, as in Crab-eating Macaques, Mountain Goats, Redshanks, and Anna’s Hummingbirds. In between these extremes are other patterns, such as ongoing bisexual trios and quartets, in which both same-sex and opposite-sex partners are bonded to one another concurrently (e.g., Greylag Geese, Oystercatchers, Jackdaws). Another form of simultaneity involves an animal in a pair-bond with a member of the opposite sex who has occasional courtship and/or sexual encounters with a member of the same sex (or vice versa). For example, male Herring and Laughing Gulls, Herons, Swallows, and Common Murres who have female partners, and female Mallard Ducks who have male partners, sometimes mount birds of the same sex. Conversely, female Snow Geese, Western Gulls, and Caspian Terns and male Humboldt Penguins and Laughing Gulls who have same-sex partners sometimes mate with opposite-sex partners. Still another variation is found in Lesser Flamingos: males in homosexual pairs sometimes try to mate with females who are themselves in homosexual pairs. And in some animals such as Bottlenose Dolphins, Black-headed Gulls, and Galahs, the combinations are even more varied: different forms of sequential and simultaneous bisexuality, as well as exclusive homosexuality (and heterosexuality) are found in different individuals within the same species and may even combine in the same individual at different points in time.

Even within a given category of bisexuality—say, simultaneous bisexuality involving interspersed homosexual and heterosexual activity—each individual within a population generally exhibits a unique sexual orientation profile, consisting of his or her own particular combination of same- and opposite-sex activity. The concept of a scale or continuum as developed by Alfred Kinsey for describing human sexual orientation is useful here: within each species, individuals generally fall along a range from those exhibiting predominantly or exclusively heterosexual behavior, to those exhibiting a balance of both, to those exhibiting predominantly or exclusively homosexual behavior, and every variation in between.20 Species as a whole also differ as to where the majority of individuals fall along this continuum, and how many engage in more exclusive homosexuality or heterosexuality as opposed to more equal bisexuality. Thus, among Bonobos every female participates in both homosexual and heterosexual activity, but the proportion of same-sex behavior exhibited by each of the females in one particular troop varied between 33 percent and 88 percent (averaging 64 percent); in female Red Deer, from 0–100 percent (averaging 49 percent); among Bonnet Macaque males, between 12 percent and 59 percent (averaging 28 percent); in male Pig-tailed Macaques, from 6–22 percent (averaging 18 percent); and among Kob females, from 1–58 percent (averaging 11 percent).21 In other words, within an overall pattern of bisexuality, individual animals exhibit varying “degrees” of bisexuality—different “preferences,” as it were, for homosexual as opposed to heterosexual activity.

These findings are particularly relevant since the concept of a scale or continuum of (homo)sexual behavior and orientation is yet another example of something still thought to be “uniquely human.” The Bonobo data (as well as that for the other species) directly refute one primatologist’s recent claim that “all wild primates we have seen within a particular species are equally homosexual …. If you lined up ten female bonobos, it’s not like one would be a 6 on the Kinsey scale and another a 2. They would all be the same number. It’s only humans who adopt identities.” 22 Of course, the Kinsey scale is specifically a measure of behaviors and not identities (it was designed expressly to bypass the often problematic issue of people’s “self-identification”), and certainly no animal studies purport to assess anything as subjective as sexual “identity.” In its intended usage, though, the Kinsey scale (or a comparable measure of sexual gradations) in fact appears to be particularly apt for Bonobos. The figures cited above are based on the work of Dr. Gen’ichi Idani in Congo (Zaire), who studied a troop consisting of (coincidentally) exactly ten female Bonobos and tabulated all their homosexual genital rubbings versus heterosexual copulations over a three-month period. The percentages of homosexual activity in these individuals were 33, 36, 47, 68, 68, 70, 75, 75, 82, and 88 percent. Idani also tabulated the number of different male and female partners of each female (another possible measure of degree of bisexuality or behavioral “preference”). Again, the percentage of partners that were same-sex exhibits a range across all females: 36, 50, 50, 54, 67, 67, 67, 69, 71, and 80 percent. Clearly these individuals fall into a spectrum in terms of their sexual behavior and thus exhibit different degrees of bisexuality in terms of their sexual orientation (although none are in fact exclusively heterosexual or homosexual).23

