The stranger remained in his room until noon. All that time he did not get any meals. He rang his bell several times, but no one answered him.

The news of the burglary at the Vicarage arrived, and they put two and two together [15].

What the stranger did is unknown. Now and then one could hear curses, and a violent smashing of bottles.

The little group of scared but curious people gathered near the inn.

About noon the stranger suddenly opened his door and stood looking at the three or four people in the bar. “Mrs. Hall,” he called. Somebody went and called for Mrs. Hall.

Mrs. Hall appeared after an interval. She had come holding an unsettled bill. “Is it your bill you want, sir?” she said.

“Why haven’t you prepared my breakfast?”

“Why isn’t my bill paid?” said Mrs. Hall.

“I told you three days ago I expected money to arrive –”

“I told you three days ago I wasn’t going to wait for any money to arrive.”

The stranger swore.

“And keep your swearing to yourself, sir,” said Mrs. Hall.

The stranger looked angrier than ever. “Look here, my good woman –” he began.

“Don’t ’good woman’ me [16],” said Mrs. Hall.

“My money hasn’t come. Still I have some in my pocket –”

“Before I take any money from you, or you get any breakfasts,” said Mrs. Hall, “you have to tell me one or two things I don’t understand. I want to know what you did to my chair, and I want to know how it was your room was empty and how you got in it again? And I want to know –”

Suddenly the stranger raised his gloved hands, and said. “Stop!” with extraordinary violence. “You don’t understand,” he said, “who I am or what I am. I’ll show you.” Then he put his hand over his face and gave Mrs. Hall something which she took automatically. Then, when she saw what it was, she screamed loudly, and dropped it. The nose – it was the stranger’s nose! pink and shining – lay on the floor. Then he took off his spectacles, his hat, and pulled at his whiskers and bandages. Off they came.

It was worse than anything. Mrs. Hall, standing open‑mouthed and horrified, shrieked at what she saw, and ran to the door of the house.

Every one began to move. They were prepared for scars, disfigurement – but nothing! The bandages and false hair fell to the floor. Every one saw the figure up to the coat‑collar, and then – nothing, nothing at all!

People down the street heard shouts and shrieks, and looking up the street saw a crowd running out of the “Coach and Horses”.

They saw Mrs. Hall fall down, and Mr. Teddy Henfrey jump over her.

Everyone all the way down the street began running towards the inn, and in a short time a crowd of perhaps forty people gathered in front of the “Coach and Horses”. Everybody talked at once.

A few minutes later they saw Mr. Hall, very red and serious, then Mr. Bobby Jaffers, the village constable, marching towards the house. Mr. Hall marched up the steps, to the stranger’s door and found it open. Jaffers marched in, Hall next. They saw the headless figure, with bread in one gloved hand and cheese in the other.

“What the devil’s this?” came an angry question from above the collar of the figure.

“I have a warrant here, mister,” said Mr. Jaffers.

“Keep off!” said the stranger. Off came his glove, and was thrown in Jaffers’s face. In another moment Jaffers gripped him by the handless arm. He was kicked on the leg, but he kept his grip. The stranger was now headless and handless – for he had pulled off his gloves.

It was the strangest thing in the world to hear that voice coming as out of nothing. Jaffers took out a pair of handcuffs. Then he looked helpless.

“Damn it! Can’t use them!”

The stranger unbuttoned his coat. Then he started doing something with his shoes and socks.

“Why!” said Hall suddenly, “that’s not a man at all. It’s just empty clothes. Look! You can see inside his clothes. I could put my arm –”

He stretched his hand; it seemed to meet something in the air. “I wish you’d keep your fingers out of my eye,” said the angry voice.

“The fact is, I’m all here: head, hands, legs and all the rest of it, but I’m invisible.”

The suit, now all unbuttoned and hanging on the invisible body, stood up.

Several other men had now entered the room, so it was crowded. “Invisible, eh?” said Jaffers.

“It’s strange, perhaps, but it’s not a crime. Why am I attacked by a policeman?”

“Ah!” said Jaffers. “No doubt you are a bit difficult to see in this light, but I got a warrant and it’s all correct. What I’m after isn’t invisibility, it’s burglary. Somebody has broken into a house and taken money.”

The figure sat down and took off the shoes, socks, and trousers.

“Stop that,” said Jaffers, suddenly realizing what was happening. He gripped the coat, it struggled, and the shirt slipped out of it and left it empty in his hand. “Hold him!” said Jaffers loudly. “When he gets the clothes off –”

“Hold him!” cried every one, trying to catch the white shirt, which was now all that was visible of the stranger.

“Hold him! Shut the door! Don’t let him out. I got something! Here he is!” A lot of noise they made. In another moment the struggling, excited men were in the crowded hall.

“I got him!” shouted Jaffers, fighting against his unseen enemy. He got a violent blow in the face, and his fingers relaxed.

Across the road a woman screamed as something hit her, a dog was kicked and ran away.

The Invisible Man escaped. For a minute people stood amazed, and then came panic, and they ran through the village. But Jaffers lay quite still at the steps of the inn.

Chapter VII

Mr. Thomas Marvel

Mr. Thomas Marvel was sitting by the roadside about a mile and a half out of Iping. He was looking at a pair of boots. They were the best boots he had had for a long time, but too large for him. Mr. Thomas Marvel hated large boots, but they were really good. He put the boots on the grass, and looked at them. It suddenly occurred to him that they were very ugly.

“They’re boots, anyhow,” said a Voice behind him.

“They are the ugliest pair in the whole world!”

“H’m,” said the Voice.

“ A gentleman on tramp [17] sees a lot of boots. They give you good boots in this county. I’ve got my boots in this county ten years or more. And then they give you something like this.”

“It’s an ugly county,” said the Voice, “and pigs for people [18].”

Mr. Thomas Marvel turned his head over his shoulder first to the right, then to the left to look at the boots of the man he was talking to, but saw neither legs nor boots. He was greatly amazed. “Where are you?” said Mr. Thomas Marvel. He saw nothing but grass and bushes.

“Am I drunk?” said Mr. Marvel. “Have I had visions? Was I talking to myself?”

“Don’t be alarmed,” said the Voice.

“Where are you? Are you buried?” said Mr. Thomas Marvel after an interval.

There was no answer. The road was empty north and south, and the blue sky was empty too.

“It’s the drink,” said Mr. Thomas Marvel.

“It’s not the drink,” said the Voice.

“Oh!” said Mr. Marvel, and his face grew white. “It’s the drink,” he repeated. “ I could have sworn [19] I heard a voice,” he whispered.

