One other way to think about your research questions is as a way of asking what you need to know in order to achieve your aim and objectives.

An aim is a general statement of intent or aspiration, for example:

- The project will transform Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) beacons into an innovative, low-cost and highly engaging interpretation option for listed buildings.

The objectives specify the steps you will take to achieve outcomes that contribute to your aim, for example:

- To produce BLE beacon-based applications for historic buildings;

- To develop methods for assessing visitor engagement with BLE beacon applications;

- To develop processes and tools for producing interpretive material for BLE applications; and

- To link the BLE beacon application with the rest of the historic building’s interpretive offer.

In articulating your objectives, opt for specific, measurable verbs, like ‘collect’, ‘construct’, ‘classify’, ‘develop’, ‘measure’, ‘produce’ or similar. Avoid vague verbs like ‘appreciate’, ‘consider’, ‘enquire’, ‘understand’, ‘be aware of’, ‘appreciate’ etc.

Answering your research questions will contribute to achieving your aims and objectives. Following the example above, your questions might include:

- What kinds of interpretive content is suitable for delivery via BLE beacon applications?

- How do visitors engage with a historic building and its history and how do available interpretive material and resources affect this engagement?

- How can we measure visitor engagement with a historic building and its history?

You can present the relationship between objectives and questions in two ways: you can either start with an objective and list underneath it the questions that you need to answer in order to achieve it; or you can start with a question and list underneath it the objectives that you need to achieve in order to answer it.

Thanks to Dr Giasemi Vavoula, School of Museum Studies for these approaches.

Write a research question

23 comments

Drawing on some of the approaches and ideas we have covered in the previous few steps, we would now like you to write an initial research question that captures the general nature of what you want to research. For example:

‘value chain management in the telecoms sector’,

‘micro-finance in Ghana’,

‘school leadership in further education’.

Note down at least one process that is present in the setting you are interested in. For example,

‘negotiating contracts’,

‘evaluating applicants’,

‘devising workload models’.

For each process, outline the various steps that are involved, the stakeholders who have a role or are affected by the process, and any problems that may emerge at each point. Consider what you have learned about reflexive reviews and apply this to your development of the research question.

Revise your initial question so that it is focused on the interaction between stakeholders and specific points in the process you have outlined. For example,

‘arranging tenders from key suppliers’,

‘filling in forms with uncertain information’.

Try to make your question as narrow as possible. Repeat this at least ten times, starting each time with the initial general question. You will now have a very general topic with a series of very focused questions. However, your actual research questions ought to lie somewhere in the middle. Try to place the ten specific questions into between three to five more general questions – these will be the basis for your actual research questions.

Share your progress with your fellow learners, and use the discussion area to give feedback on each other’s outcomes.

Reflexive review

11 comments

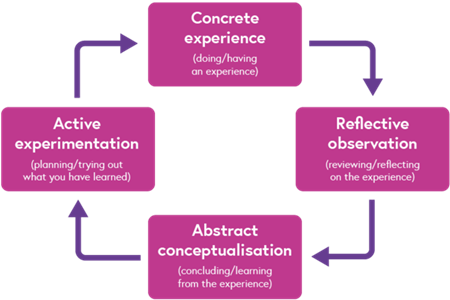

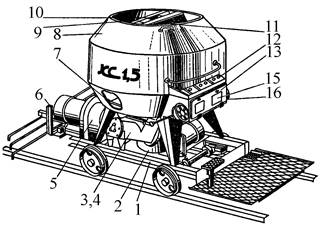

Once you have undertaken the previous exercise and have written a draft research question, as is the case with any text you will write, it is time to reflect and edit. In fact, according to Becker (1986), academics undertake far more editing and re-writing than actual writing. (Many a colleague at the University of Leicester will admit to this! Almost no one can write a ‘polished’ text in one go!). Personal experience of both a research issue and of writing about it is very important to defining a good research problem. A well-known model developed by Kolb (1984), shown above, demonstrates this well.

In Kolb’s model, learning typically starts when we encounter a problem or difficulty – a ‘concrete experience’. This kind of experience is particularly striking or remarkable. For example, this could take the form of a breakdown in communication between two groups who had previously had good relations. Experiences like this prompt us to think about what has happened – a process Kolb calls ‘reflective observation’. This can involve making active efforts to review what has happened from a variety of perspectives. In our example, this might involve exploring what has caused the communication difficulties from the perspective of each group. The point of this kind of reflection is to try to establish how to frame the experience properly in order to search for possible solutions. These come initially in the form of ‘abstract conceptualisations’ – that is, theories and concepts that enable the concrete experience to be placed in a broader conceptual framework.

