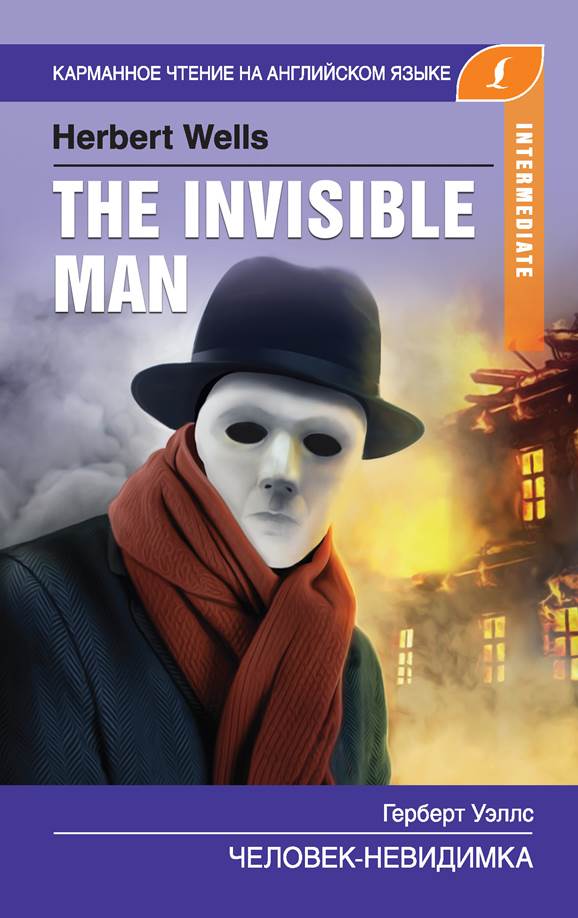

Герберт Джордж Уэллс

Человек‑невидимка / The Invisible Man

Карманное чтение на английском языке –

http://www.litres.ru/pages/biblio_book/?art=48450872

«Человек‑Невидимка / The invisible man»: АСТ; Москва; 2019

ISBN 978‑5‑17‑116890‑2

Аннотация

В книгу вошел сокращенный и незначительно адаптированный текст научно‑фантастического романа Г.Дж. Уэллса «Человек‑невидимка». В данном романе описывается судьба британского учёного‑физика, который изобрёл способ сделать человека невидимым. Текст произведения адаптирован и сопровождается словарем. Предназначается для продолжающих изучать английский язык средней ступени (уровень Intermediate).

Герберт Уэллс / Herbert Wells

Человек‑Невидимка / The invisible man

© Глушенкова Е.В., адаптация текста, словарь

© ООО «Издательство АСТ», 2019

Chapter I

The Strange Man’s Arrival

The stranger came in February, as it was snowing heavily, walking from Bramblehurst Railway Station, and carrying a little black bag. He came into the “Coach and Horses [1] ” more dead than alive. “A fire!” he cried, “A room and a fire!” He shook the snow off himself, and followed Mrs. Hall into her guest room, where he put some sovereigns on the table.

Mrs. Hall lit the fire and left him there while she went to prepare him a meal. A guest to stop at Iping in the winter time was an unheard‑of piece of luck [2], especially a guest who paid in cash.

When lunch was ready, she carried plates, and glasses into the room. She was surprised to see that her visitor still wore his hat and coat, and stood with his back to her and looking out of the window at the falling snow, with his gloved hands behind him.

“Can I take your hat and coat, sir,” she said, “and dry them in the kitchen?”

“No,” he said.

He turned his head and looked at her over his shoulder. “I’ll keep them on,” he said; and she noticed that he wore big blue spectacles and had whiskers. The spectacles, the whiskers, and his coat collar completely hid his face.

“Very well, sir,” she said. “As you like. In a moment the room will be warmer.”

He made no answer, and Mrs. Hall, feeling that it was a bad time for a conversation, quickly laid the table and left the room. When she returned he was still standing there, his collar turned up, his hat hiding his face completely.

She put down the eggs and bacon, and said to him:

“Your lunch is served, sir.”

“Thank you,” he said, and did not turn round until she closed the door.

As she went to the kitchen she saw her help Millie still making mustard. “That girl!” she said. “She’s so long!” And she herself finished mixing the mustard. She had cooked the ham and eggs, laid the table, and done everything, while Millie had not mixed the mustard! And a new guest wanted to stay! Then she filled the mustard‑pot, and carried it into the guest room.

She knocked and entered at once. She put down the mustard‑pot on the table, and then she noticed the coat and hat on a chair in front of the fire. She wanted to take these things to the kitchen. “May take them to dry now?” she asked.

“Leave the hat,” said her visitor in a muffled voice, and turning, she saw he had raised his head and was looking at her.

For a moment she stood looking at him, too surprised to speak.

He held a white napkin, which she had given him, over the lower part of his face, so that his mouth was completely hidden, and that was the reason of his muffled voice. But what surprised Mrs. Hall most was the fact that all the forehead above his blue glasses was covered by a white bandage, and that another bandage covered his ears, so that only his pink nose could be seen. It was bright pink. He wore a jacket with a high collar turned up about his neck. The thick black hair could be seen between the bandages. This muffled and bandaged head was so strange that for a moment she stood speechless. He remained holding the napkin, as she saw now, with a gloved hand. “Leave the hat,” he said, speaking through the napkin.

She began to recover from the shock she had received. She placed the hat on the chair again by the fire. “I didn’t know, sir,” she began, “that –” And she stopped, not knowing what to say.

“Thank you,” he said dryly, looking from her to the door, and then at her again.

“I’ll have them nicely dried, sir, at once,” she said, and carried his clothes out of the room. She shivered a little as she closed the door behind her, and her face showed her surprise.

The visitor sat and listened to the sound of her feet. He looked at the window before he took away the napkin; then rose and pulled the blind down. He returned to the table and his lunch.

“The poor man had an accident, or an operation or something,” said Mrs. Hall. “And he held that napkin over his mouth all the time. Talked through it!… Perhaps his mouth was hurt too.”

When Mrs. Hall went to clear away the stranger’s lunch her idea that his mouth must also have been cut [3] in the accident was confirmed, for he was smoking a pipe, and all the time that she was in the room he held a muffler over the lower part of his face. He sat in an armchair with his back to the window, and spoke now, having eaten and drunk [4], less aggressively than before.

“I have some luggage,” he said, “at Bramblehurst Station,” and he asked her how he could have it sent [5].

Her explanation disappointed him.

“Tomorrow!” he said. “Can’t I have it today?”

