The culture of Achaemenid Persia drew from many sources. Its character was especially dependent on the Assyrian and Babylonian influences that preceded it. The king held absolute authority, and all the land of the empire was his. When someone approached his throne, he or she had to prostrate before him. When speaking, subjects covered their mouth lest the monarch breathe "contaminated" air. The two capitals, Persepolis and Susa, were crowded with artisans and artists to decorate the palaces of the rulers with sculpture and painting to glorify their master.

The kings, who bore the title shahinshah, the Medean King of Kings, ruled their empires in the tradition of Cyrus. This meant that local language and culture continued as long as taxes were paid. Over all the empire there was a single standard of weights and measures, and a small gold coin, the daric, was used for currency. The Persian king's law, however, was supreme, supplanting all other local legal systems. For practical purposes, the law was written in Aramaic, so that the many Semitic peoples of the empire could read it.

A large bureaucracy served the Persian king, whose duties were to enforce the ruler's justice, to keep domestic order, and to collect the taxes that supported the army from the 20 satrapies or provinces. The taxes were collected in coin rather than goods, for the empire's daric was accepted everywhere within Persian borders.

Much of the monies that came to the kings supported the huge armies, which they kept for their campaigns. This imperial force held contingents from all the empire's peoples, from India to Egypt. To move their soldiers efficiently, the kings built a Royal Road that traversed the empire for 1,600 miles, from Susa to Sardis in Anatolia. Couriers on horseback made the journey in seven days.

The religion of the Achaemenids, Mazdaism, was based on the worship of a supreme deity named Ahura Mazda. Other Persian deities included Mithra, the sun god, and Anahita, a fertility divinity.

Worship was in temples where a fire was kept burning to symbolize the presence of Ahura Mazda. Keepers of the fire were the magi, a hereditary class of priests. One of Mazdaist teachings forbade either burial or cremation, since it mispolluted the earth or fire. Therefore the dead were exposed, to be consumed by scavenger birds.

Some authorities believe that a prophet, Zarathushtra (Zoroaster), in the early sixth century ВС first introduced Mazdaism into Persia. Little is known for certain of Zarathushtra, but he is credited with writing about 570 ВС the first hymns that now are found in the Avesta, the scriptures of the Mazdaists. The religion is sometimes known as Zoroastrianism in honor of its prophet. Mazdaism also contained a dualistic concept of the divinity. It held that the cosmos was constantly a scene of combat between good and evil, between Ahura Mazda and the wicked divinity, Ahriman, who sought to win over the world of humanity to destruction. After death men and women faced judgment, the good going to a place of bliss and the evil to a fiery pit.

EGYPT

Nile Valley

Once the mighty Nile, a river 4,100 miles long, carried a much greater volume of water than it does today. On its way to the Mediterranean, it hollowed out a trench 600 miles long and 30 miles wide through the limestone plateau that makes up northern Africa. Progressively the climate grew drier until, in historic times, the Nile retreated to its present state in Egypt.

The land adjacent to the southern Nile was called Upper Egypt. Where it enters the Mediterranean, the river created a huge delta, a marsh full of weeds and rushes, but the delta was extremely fertile once it was cultivated. This was Lower Egypt. Egyptians were always aware of the differences between the two regions of Upper and Lower Egypt. They called their country "the two lands."

On its descent from the African interior, the Nile passes through six cataracts, rapids where the water rushes over rocks preventing navigation.

The first is at Aswan, now the site of a great dam and Lake Nasser, whichwas built to control the flow of water year round. In ancient times, during the annual summer flood, the Nile rose 25 to 26 feet, covering the land with a half inch overcoat of fertile mud. Much of the water remained in natural pools along the Nile.

The climate of the Nile Valley, so dry and practically without rain, is excellent for preserving artifacts and written materials. For this reason archaeologists know a great deal about ancient times in Upper Egypt. They have discovered an immense treasure in Egyptian tombs. In addition, since the ancient Egyptians had their own type of writing on monuments, called hieroglyphs, a continuous story of the life of ancient Egypt can be recorded.

Even though the knowledge of how to read hieroglyphs was lost during the Middle Ages, in AD 1799 the discovery of the Rosetta Stone made it possible to read them once again. The Rosetta Stone contained an inscription written in hieroglyphs, demotic Egyptian, and Greek. By comparing the three scripts, Jean-Francois Champollion broke the code that held the mystery of hieroglyphic writing.

