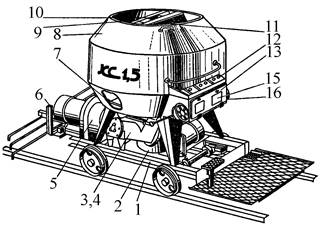

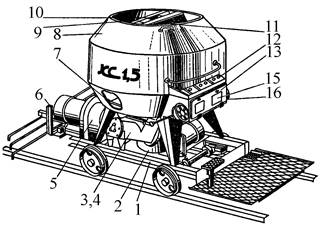

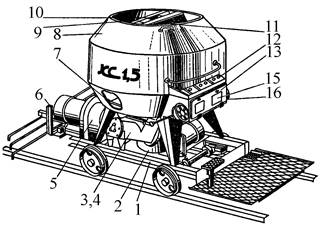

Кормораздатчик мобильный электрифицированный: схема и процесс работы устройства...

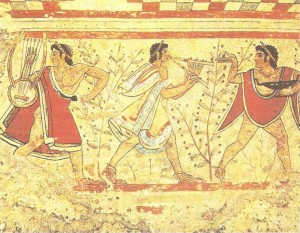

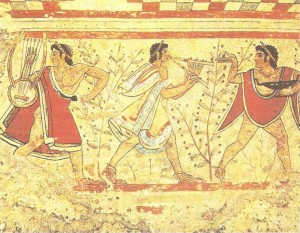

Археология об основании Рима: Новые раскопки проясняют и такой острый дискуссионный вопрос, как дата самого возникновения Рима...

Кормораздатчик мобильный электрифицированный: схема и процесс работы устройства...

Археология об основании Рима: Новые раскопки проясняют и такой острый дискуссионный вопрос, как дата самого возникновения Рима...

Топ:

Установка замедленного коксования: Чем выше температура и ниже давление, тем место разрыва углеродной цепи всё больше смещается к её концу и значительно возрастает...

Характеристика АТП и сварочно-жестяницкого участка: Транспорт в настоящее время является одной из важнейших отраслей народного хозяйства...

Теоретическая значимость работы: Описание теоретической значимости (ценности) результатов исследования должно присутствовать во введении...

Интересное:

Средства для ингаляционного наркоза: Наркоз наступает в результате вдыхания (ингаляции) средств, которое осуществляют или с помощью маски...

Уполаживание и террасирование склонов: Если глубина оврага более 5 м необходимо устройство берм. Варианты использования оврагов для градостроительных целей...

Финансовый рынок и его значение в управлении денежными потоками на современном этапе: любому предприятию для расширения производства и увеличения прибыли нужны...

Дисциплины:

|

из

5.00

|

Заказать работу |

Содержание книги

Поиск на нашем сайте

|

|

|

|

From a distance this might be mistaken for fighting, but perverted sexuality is the real keynote …. In fact, the birds seem sometimes hardly to understand themselves, or to know where their feelings are leading them …. My principal observation during the earlier part of the time … was a repetition of what I have before noted in regard to the sexual perversion, as one calls it—a term which serves to save one the trouble of thinking ….

—from a scientific description of Ruffs in 1906

Three unnatural tending bonds were observed: … On July 16 a two-year-old bull closely tended a yearling bull for at least four hours in the Wichita Refuge and attempted mounting with penis unsheathed ….

—from a scientific description of American Bison in 1958

Among aberrant sexual behaviors, anoestrous does were very occasionally seen to mount one another ….

—from a scientific description of Waterbuck in 198214

In many ways, the treatment of animal homosexuality in the scientific discourse has closely paralleled the discussion of human homosexuality in society at large. Homosexuality in both animals and people has been considered, at various times, to be a pathological condition; a social aberration; an “immoral,” “sinful,” or “criminal” perversion; an artificial product of confinement or the unavailability of the opposite sex; a reversal or “inversion” of heterosexual “roles”; a “phase” that younger animals go through on the path to heterosexuality; an imperfect imitation of heterosexuality; an exceptional but unimportant activity; a useless and puzzling curiosity; and a functional behavior that “stimulates” or “contributes to” heterosexuality. In many other respects, however, the outright hostility toward animal homosexuality has transcended all historical trends. One need only look at the litany of derogatory terms, which have remained essentially constant from the late 1800s to the present day, used to describe this behavior: words such as strange, bizarre, perverse, aberrant, deviant, abnormal, anomalous, and unnatural have all been used routinely in “objective” scientific descriptions of the phenomenon and continue to be used (one of the most recent examples is from 1997). In addition, heterosexual behavior is consistently defined in numerous scientific accounts as “normal” in contrast to homosexual activity.15