“It’s a bad road, sir,” she said, “There was an accident there a year ago. A gentleman killed. Accidents, sir, happen in a moment, don’t they?”

But the visitor did not feel like talking.

“They do,” he said, through his muffler, looking at her quietly from behind his glasses.

“But they take long enough to get well, sir, don’t they? My sister’s son, Tom, once just cut his arm. He was three months bandaged, sir.”

“I can quite understand that,” said the visitor.

“We were afraid, one time, that he’d have to have an operation, he was that bad, sir.”

The visitor laughed suddenly.

“Was he?” he said.

“He was, sir. And it was no laughing matter to them [6], sir –”

“Will you get me some matches?” said the visitor. “My pipe is out.”

Mrs. Hall stopped suddenly. It was certainly rude of him after telling him about her family. She stood for a moment, remembered the sovereigns, and went for the matches. Evidently he did not want to speak about operations and bandages.

The visitor remained in his room until four o’clock. He was quite still during that time: he sat smoking by the fire.

Chapter II

Chapter III

Chapter IV

Mr. Cuss Meets the Stranger

The stranger stayed quietly in Iping until April.

Hall did not like him, and whenever he talked of getting rid of him, Mrs. Hall said “Wait till the summer, when the artists begin to come. Then we’ll see. He may be unpleasant, but pays regularly.”

The stranger did not go to church, he worked, as Mrs. Hall thought, from time to time. Some days he got up early and worked all day. On others he got up late, smoked, or slept in the arm‑chair by the fire. He had no communication with the world. His habit of talking to himself in a low voice grew, but though Mrs. Hall listened near the door she could make neither head nor tail of what she heard [12].

He rarely went out by day, but in the evening he went out muffled up in any weather, and he chose the loneliest places. His spectacles and bandaged face frightened villagers.

It was natural that a person of such an unusual appearance and behaviour was much talked about in Iping. People were curious about his occupation. When asked, Mrs. Hall explained very carefully that he was a scientist, and then said that he “discovered things.” Her visitor had had an accident, she said, which changed the colour of his face and hands, and he was ashamed of it and avoided public attention.

There was also a view that he was a criminal trying to escape from the police. This idea first came to Mr. Teddy Henfrey, but no one knew of a crime from the middle or end of February. Another theory was that the stranger was a terrorist in disguise, preparing explosions. Yet another view was that the stranger a lunatic. But whatever they thought of him, people in Iping disliked him. His irritability made him no friends there.

Cuss, the village doctor, was very curious. The bandages excited his professional interest; the thousand‑and‑one bottles were also of interest to him. He looked for an excuse to visit the stranger, and at last he called on him to collect money for a village nurse. He was surprised that Mr. Hall did not know his guest’s name.

Cuss knocked on the door and entered, and then the door closed and Mrs. Hall couldn’t hear their conversation.

She could hear their voices for the next ten minutes, then a cry of surprise, a chair falling, laughter, quick steps to the door, and Cuss appeared, his face white. He left the inn without looking at her. Then she heard the stranger laughing quietly, the door closed, and all was silent again.

Cuss went straight to Bunting, the vicar.

“Am I mad?” Cuss began at once, as he entered the vicar’s little study. “Do I look mad?”

“What’s happened?” said the vicar.

“That man at the inn –”

“Well?”

“I went in,” he said, “and began to ask for money for the nurse. I spoke of the nurse, and all time looked round. Bottles – chemicals – everywhere. Would he give the money? He said he’d consider it. I asked him if he was doing research. He said he was. A long research? He got very angry, a ‘damnable long research,’ said he. ‘Damn you! What do you want here?’ I apologised. Draught of air from window lifted a paper from the table. He was working in a room with an open fireplace. In a moment I saw the paper burning. The man rushed to the fire and stretched his arm. There was no hand. Just an empty sleeve. Lord! I thought, there’s something odd in that. What keeps that sleeve up and open if there’s nothing in it? There was nothing in it, I tell you. ‘Good God!’ I said. He stared at me, and then at his sleeve.”

“Well?”

“That’s all. He never said a word, just put his sleeve in his pocket. ‘How,’ said I, ‘can you move an empty sleeve like that?’ ‘You saw it was an empty sleeve?’ He came to me, and stood quite close. Then he pulled his sleeve out of his pocket again, and raised his arm towards me. ‘Well?’ said I; ‘there’s nothing in it.’ I could see right down it. And then something struck my nose.”

Bunting began to laugh.

“There wasn’t anything there!” said Cuss. “I was so surprised, I hit his sleeve, and it felt exactly like hitting an arm. And there wasn’t an arm!”

Mr. Bunting thought it over. He looked suspiciously at Cuss. “It’s a most remarkable story,” he said.

Chapter V

Strange Events in Iping

The facts of the burglary at the Vicarage were told by the vicar and his wife. It occurred at night late in April.

Mrs. Bunting woke up suddenly at night, with a strong impression that the door of their bedroom had opened and closed. She then heard the sound of bare feet walking along the passage. She woke up Mr. Bunting, who did not strike a light, but went out of the bedroom to listen. He heard some noise in his study downstairs, and then a sneeze.

He returned to his bedroom, took a poker, and went downstairs as noiselessly as possible. Everything was still, except some noise in the study. Then the study was lit by a candle. Mr. Bunting was now in the hall, and through the door he could see the desk, and a candle on it. But he could not see the burglar. He stood there in the hall not knowing what to do, and Mrs. Bunting, her face white, went slowly downstairs after him.

They heard the chink of money, and realized that the burglar had found the gold – two pounds ten. Gripping the poker firmly, Mr. Bunting rushed into the room, followed by Mrs. Bunting.

The room was empty.

Yet they were certain they had heard somebody moving in the room. For half a minute they stood still, then Mrs. Bunting went across the room and looked under the desk, behind the curtains, and Mr. Bunting looked up the chimney.

“The candle!” said Mr. Bunting. “Who lit the candle?”

“The money’s gone!” said Mrs. Bunting.

There was a sneeze in the passage. They rushed out, and heard the kitchen door close.

“Bring the candle!” said Mr. Bunting. As he opened the kitchen door, he saw the back door just opening, but nobody went out of the door.

It opened, stood open for a moment, and then closed. When they entered the kitchen it was empty. They examined all the house. There was nobody there.

* * *

That morning Mr. Hall and Mrs. Hall both got up early and went to the cellar. Their business there was of a secret nature, and had something to do with their beer.

When they entered the cellar, Mrs. Hall found she had forgotten to bring down a bottle of sarsaparilla [13]. Hall went upstairs for it.

He was surprised to see that the stranger’s door was ajar. He went to his own room and found the bottle.