“Of course you did.”

“It’s there again,” said Mr. Marvel, closing his eyes with his hands. He was suddenly taken by the collar and shaken violently.

“Don’t be a fool!” said the Voice.

“I’m mad! Or it’s spirits!” said Mr. Marvel.

“Neither mad nor spirits,” said the Voice.

“Listen! You think I’m just imagination?”

“What else can you be?” said Mr. Thomas Marvel.

“Very well,” said the Voice. “Then I’m going to throw stones at you.”

A stone flew through the air and hit Mr. Marvel’s shoulder. Mr. Marvel, turning, saw a stone hang in the air for a moment, and then fall at his feet. Another stone hit his foot. The tramp jumped, and screamed.

“Now,” said the Voice, “am I imagination?”

“I don’t understand it. Stones throwing themselves. Stones talking.”

“It’s very simple,” said the Voice. “I’m an invisible man. That’s what I want you to understand.”

“But where are you?” asked Mr. Marvel.

“Here! Six yards in front of you.”

“Oh, come! I’m not blind.”

“You’re looking through me.”

“What!”

“I am just a man who needs food and drink, clothes, too … But I’m invisible. You see? Invisible. Simple idea. Invisible.”

“What, real?”

“Yes, real.”

“Give me your hand,” said Marvel, “if you are real.”

He felt a hand touch his arm, then his face.

“Most remarkable!” Marvel’s face showed astonishment. “And there I can see a rabbit through you a mile away! Not a bit of you visible – except –”

He looked carefully in front of him. “Have you been eating bread and cheese?” he asked.

“You are quite right. It’s not assimilated into the system.”

“Ah!” said Mr. Marvel. “How did you do it?”

“It’s too long a story. I need help. I saw you suddenly. I was walking, mad with rage, naked, helpless, I could have murdered [20] … And I saw you – ‘Here,’ I said ‘is an outcast like myself. This is the man for me.’ So I turned back and came to you.”

“Lord!” said Mr. Marvel. “But how can I help you?”

“I want you to help me get clothes and shelter, and then with other things. If you won’t –… But you will – must. Help me – and I will do great things for you. An Invisible Man is a man of power.” He stopped for a moment to sneeze violently. “But if you betray me –,” he said.

He touched Mr. Marvel’s shoulder. Mr. Marvel gave a cry of terror at the touch. “I don’t want to betray you,” said Mr. Marvel. “All I want to do is to help you – just tell me what I have to do. I’ll do what you want.”

Chapter VIII

In the “Coach and Horses”

After the first panic was over, Iping became sceptical. It is much easier not to believe in an Invisible Man, and those who had actually seen him vanish in the air or felt the strength of his arm could be counted on the fingers of two hands. By the afternoon even those who believed in the Invisible Man were beginning to forget him.

About four o’clock a stranger entered the village. He was a short person in an extraordinarily shabby hat, and he appeared to be in a hurry [21]. He went to the “Coach and Horses.”

This stranger appeared to be talking to himself, as Mr. Huxter remarked. He stopped at the “Coach and Horses”, and, according to Mr. Huxter, it seemed he did not want to go in. At last he marched up the steps, and Mr. Huxter saw him turn to the left and open the door of the guest room. Mr. Huxter heard voices from the bar telling him of his mistake.

“That room’s private!” said Hall, and the stranger shut the door and went into the bar.

In a few minutes he reappeared. He stood looking about him for some moments, and then Mr. Huxter saw him walk towards the window of the room he had attempted to enter a few minutes before. The stranger took out a pipe, and began to smoke, looking around him carefully.

All this Mr. Huxter saw through the window of his shop, and the man’s suspicious behavior made him continue his observation.

At last the stranger put his pipe in his pocket, looked around, and vanished in the window.

Mr. Huxter ran out into the road to catch the thief. As he did so, Mr. Marvel reappeared, a big bundle in one hand, and three books in the other. As he saw Huxter he turned to the left, and began to run.

“Stop thief!” cried Huxter, and set off after him. He had hardly gone ten steps before he was caught in some mysterious way, and he was no longer running but flying through the air. He saw the ground suddenly close to his head, and all went black.

* * *

To understand what had happened in the inn, it is necessary to go back to the moment when Mr. Huxter first saw Mr. Marvel through the window.

At that moment Mr. Cuss and Mr. Bunting were in the guest room. They were seriously investigating what had happened in the morning, and were, with Mr. Hall’s permission, making a thorough examination of the Invisible Man’s things. Jaffers had recovered from his fall and had gone home. The stranger’s clothes had been taken away by Mrs. Hall, and the room tidied up. And on the table under the window, where the stranger had usually worked, Cuss had almost at once found three big books labeled

“Diary.”

“Diary!” said Cuss, putting the three books on the table. “Now we shall learn something. H’m – no name. Cipher. And figures.”

Cuss turned the pages over with a face suddenly disappointed. “It’s all cipher, Bunting.”

“There are no diagrams?” asked Mr. Bunting.

“No illustrations?”

“No,” said Mr. Cuss. “Some of it’s mathematical, and some of it’s Russian or some other language –”

The door opened suddenly.

Both men looked round, and saw a tramp.

“Bar?” asked he.

“No,” said both gentlemen at once. “Over the other side.”

“All right,” said the man in a low voice, different from the first question and closed the door.

“And now,” Mr. Bunting said, “these books.”

“One minute,” said Cuss, and went and locked the door. “Now I think we are safe from interruption.”

Someone sneezed as he did so.

“Very strange things have happened in Iping during the last few days – very strange. I cannot, of course, believe in the Invisible Man –” said Bunting.

“It’s incredible,” said Cuss, “incredible. But the fact remains that I saw – I certainly saw right down his sleeve –”

“But did you – are you sure… Hallucinations may be…”

Suddenly Mr. Bunting had a strange feeling at the back of his neck. He tried to move his head, and could not. The feeling was a grip of a heavy, firm hand. “Don’t move, little men,” whispered a voice, “or I’ll kill you both!” He looked into the face of Cuss, close to his own, and saw astonishment in it.

“Since when did you learn to pry into private papers?” said the Voice, and two chins struck the table.

“Since when did you learn to enter private rooms?” and the concussion was repeated. “Where have they put my clothes? Listen,” said the Voice. “I am a strong man, and I could kill you both and get away quite easily if I wanted to – do you understand? Very well. If I let you go, will you promise to do what I tell you?”