A communication breakdown might then be understood in relation to broader ideas about organizational structure, inter-group behaviour or technological issues. Placing experience in these kinds of frameworks enables the development of possible solutions, which then need to be implemented back in the original setting through a process of ‘active experimentation’. The solutions clearly relate to the choice of theories. If the problem is structural, then different kinds of work processes might need to be designed. If the problem is group relations, then some form of mediation between groups might be possible. If the problem is technological, then experimenting with the tools through which groups communicate is the way forward. The final moment of the whole cycle is to intervene in the problem in such a way as to create a new concrete experience – although hopefully a more productive one – that sets the learning-cycle off again.

We might think of the ‘deductive’ and ‘inductive’ approaches to problem definition as representing two different ways of entering the Kolb cycle. A deductive, or theory-led approach, starts with abstract conceptualizations and works towards concrete experiences via experimentation. Conversely, an inductive approach starts with concrete experiences and moves, through reflection, towards theories and concepts. Placing these approaches in this context makes it clear that in both cases it is necessary to work with both theories and concrete, empirically grounded material. It will never be sufficient to confine oneself to either one or the other because both are fundamentally interlinked. We theorise in order to better understand real-world problems. We explore real-world problems with a view to developing theories and concepts. Together, both activities make up the process of academic research. In your problem definition, you can enter at either point in the Kolb cycle, so long as you do not forget that the purpose of what you are doing is to try to work your way around the whole cycle.

Review of the week

19 comments

This week you should have started to define the problem area you want to research, and begun to develop your thinking towards the research question. This will form a large part of explaining the context of your PhD proposal.

Consider again what is meant by ‘deductive’ and ‘inductive’. Discuss with fellow learners these terms and core approaches. Can you have a mix of both in a research project?

Another emphasis has been on audiences and stakeholders. You will write a thesis for yourself, your supervisor, your examiners, but also for much wider audiences. Reflect on the ways to ‘reach’ these different audiences. Will it all be by written thesis? What other routes – talks, presentations, posters, etc? You might already think about whether going to such efforts to talk to diverse audiences worries you – as well as research skills, you want to communicate themes and ideas verbally. What training might you need for that? Again, discuss with fellow learners.

And finally, while we have been talking generally in the steps above, you need already think about whether the University of Leicester would fit your research area. Can you find relevant staff and projects as well as departments? Thus, ask yourself: are you right for Leicester? Is Leicester right for you? Is yours a theme for one department or maybe shared between two? Discuss these issues with your fellows.

Next week we will look at developing a Literature Review.

Introduction to reviewing literature

9 comments

A good doctoral research proposal needs to include a well-developed literature review or assessment. The review serves several different purposes.

Firstly, it will demonstrate that you have engaged with or can show the ability to engage with the academic literature around a particular topic and have some knowledge of the theoretical and methodological approaches which are relevant to studying your research problem. Secondly, it should provide an overall context for what your research will be trying to do, which makes it possible to establish the feasibility of the research, and also establishes the criteria of success and failure that might be applied. Thirdly, it will offer a succinct statement of the tradition of work that you think is important and of the scholarly values to which you seek to aspire. Finally, as established last week in this course, it enables you to define a series of research questions that will guide and frame your work.

It is perhaps easier to define what a good literature review looks like by saying what it is not. Arguably, the most important thing here is that a literature review may well be fundamentally different to the kinds of essays you may have written in your previous studies (e.g. undergraduate, Masters, MSc). A common approach to essay writing is to offer an overview of a range of studies and approaches, evaluating each in turn, for example by following a historical chronology, before concluding that there are merits and drawbacks in every approach. This may be fine if what you want to do is convince the reader that you have read a textbook and can repeat the gist of the arguments presented there, but it may well fail to convince a potential PhD supervisor that you have clear depth to your research. By the same token, writing a series of bullet points or short paragraphs that summarise a set of studies or theories will also not be well received because this does not establish how these findings or concepts can be seen as relevant to your own proposed research.

What needs to be done instead is to write a ‘problem-oriented’ narrative that begins by identifying the overall issue and then gradually adds in scholarly works to develop an integrated framework, and ends in a set of clearly focused research questions. You could think of this as being like a short story or the script for a movie. All good stories start with a dramatic scene that places the reader immediately into the ‘action’. After this beginning, the characters are introduced and the narrative develops a series of relationships between them, during the course of which we learn more about their own qualities and personal histories. The narrative then builds towards a resolution, where the various threads of the story are woven together in a satisfying but, also, often challenging and clever, way. If you think of the literature review in this way as akin to a story rather than a summary essay, you will be on the right track.