Earliest Egypt

Ancient villages of Neolithic peoples are found throughout Egypt. Their tombs provide a rich assortment of grave gifts. About 3600 ВС the skulls in the graves change, from narrow-faced people to those with broad foreheads. The broad-headed men and women brought plants from Asia, including flax and cotton, giving a hint of their origin. They began the reclamation of land along the Nile, clearing the marshes and building canals for drainage. They also built boats. From them they fished and caught birds in the marshes created by the Nile to supplement their diets.

Farming in Egypt was easier than in Mesopotamia for the flood came before planting rather than at the time of harvest as in the Tigris-Euphrates Valley. Egyptian peasants did not need the elaborate irrigation system of their neighbors to the north for it required little labor to tap into the pools of water left after the flood.

Arts of Egypt

The Egyptians were anxious to take whatever was of value from their neighbors in Mesopotamia. They learned to make cylinder seals, to use brick for paneling and decoration, and most importantly, to use writing. The Egyptians kept their own gods and goddesses, however, and did not attempt to build any ziggurats.

As the population increased and the cultivated land extended farther from the Nile, the haphazard method of farming appeared more and more inefficient. Although there are no details, some village chiefs must have attempted greater control over water distribution. Little by little, larger and more important regions swallowed their smaller neighbors. At last there were but two dynasties, one in Upper Egypt and the other in Lower Egypt. (A dynasty is composed of rulers who succeed each other because of heredity.)

Tradition tells that the unification of the two regions of the country took place about 3100 ВС under King Narmer of Abydos of Upper Egypt. He is given credit for uniting the two lands of Upper and Lower Egypt, thus assuming the title of pharaoh, which means Great House. There is also an iconographic proof of the unification - a palette that shows the pharaoh defeating his enemies while wearing a double crown, symbolic of the unification. Pharaoh's rule of the two lands was visibly portrayed by his wearing the red crown of Lower Egypt and the white crown of Upper Egypt. Egypt of the Old Kingdom was wealthy enough to support a large class of artisans and artists, in addition to those who worked on the tombs. Early on, these artists determined certain styles that were to last for the next 3,000 years. The conservative spirit of the Egyptians is best demonstrated in its art. For example, the painted human figure always has the face in profile, and the legs and shoulders bent forward. Statues of the pharaoh  and his wife always have their eyes fixed, godlike, on the horizon. One foot is in front of the other. Facial expressions are always grim, as befit those with such heavy responsibilities that a whole kingdom depended on their will.

and his wife always have their eyes fixed, godlike, on the horizon. One foot is in front of the other. Facial expressions are always grim, as befit those with such heavy responsibilities that a whole kingdom depended on their will.

The extant architecture of ancient Egypt is confined to tombs and temples because they were built in stone. The obvious skill in planning and erecting them proves that the Egyptians far surpassed all other ancient civilizations in these areas.

Glass was an Egyptian invention, and its production extended from small perfume bottles to large vases. The Egyptians loved to carve in stone, as evidenced by numerous artifacts that survive. Hieroglyphic writing covers Egyptian monuments, each figure chiseled with great care. Carpenters approached the level of sculptors in their skillful decoration of furniture.

Egypt's neighbors always were impressed with the kingdom's many doctors. Sick people who sought healing in the ancient Mediterranean region journeyed to Egypt for cures.

The skill of the Egyptian doctors is closely related to their knowledge of human anatomy gained from the universal desire of Egyptians to be mummified at the time of their death. This required an elaborate ritual as well as dissection in order to remove those organs of the body that could be expected to hasten decay. As a result, Egyptian doctors knew more about the body than any other ancient people - how to use surgery, set bones, and even operate on the brain.

It was the Egyptians who developed the solar calendar, assigning 30 days to 12 months. At the close of the year, adding an extra 5 days kept the calendar up to date. Three seasons were reckoned according to the Nile's position: before, during, and after the flood.

Old Kingdom

Narmer's capital was at Memphis, located very near modern Cairo. It was at the juncture of the Delta and Upper Egypt, allowing him and his successors to keep a watchful eye on both parts of his kingdom, for separatism was still a factor. His realm was basically a land of villages rather than large cities. Those towns that did exist were administrative centers or religious sites.

Once established, Egyptian life lent itself to centralization. To supervise the irrigation of the land and to oversee the storage of the grain crop was essential to avoid famine, the greatest threat to the growing Egyptian population of

about 4,000,000 people. Rebellions and revolutions severely disturbed the serenity that dominated the consciousness of the average Egyptian.

The Old Kingdom is that period of history that dates from about 2770 to 2200 ВС. During that time it has been customary to trace the several dynasties that held power. Later periods are known as the Middle and finally the New Kingdom, or Empire.