“Yes,” said Mr. Bunting, and the doctor repeated it. Then the pressure on the necks relaxed, and the doctor and vicar sat up, both very red in the face.

“When I came into this room, I expected to find my diary and clothes,” said the Invisible Man. “Where are they? My clothes are gone. I want clothes – and I must also have those three books.”

Chapter IX

The Invisible Man Returns

While these things were going on, and while Mr. Huxter was watching Mr. Marvel smoking his pipe outside, Mr. Hall and Teddy Henfrey were discussing the only topic that interested Iping. Suddenly they heard some noise in the guest room, a cry, and then – silence.

Mr. Hall understood things slowly but surely. “That isn’t right,” he said, and came towards the door of the guest room. Teddy followed him.

“Something is wrong,” said Hall, and Henfrey nodded agreement. There was a muffled sound of conversation in the room.

“You all right, sir?” asked Hall, knocking.

The muffled conversation stopped, for a moment silence, then a cry of “No! you don’t!”

There came sounds of struggle. Silence again.

“You – all – right – sir?” asked Mr. Hall again.

The vicar’s voice answered with a curious intonation. “Quite ri‑ight. Please don’t – interrupt.”

“Odd!” said Mr. Henfrey.

“Odd!” said Mr. Hall.

“Says, ‘Don’t interrupt,’” said Henfrey.

“I heard,” said Hall.

They remained listening, but couldn’t hear what the conversation was about. The sounds in the room were very odd.

Mrs. Hall appeared behind the bar. They all stood listening. Mrs. Hall was looking through the inn door, and saw the road and Huxter’s shop. Suddenly Huxter’s door opened, and Huxter appeared.

“Stop thief!” cried Huxter, ran down the road, and vanished.

At the same time they heard some noise from the guest room, and a sound of a window closing. All who were in the bar rushed out at once into the street. They saw Mr. Huxter jump in the air and fall on his face. Mr. Huxter was thrown on the ground. Hall saw Mr. Marvel vanishing round the corner of the church wall. He thought that this was the Invisible Man suddenly become visible, and ran after him. But Hall had hardly run a few yards before he gave a loud shout of astonishment [22] and went flying in the air. He hit on the running men, bringing them to the ground. A few people running after Mr. Marvel were also knocked with violent blows to the ground.

When Hall and Henfrey and the others ran out of the house, Mrs. Hall remained in the bar. And suddenly the guest room door was opened, and Mr. Cuss appeared and rushed at once out. “Hold him!” he cried, “don’t let him drop that bundle! You can see him as long as he holds the bundle.”

He knew nothing of Marvel. The Invisible Man had given him the books and bundle through the window. The face of Mr. Cuss was angry.

“Hold him!” he cried. “He’s got my trousers! – and all the vicar’s clothes!” He ran past Huxter lying on the ground, and was knocked off his feet. Mr. Cuss rose, and was hit again. Behind him he heard a sudden yell of rage. He recognized the voice of the Invisible Man. In another moment Mr. Cuss was back in the inn.

“He’s coming back, Bunting!” he said, rushing in. “Save yourself!”

Mr. Bunting stood trying to clothe himself in newspapers.

“Who’s coming?” he said.

“Invisible Man!” said Cuss, and rushed to the window. “We’d better get out from here. He’s fighting mad! Mad!”

In another moment he was out.

“Lord!” said Mr. Bunting, hesitating between two horrible alternatives. He heard a struggle in the passage of the inn, and made a decision.

He jumped out of the window, pressing newspapers to his body, and ran away as fast as his fat little legs could carry him.

All villagers ran for their houses and locked themselves up. The Invisible Man, mad with rage, broke all the windows in the “Coach and Horses”. And after that, he was neither heard, seen, nor felt in Iping any more. He vanished absolutely.

Chapter X

Mr. Marvel Escapes

When it was getting dark, a man in a shabby hat was marching on the road to Bramblehurst. He carried three books, and a bundle. He was accompanied by a Voice and seemed to be beaten by unseen hands.

“If you give me the slip [23] again,” said the Voice;

“if you attempt to give me the slip again –”

“Lord!” said Mr. Marvel. “Don’t touch my shoulder. It hurts.”

“I will kill you,” said the Voice.

“I didn’t try to give you the slip,” said Marvel, with tears in his voice. “I swear I didn’t. I didn’t know the way, that was all!”

“It’s bad that my secret is known, without your escaping with my books. No one knew I was invisible! And now what am I to do?”

“What am I to do?” asked Marvel.

“It will be in the papers! Everybody will be looking for me.”

The Voice swore. Mr. Marvel grew even more desperate, and he stopped.

“Go on. You’re a poor tool, but I shall have to use you,” said the Voice sharply.

“I’m a miserable tool,” said Marvel.

“You are,” said the Voice.

“I’m the worst possible tool you could have,” said Marvel. “I’m not strong.”

“No?”

“And my heart’s weak. I wish I was dead,” said Marvel. “I tell you, sir, I’m not the man for it.”

“Shut up,” said the Invisible Man. “I want to think.”

They were coming to a village.

“I shall keep my hand on your shoulder,” said the Voice, “all through this village. Go straight and try no foolery [24]. It will be the worse for you [25] if you do.”

“I know that,” said Mr. Marvel, “I know all that.”

The unhappy‑looking figure walked through the little village, and vanished into the darkness in the direction of a small town Port Stowe.

* * *

The “Jolly Cricketers [26] ” is in Burdock just at the bottom of the hill, on the road from Port Stowe. The barman talked of horses with a cabman, while a black‑bearded man was eating biscuit and cheese, drank beer, and talked with a policeman.

“What’s the matter?” said the cabman. Somebody ran by outside.

Footsteps approached, the door opened violently, and Marvel, his hat gone, the collar of his coat torn, rushed in, and attempted to shut the door.

“Coming!” he shrieked with terror. “He’s coming. The Invisible Man! After me. For God’s sake [27]! Help! Help!”

“Shut the doors,” said the policeman. “Who’s coming? What’s the matter?” He went to the door and bolted it.

“Lock me in – somewhere,” said Marvel. “He’s after me. I gave him the slip. He said he’d kill me, and he will.”

“You’re safe,” said the man with the black beard. “The door’s shut. What’s it all about?”

A blow suddenly made the bolted door shiver, and was followed by other blows and shouting outside.

“Who’s there?” cried the policeman.

“He’ll kill me – he’s got a knife or something. For God’s sake –!” Mr. Marvel shrieked.

“Come in here,” said the barman. Mr. Marvel rushed behind the bar. “Don’t open the door,” he screamed. “Please don’t open the door.”