This week, therefore, we will look at how to identify relevant research literature, and at how to structure the review. Towards the end of the week you will have the opportunity to write a first draft of your literature review for your peers to review and give feedback on, and so we recommend that you make a set of supporting notes as you go through the week to help you to prepare for that.

Getting started

6 comments

The obvious place to start is with what you already know. Look at any materials you have from previous studies, such as a Masters project or a professional scoping report, and attempt to identify related theories and authors who publish around the topic you are interested in.

You should then look at the work that such authors cite and refer to, and track this down. (If your materials do not have such citations then it is not a good model to follow!) Then repeat this again, gathering a third set of materials. This is a process known as ‘snowballing’: you start with one text, then look at the work it builds upon, and then gather up the next. In this way you can start to build up a picture of the research tradition in a specific area. En route you will also start to be critical in reading, selecting and judging the materials’ worth.

However, this does depend upon having a reasonably up-to-date text as your ‘starting point’ (i.e. if you start with a book from 1985, then you will not of course come across any of the (often extensive!) work done after that point). Ultimately, you will need to show that your knowledge of the literature is current. And with academic journals increasingly publishing articles online before they go – if at all – into a print issue (called e.g. ‘Online First’, ‘FirstView’ or similar) being up-to-date usually means including citations from the actual year in which you are writing.

For many people, the initial attempt to gain an overview of a topic/theme/field will probably mean that you start with a textbook. The advantages of this is that it will summarise a wide range of work and describe some of the major theories and ideas for each topic. The disadvantage of this is that the descriptions or information offered will typically be somewhat broad or superficial and not detailed enough for you to develop a good ‘story’. What you need to do, therefore, is to treat the textbook as simply the starting point for gathering further materials – a literature review that simply repeats a textbook description of a field of study will not be successful.

If you are moving into a new area of study or research, or are returning to study after a time outside of education, you may not have any materials from which to begin the snowballing process. In this case, it might well be tempting to start the process with an online search, which will very rapidly lead you to a site such as Wikipedia. While there is nothing wrong with doing this if you simply need to quickly learn what key terms mean (and sites such as Wikipedia can indeed provide useful essentials), it will not lead you to materials containing the many details you require.

A better idea is to use a more academically oriented search engine such as Google Scholar. This will generate a lot of results, although initially it may be difficult for some of you to work out which are useful to you. For example, a search for ‘Organisational Behaviour’ generates over one million results, with a mixture of very general textbooks and highly specific journal articles. Likewise a broad sub-field like ‘Landscape Archaeology’. Your best strategy here is first to try to establish some very general themes, based on the descriptions that are given of the work:

What seem to be the perspectives that researchers adopt?

Do these appear to change over time?

Which author names reappear and which names tend to come up when the history of the field is described?

What seem to be the core components or ideas that make up the area?

Which aspects of the field seem well covered and which not?

Make notes on all of these and use them to refine your search terms. By doing this several times over, you should be able to build up a basic picture of the research traditions in a particular area. What you now need to do is to look for material from specific authors or around particular theories and concepts. For example, in an historically-oriented project you will want first to focus in on a period or timespan; or, you will need to refine your study in terms of geographical setting. You want to narrow down to concepts like ‘Industrial warehousing’ or ‘Humour in Victorian Gothic novels’ or ‘Ancient household archaeologies’.

Also, try out a range of similar terms for aspects of what you are looking for as they may produce very different results – e.g. instead of just ‘museums’ it could be ‘museology and museogeography’ or instead of ‘buildings archaeology’ you could look to ‘cultural heritage domain’ or ‘built heritage participation’. The place to look for these is in the scholarly journals that are associated with a particular field. This is where you will find the detailed accounts of research that you will need for your literature review. A word of warning: if you’ve not done such searches before the mass of research ‘out there’ may seem very daunting and you may even find your own great research idea has been covered in some fashion already! But do persevere. And certainly you will recognise from these searches what fields ‘attract’ and how some themes are approached currently.

What our current students say - literature review

9 comments

In this short video, the University of Leicester PhD students we introduced to you last week talk about how they approached their literature review. Listen carefully to these – which do you feel fits your own thoughts about approaching this important task?

The literature during the proposal-- while writing the proposal, I did not tackle literature just for the proposal. It started way back during my master's days, reading for my dissertation topic. So when I needed to write a proposal for my PhD, I went through all the reading lists related to the topic as part of my master's reading list. I also looked at the bibliographies of many of those works, so that I got to find other related work easily. If I did not have time to read a particular book or did not know whether it helped me specifically, I would first target the summary or the book review written by some other author to understand whether that book is really relevant.