But as he came downstairs, he noticed that the front door had been unbolted – that the door was, in fact, simply closed. When he saw this, he stopped, then, knocked on the stranger’s door. There was no answer. He knocked again; then opened the door and entered. The room was empty. And what was still odder, on the chair and the bed were all the clothes and the bandages of their guest. Even his big hat was there on the bed.

Hall turned and hurried down to his wife, down the cellar steps.

“He is not in the room. And the front door’s unbolted.”

Mrs. Hall decided to see the empty room for herself. As they came up the cellar steps, they both heard the front door open and shut.

She opened the door and stood looking round the room. She came up to the bed and put her hand on the pillow and then under the clothes.

“Cold,” she said. “He’s been up for an hour or more.”

As she did so a most extraordinary thing happened. The bed‑clothes gathered themselves together, and then jumped off the bed. It was as if a hand had taken and thrown them on the floor. Then the stranger’s hat jumped off the bed, and flew straight at Mrs. Hall’s face. Then the chair, laughing in a voice like the stranger’s, turned itself up and flew at Mrs. Hall. She screamed and turned, and then the chair legs pushed her and Hall out of the room. The door shut and was locked.

“These were spirits,” said Mrs. Hall. “I know these were spirits. I’ve read in papers of them. Tables and chairs flying and dancing … Don’t let him come in again. I should have guessed [14]… With his bandaged head, and never going to church on Sunday. And all the bottles – more than anyone needs. He’s put the spirits into the furniture … My good old furniture!”

Suddenly and most wonderfully the door of the guest room opened, and as they looked up in amazement, they saw the muffled figure of the stranger, staring at them. “Go to the devil!” shouted the stranger. Then he entered his room, and slammed the door in their faces.

Chapter VI

Chapter VII

Mr. Thomas Marvel

Mr. Thomas Marvel was sitting by the roadside about a mile and a half out of Iping. He was looking at a pair of boots. They were the best boots he had had for a long time, but too large for him. Mr. Thomas Marvel hated large boots, but they were really good. He put the boots on the grass, and looked at them. It suddenly occurred to him that they were very ugly.

“They’re boots, anyhow,” said a Voice behind him.

“They are the ugliest pair in the whole world!”

“H’m,” said the Voice.

“ A gentleman on tramp [17] sees a lot of boots. They give you good boots in this county. I’ve got my boots in this county ten years or more. And then they give you something like this.”

“It’s an ugly county,” said the Voice, “and pigs for people [18].”

Mr. Thomas Marvel turned his head over his shoulder first to the right, then to the left to look at the boots of the man he was talking to, but saw neither legs nor boots. He was greatly amazed. “Where are you?” said Mr. Thomas Marvel. He saw nothing but grass and bushes.

“Am I drunk?” said Mr. Marvel. “Have I had visions? Was I talking to myself?”

“Don’t be alarmed,” said the Voice.

“Where are you? Are you buried?” said Mr. Thomas Marvel after an interval.

There was no answer. The road was empty north and south, and the blue sky was empty too.

“It’s the drink,” said Mr. Thomas Marvel.

“It’s not the drink,” said the Voice.

“Oh!” said Mr. Marvel, and his face grew white. “It’s the drink,” he repeated. “ I could have sworn [19] I heard a voice,” he whispered.

“Of course you did.”

“It’s there again,” said Mr. Marvel, closing his eyes with his hands. He was suddenly taken by the collar and shaken violently.

“Don’t be a fool!” said the Voice.

“I’m mad! Or it’s spirits!” said Mr. Marvel.

“Neither mad nor spirits,” said the Voice.

“Listen! You think I’m just imagination?”

“What else can you be?” said Mr. Thomas Marvel.

“Very well,” said the Voice. “Then I’m going to throw stones at you.”

A stone flew through the air and hit Mr. Marvel’s shoulder. Mr. Marvel, turning, saw a stone hang in the air for a moment, and then fall at his feet. Another stone hit his foot. The tramp jumped, and screamed.

“Now,” said the Voice, “am I imagination?”

“I don’t understand it. Stones throwing themselves. Stones talking.”

“It’s very simple,” said the Voice. “I’m an invisible man. That’s what I want you to understand.”

“But where are you?” asked Mr. Marvel.

“Here! Six yards in front of you.”

“Oh, come! I’m not blind.”

“You’re looking through me.”

“What!”

“I am just a man who needs food and drink, clothes, too … But I’m invisible. You see? Invisible. Simple idea. Invisible.”

“What, real?”

“Yes, real.”

“Give me your hand,” said Marvel, “if you are real.”

He felt a hand touch his arm, then his face.

“Most remarkable!” Marvel’s face showed astonishment. “And there I can see a rabbit through you a mile away! Not a bit of you visible – except –”

He looked carefully in front of him. “Have you been eating bread and cheese?” he asked.

“You are quite right. It’s not assimilated into the system.”

“Ah!” said Mr. Marvel. “How did you do it?”

“It’s too long a story. I need help. I saw you suddenly. I was walking, mad with rage, naked, helpless, I could have murdered [20] … And I saw you – ‘Here,’ I said ‘is an outcast like myself. This is the man for me.’ So I turned back and came to you.”

“Lord!” said Mr. Marvel. “But how can I help you?”

“I want you to help me get clothes and shelter, and then with other things. If you won’t –… But you will – must. Help me – and I will do great things for you. An Invisible Man is a man of power.” He stopped for a moment to sneeze violently. “But if you betray me –,” he said.

He touched Mr. Marvel’s shoulder. Mr. Marvel gave a cry of terror at the touch. “I don’t want to betray you,” said Mr. Marvel. “All I want to do is to help you – just tell me what I have to do. I’ll do what you want.”

Chapter VIII

In the “Coach and Horses”

After the first panic was over, Iping became sceptical. It is much easier not to believe in an Invisible Man, and those who had actually seen him vanish in the air or felt the strength of his arm could be counted on the fingers of two hands. By the afternoon even those who believed in the Invisible Man were beginning to forget him.

About four o’clock a stranger entered the village. He was a short person in an extraordinarily shabby hat, and he appeared to be in a hurry [21]. He went to the “Coach and Horses.”

This stranger appeared to be talking to himself, as Mr. Huxter remarked. He stopped at the “Coach and Horses”, and, according to Mr. Huxter, it seemed he did not want to go in. At last he marched up the steps, and Mr. Huxter saw him turn to the left and open the door of the guest room. Mr. Huxter heard voices from the bar telling him of his mistake.

“That room’s private!” said Hall, and the stranger shut the door and went into the bar.