“Is this the Invisible Man, then? Newspapers are full of him,” said the man with the black beard.

The window of the inn was suddenly smashed, and there was screaming and running to and fro in the street.

“If we open, he will come in. There’s no stopping him [28],” said the policeman.

“If he comes–,” said the man with the black beard, holding a revolver in his hand.

“ That won’t do [29],” said the policeman, “that’s murder.”

“I’m going to shoot at his legs,” said the man with the beard.

“Are all the doors of the house shut?” asked Marvel.

“Lord!” said the barman. “There’s the back door!”

He rushed out of the bar. In a minute he returned.

“The back door was open,” he said.

“He may be in the house now,” said the cabman.

Just as he said so they heard Marvel shriek.

They saw Marvel struggling against something unseen. Then he was dragged to the back door, head down.

The policeman rushed to him, followed by the cabman, gripped the invisible hand that held Marvel, was hit in the face and fell. Then the cabman gripped something. “I got him,” said the cabman. Mr. Marvel was released, suddenly dropped to the ground, and crawled behind the legs of the fighting men to the door. The voice of the Invisible Man was heard for the first time, he cried as the policeman stepped on his foot.

The struggle went on, and no one saw Mr. Marvel slip out of the door and run away. He left the back door open behind him, and in a moment thecrowd of fighting men was outside.

“Where’s he?” cried the policeman, stopping.

A stone flew by his head.

“I’ll show him,” shouted the man with the black beard, and shot five times.

A silence followed. “ Come and feel about for his body [30],” said the man with the black beard.

Chapter XI

The Invisible Man is Coming

In the early evening Dr. Kemp was sitting in his study in the house on the hill overlooking Burdock. It was a pleasant room, with three windows and bookshelves with books and scientific publications, and a writing‑table, and under the window a microscope, some cultures, and bottles of reagents.

Dr. Kemp was a tall young man, with hair almost white, and the work he was doing would earn him, he hoped, the fellowship of the Royal Society [31].

For a minute, perhaps, he sat looking out at the hill, and then his attention was attracted by the figure of a man, running over the hill towards him.

“Another of those fools,” said Dr. Kemp.

“Like that fool who ran into me this morning round a corner, with his ‘Invisible Man’s coming, sir!’ One might think [32] we were in the thirteenth century.”

He got up, went to the window, and stared at the hillside and the figure running down it.

“Fools!” said Dr. Kemp, walking back to his writing‑table.

Dr. Kemp continued writing in his study until he heard shots. Crack, crack, crack, they came one after the other.

“Who’s shooting in Burdock?” said Dr. Kemp listening.

He went to the window, and looked down. He saw a crowd by “The Cricketers”, and watched.

After five minutes, Dr. Kemp returned to his writing desk.

About an hour after this the front door bell rang. He heard the servant answer the door, and waited for her, but she did not come.

“What was that?” said Dr. Kemp.

He went downstairs from his study, and saw the servant. “Was that a letter?” he asked.

“There was nobody at the door, sir,” she answered.

Soon he was hard at work again, and he worked till two o’clock. He wanted a drink, so he took a candle and went down to the dining‑room for whisky.

Dr. Kemp’s scientific investigations had made him a very observant man, and as he crossed the hall he noticed a dark spot on the floor. He put down the whisky, bent, and touched the spot. It felt like drying blood.

He returned upstairs looking about him and thinking of the blood spot. Upstairs he saw something, and stopped astonished. There was blood on the door‑handle of his room.

He looked at his own hand. It was quite clean, and then he remembered that the door of his room had been open when he came from his study, and he had not touched the handle at all. He went straight into his room. There was blood on his bed, and the sheet had been torn. On the farther side the bedclothes were depressed as if someone had been sitting there.

Then he heard a low voice say, “Lord! – Kemp!” But Dr. Kemp did not believe in voices.

He stood staring at the blood on his sheets. Was that really a voice? He looked about again, but noticed nobody. Then he heard a movement across the room. He put down his whisky on the dressing‑table. Suddenly, he saw a blood‑stained bandage hanging in the air, near him. He stared at this in amazement. It was an empty bandage – a tied bandage, but quite empty.

“Kemp!” said the Voice, quite close to him. “I am an Invisible Man.”

Kemp was not very much frightened or very greatly surprised at the moment. He did not realise it was true. “I thought it was all a lie,” he said. “Have you a bandage on?”

“Yes,” said the Invisible Man.

“Oh!” said Kemp. “But this is nonsense. It’s some trick.” He wanted to touch the bandage, and his hand met invisible fingers. The hand gripped his arm. He struck at it.

“ Keep steady [33], Kemp, for God’s sake! I want help badly. Stop! Kemp, keep steady!” cried the Voice.

Kemp opened his mouth to shout, and the corner of the sheet was put between his teeth. The Invisible Man pushed him down on the bed.

“Lie still, you fool!” said the Invisible Man in Kemp’s ear.

Chapter XII

Dr. Kemp’s Visitor

Kemp struggled for another moment, and then lay still.

“If you shout, I’ll smash your face,” said the Invisible Man. “I’m an Invisible Man. It is no trick and no magic. I am really an Invisible Man. And I want your help. Don’t you remember me, Kemp? Griffin, of University College. I have made myself invisible. I am just an ordinary man, a man you have known.”

“Griffin?” said Kemp.

“Griffin,” answered the Voice. “A younger student than you were, an albino, six feet high, with a pink and white face and red eyes, who won the medal for chemistry.”

Kemp thought. “It’s horrible,” he said.

“Yes, it’s horrible. But I’m wounded and in pain, and tired… Kemp, give me some food and drink.”

Kemp stared at the bandage as it moved across the room, then saw a chair dragged along the floor to the bed. The seat was depressed.

“Give me some whisky. I’m near dead.”

“It didn’t feel so. Where are you? Whisky … Where shall I give it you?”

Kemp felt the glass taken away from him. It hung in the air twenty inches above the chair.

He stared at it in amazement.

“This is – this must be – hypnotism. I demonstrated this morning,” began Kemp, “that invisibility is –”

“ Never mind [34] what you’ve demonstrated! I’m hungry,” said the Voice, “and the night is cold to a man without clothes.”

“Hungry?” said Kemp.

“Yes,” said the Invisible Man, drinking whisky. “Have you got a dressing‑gown?”

Kemp walked to a wardrobe, and took out a dressing‑gown. It was taken from him. It hung for a moment in the air, stood, and sat down in his chair.

“This is the insanest thing I’ve ever seen in my life!”