The entire history of ideas about, and attitudes toward, homosexuality is encapsulated in the titles of zoological articles (or book chapters) on the subject through the ages: “Sexual Perversion in Male Beetles” (1896), “Sexual Inversion in Animals” (1908), “Disturbances of the Sexual Sense [in Baboons]” (1922), “Pseudomale Behavior in a Female Bengalee [a domesticated finch]” (1957), “Aberrant Sexual Behavior in the South African Ostrich” (1972), “Abnormal Sexual Behavior of Confined Female Hemichienus auritus syriacus [Long-eared Hedgehogs]” (1981), “Pseudocopulation in Nature in a Unisexual Whiptail Lizard” (1991).16 The prize, though, surely has to go to W. J. Tennent, who in 1987 published an article entitled “A Note on the Apparent Lowering of Moral Standards in the Lepidoptera.” In this unintentionally revealing report, the author describes the homosexual mating of Mazarine Blue butterflies in the Atlas Mountains of Morocco. The entomologist’s behavioral observations, however, are prefaced with a lament: “It is a sad sign of our times that the National newspapers are all too often packed with the lurid details of declining moral standards and of horrific sexual offences committed by our fellow Homo sapiens; perhaps it is also a sign of the times that the entomological literature appears of late to be heading in a similar direction.”17 Declining moral standards—in butterflies?! Remember, these are descriptions by scientists in respected scholarly publications of phenomena occurring in nature!

In addition to such labels as unnatural, abnormal, and perverse, a variety of other negative (or less than impartial) designations have also been employed in the scientific literature. Once again, these span the decades. Mounting among Domestic Bulls is characterized as a “male homosexual vice” (1983), echoing a description from nearly a century earlier in which same-sex activities between male Elephants are classified as “vices” and “crimes of sexuality” that are “prohibited by the rules of at least one Christian denomination” (1892). Courtship and mounting between male Lions is called an “atypical sexual fixation” (1942); same-sex relations in Buff-breasted Sandpipers are described in an article on “sexual nonsense” in this species (1989); while courtship and mounting between female Domestic Turkeys are referred to as “defects in sexual behavior” (1955). Homosexual activities in Spinner Dolphins (1984), Killer Whales (1992), Caribou (1974), and Adélie Penguins (1998) are characterized as “inappropriate” (or as being directed toward “inappropriate” partners), and same-sex courtship among Black-billed Magpies (1979) and Guianan Cock-of-the-Rock (1985) is called “misdirected.” In what is perhaps the most oblique designation, one scientist uses the term heteroclite (meaning “irregular” or “deviant”) to refer to Sage Grouse engaging in homosexual courtship or copulations (1942).18

Besides labeling same-sex behavior with derogatory or biased terms, many scientists have felt the need to embellish their descriptions of homosexuality with other sorts of value judgments. Repeatedly referring to same-sex activity in female Long-eared Hedgehogs as “abnormal,” for example, one zoologist matter-of-factly reported that he separated the two females he was studying for fear that they might actually “suffer damage” from continuing to engage in this behavior. Similarly, in describing pairs of female Eastern Gray Kangaroos, another scientist suggested that only in cases where there was no (overt) homosexual behavior between the females could bonding be considered to represent a “positive relationship between the two animals.” In the 1930s, homosexual pairing in Black-crowned Night Herons was labeled a “real danger,” while one biologist (upon learning the true sex of the birds) referred to his discovery and reporting of same-sex activities in King Penguins as “regrettable disclosures” and “damaging admissions” about “disturbing” activities. More than 50 years later, a scientist suggested that homosexual behavior between male Gorillas in zoos would be “disturbing to the public” were it not for the fact that people would be unable to distinguish it from “normal heterosexual mating behavior.” Same-sex pairing in Lorikeets has been described as an “unfortunate” occurrence, while mounting activity between female Red Foxes has been characterized as being part of a “Rabelaisian mood.” Finally, in describing the behavior of Greenshanks, an ornithologist used unabashedly florid and sympathetic language to characterize an episode of heterosexual copulation, referring to it as a “lovely act of mating” and concluding, “The grace, movement, and passion of this mating had created a poem of ecstasy and delight.” In contrast, homosexual copulations in the same species were given only cursory descriptions, and one episode was even characterized as a “bizarre affair.”19