In a few minutes he reappeared. He stood looking about him for some moments, and then Mr. Huxter saw him walk towards the window of the room he had attempted to enter a few minutes before. The stranger took out a pipe, and began to smoke, looking around him carefully.

All this Mr. Huxter saw through the window of his shop, and the man’s suspicious behavior made him continue his observation.

At last the stranger put his pipe in his pocket, looked around, and vanished in the window.

Mr. Huxter ran out into the road to catch the thief. As he did so, Mr. Marvel reappeared, a big bundle in one hand, and three books in the other. As he saw Huxter he turned to the left, and began to run.

“Stop thief!” cried Huxter, and set off after him. He had hardly gone ten steps before he was caught in some mysterious way, and he was no longer running but flying through the air. He saw the ground suddenly close to his head, and all went black.

* * *

To understand what had happened in the inn, it is necessary to go back to the moment when Mr. Huxter first saw Mr. Marvel through the window.

At that moment Mr. Cuss and Mr. Bunting were in the guest room. They were seriously investigating what had happened in the morning, and were, with Mr. Hall’s permission, making a thorough examination of the Invisible Man’s things. Jaffers had recovered from his fall and had gone home. The stranger’s clothes had been taken away by Mrs. Hall, and the room tidied up. And on the table under the window, where the stranger had usually worked, Cuss had almost at once found three big books labeled

“Diary.”

“Diary!” said Cuss, putting the three books on the table. “Now we shall learn something. H’m – no name. Cipher. And figures.”

Cuss turned the pages over with a face suddenly disappointed. “It’s all cipher, Bunting.”

“There are no diagrams?” asked Mr. Bunting.

“No illustrations?”

“No,” said Mr. Cuss. “Some of it’s mathematical, and some of it’s Russian or some other language –”

The door opened suddenly.

Both men looked round, and saw a tramp.

“Bar?” asked he.

“No,” said both gentlemen at once. “Over the other side.”

“All right,” said the man in a low voice, different from the first question and closed the door.

“And now,” Mr. Bunting said, “these books.”

“One minute,” said Cuss, and went and locked the door. “Now I think we are safe from interruption.”

Someone sneezed as he did so.

“Very strange things have happened in Iping during the last few days – very strange. I cannot, of course, believe in the Invisible Man –” said Bunting.

“It’s incredible,” said Cuss, “incredible. But the fact remains that I saw – I certainly saw right down his sleeve –”

“But did you – are you sure… Hallucinations may be…”

Suddenly Mr. Bunting had a strange feeling at the back of his neck. He tried to move his head, and could not. The feeling was a grip of a heavy, firm hand. “Don’t move, little men,” whispered a voice, “or I’ll kill you both!” He looked into the face of Cuss, close to his own, and saw astonishment in it.

“Since when did you learn to pry into private papers?” said the Voice, and two chins struck the table.

“Since when did you learn to enter private rooms?” and the concussion was repeated. “Where have they put my clothes? Listen,” said the Voice. “I am a strong man, and I could kill you both and get away quite easily if I wanted to – do you understand? Very well. If I let you go, will you promise to do what I tell you?”

“Yes,” said Mr. Bunting, and the doctor repeated it. Then the pressure on the necks relaxed, and the doctor and vicar sat up, both very red in the face.

“When I came into this room, I expected to find my diary and clothes,” said the Invisible Man. “Where are they? My clothes are gone. I want clothes – and I must also have those three books.”

Chapter IX

The Invisible Man Returns

While these things were going on, and while Mr. Huxter was watching Mr. Marvel smoking his pipe outside, Mr. Hall and Teddy Henfrey were discussing the only topic that interested Iping. Suddenly they heard some noise in the guest room, a cry, and then – silence.

Mr. Hall understood things slowly but surely. “That isn’t right,” he said, and came towards the door of the guest room. Teddy followed him.

“Something is wrong,” said Hall, and Henfrey nodded agreement. There was a muffled sound of conversation in the room.

“You all right, sir?” asked Hall, knocking.

The muffled conversation stopped, for a moment silence, then a cry of “No! you don’t!”

There came sounds of struggle. Silence again.

“You – all – right – sir?” asked Mr. Hall again.

The vicar’s voice answered with a curious intonation. “Quite ri‑ight. Please don’t – interrupt.”

“Odd!” said Mr. Henfrey.

“Odd!” said Mr. Hall.

“Says, ‘Don’t interrupt,’” said Henfrey.

“I heard,” said Hall.

They remained listening, but couldn’t hear what the conversation was about. The sounds in the room were very odd.

Mrs. Hall appeared behind the bar. They all stood listening. Mrs. Hall was looking through the inn door, and saw the road and Huxter’s shop. Suddenly Huxter’s door opened, and Huxter appeared.

“Stop thief!” cried Huxter, ran down the road, and vanished.

At the same time they heard some noise from the guest room, and a sound of a window closing. All who were in the bar rushed out at once into the street. They saw Mr. Huxter jump in the air and fall on his face. Mr. Huxter was thrown on the ground. Hall saw Mr. Marvel vanishing round the corner of the church wall. He thought that this was the Invisible Man suddenly become visible, and ran after him. But Hall had hardly run a few yards before he gave a loud shout of astonishment [22] and went flying in the air. He hit on the running men, bringing them to the ground. A few people running after Mr. Marvel were also knocked with violent blows to the ground.

When Hall and Henfrey and the others ran out of the house, Mrs. Hall remained in the bar. And suddenly the guest room door was opened, and Mr. Cuss appeared and rushed at once out. “Hold him!” he cried, “don’t let him drop that bundle! You can see him as long as he holds the bundle.”

He knew nothing of Marvel. The Invisible Man had given him the books and bundle through the window. The face of Mr. Cuss was angry.

“Hold him!” he cried. “He’s got my trousers! – and all the vicar’s clothes!” He ran past Huxter lying on the ground, and was knocked off his feet. Mr. Cuss rose, and was hit again. Behind him he heard a sudden yell of rage. He recognized the voice of the Invisible Man. In another moment Mr. Cuss was back in the inn.

“He’s coming back, Bunting!” he said, rushing in. “Save yourself!”

Mr. Bunting stood trying to clothe himself in newspapers.

“Who’s coming?” he said.

“Invisible Man!” said Cuss, and rushed to the window. “We’d better get out from here. He’s fighting mad! Mad!”

In another moment he was out.

“Lord!” said Mr. Bunting, hesitating between two horrible alternatives. He heard a struggle in the passage of the inn, and made a decision.

He jumped out of the window, pressing newspapers to his body, and ran away as fast as his fat little legs could carry him.