Kemp went downstairs to look for food. He came back with some cold cutlets and bread, and put them on a small table before his guest. A cutlet hung in the air with a sound of chewing.

“It was my good luck that I came to your house when I was looking for bandages. And it’s my bad luck that blood shows, isn’t it? Gets visible as it coagulates. I’ve changed only the living tissue, and only for as long as I’m alive … I’ve been in the house three hours.”

“But how’s it done?” began Kemp, in a tone of exasperation. “The whole business – it’s insane from beginning to end.”

“Quite sane,” said the Invisible Man; “perfectly sane.”

“How did the shooting begin?” he asked.

“There was a fool – a help of mine, curse him! – who has stolen my money. Moreover, he has stolen my diaries. We stopped at an inn in Port Stowe, a few miles from here. And he gave me the slip with my money and my diaries in the morning, before I got up.”

“Is he invisible, too?”

“No.”

“You didn’t do any shooting?” Kemp asked.

“Not me,” said his visitor. “Some fool I’d never seen.”

After he had done eating, the Invisible Man demanded a cigar. It was strange to see him smoking: his mouth and throat, and nose became visible as smoke filled them.

“ I’m lucky to have met you [35], Kemp. You haven’t changed much. I must tell you. We will work together!”

“But how was it all done?” said Kemp.

“For God’s sake let me smoke, and then I will begin to tell you.”

But the story was not told that night. The Invisible Man’s hand was growing painful; he was too tired. He spoke of Marvel, his voice grew angry.

“He was afraid of me – I could see he was afraid of me,” said the Invisible Man many times. “He wanted to give me the slip from the very start! I was furious. I should have killed him [36] – I haven’t slept for three days, except a couple of hours or so. I must sleep now.”

“Well, sleep in my room.”

“But how can I sleep? How I want to sleep!”

“Why not?”

“Because I don’t want to be caught while I sleep,” he said slowly.

Kemp stared at him.

“What a fool I am!” said the Invisible Man.

“I’ve put the idea into your head.”

Chapter XIII

The Invisible Man Sleeps

“I’m sorry,” said the Invisible Man, “if I cannot tell you all what I have done to‑night. I am tired. I have made a discovery. I wanted to keep it to myself. I can’t. I must have a partner. And you… We can do such things… But tomorrow.”

Kemp stood staring at the headless dressinggown.

“It’s incredible,” he said. “But it’s real!

Good‑night,” said Kemp.

Suddenly the dressing‑gown walked quickly towards him.

“No attempts to catch me! Or –” said the dressing‑gown.

Kemp’s face changed a little. “I thought you called me a partner,” he said.

Kemp closed the door behind him, and the key was turned upon him. “Am I dreaming? Has the world gone mad, or have I?” Kemp said. “Locked out of my own bedroom!” He shook his head hopelessly, and went downstairs to his consulting‑room, and began walking to and fro.

“Invisible!” he said. “Is there such a thing as an invisible animal?… In the sea – yes. Thousands – millions! In the sea there are more things invisible than visible! I never thought of that before… And in the ponds too! All those little things in ponds – bits of colourless jelly!… But in air! No! It can’t be. But after all – why not?”

He took the morning paper, and read the account of a “Strange Story from Iping”.

“He wore a diguise!” said Kemp. “He was hiding! No one knew what had happened to him.”

He took the St. James’s Gazette, opened it, and read: “A Village in Sussex [37] Goes Mad”.

“Lord!” said Kemp, reading an account of the events in Iping. “Ran through the streets striking right and left. Mr. Jaffers and Mr. Huxter in great pain – still unable to describe what they saw. Vicar in terror. Windows smashed.”

He dropped the paper and stared in front of him, then re‑read the article.

“He’s not only invisible,” he said, “but he’s mad!”

He was too excited to sleep that night. In the morning he gave the servant instructions to lay breakfast for two in the study. The morning’s paper came with an account of remarkable events in Burdock. Kemp now knew what had happened at the “Jolly Cricketers”. It seems like rage growing to mania! What can he do! And he’s upstairs free as the air. “What ought I to do?” he said.

He wrote a note, and addressed it to “Colonel Adye, Burdock.”

The Invisible Man woke up as Kemp was doing this. He awoke in a bad temper, and Kemp heard a chair knocked over and a glass smashed.

Kemp hurried upstairs.

“What’s the matter?” asked Kemp, when the Invisible Man opened the door.

“Nothing,” was the answer.

“But the smash?”

“Fit of temper,” said the Invisible Man.

“You often have them.”

“I do.”

“All the facts are out about you,” said Kemp.

“All that happened in Iping and down the hill. The world knows of the invisible man. But no one knows you are here.”

The Invisible Man swore.

“The secret’s out. I don’t know what your plans are, but, of course, I’ll help you. There’s breakfast in the study,” said Kemp, speaking as easily as possible.

Chapter XIV

Certain First Principles

“Before we can do anything else,” said Kemp at breakfast, “I must understand a little more about this invisibility of yours.” He had sat down, after one nervous look out of the window.

“It’s simple,” said Griffin.

“No doubt to you, but –” Kemp laughed.

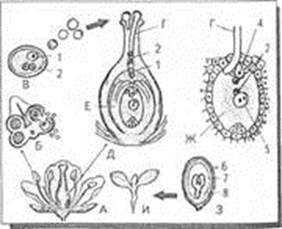

“Well, to me it seemed wonderful at first. You know I dropped medicine and took up physics? Well, I did. Light interested me. I had hardly worked for six months before I found a general principle of pigments and refraction – a formula. It was an idea how to lower the refractive index of a substance, solid or liquid, to that of air, and so to make it invisible.”

“That’s odd!” said Kemp. “But still I don’t quite see …”

“You know quite well that either a body absorbs light or it reflects or refracts it,” said Griffin. “If it neither reflects or refracts nor absorbs light, it cannot be visible. You see a red box, for example, because the colour absorbs some of the light and reflects the rest, all the red part of the light to you. If it did not absorb any part of the light, but reflected it all, then it would be a shining white box. A diamond box would neither absorb much of the light nor reflect much from the surface, but just here and there the light would be reflected and refracted, so that you would see some brilliant reflections. A glass box would not be so brilliant, not so clearly visible as a diamond box, because there would be less refraction and reflection. See that? From certain points you would see quite clearly through it. Some kinds of glass would be more visible than others. A box of very thin glass would be hard to see in a bad light, because it would absorb hardly any light and refract and reflect very little. And if you put a sheet of glass in water, it would almost vanish, because light passing from water to glass is only a little refracted or reflected. It is almost as invisible as any gas in air.”