0:57Skip to 0 minutes and 57 secondsI also read abstracts of journal articles so that I could narrow it, because you know that a literature review is so wide it's like a sea. You cannot know everything and you cannot read everything. So it helps to target your work, your focus, your approach. And this is how I went doing my literature review. So I kind of targeted it and I tried to read as much as possible for my proposal. But it started a way long time ago. For me, I like to categorise different materials or different literatures. Some concerned with my research, then I will read in detail.

1:42Skip to 1 minute and 42 secondsBut some just have little or less related or concerned with my research, I will just skip-- skip the lines and find my ideas. Or if I see from the title of literature that it's not related to my research, I just put them away. I have to say that it's never a linear process, so it was difficult. I started first with key words, so I just put in "rubbish" and "waste" and "Nigeria." And then lots of things were coming up, but not the things that I really wanted, so to actually get into the literature, I started to think more about asking people.

2:31Skip to 2 minutes and 31 secondsAnd I think this is really the key, so having conversations with people who have been working in the area, so they mention some key authors. And then I do a literature search on those guys. And then I start to read about their thesis. So it comes with both reading and writing, so I couldn't really pinpoint where I started to get into the literature. But it got to a point where it became embodied really, but it's just from reading. I from memory sort of broke it down into the different areas of literature.

3:02Skip to 3 minutes and 2 secondsSo often for a PhD project, it's quite vast, so you sort of touch on a number of different areas or different literature fields for your question or your topic area. So I think I had a bit of a discussion around each of those different areas that were applicable to me, sort of reviewing what had been done before me. But I think most importantly, it's not just saying, "and this is what has been done." It's bringing out your own voice from that and identifying the gap, because the PhD is about contributing something.

3:42Skip to 3 minutes and 42 secondsSo I think your proposal, one of the most important things you need to do is to show how you're contributing to this field, so by reviewing what has already been done, but the most important part of that literature review is saying where you're going and what gap you're going to fill, whether that's like a method gap or a literature gap. It doesn't matter what the gap is, but just making sure you point out what it is. I did an MRes; I didn't do a taught master. So I basically-- I did it part-time, so I had two years of reading. And part of it, I already had to do a lit review for it already.

4:17Skip to 4 minutes and 17 secondsSo I'd done quite a lot of reading, as I said, on drugs history beforehand. But I think the best advice for tackling the lit review is, again it's tied to doing what you know, because if you're already doing some reading on inter-related stuff or your master's, I'd say that's a really good start. So start with a project that's generally related to what you're doing. For a good example, don't, for example, if you've been doing kind of like the history of Anglo-Saxon England and then you go, oh, I really want to do McCarthy's America, that obviously is a massive problem, because you have no context at all.

4:46Skip to 4 minutes and 46 secondsAs an international student especially, it's very tricky because the way I was taught in my bachelor's degree was not to think critically. So we always have to give back what we're given. But I think to bridge that gap, I started to think first, OK, so what's this author saying? I read a text and then I try to see what other people are saying with that text. So one way into that was with Google Scholar. So I would find one of the articles and then I'll see cited by this guy, so I try to get into the discussion, just following the timeline.

5:21Skip to 5 minutes and 21 secondsSo if the text I was reading was published in 2005, then I look down from 2005 to current, so I look at the debates. And so when I'm referring to an argument made in the 2005 publication, I would say that other authors have moved along other arguments to actually critique or to extend or to-- things like that.

7:44Skip to 7 minutes and 44 secondsMy data collection method is probably-- it's sort of at the centre of my whole PhD project. So I think for some PhDs, the data collection method is just a means to an end, whereas for mine, it's sort of part of the identity of the project. It's part of my contribution, really. So in my proposal, the data collection method came forward really strong, because that was part of what was new about what I was doing and how I was researching this area. So I used something called screen capture software, which my participants downloaded onto their laptops and they recorded their laptop screens when they were on Facebook, so I had like a live recording of their interactions online.

8:28Skip to 8 minutes and 28 secondsSo I do semi-structured interviews. I've done that for my master's dissertation and for my PhD. I've started looking at discourse analysis, because I look at material put out by governments and think tanks and policy institutes. These could be governmental documents. It could be treaties. It could be any sort of official documents, just to find out how countries are responding to certain actions from other countries. I also interview people in think tanks and policy institutes in the academia, journalists. So that's something I do. So I do discourse analysis. I do semi-structured interviews.