All villagers ran for their houses and locked themselves up. The Invisible Man, mad with rage, broke all the windows in the “Coach and Horses”. And after that, he was neither heard, seen, nor felt in Iping any more. He vanished absolutely.

Chapter X

Mr. Marvel Escapes

When it was getting dark, a man in a shabby hat was marching on the road to Bramblehurst. He carried three books, and a bundle. He was accompanied by a Voice and seemed to be beaten by unseen hands.

“If you give me the slip [23] again,” said the Voice;

“if you attempt to give me the slip again –”

“Lord!” said Mr. Marvel. “Don’t touch my shoulder. It hurts.”

“I will kill you,” said the Voice.

“I didn’t try to give you the slip,” said Marvel, with tears in his voice. “I swear I didn’t. I didn’t know the way, that was all!”

“It’s bad that my secret is known, without your escaping with my books. No one knew I was invisible! And now what am I to do?”

“What am I to do?” asked Marvel.

“It will be in the papers! Everybody will be looking for me.”

The Voice swore. Mr. Marvel grew even more desperate, and he stopped.

“Go on. You’re a poor tool, but I shall have to use you,” said the Voice sharply.

“I’m a miserable tool,” said Marvel.

“You are,” said the Voice.

“I’m the worst possible tool you could have,” said Marvel. “I’m not strong.”

“No?”

“And my heart’s weak. I wish I was dead,” said Marvel. “I tell you, sir, I’m not the man for it.”

“Shut up,” said the Invisible Man. “I want to think.”

They were coming to a village.

“I shall keep my hand on your shoulder,” said the Voice, “all through this village. Go straight and try no foolery [24]. It will be the worse for you [25] if you do.”

“I know that,” said Mr. Marvel, “I know all that.”

The unhappy‑looking figure walked through the little village, and vanished into the darkness in the direction of a small town Port Stowe.

* * *

The “Jolly Cricketers [26] ” is in Burdock just at the bottom of the hill, on the road from Port Stowe. The barman talked of horses with a cabman, while a black‑bearded man was eating biscuit and cheese, drank beer, and talked with a policeman.

“What’s the matter?” said the cabman. Somebody ran by outside.

Footsteps approached, the door opened violently, and Marvel, his hat gone, the collar of his coat torn, rushed in, and attempted to shut the door.

“Coming!” he shrieked with terror. “He’s coming. The Invisible Man! After me. For God’s sake [27]! Help! Help!”

“Shut the doors,” said the policeman. “Who’s coming? What’s the matter?” He went to the door and bolted it.

“Lock me in – somewhere,” said Marvel. “He’s after me. I gave him the slip. He said he’d kill me, and he will.”

“You’re safe,” said the man with the black beard. “The door’s shut. What’s it all about?”

A blow suddenly made the bolted door shiver, and was followed by other blows and shouting outside.

“Who’s there?” cried the policeman.

“He’ll kill me – he’s got a knife or something. For God’s sake –!” Mr. Marvel shrieked.

“Come in here,” said the barman. Mr. Marvel rushed behind the bar. “Don’t open the door,” he screamed. “Please don’t open the door.”

“Is this the Invisible Man, then? Newspapers are full of him,” said the man with the black beard.

The window of the inn was suddenly smashed, and there was screaming and running to and fro in the street.

“If we open, he will come in. There’s no stopping him [28],” said the policeman.

“If he comes–,” said the man with the black beard, holding a revolver in his hand.

“ That won’t do [29],” said the policeman, “that’s murder.”

“I’m going to shoot at his legs,” said the man with the beard.

“Are all the doors of the house shut?” asked Marvel.

“Lord!” said the barman. “There’s the back door!”

He rushed out of the bar. In a minute he returned.

“The back door was open,” he said.

“He may be in the house now,” said the cabman.

Just as he said so they heard Marvel shriek.

They saw Marvel struggling against something unseen. Then he was dragged to the back door, head down.

The policeman rushed to him, followed by the cabman, gripped the invisible hand that held Marvel, was hit in the face and fell. Then the cabman gripped something. “I got him,” said the cabman. Mr. Marvel was released, suddenly dropped to the ground, and crawled behind the legs of the fighting men to the door. The voice of the Invisible Man was heard for the first time, he cried as the policeman stepped on his foot.

The struggle went on, and no one saw Mr. Marvel slip out of the door and run away. He left the back door open behind him, and in a moment thecrowd of fighting men was outside.

“Where’s he?” cried the policeman, stopping.

A stone flew by his head.

“I’ll show him,” shouted the man with the black beard, and shot five times.

A silence followed. “ Come and feel about for his body [30],” said the man with the black beard.

Chapter XI

The Invisible Man is Coming

In the early evening Dr. Kemp was sitting in his study in the house on the hill overlooking Burdock. It was a pleasant room, with three windows and bookshelves with books and scientific publications, and a writing‑table, and under the window a microscope, some cultures, and bottles of reagents.

Dr. Kemp was a tall young man, with hair almost white, and the work he was doing would earn him, he hoped, the fellowship of the Royal Society [31].

For a minute, perhaps, he sat looking out at the hill, and then his attention was attracted by the figure of a man, running over the hill towards him.

“Another of those fools,” said Dr. Kemp.

“Like that fool who ran into me this morning round a corner, with his ‘Invisible Man’s coming, sir!’ One might think [32] we were in the thirteenth century.”

He got up, went to the window, and stared at the hillside and the figure running down it.

“Fools!” said Dr. Kemp, walking back to his writing‑table.

Dr. Kemp continued writing in his study until he heard shots. Crack, crack, crack, they came one after the other.

“Who’s shooting in Burdock?” said Dr. Kemp listening.

He went to the window, and looked down. He saw a crowd by “The Cricketers”, and watched.

After five minutes, Dr. Kemp returned to his writing desk.

About an hour after this the front door bell rang. He heard the servant answer the door, and waited for her, but she did not come.

“What was that?” said Dr. Kemp.

He went downstairs from his study, and saw the servant. “Was that a letter?” he asked.

“There was nobody at the door, sir,” she answered.

Soon he was hard at work again, and he worked till two o’clock. He wanted a drink, so he took a candle and went down to the dining‑room for whisky.

Dr. Kemp’s scientific investigations had made him a very observant man, and as he crossed the hall he noticed a dark spot on the floor. He put down the whisky, bent, and touched the spot. It felt like drying blood.

He returned upstairs looking about him and thinking of the blood spot. Upstairs he saw something, and stopped astonished. There was blood on the door‑handle of his room.