“Yes,” said Kemp, “Any schoolboy nowadays knows all that.”

“And here is another fact any schoolboy will know. If a sheet of glass is smashed and beaten into a powder, it becomes much more visible while it is in the air. This is because light is refracted and reflected from many surfaces of the powdered glass. In the sheet of glass there are only two surfaces, in the powder the light is reflected or refracted by each piece it passes through. But if the powdered glass is put into water it vanishes. The powdered glass and water have much the same refraction index, that is, the light is very little refracted or reflected in passing from one to the other.

“The powdered glass might vanish in air, if its refraction index could be the same as that of air. Then there would be no refraction or reflection as the light passed from glass to air.”

“Yes, yes,” said Kemp. “But a man’s not powdered glass!”

“No,” said Griffin. “He’s more transparent!”

“Nonsense!”

“Have you already forgotten your physics in ten years? Just think of all the things that are transparent and seem not to be so! Paper, for example, is made of transparent fibres, and it is white and visible for the same reason that a powder of glass is white and visible. If you oil white paper, so that there is no longer refraction or reflection except at the surfaces, it becomes as transparent as glass. And not only paper, but bone, Kemp, flesh, hair, and nerves; in fact, the whole man, except the red of his blood and the dark pigment of hair, are all made of transparent, colourless tissue. Most fibres of a living tissue are no more visible than water.”

“Of course!” cried Kemp. “I was thinking only last night of the sea jelly‑fish!”

“Yes! And I knew all that a year after I left London – six years ago. But I kept it to myself. Oliver, my professor, was a thief of ideas! And you know the system of the scientific world. I went on working, I did not publish anything, I got nearer and nearer making my formula into an experiment – a reality. I told no one, because I wanted to become famous. I took up the question of pigments, and suddenly – by accident – I made a discovery in physiology.”

“Yes?”

“You know the red substance of blood – it can be made white – colourless!”

Kemp gave a cry of amazement.

“I remember that night. It was late at night. It came suddenly into my mind. I was alone, the laboratory was still … ‘An animal – a tissue – could be made transparent! It could be made invisible! All except the pigments. I could be invisible,’ I suddenly realized what it meant to be an albino with such knowledge. ‘I could be invisible,’ I said.

“I thought of what invisibility might mean to a man. The power, the freedom. I didn’t see any drawbacks.

“And I worked three years, with the professor always watching me. And after three years of secrecy and trouble, I found that to finish it was impossible.”

“Why?” asked Kemp.

“Money,” said the Invisible Man. “I robbed the old man – robbed my father. The money was not his, and he shot himself.”

For a moment Kemp sat in silence, then struck by a thought, he rose, took the Invisible Man’s arm, and turned him away from the window.

“You are tired,” he said, “and while I sit you walk about. Have my chair.”

He stood between Griffin and the window.

“It was last December,” Griffin said. “I took a room in London, in a big house near Great Portland Street. I had bought apparatus with my father’s money, and the work was going on successfully.

“Suddenly I learned of my father’s death. I went to bury him. My mind was still on this research, and I did not lift a finger to save his reputation. I remember the funeral, the cheap ceremony, and the old college friend of his. I did not feel a bit sorry for my father. He seemed to me foolishly sentimental. His funeral was really not my business. It was all like a dream. As I came home, in my room there were the things I knew and loved, my apparatus, my experiments.”

Chapter XV

The Experiment

“I will tell you, Kemp, later about all the processes. We need not go into that now. They are written in cipher in those books that tramp has hidden. We must find him. We must get those books again. I was to put a thing whose refractive index was to be lowered, between two centres of vibration. My first experiment was with a bit of white wool. It was the strangest thing in the world to see it become transparent and vanish.

“And then I heard a miaow, and saw a white cat outside the window. A thought came into my head. ’Everything is ready for you,’ I said, and went to the window, and called her. She came in. The poor animal was hungry – and I gave her some milk.”

“And you processed her?”

“Yes. I gave her some drugs. And the process failed.”

“Failed?”

“The pigment at the back of the eye didn’t go. I put her on the apparatus. And after all the rest had vanished, two little ghosts of her eyes remained. She miaowed loudly, and someone came knocking. It was an old woman from downstairs, who suspected me of vivisecting. I applied some chloroform, and answered the door. ‘Did I hear a cat?’ she asked. ‘Not here,’ said I, very politely. She looked past me into the room. She was satisfied at last, and went away.”

“How long did it take?” asked Kemp.

“Three or four hours – the cat. The bones and nerves and the fat were the last to go, and the back of the eye didn’t go at all.

“About two the cat woke up and began miaowing. I remember the shock I had – there were just her eyes shining green – and nothing round them. She just sat and miaowed at the door. I opened the window and let her out. I never saw nor heard any more of her.

“I thought of the fantastic advantages an invisible man would have in the world.

“But I was tired and soon went to sleep. When I woke up, someone was knocking at the door. It was my landlord. The old woman had said I vivisected her cat. The laws of this country, he said, were against vivisection. And the vibration of my apparatus could be felt all over the house, he said. That was true. He walked round me in the room, looking around him. I tried to keep between him and the apparatus, and that made him more curious. What was I doing? Was it legal? Was it dangerous? Suddenly I had a fit of temper. I told him to get out. He began to protest. I had him by the collar, threw him out, and locked the door.

“This brought matters to a crisis. I did not know what he would do, I could not move to any other rooms, I had only twenty pounds left. Vanish!

“I hurried out with my three books of notes, my cheque book – the tramp has them now – and sent them from the nearest Post Office to myself to another Post Office in Great Portland Street.

“It was all done that evening and night. While I was still sitting under the affect of the drugs that decolourise blood, there came a knocking at the door. I rose, and opened the door. It was the landlord. He saw something odd about my hands, and looked in my face.

“For a moment he stared. Then he gave a cry, and ran to the stairs. I went to the looking‑glass. Then I understood his terror… My face was white – like white stone.

“But it was horrible. I was in pain. I understood now why the cat had miaowed until I chloroformed it. At last the pain was over. I shall never forget the strange horror of seeing my body becoming transparent, the bones and arteries vanishing.

“I was weak and very hungry. I went and stared in my looking‑glass – at nothing, but some pigment of my eyes. I dragged myself back to the apparatus, and finished the process.

“I slept till midday, when I heard knocking. I felt strong again. I listened and heard a whispering. I got up, and as noiselessly as possible began to destroy the apparatus. There was knocking again and voices called, first my landlord’s and then two others. Someone tried to break the lock. But the bolts stopped him.