In a direct carryover from attitudes toward human homosexuality, same-sex activity is routinely described as being “forced” on other animals when there is no evidence that it is, and a whole range of “distressful” emotions are projected onto the individual who experiences such “unwanted advances.”20 One scientist surmises that Mountain Sheep rams “deem it an insult to be treated as a female” (including being mounted by another male), while Rhesus Macaques and Laughing Gulls are described as “submitting” to homosexual mounts even when there is clear evidence that they are willing participants (for example, by initiating the activity). Cattle Egrets who are mounted during homosexual copulations are characterized as “suffering males,” while female Sage Grouse mounted by other females are their “victims.” Orang-utan males who participate in homosexuality are said to be “forced into nonconformist sexual behavior” by their partners even though they display none of the obvious signs of distress (such as screaming and struggling violently) that are characteristic of female Orangs during heterosexual rapes. Scientists describing same-sex courtship in Kob antelopes imply that females try to “avoid” homosexual attentions by circling around the other female or butting her on the shoulder. In fact, these actions are a formally recognized ritual behavior called mating-circling that is a routine part of heterosexual courtships, and not indicative of disinterest or “unwillingness” on the part of the courted female. Females who do not want to be mounted (by male partners) actually drop their hindquarters to the ground (a behavior not observed in homosexual contexts). Same-sex courtship in Ostriches is deemed to be a “nuisance” that goes “on and on” and is perpetrated by “sexually aberrant” males. The calm stance of a courted male (referred to as the “normal” partner) in the face of such homosexual advances is described as “astonishing,” while the recipient’s occasional acknowledgment of the activity is downplayed in favor of those times when he makes no visible response (interpreted as disinterest). Yearling male Guianan Cock-of-the-Rock are consistently described as “taking advantage of” or “victimizing” adult males that they mount, while their partners are said to “tolerate” such homosexual activity. This is at odds with the descriptions, by the same scientists, of the adult partners as willing participants who actively facilitate genital contact during homosexual mounts and allow the yearlings to remain on their territories (unlike unwanted adult intruders who are chased away or attacked). Finally, male Mallard Ducks that switch from heterosexual to homosexual pairings are described as being “seduced” by other males, while Rhesus Macaques are characterized as reacting with a sort of “homosexual panic” to same-sex advances—both echoing widely held misconceptions about human homosexuality.21

In other cases, zoologists have problematized homosexual activity or imputed an inherent inadequacy, instability, or incompetence to same-sex relations, when the supporting evidence for this is scanty or questionable at best and nonexistent at worst. For example, the fact that male homosexual pairs in Greylag Geese engage in higher rates of pair-bonding and courtship behavior is ascribed to an (unsubstantiated) “instability” of same-sex pair-bonds. In fact gander pairs in this species have been documented as lasting for 15 or more years and are described as being, in many cases, more strongly bonded than heterosexual mates.22 Similarly, even though pair-bonds between male Ocellated Antbirds can last for years, one ornithologist insisted on portraying them as “fragile” and liable to dissolve at the mere appearance of a “nubile female.” Antbird same-sex pairs do sometimes divorce, but so do heterosexual ones, and any generalizations about the comparative stability of each cannot be made without comprehensive, long-term studies of pair-bonding—which have yet to be undertaken for this species.23 The fact that sexual activity between female Gorillas generally takes longer than heterosexual copulations is speculatively attributed to “mechanical difficulties” involved in sex between two females—it is apparently inconceivable to the investigator that females might be experiencing closer bonding or greater enjoyment with each other (as reflected by their face-to-face position and other features that also distinguish homosexual from heterosexual activity in this species). In the same vein, accounts of same-sex mounting in Western Gulls, Guianan Cock-of-the-Rock, and Red Foxes refer to the “disoriented,” “bumbling,” or “fumbling” actions of some individuals—terms that are rarely used to describe nonstandard mounting attempts in heterosexual contexts (even when they are equally “incompetent”). Conversely, one primatologist is willing to concede that affiliative gestures (such as mutual touching, grooming, or preening) between animals of the opposite sex may be “tender” and even “an expression of love and affection,” yet similar or identical activities between same-sex participants are never characterized this way.24