He looked at his own hand. It was quite clean, and then he remembered that the door of his room had been open when he came from his study, and he had not touched the handle at all. He went straight into his room. There was blood on his bed, and the sheet had been torn. On the farther side the bedclothes were depressed as if someone had been sitting there.

Then he heard a low voice say, “Lord! – Kemp!” But Dr. Kemp did not believe in voices.

He stood staring at the blood on his sheets. Was that really a voice? He looked about again, but noticed nobody. Then he heard a movement across the room. He put down his whisky on the dressing‑table. Suddenly, he saw a blood‑stained bandage hanging in the air, near him. He stared at this in amazement. It was an empty bandage – a tied bandage, but quite empty.

“Kemp!” said the Voice, quite close to him. “I am an Invisible Man.”

Kemp was not very much frightened or very greatly surprised at the moment. He did not realise it was true. “I thought it was all a lie,” he said. “Have you a bandage on?”

“Yes,” said the Invisible Man.

“Oh!” said Kemp. “But this is nonsense. It’s some trick.” He wanted to touch the bandage, and his hand met invisible fingers. The hand gripped his arm. He struck at it.

“ Keep steady [33], Kemp, for God’s sake! I want help badly. Stop! Kemp, keep steady!” cried the Voice.

Kemp opened his mouth to shout, and the corner of the sheet was put between his teeth. The Invisible Man pushed him down on the bed.

“Lie still, you fool!” said the Invisible Man in Kemp’s ear.

Chapter XII

Dr. Kemp’s Visitor

Kemp struggled for another moment, and then lay still.

“If you shout, I’ll smash your face,” said the Invisible Man. “I’m an Invisible Man. It is no trick and no magic. I am really an Invisible Man. And I want your help. Don’t you remember me, Kemp? Griffin, of University College. I have made myself invisible. I am just an ordinary man, a man you have known.”

“Griffin?” said Kemp.

“Griffin,” answered the Voice. “A younger student than you were, an albino, six feet high, with a pink and white face and red eyes, who won the medal for chemistry.”

Kemp thought. “It’s horrible,” he said.

“Yes, it’s horrible. But I’m wounded and in pain, and tired… Kemp, give me some food and drink.”

Kemp stared at the bandage as it moved across the room, then saw a chair dragged along the floor to the bed. The seat was depressed.

“Give me some whisky. I’m near dead.”

“It didn’t feel so. Where are you? Whisky … Where shall I give it you?”

Kemp felt the glass taken away from him. It hung in the air twenty inches above the chair.

He stared at it in amazement.

“This is – this must be – hypnotism. I demonstrated this morning,” began Kemp, “that invisibility is –”

“ Never mind [34] what you’ve demonstrated! I’m hungry,” said the Voice, “and the night is cold to a man without clothes.”

“Hungry?” said Kemp.

“Yes,” said the Invisible Man, drinking whisky. “Have you got a dressing‑gown?”

Kemp walked to a wardrobe, and took out a dressing‑gown. It was taken from him. It hung for a moment in the air, stood, and sat down in his chair.

“This is the insanest thing I’ve ever seen in my life!”

Kemp went downstairs to look for food. He came back with some cold cutlets and bread, and put them on a small table before his guest. A cutlet hung in the air with a sound of chewing.

“It was my good luck that I came to your house when I was looking for bandages. And it’s my bad luck that blood shows, isn’t it? Gets visible as it coagulates. I’ve changed only the living tissue, and only for as long as I’m alive … I’ve been in the house three hours.”

“But how’s it done?” began Kemp, in a tone of exasperation. “The whole business – it’s insane from beginning to end.”

“Quite sane,” said the Invisible Man; “perfectly sane.”

“How did the shooting begin?” he asked.

“There was a fool – a help of mine, curse him! – who has stolen my money. Moreover, he has stolen my diaries. We stopped at an inn in Port Stowe, a few miles from here. And he gave me the slip with my money and my diaries in the morning, before I got up.”

“Is he invisible, too?”

“No.”

“You didn’t do any shooting?” Kemp asked.

“Not me,” said his visitor. “Some fool I’d never seen.”

After he had done eating, the Invisible Man demanded a cigar. It was strange to see him smoking: his mouth and throat, and nose became visible as smoke filled them.

“ I’m lucky to have met you [35], Kemp. You haven’t changed much. I must tell you. We will work together!”

“But how was it all done?” said Kemp.

“For God’s sake let me smoke, and then I will begin to tell you.”

But the story was not told that night. The Invisible Man’s hand was growing painful; he was too tired. He spoke of Marvel, his voice grew angry.

“He was afraid of me – I could see he was afraid of me,” said the Invisible Man many times. “He wanted to give me the slip from the very start! I was furious. I should have killed him [36] – I haven’t slept for three days, except a couple of hours or so. I must sleep now.”

“Well, sleep in my room.”

“But how can I sleep? How I want to sleep!”

“Why not?”

“Because I don’t want to be caught while I sleep,” he said slowly.

Kemp stared at him.

“What a fool I am!” said the Invisible Man.

“I’ve put the idea into your head.”

Chapter XIII

The Invisible Man Sleeps

“I’m sorry,” said the Invisible Man, “if I cannot tell you all what I have done to‑night. I am tired. I have made a discovery. I wanted to keep it to myself. I can’t. I must have a partner. And you… We can do such things… But tomorrow.”

Kemp stood staring at the headless dressinggown.

“It’s incredible,” he said. “But it’s real!

Good‑night,” said Kemp.

Suddenly the dressing‑gown walked quickly towards him.

“No attempts to catch me! Or –” said the dressing‑gown.

Kemp’s face changed a little. “I thought you called me a partner,” he said.

Kemp closed the door behind him, and the key was turned upon him. “Am I dreaming? Has the world gone mad, or have I?” Kemp said. “Locked out of my own bedroom!” He shook his head hopelessly, and went downstairs to his consulting‑room, and began walking to and fro.

“Invisible!” he said. “Is there such a thing as an invisible animal?… In the sea – yes. Thousands – millions! In the sea there are more things invisible than visible! I never thought of that before… And in the ponds too! All those little things in ponds – bits of colourless jelly!… But in air! No! It can’t be. But after all – why not?”

He took the morning paper, and read the account of a “Strange Story from Iping”.

“He wore a diguise!” said Kemp. “He was hiding! No one knew what had happened to him.”

He took the St. James’s Gazette, opened it, and read: “A Village in Sussex [37] Goes Mad”.

“Lord!” said Kemp, reading an account of the events in Iping. “Ran through the streets striking right and left. Mr. Jaffers and Mr. Huxter in great pain – still unable to describe what they saw. Vicar in terror. Windows smashed.”

He dropped the paper and stared in front of him, then re‑read the article.