“I stepped out of the window on to the window‑sill, and sat down, invisible, but trembling with anger, to watch what would happen. They broke the door and rushed in. It was the landlord and his two sons. Behind them was the old woman from downstairs.

“You may imagine their astonishment at finding the room empty. One of the young men rushed to the window at once, and looked out.

His face was a foot from my face. He stared right through me. The old man went and looked under the bed. I sat outside the window and watched them.

“It occurred to me that if a well‑educated person saw my unusual radiators, they would tell him too much. I got into the room, and smashed both apparatus. How scared they were!…

Then I slipped out of the room and went downstairs.

“I waited until they came down. As soon as they had gone to their rooms, I slipped up with a box of matches, and fired my furniture –”

“You fired the house?” said Kemp.

“Yes, I fired the house! I was only just beginning to realise the extraordinary advantage my invisibility gave me.”

Chapter XVI

New Life Begins

“As I got on Great Portland Street, I was hit violently behind, and turning, saw a boy carrying a box of bottles. His astonishment was so funny that I laughed aloud. I took the box out of his hands, and threw it up into the air.

“A few people crowded around us. I realized what I had done. In a moment the crowd would be all around me, and I should be discovered. I pushed by a boy, ran across the road, and soon reached Oxford Street.

“In a moment someone stepped on my foot. I felt very cold. It was a bright day in January, and I was naked, and the mud on the road was freezing. I had not thought that, transparent or not, I should be cold.

“Then an idea came into my head. I jumped into an empty cab. And so, cold and scared, I drove along Oxford Street. I was not feeling as happy and powerful as I had when leaving my house a few minutes before. This invisibility, indeed! My one thought was how to get out of trouble.

“A woman stopped my cab, and I jumped out just in time to escape her. I was now very cold, and felt so unhappy that I cried as I ran.

“A little white dog ran up to me, nose down. I had never realised it before, how dangerous a dog could be for me. He began barking, showing that he felt me. I ran on and on until I saw a big crowd.

“I ran up the steps of a house, and stood there until the crowd had passed. Happily the dog stopped, too, then ran away.

“Two boys stopped at the steps near me. ’Do you see bare footmarks?’ said one.

“I looked down and saw the boys staring at the muddy footmarks I had left on the steps.

‘A barefoot man has gone up the steps,’ said one. ‘And he hasn’t come down.’

“‘Look there, Ted,’ said one of the young detectives, and pointed at my feet. I looked down and saw a silhouette of my muddy feet.

“‘Why, it’s just like the ghost of a foot, isn’t it?’ He stretched out his hand. A man stopped to see what he was catching, and then a girl. In another moment he would have touched me [38]. Then I made a step, and jumped over onto the steps of the next house. But the smaller boy saw the movement.

“‘What’s the matter?’ asked someone.

“‘Feet! Look!’

“In another moment I was running, with six or seven astonished people following my footmarks. I ran round corners and across roads, and then as my feet grew hot I cleaned them with my hands. I did not leave footmarks any more.

“This running warmed me, but I had cut my foot, and there was blood on it. It began snowing. And every dog was a terror to me.”

* * *

“So last January I began this new life. I had no home, no clothes, no one in the whole world whom I could ask for help. I had to get out of the snow, to get myself clothes, then I could make plans. I could see before me – the cold, the snowstorm and night.

“And then I had a good idea. I went to a big department store, where you can find everything: meat, furniture, clothes.

“I did not feel safe there, however, people were going to and fro, and I walked about until I came upon a big furniture section. I found a resting‑place, and I decided to remain in hiding until closing time. Then I should be able, I thought, to find food and clothes and disguise, perhaps sleep on a bed. My plan was to get clothes, money, and then my books at the Post Office, to stay somewhere, and realise the advantages of my invisibility (as I still imagined).

“Closing time arrived quickly. My first visit was to the clothes section, where I found what I wanted – trousers, socks, a jacket, a coat, and a hat. I began to feel man again, and my next thought was food.

“Upstairs was a restaurant, and there I got cold meat and coffee. I also saw a lot of chocolate, and some wine. Then I went to sleep on a bed, very warm and comfortable.

“As I woke up, I sat up, and for a time I could not understand where I was. Then I saw two men approaching. I got up, looking about me for some way of escape, and the sound of my movement made them look at me. ‘Who’s that?’ cried one, and ’Stop there!’ shouted the other. I ran round a corner and into a boy of fifteen. He shouted and I knocked him down, rushed past him, turned another corner. In another moment feet ran past and I heard voices shouting, ‘All to the doors!’ and giving one another advice how to catch me. But it did not occur to me at the moment to take off my clothes, as I wanted to get away in them. ‘Here he is!’

“I gripped a chair, and threw it at the man who had shouted, and rushed up the stairs. He came upstairs after me. Upstairs were a lot of those bright pots. I took one of them, and smashed it on his silly head. I rushed madly to the restaurant, and there was a man in white like a cook. I found myself among lamps. I hid among them and waited for my cook, and as he appeared, I smashed his head with a lamp. Down he went, and I began taking off my clothes as fast as I could.

“This way, Policeman,’ I heard someone shouting. I ran and found myself in my furniture section again, and hid there. The policeman and three other men came there. They saw my clothes. ‘He must be somewhere here,’ said one of the men.

“But they did not find me. I stood watching them and cursing my bad luck in losing the clothes. About eleven o’clock, when the snow had stopped and it was a little warmer, I went out without any plans in my mind.”

Chapter XVII

In Drury Lane

“I had no home – no clothes, – to get dressed was to lose all my advantage,” said the Invisible Man, “I could not eat, because unassimilated food made me grotesquely visible again.”

“I never thought of that,” said Kemp.

“Neither had I. And the snow was another danger. I could not go out in snow – it would fall on me and show me. Rain, too, would make me visible. Moreover, I gathered dirt on my body. It could not be very long before I became visible because of it. My most urgent problem was to get clothes. I remembered that some theatrical costumiers had shops in that district.

“At last I reached a little shop in Drury Lane [39]. I looked through the window, and, as there was no one inside, entered. I walked into a corner behind a looking‑glass. For a minute or so no one came, then a man appeared.

“My plan was to get there a wig, mask, glasses, and costume. And, of course, I could rob the house of money.

“The man looked about, but he saw the shop empty. ‘Damn the boys!’ he said. He went to look up and down the street. He came in again in a minute, and went back to the house door.