“Preference” for same-sex activity is, admittedly, a rather elusive concept to measure when dealing with nonhumans (though not nearly as slippery as “identity”). Although we cannot access their internal motivations or “desires,” animals do offer a number of other clues as to their individual “preferences” in addition to the proportion of their behaviors or partners that are same-sex. These include homosexual activity being performed in (spite of) the presence of members of the opposite sex, individuals actively competing for the attentions of same-sex partners (rather than “resorting” to such activity), advances of opposite-sex partners being ignored and/or refused, and “widowed” or “divorced” individuals continuing to pair with same-sex partners after the loss of a homosexual mate (even when opposite-sex partners are available). These types of behaviors have in fact been reported in more than 50 mammals and birds (see the profiles for some examples), indicating that for at least some individuals in these species, same-sex activity has “priority” over opposite-sex activity in some contexts. The converse is also true for species such as Canada Geese, Silver Gulls, Bicolored Antbirds, Jackdaws, and Galahs: in situations where opposite-sex partners are not available, only a fraction of the population engages in same-sex activity, indicating more of a heterosexual “preference” in the remainder of the population.24 Animals who do participate in same-sex activity in such a situational context could perhaps be said to exhibit a “latent” bisexuality; i.e., a predominantly heterosexual orientation with the potential to relate homosexually under certain circumstances. Another factor to be considered when evaluating individual “preferences” or degrees of bisexuality is the consensuality of the sexual interaction. Female Canada Geese and Silver Gulls in homosexual pairs, for example, may engage in occasional heterosexual copulations under duress; i.e., they are sometimes forcibly mated or raped by males. Likewise, heterosexually paired males in Common Murres, Laysan Albatrosses, Cliff Swallows, and several Gull species may be forcibly mounted by other males. Technically, all such individuals are “bisexual” because they engage in both homosexual and heterosexual activity, but the sort of bisexuality they exhibit is far different from that of a female Bonobo or a male Walrus, for instance, who willingly mates with animals of both sexes.

Broad patterns of sexual orientation across individuals show almost as much variation as that within individuals. In some species, the majority of animals are exclusively heterosexual, but a small proportion engage in bisexual activities (e.g., Mule Deer) or exclusively homosexual activities (e.g., male Ostriches). In others, the vast majority of individuals are bisexual and few if any are exclusively heterosexual or homosexual (e.g., Bonobos). Other species combine a pattern of nearly universal bisexuality with some exclusive homosexuality (e.g., male Mountain Sheep). In still other cases, the proportions are more equally distributed, but still vary considerably. In Silver Gulls, for instance, 10 percent of females are exclusively homosexual during their lives, 11 percent are bisexual, and 79 percent are heterosexual. Homosexual-bisexual-heterosexual splits for specific populations of other species include: 22-15-63 percent for Black-headed Gulls; 9-56-35 percent for Japanese Macaques; and 44-11-44 percent for Galahs.25

Thus, sexual orientation has multiple dimensions—social, behavioral, chronological, and individual—which must all be taken into account when assessing patterns of heterosexual and homosexual involvement. It is true that exclusive homosexuality in animals is less common than bisexuality—but it is not a uniquely human phenomenon, for it occurs in many more species than previously supposed. Moreover, because of the wide prevalence of bisexuality—both within and across species—exclusive heterosexuality is also certainly less than ubiquitous. Animals, like people, have complex life histories that involve a wide spectrum of sexual orientations, with many different degrees of participation in both same- and opposite-sex activities. To the question “Do animals engage in bisexuality or exclusive homosexuality?” we must therefore answer “both and neither.” There is no such thing as a single type of “bisexuality” nor a uniform pattern of “exclusive homosexuality.” Multiple shades of sexual orientation are found throughout the animal world—sometimes coexisting in the same species or even the same individual—forming part of a much larger spectrum of sexual variance.

|

|

|

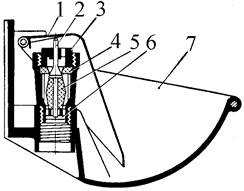

Кормораздатчик мобильный электрифицированный: схема и процесс работы устройства...

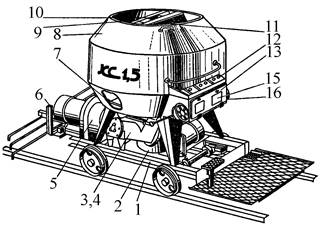

Автоматическое растормаживание колес: Тормозные устройства колес предназначены для уменьшения длины пробега и улучшения маневрирования ВС при...

Индивидуальные очистные сооружения: К классу индивидуальных очистных сооружений относят сооружения, пропускная способность которых...

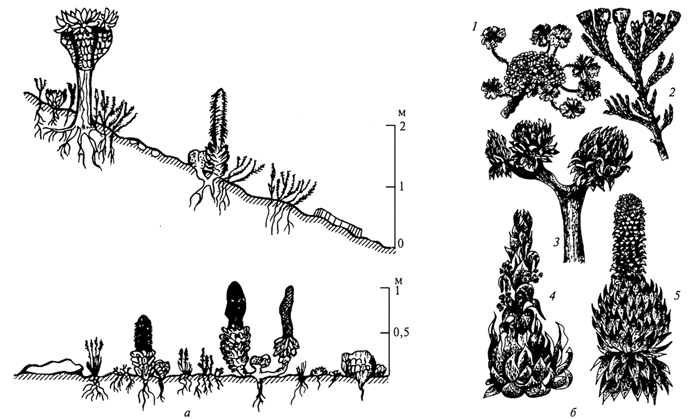

Адаптации растений и животных к жизни в горах: Большое значение для жизни организмов в горах имеют степень расчленения, крутизна и экспозиционные различия склонов...

© cyberpedia.su 2017-2025 - Не является автором материалов. Исключительное право сохранено за автором текста.

Если вы не хотите, чтобы данный материал был у нас на сайте, перейдите по ссылке: Нарушение авторских прав. Мы поможем в написании вашей работы!