“He’s not only invisible,” he said, “but he’s mad!”

He was too excited to sleep that night. In the morning he gave the servant instructions to lay breakfast for two in the study. The morning’s paper came with an account of remarkable events in Burdock. Kemp now knew what had happened at the “Jolly Cricketers”. It seems like rage growing to mania! What can he do! And he’s upstairs free as the air. “What ought I to do?” he said.

He wrote a note, and addressed it to “Colonel Adye, Burdock.”

The Invisible Man woke up as Kemp was doing this. He awoke in a bad temper, and Kemp heard a chair knocked over and a glass smashed.

Kemp hurried upstairs.

“What’s the matter?” asked Kemp, when the Invisible Man opened the door.

“Nothing,” was the answer.

“But the smash?”

“Fit of temper,” said the Invisible Man.

“You often have them.”

“I do.”

“All the facts are out about you,” said Kemp.

“All that happened in Iping and down the hill. The world knows of the invisible man. But no one knows you are here.”

The Invisible Man swore.

“The secret’s out. I don’t know what your plans are, but, of course, I’ll help you. There’s breakfast in the study,” said Kemp, speaking as easily as possible.

Chapter XIV

Certain First Principles

“Before we can do anything else,” said Kemp at breakfast, “I must understand a little more about this invisibility of yours.” He had sat down, after one nervous look out of the window.

“It’s simple,” said Griffin.

“No doubt to you, but –” Kemp laughed.

“Well, to me it seemed wonderful at first. You know I dropped medicine and took up physics? Well, I did. Light interested me. I had hardly worked for six months before I found a general principle of pigments and refraction – a formula. It was an idea how to lower the refractive index of a substance, solid or liquid, to that of air, and so to make it invisible.”

“That’s odd!” said Kemp. “But still I don’t quite see …”

“You know quite well that either a body absorbs light or it reflects or refracts it,” said Griffin. “If it neither reflects or refracts nor absorbs light, it cannot be visible. You see a red box, for example, because the colour absorbs some of the light and reflects the rest, all the red part of the light to you. If it did not absorb any part of the light, but reflected it all, then it would be a shining white box. A diamond box would neither absorb much of the light nor reflect much from the surface, but just here and there the light would be reflected and refracted, so that you would see some brilliant reflections. A glass box would not be so brilliant, not so clearly visible as a diamond box, because there would be less refraction and reflection. See that? From certain points you would see quite clearly through it. Some kinds of glass would be more visible than others. A box of very thin glass would be hard to see in a bad light, because it would absorb hardly any light and refract and reflect very little. And if you put a sheet of glass in water, it would almost vanish, because light passing from water to glass is only a little refracted or reflected. It is almost as invisible as any gas in air.”

“Yes,” said Kemp, “Any schoolboy nowadays knows all that.”

“And here is another fact any schoolboy will know. If a sheet of glass is smashed and beaten into a powder, it becomes much more visible while it is in the air. This is because light is refracted and reflected from many surfaces of the powdered glass. In the sheet of glass there are only two surfaces, in the powder the light is reflected or refracted by each piece it passes through. But if the powdered glass is put into water it vanishes. The powdered glass and water have much the same refraction index, that is, the light is very little refracted or reflected in passing from one to the other.

“The powdered glass might vanish in air, if its refraction index could be the same as that of air. Then there would be no refraction or reflection as the light passed from glass to air.”

“Yes, yes,” said Kemp. “But a man’s not powdered glass!”

“No,” said Griffin. “He’s more transparent!”

“Nonsense!”

“Have you already forgotten your physics in ten years? Just think of all the things that are transparent and seem not to be so! Paper, for example, is made of transparent fibres, and it is white and visible for the same reason that a powder of glass is white and visible. If you oil white paper, so that there is no longer refraction or reflection except at the surfaces, it becomes as transparent as glass. And not only paper, but bone, Kemp, flesh, hair, and nerves; in fact, the whole man, except the red of his blood and the dark pigment of hair, are all made of transparent, colourless tissue. Most fibres of a living tissue are no more visible than water.”

“Of course!” cried Kemp. “I was thinking only last night of the sea jelly‑fish!”

“Yes! And I knew all that a year after I left London – six years ago. But I kept it to myself. Oliver, my professor, was a thief of ideas! And you know the system of the scientific world. I went on working, I did not publish anything, I got nearer and nearer making my formula into an experiment – a reality. I told no one, because I wanted to become famous. I took up the question of pigments, and suddenly – by accident – I made a discovery in physiology.”

“Yes?”

“You know the red substance of blood – it can be made white – colourless!”

Kemp gave a cry of amazement.

“I remember that night. It was late at night. It came suddenly into my mind. I was alone, the laboratory was still … ‘An animal – a tissue – could be made transparent! It could be made invisible! All except the pigments. I could be invisible,’ I suddenly realized what it meant to be an albino with such knowledge. ‘I could be invisible,’ I said.

“I thought of what invisibility might mean to a man. The power, the freedom. I didn’t see any drawbacks.

“And I worked three years, with the professor always watching me. And after three years of secrecy and trouble, I found that to finish it was impossible.”

“Why?” asked Kemp.

“Money,” said the Invisible Man. “I robbed the old man – robbed my father. The money was not his, and he shot himself.”

For a moment Kemp sat in silence, then struck by a thought, he rose, took the Invisible Man’s arm, and turned him away from the window.

“You are tired,” he said, “and while I sit you walk about. Have my chair.”

He stood between Griffin and the window.

“It was last December,” Griffin said. “I took a room in London, in a big house near Great Portland Street. I had bought apparatus with my father’s money, and the work was going on successfully.

“Suddenly I learned of my father’s death. I went to bury him. My mind was still on this research, and I did not lift a finger to save his reputation. I remember the funeral, the cheap ceremony, and the old college friend of his. I did not feel a bit sorry for my father. He seemed to me foolishly sentimental. His funeral was really not my business. It was all like a dream. As I came home, in my room there were the things I knew and loved, my apparatus, my experiments.”

Chapter XV

The Experiment

“I will tell you, Kemp, later about all the processes. We need not go into that now. They are written in cipher in those books that tramp has hidden. We must find him. We must get those books again. I was to put a thing whose refractive index was to be lowered, between two centres of vibration. My first experiment was with a bit of white wool. It was the strangest thing in the world to see it become transparent and vanish.

“And then I heard a miaow, and saw a white cat outside the window. A thought came into my head. ’Everything is ready for you,’ I said, and went to the window, and called her. She came in. The poor animal was hungry – and I gave her some milk.”

“And you processed her?”