“I followed him, and at the noise of my movement he stopped. I did so too, surprised by his quickness of ear. He slammed the house door in my face.

“Suddenly I heard his quick steps returning, and the door opened. He stood looking about the shop like a man who was not satisfied. Then he examined all the shop. He had left the house door open, and I slipped into a small room.

“Three doors opened into the room, one going upstairs and one down, but they were all shut. I could not get out of the room while he was there, and I could not move because of his quickness of ear. Luckily, he soon came in and went downstairs to a very dirty kitchen. I followed him. He began to wash up, and I returned upstairs and sat in his chair by the fire.

“I waited there for very long, and at last he came up and opened the upstairs door. I went after him.

“On the staircase he stopped suddenly, so that I nearly ran into him. He stood looking back right into my face, and his eye went up and down the staircase. Then he went on up again.

“His hand was on the handle of a door and then he heard the sound of my movements about him. The man had very good hearing. ‘If there’s any one in this house –’ he cried, and rushed past me downstairs. But I did not follow him; I sat on the staircase until his return.

“Soon he came up again, opened the door of the room, and, before I could enter, slammed it in my face.

“I decided to examine the house as noiselessly as possible. The house was very old with a lot of rats. In one room I found a lot of old clothes. While I was sorting them out, I heard his steps, and saw him near me holding a revolver in his hand. I stood still while he stared about suspiciously.

“He shut the door, and I heard the key turn in the lock. I was locked in. I decided to examine the clothes before I did anything else, and this brought him back. This time he touched me, jumped back with amazement, and stood astonished in the middle of the room, revolver in hand.

“‘Rats,’ he said. By this time I knew he was alone in the house, and so I knocked him on the head.”

“Knocked him on the head?” exclaimed Kemp.

“Yes, as he was going downstairs. Hit him from behind with a chair. He went downstairs like a bag.”

“But –”

“Kemp, I had to get out of that house in a disguise, without his seeing me [40]. I couldn’t think of any other way of doing it.”

“But still,” said Kemp, “the man was in his own house, and you were robbing.”

“Robbing! Damn it! Can’t you see my position? I was in trouble! And he made me mad too – hunting me about the house, with his revolver, locking and unlocking doors. What was I to do?”

“What did you do next?” said Kemp.

“I was hungry. Downstairs I found some bread and cheese, and ate them. Then I went to the room with the old clothes.

“I chose a false nose, dark glasses, whiskers, a wig, a coat and trousers. In a desk in the shop were three sovereigns and about thirty shillings. After I put everything on, I looked at myself in the looking‑glass in the shop. I looked odd, but I could go out. I marched out into the street, leaving the man lying on the stairs.”

“And you troubled no more about him?” said Kemp.

“No,” said the Invisible Man. “And I haven’t heard what became of him.”

“What happened when you went out?”

“Oh! Disappointment again. I thought my troubles were over. I thought I could do what I chose, everything. So I thought. Nothing could happen to me, I could take off my clothes and vanish. Nobody could hold me. I could take my money where I found it. I went to a restaurant and was already ordering a lunch, when it occurred to me that I could not eat in public. I finished ordering the lunch, told the man I should be back in ten minutes, and went out exasperated.”

“Then I went to a hotel and asked for a room, where at last I ate my lunch.

“The more I thought it over, Kemp, the more I realised how helpless an Invisible Man was, – in a cold and dirty climate and a crowded, civilised city. Before I made this mad experiment I had thought of a thousand advantages. That afternoon it seemed all disappointment. What was I to do? I had become a bandaged caricature of a man.”

He looked at the window.

“But how did you get to Iping?” said Kemp, who wanted to keep his guest away from the window.

“I went there to work. I hoped to find a way of getting back after I did all I planned while I was invisible. And that is what I want to talk to you about now.”

“You went straight to Iping?”

“Yes, I took my three diaries and my chequebook, my luggage and chemicals. I will show you the calculations as soon as I get my books. Did I kill that constable?”

“No,” said Kemp. “He’s recovering.”

“I lost my temper! Why couldn’t the fools leave me alone? And that man from the shop?”

“He’s recovering, too,” said Kemp.

“Lord, Kemp!… I worked for years, and then some idiots stand in my way! If I have much more of it, I shall go mad, – I shall start killing them.”

Chapter XVIII

The Plan that Failed

“But now,” said Kemp, looking out of the window, “what are we to do?”

He stood near his guest to prevent him from seeing three men who were walking up the hill road.

“What were you planning to do, when you came to Burdock?”

“I was going to get out of the country. I wanted to go to the south where the weather is hot and invisibility possible, to France first, then I could go to Spain, or to Algiers. There a man might be invisible, and yet live. I was using that tramp as a luggage carrier, and then he got an idea to rob me! He has hidden my books, Kemp. Hidden my books! If I find him!…”

“But where is he? Do you know?”

“He’s in the town police station. He asked to lock himself up.”

“Curse him!” said the Invisible Man. “We must get those books!”

“Certainly,” said Kemp, wondering if he heard steps outside. Kemp tried to think of something to keep the talk going.

“When I got into your house, Kemp,” said the Invisible Man, “I changed all my plans. You are a man that can understand. You have told no one I am here?” he asked suddenly.

“No,” Kemp said.

“I made a mistake, Kemp, starting this thing alone. It is wonderful how little a man can do alone!

“What I want, Kemp, is a helper, and a hiding‑place. I must have a partner. With a partner, with food and rest, a thousand things are possible. Invisibility is useful in getting away, in approaching. It’s very useful in killing. I can come up to a man, and strike as I like, and escape.”

Kemp heard a movement downstairs.

“And we must kill, Kemp.”

“I’m listening to your plan, Griffin,” said Kemp, “but I do not agree. Why kill?”

“The Invisible Man will establish a Reign of Terror. Yes; a Reign of Terror. He must take some town, like your Burdock, and terrify and dominate it. He will kill all who is against him.”

Kemp was no longer listening to Griffin, but to the sound of his front door opening and closing.

“Your partner would be in a difficult position,” he said

“No one would know he was my partner,” said the Invisible Man. And then suddenly, “Hush! What’s that downstairs?”

“Nothing,” said Kemp, and suddenly began to speak loud and fast. “I don’t agree to this, Griffin,” he said. “Understand me, I don’t agree to this. How can you hope to be happy? Publish your results. Think what you can do with a million helpers.”

The Invisible Man interrupted. “There are steps coming upstairs. Let me see,” said the Invisible Man, and went to the door.

“Traitor!” cried the Invisible Man