Egypt's unique rule of a single individual over hundreds of square miles received further confirmation when the pharaoh, or his advisors, came up with the idea that he must be a god. Whether the pharaoh believed this himself is unknown, but in their search for security the men and women of Egypt apparently accepted this view of him. It was a very consoling thought that one of the gods, not an ordinary human, guided the destiny of the nation and kept the world from falling back into chaos.

Egypt in contrast to Mesopotamia, had very few law codes, since it was always possible to appeal to the living god. In Egypt the pharaoh's will was divine law.

Pharaoh could be any god that he wanted. One tomb text has it, "What is the King of Upper and Lower Egypt? He is a god by whose dealings one lives, the father and mother of all men alone, by himself, without equal." During the Old Kingdom he alone was immortal and therefore deserved a lavish funeral.

The notion that pharaoh was god obviously put him in a unique position in the nation's class structure. Most pharaohs kept large harems, where the queen mother ruled supreme. In their palaces they collected artifacts from all over the eastern Mediterranean, prestige goods that confirmed their importance.

The next step below the royal family consisted of the officials who served the pharaoh in multiple ways. The most important was an official who bore the titles Overseer of the Palace and Sealbearer of Lower Egypt.

All officials served at the pleasure of the pharaoh. They lived in spacious homes and to the extent possible filled them with expensive furniture. A garden and pool helped break the monotonous brown of the hot season.

Both men and women dressed in tightly woven cotton garments and decorated themselves in jewelry. Children wore no clothes at all until reaching 12 years of age. Egyptians used a wide range of cosmetics. People wore dark eye makeup under their eyes to deflect the sun's glare. At banquets women put perfumed cones on their heads that melted as the evening progressed, giving off a pleasant odor.

Wives generally were given an equal status with their husbands. They conducted their own businesses and owned land in their own names, but they were denied entry into the class of administrators. In case of divorce, one third of the property went to the wife.

Titled office holders proliferated during the fifth and sixth dynasties. On the walls of their tombs, they were careful to make sure that their importance was noted. Governors of outlying provinces did their part to be noticed in hopes of a promotion to court. Although pharaoh himself was a god, he had to share his divinity with a large group of other gods and goddesses in the Egyptian pantheon. Therefore, the priests and priestesses who served in the temples of these divinities held a special role paralleling that of the pharaoh's civil officials.

The Egyptian middle class, composed of lesser officials, private landowners, artisans, scribes, and army personnel, occupied their own niche. The vast majority of Egyptians, the peasant class, did not enjoy an easy life. Their day was spent from dawn to dusk working in the fields of their masters or watching over their animals. Pay was a scant portion of the harvest, hardly enough to feed their families.

The peasant's work — building canals, digging wells, sewing and reaping the crops — made Egypt wealthy. At times of high flood when the Nile crested 2 yards above normal, all the peasant's work was undone and had to be started over.

There were few slaves in Egypt, for in the Old Kingdom, military expeditions outside the country were infrequent. Without prisoners of war, a reservoir of slaves could not form. Men, women, and children of the peasant class worked together planting, tilling, and harvesting the crops.

Egypt depended on farming for its great wealth in the Old Kingdom. Trade outside Egypt was minimal, for the pharaoh's government kept a monopoly on what little export business existed. Scenes of farming, more than any other subject, are pictured on tomb walls.

New Kingdom

Ahmose learned from the Hyksos how to use the weapons that they had introduced into Egypt. What he intended, once the Hyksos power was broken, was to make Egypt a military force that should be reckoned with in the future. Egyptian nobles were expected to fill his officer corps, and a standing army of recruits gave Egypt an opportunity to initiate a period of empire-building.

The result was a series of campaigns against Nubia in the south, now Sudan, and Palestine and Syria to the northeast. For the first time in history, an Egyptian army camped on the banks of the Euphrates.

About 1490 ВС an Egyptian woman ruled in her own name, but as a king, not a queen. Her statues show her wearing the ceremonial beard of the pharaohs. This was Hatshepsut, who was both the daughter of one pharaoh and the wife of another. The Egyptian royal family, contrary to the fear of incest in other cultures, favored marriage with close kin. Apparently this kept the royal blood from dilution.

Hatshepsut ruled efficiently, and several times personally led the army in combat. Her tomb at Deir el-Bahri is one of the New Kingdom's finest pieces of architecture. By the time of her death, pyramids were no longer in fashion.