This double standard is particularly apparent where descriptions of same-sex pairs in Gulls are concerned. When a male Laughing Gull in a homosexual pair courted and mounted a female, for example, this was taken by one investigator to mean that his pair-bond was unstable and that he was “dissatisfied” with his homosexual partnership (rather than as simply an instance of bisexual behavior). In contrast, homosexual activity by birds in heterosexual pairs is never interpreted as “dissatisfaction” with heterosexuality or as reflecting the tenuousness of opposite-sex bonds. In a study on pair-bonding in Black-headed Gulls, the term “monogamous” (implying stability) was reserved for heterosexual pairs, even though homosexual pairs in this species can also be stable and monogamous, and heterosexual pairs are sometimes nonmonogamous. Likewise, the stability of female pairs of Herring Gulls was claimed to be lower than heterosexual pairs. Yet in making this assessment, researchers were considering females to have broken their pair-bond if they were simply not seen at the nesting colony the following year—when in fact they or their partner could have died, relocated, or been missed by observers. Among those females that were subsequently observed at the colony (a more accurate measure, and the standard way of calculating mate fidelity for heterosexual pairs), the rate of pair stability was in fact nearly identical to that of opposite-sex pairs.

Similarly, the parenting abilities of female pairs in many Gull species are often implied to be substandard because such couples usually hatch fewer chicks than heterosexual pairs. However, calculations of the hatching success of homosexual pairs typically include infertile eggs in the overall count; since many females in same-sex pairs do not mate with males, large numbers of their eggs are infertile and so of course a larger proportion of their clutches do not hatch. In addition, all of the traits taken to indicate poor quality of parenting in some female pairs—e.g., smaller eggs, slower embryonic development, lower hatching rate of fertile eggs, reduced weight and greater mortality of chicks, higher rates of loss or abandonment—are also characteristic of supernormal clutches attended by heterosexual parents (usually polygamous trios). In other words, they are related to the larger-than-average clutch size rather than the sex of the parents per se. In fact, most studies of Gulls have shown that the parenting abilities of homosexual pairs are at least as good as those of heterosexual pairs. Moreover, heterosexual parents in many Gull species can be severely neglectful or overtly violent toward their chicks, causing youngsters to “run away” from their own families and be adopted by others (or even perish). Needless to say, this behavior is never interpreted as being representative of all heterosexual pairs or as impugning heterosexuality in general (even though it is usually far more widespread than homosexual inadequacies).25 Thus, many zoological studies evidence the same inconsistency often found in discussions of human homosexuality: any difficulties or irregularities in same-sex relations are generalized to all homosexual interactions (or else focused on to the exclusion of other examples), whereas comparable problems in opposite-sex relations are seen in the proper perspective, simply for what they are—individual (or idiosyncratic) occurrences that, while noteworthy, do not reflect the entirety of heterosexuality nor warrant disproportionate attention.

Homophobia in the field of zoology is not always this overt or virulent; nevertheless, ignorance or negative attitudes that are not directly expressed usually have identifiable consequences and important ramifications for the way the subject is handled. Discussion of animal homosexuality has in fact been compromised and stifled in the scientific discourse in four principal ways: presumption of heterosexuality, terminological denials of homosexual activity, inadequate or inconsistent coverage, and omission or suppression of information.

|

|

|

Папиллярные узоры пальцев рук - маркер спортивных способностей: дерматоглифические признаки формируются на 3-5 месяце беременности, не изменяются в течение жизни...

История развития хранилищ для нефти: Первые склады нефти появились в XVII веке. Они представляли собой землянные ямы-амбара глубиной 4…5 м...

Биохимия спиртового брожения: Основу технологии получения пива составляет спиртовое брожение, - при котором сахар превращается...

Кормораздатчик мобильный электрифицированный: схема и процесс работы устройства...

© cyberpedia.su 2017-2025 - Не является автором материалов. Исключительное право сохранено за автором текста.

Если вы не хотите, чтобы данный материал был у нас на сайте, перейдите по ссылке: Нарушение авторских прав. Мы поможем в написании вашей работы!