9:12Skip to 9 minutes and 12 secondsAnd I'm also working on a response framework to understand what a response is, a set of questions that helps one understand how countries are responding and if that action is actually a response to a previous action. Well, my study is a case study, so the case study's the main research method for me. And in case study, I also adopt multi-step like submethods to look into detailed stuff, the material, like I would adopt qualitative data and quantitative data, so I will use different methods. At the moment, I am employ a qualitative research approach, so specifically I use ethnographic observations, as well as in-depth interviews. I also use a bit of photographs as well.

10:18Skip to 10 minutes and 18 secondsNothing has changed with my methodology, but I think I actually got into the qualitative side of things because I am not really one of the strongest with mathematics or numeric-- my numeric ability is not very good, so yeah. I've used probably predominantly conversation analysis, which is sort of a very microanalysis of people's interactions and the language that they use. But actually, as I've sort of got on and I've engaged with my data further into my study, I've realised that I might have to actually draw upon other analysis methods as well, not just conversation analysis.

10:59Skip to 10 minutes and 59 secondsSo as you go on, you sort of realise that you need a set of different tools rather than just the one tool you thought you were going to need at the beginning.

Comments:

11 SEP

Literature reviews in a topic you’re interested in starts way before your PhD. As the students say you must be interested and if you have something which is irrelevant, set it aside. Coming from a background where literature review is given due attention is a bonus. In my research, l would go back and identify the literature review and probably gain more insight. I fully agree that there is a possibility that the bulk of the literature work could have been done at the post graduate stage. At the PhD stage, we are likely to get a new perspective by reading extra literature.

Like

Reply

Bookmark

Flag

Edoardo Gazzoni

Edoardo Gazzoni

Follow

10 SEP

I'm very lucky because in Italy we have a real strong attention on literature review. Anyway I'm going to approach a reserch problem that is near but not exactly in my past fields, so I'll need to strongly study some focused literature.

Like

Reply

Bookmark

Flag

Kala Rao

Kala Rao

Follow

10 SEP

As they say, the literature review is like a sea and Google Scholar has been quite helpful so far.

Like

Reply

Bookmark

Flag

Oliver Castaño Mallorca

Oliver Castaño Mallorca

Follow

10 SEP

To initiate research writing about knowledge something new in the field start asking for some cause. Then work some citations, also as a process of “snowballing” through a self-text-builder, always drafting and updating to research critiquing (avoiding plagiarism), so being oneself.

Like

Reply

Bookmark

Flag

MA

Mercy Atieno Odongo

Follow

09 SEP

I like the aspects of the literature review that identifies the gap whether in literature and policy and exploring your contribution in this regard. The second thing that stood out for me was the idea of looking at the abstract as literature is expansive then this provides a focused reading. This is insightful and very enlightening.

Finding the right literature without access to a university

12 comments

It can be challenging to gather academic literature without access to a university and its library. The main reason for this is that the private companies that have an effective oligopoly over academic publishing are very keen to protect the enormous revenues and profit margins that they make in publishing scholarly journals and books.*

If you do not have access to a university, the rate which publishers charge to view just an individual article is typically around £20. Getting hold of a sufficient number of articles to write a literature review through this route could cost several hundreds or even thousands of pounds… But things are gradually changing. ‘Open access publishing’ is now a growing trend in academic research, supported by government, research funding bodies and academics themselves. Most academic journals now give researchers the possibility to pay for their article to be made ‘open access’ – meaning that anyone can download a copy from the website of the journal. This is expensive, costing around £800 typically for ‘gold standard’ open access.

However many funding bodies now make it condition of funding research that the findings should be published open access, and so this may be built into the costs of doing research. When you are searching for articles, each journal should make it clear which articles are open access and which are not.

* To give one example, the Journal of International Management published by Elsevier costs £752 per year for each library which needs to stock it. It also charges individuals £86 per year if they wish to have a personal subscription. This money buys four issues in a given year, each around 100 pages, with an average of 6 articles. Each of these articles is provided, for free, by the authors, and has been rigorously peer reviewed by other academic, who have also worked for free, and edited by senior academics, who also – guess what! – supply their labour free of charge. The only cost to the publisher, beyond the pure print costs, usually takes the form of a small amount of money paid for a part-time editorial assistant. Moreover, publishers insist that authors sign over all copyright to their work on publication, which prohibits authors from publishing material elsewhere, and gives the publish rights to sell the material for their own profit as they see fit. Academic publishing is a very lucrative business indeed. If you want to know more about this, see the Related Links below for an article written by staff in the University of Leicester’s School of Management/Business.

3.5.