“Yes. I gave her some drugs. And the process failed.”

“Failed?”

“The pigment at the back of the eye didn’t go. I put her on the apparatus. And after all the rest had vanished, two little ghosts of her eyes remained. She miaowed loudly, and someone came knocking. It was an old woman from downstairs, who suspected me of vivisecting. I applied some chloroform, and answered the door. ‘Did I hear a cat?’ she asked. ‘Not here,’ said I, very politely. She looked past me into the room. She was satisfied at last, and went away.”

“How long did it take?” asked Kemp.

“Three or four hours – the cat. The bones and nerves and the fat were the last to go, and the back of the eye didn’t go at all.

“About two the cat woke up and began miaowing. I remember the shock I had – there were just her eyes shining green – and nothing round them. She just sat and miaowed at the door. I opened the window and let her out. I never saw nor heard any more of her.

“I thought of the fantastic advantages an invisible man would have in the world.

“But I was tired and soon went to sleep. When I woke up, someone was knocking at the door. It was my landlord. The old woman had said I vivisected her cat. The laws of this country, he said, were against vivisection. And the vibration of my apparatus could be felt all over the house, he said. That was true. He walked round me in the room, looking around him. I tried to keep between him and the apparatus, and that made him more curious. What was I doing? Was it legal? Was it dangerous? Suddenly I had a fit of temper. I told him to get out. He began to protest. I had him by the collar, threw him out, and locked the door.

“This brought matters to a crisis. I did not know what he would do, I could not move to any other rooms, I had only twenty pounds left. Vanish!

“I hurried out with my three books of notes, my cheque book – the tramp has them now – and sent them from the nearest Post Office to myself to another Post Office in Great Portland Street.

“It was all done that evening and night. While I was still sitting under the affect of the drugs that decolourise blood, there came a knocking at the door. I rose, and opened the door. It was the landlord. He saw something odd about my hands, and looked in my face.

“For a moment he stared. Then he gave a cry, and ran to the stairs. I went to the looking‑glass. Then I understood his terror… My face was white – like white stone.

“But it was horrible. I was in pain. I understood now why the cat had miaowed until I chloroformed it. At last the pain was over. I shall never forget the strange horror of seeing my body becoming transparent, the bones and arteries vanishing.

“I was weak and very hungry. I went and stared in my looking‑glass – at nothing, but some pigment of my eyes. I dragged myself back to the apparatus, and finished the process.

“I slept till midday, when I heard knocking. I felt strong again. I listened and heard a whispering. I got up, and as noiselessly as possible began to destroy the apparatus. There was knocking again and voices called, first my landlord’s and then two others. Someone tried to break the lock. But the bolts stopped him.

“I stepped out of the window on to the window‑sill, and sat down, invisible, but trembling with anger, to watch what would happen. They broke the door and rushed in. It was the landlord and his two sons. Behind them was the old woman from downstairs.

“You may imagine their astonishment at finding the room empty. One of the young men rushed to the window at once, and looked out.

His face was a foot from my face. He stared right through me. The old man went and looked under the bed. I sat outside the window and watched them.

“It occurred to me that if a well‑educated person saw my unusual radiators, they would tell him too much. I got into the room, and smashed both apparatus. How scared they were!…

Then I slipped out of the room and went downstairs.

“I waited until they came down. As soon as they had gone to their rooms, I slipped up with a box of matches, and fired my furniture –”

“You fired the house?” said Kemp.

“Yes, I fired the house! I was only just beginning to realise the extraordinary advantage my invisibility gave me.”

Chapter XVI

New Life Begins

“As I got on Great Portland Street, I was hit violently behind, and turning, saw a boy carrying a box of bottles. His astonishment was so funny that I laughed aloud. I took the box out of his hands, and threw it up into the air.

“A few people crowded around us. I realized what I had done. In a moment the crowd would be all around me, and I should be discovered. I pushed by a boy, ran across the road, and soon reached Oxford Street.

“In a moment someone stepped on my foot. I felt very cold. It was a bright day in January, and I was naked, and the mud on the road was freezing. I had not thought that, transparent or not, I should be cold.

“Then an idea came into my head. I jumped into an empty cab. And so, cold and scared, I drove along Oxford Street. I was not feeling as happy and powerful as I had when leaving my house a few minutes before. This invisibility, indeed! My one thought was how to get out of trouble.

“A woman stopped my cab, and I jumped out just in time to escape her. I was now very cold, and felt so unhappy that I cried as I ran.

“A little white dog ran up to me, nose down. I had never realised it before, how dangerous a dog could be for me. He began barking, showing that he felt me. I ran on and on until I saw a big crowd.

“I ran up the steps of a house, and stood there until the crowd had passed. Happily the dog stopped, too, then ran away.

“Two boys stopped at the steps near me. ’Do you see bare footmarks?’ said one.

“I looked down and saw the boys staring at the muddy footmarks I had left on the steps.

‘A barefoot man has gone up the steps,’ said one. ‘And he hasn’t come down.’

“‘Look there, Ted,’ said one of the young detectives, and pointed at my feet. I looked down and saw a silhouette of my muddy feet.

“‘Why, it’s just like the ghost of a foot, isn’t it?’ He stretched out his hand. A man stopped to see what he was catching, and then a girl. In another moment he would have touched me [38]. Then I made a step, and jumped over onto the steps of the next house. But the smaller boy saw the movement.

“‘What’s the matter?’ asked someone.

“‘Feet! Look!’

“In another moment I was running, with six or seven astonished people following my footmarks. I ran round corners and across roads, and then as my feet grew hot I cleaned them with my hands. I did not leave footmarks any more.

“This running warmed me, but I had cut my foot, and there was blood on it. It began snowing. And every dog was a terror to me.”

* * *

“So last January I began this new life. I had no home, no clothes, no one in the whole world whom I could ask for help. I had to get out of the snow, to get myself clothes, then I could make plans. I could see before me – the cold, the snowstorm and night.

“And then I had a good idea. I went to a big department store, where you can find everything: meat, furniture, clothes.

“I did not feel safe there, however, people were going to and fro, and I walked about until I came upon a big furniture section. I found a resting‑place, and I decided to remain in hiding until closing time. Then I should be able, I thought, to find food and clothes and disguise, perhaps sleep on a bed. My plan was to get clothes, money, and then my books at the Post Office, to stay somewhere, and realise the advantages of my invisibility (as I still imagined).

“Closing time arrived quickly. My first visit was to the clothes section, where I found what I wanted – trousers, socks, a jacket, a coat, and a hat. I began to feel man again, and my next thought was food.

“Upstairs was a restaurant, and t