Her son, Thotmes III, pharaoh from 1490 to 1468 ВС was constantly at war, for the Syrian border defied all efforts to make it stable. At Megid-do, the key fortress in Palestine, Thotmes won a great victory.

Religion

The ancient Egyptians believed the world was alive with supernatural beings that they could not see, along with the pharaoh whom they could see. About 80 major deities existed, each with a share of devotees. Hundreds of priests served in the temples that dotted the Egyptian countryside.

Among the major divinities were Horus, the falcon god; Thoth, represented by the ibis and baboon; and Anubis, who was a reclining jackal and later a human with a jackal's head. The goddess Hathor was pictured as a cow. The fact that the gods appeared so frequently as animals was special to Egypt. The Egyptians believed that there was a divine quality in animals. In a world where little changed from day to day, the Egyptians found confirmation in each new animal generation reproducing its parents.

In addition to the animal gods, there were cosmic ones. The sun, earth, sky, air, and water were all divine. Myths recounted their origins and history. Ra, the sun god, was the Creator, "Only after I came into being did all that was created come into being."

Each day Ra sailed across the sky in a boat. Then at night when he disappeared, he had to fight a battle with darkness to rise again. The priests in the temple at Heliopolis had to offer prayers on a daily basis to make sure that the sun would rise.

Other deities, Ptah and Khnum, were also creators. During the Middle Kingdom, the story of Osiris and Isis gained great popularity. The myth held that a wicked brother killed Osiris and cut up his body into many parts. Then Isis collected them and wrapped them up restoring him to immortal life. He then became judge of the underworld. After death, Osiris weighed the heart of a person on a scale with a feather. If it was too heavy from bad actions it was eaten, and the person was denied admittance into the land of the blessed.

In Thebes, the major city of Upper Egypt, the favorite god was Amon, pictured with a ram's head. He was the Hidden One, who gave the breath of life and caused the wind to blow. Later Ra was merged with Amon to become Amon-Ra and as a hybrid became the nation's supreme deity. Long hymns of praise to Amon - Ra give testimony to his popularity, especially at Thebes, which was the god's favored city.

One of the basic assumptions of the Egyptians, that the world was always the same, was challenged by death. This often came so quickly, sometimes violently, and made the Egyptians reconsider if they had their world view correct.

They believed that the cosmos was held together by a force known as ma'at. Although open to many translations, ma'at might be considered as the balance that provided right order. It governed the universe from the heavens to the earth, from plants to animals and humans. Even the Nile itself responded to ma'at.

Opposed to ma'at were ignorance, passion, pride, and anything else that upset the comfortable stability that enveloped the Egyptians. Death, of course, was the supreme contradiction. Therefore, it demanded great care and preparation, and consumed a large amount of the time of the living.

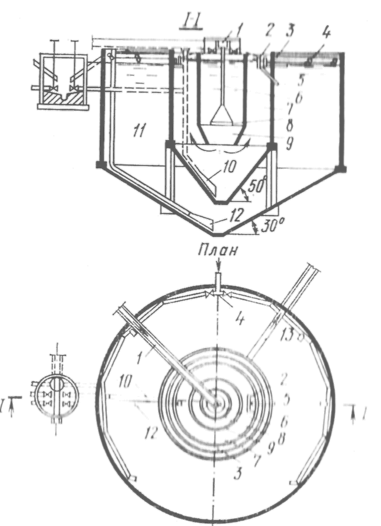

The first Old Kingdom tombs are called mastabas. They are found in two of Egypt's oldest sites, Abydos and Saqqara. The Egyptians probably borrowed the idea for their construction from Mesopotamian royal burials.

The first mastabas were brick and rectangular in shape, with sloping walls. A flat roof of cedar beams covered the ceiling. The Egyptians had plenty of stone, so rather than mud brick, later mastabas were made of stone shaped like brick.

During the fourth dynasty, from about 2560 to 2440 ВС, when the power of the pharaohs was at its peak, the mastaba became the pyramid. More than any verbal confirmation, the pyramid testified to the overwhelming power and majesty of the pharaohs. The first, called the step-pyramid, had Imhotep for its architect. He built it over 200 feet high, the first major stone building in world history, for his pharaoh Zoser.

and his wife always have their eyes fixed, godlike, on the horizon. One foot is in front of the other. Facial expressions are always grim, as befit those with such heavy responsibilities that a whole kingdom depended on their will.

and his wife always have their eyes fixed, godlike, on the horizon. One foot is in front of the other. Facial expressions are always grim, as befit those with such heavy responsibilities that a whole kingdom depended on their will.