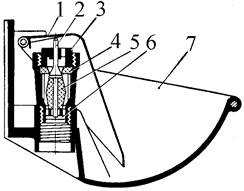

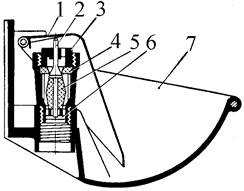

Индивидуальные и групповые автопоилки: для животных. Схемы и конструкции...

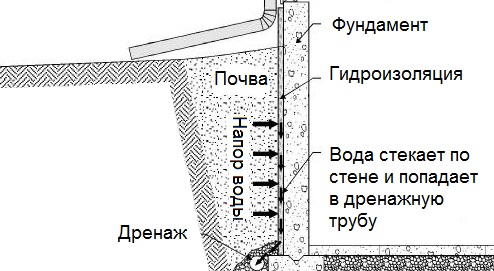

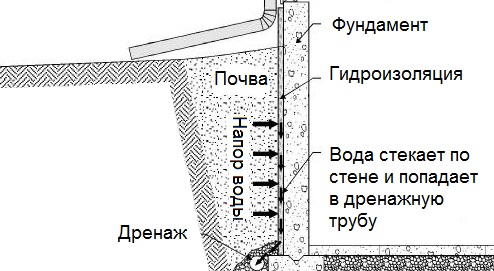

Общие условия выбора системы дренажа: Система дренажа выбирается в зависимости от характера защищаемого...

Индивидуальные и групповые автопоилки: для животных. Схемы и конструкции...

Общие условия выбора системы дренажа: Система дренажа выбирается в зависимости от характера защищаемого...

Топ:

Организация стока поверхностных вод: Наибольшее количество влаги на земном шаре испаряется с поверхности морей и океанов...

История развития методов оптимизации: теорема Куна-Таккера, метод Лагранжа, роль выпуклости в оптимизации...

Особенности труда и отдыха в условиях низких температур: К работам при низких температурах на открытом воздухе и в не отапливаемых помещениях допускаются лица не моложе 18 лет, прошедшие...

Интересное:

Национальное богатство страны и его составляющие: для оценки элементов национального богатства используются...

Берегоукрепление оползневых склонов: На прибрежных склонах основной причиной развития оползневых процессов является подмыв водами рек естественных склонов...

Распространение рака на другие отдаленные от желудка органы: Характерных симптомов рака желудка не существует. Выраженные симптомы появляются, когда опухоль...

Дисциплины:

|

из

5.00

|

Заказать работу |

Содержание книги

Поиск на нашем сайте

|

|

|

|

In this mode the story gets told solely, or at least primarily, as an address by the narrator to someone he calls by the second-person pronoun "you." This form of narration occurred in occasional passages of traditional fiction, but has been exploited in a sustained way only during the latter part of the twentieth century and then only rarely; the effect is of a virtuoso performance. The French novelist Michel Butor, in La Modification (1957, trans. as Second Thoughts, 1981), the Italian novelist Italo Calvino in If on a Winter's Night a Traveler (trans, 1981), and the American novelist Jay Mclnerney in Bright Lights, Big City (1984), all tell their story with "you" as the narratee. Mclnerney's Bright Lights, Big City, for example, begins:

You are not the kind of guy who would be at a place like this at this time of the morning. But here you are, and you cannot say that the terrain is entirely unfamiliar, though the details are fuzzy. You are at a nightclub talking to a girl with a shaved head. The club is either Heartbreak or the Lizard lounge.

This second person may turn out to be a specific fictional character, or the reader of the story, or even the narrator himself or herself, or not clearly or consistently the one or the other; and the story may unfold by shifting between telling the narratee what he or she is now doing, has done in the past, or will or is commanded to do in the future. Italo Calvino uses the form to achieve a complex and comic form of involuted fiction, by involving "you," the reader, in the fabrication of the narrative itself. His novel opens:

You are about to begin reading Italo Calvino's new novel, If on a winter's night a traveler. Relax. Concentrate... Best to close the door, the TV is always on in the next room. Tell the others right away, "No, 1 don't want to watch TV!"... Or if you prefer, don't say anything; just hope they'll leave you alone.

Refer to Brian Richardson; "The Poetics and Politics of Second-Person Narrative," Genre 24 (1991); Monika Fludernick, "Second-Person Narrative as a Test Case for Narratology," Style 28 (1994); and "Second-Person Narrative: A Bibliography," Style (1994); Bruce Morrissette, "Narrative 'You' in Contemporary Literature," Comparative Literature Studies 2 (1965). Scan Matthew Andrews analyzes tactics of second-person narrative in short stories by Lorrie Moore, Frederick Barthelme, and Reynold Price in A Disquisition on Second Person Narrative, Senior Honors Thesis in English at the Pennsylvania State University, 1996.

Two other frequently discussed narrative tactics are relevant to a consideration of points of view:

The self-conscious narrator shatters any illusion that he or she is telling something that has actually happened by revealing to the reader that the narration is a work of fictional art, or by flaunting the discrepancies between its patent fictionality and the reality it seems to represent. This can be done either seriously (Henry Fielding's narrator in Tom Jones and Marcel in Marcel Proust's Remembrance of Things Past, 1913–27) or for primarily comic purposes (Tristram in Laurence Sterne's Tristram Shandy, 1759–67, and the narrator of Lord Byron's versified Don Juan, 1819-24), or for purposes which are both serious and comic (Thomas Carlyle's Sartor Resartus, 1833–34). See Robert Alter, Partial Magic: The Novel as a Self-Conscious Genre (1975), and refer to romantic irony.

|

|

One variety of self-conscious narrative exploited in recent prose fiction is called the self-reflexive novel, or the involuted novel, which incorporates into its narration reference to the process of composing the fictional story itself. An early modern version, Andre Gide's The Counterfeiters (1926), is also one of the most intricate. As Harry Levin summarized its self-involution: it is "the diary of a novelist who is writing a novel [to be called The Counterfeiters] about a novelist who is keeping a diary about the novel he is writing"; the nest of Chinese boxes was further multiplied by Gide's publication, also in 1926, of his own Journal of The Counterfeiters, kept while he was composing the novel. Vladimir Nabokov is an ingenious exploiter of involuted fiction; for example, in Pale Fire (1962). See metafiction in the entry novel.

We ordinarily accept what a narrator tells us as authoritative. The fallible or unreliable narrator, on the other hand, is one whose perception, interpretation, and evaluation of the matters he or she narrates do not coincide with the opinions and norms implied by the author, which the author expects the alert reader to share. (See the commentary on reliable and unreliable narrators in Wayne Booth, The Rhetoric of Fiction, 1961.) Henry James made repeated use of the narrator whose excessive innocence, or oversophistication, or moral obtuseness, makes him a flawed and distorting "center of consciousness" in the work; the result is an elaborate structure of ironies. (See irony.) Examples of James' use of a fallible narrator are his short stories "The Aspern Papers" and "The Liar." The Sacred Fount and The Turn of the Screw are works by James in which, according to some critics, the clues for correcting the views of the fallible narrator are inadequate, so that what we are meant to take as factual within the story, and the evaluations intended by the author, remain problematic. See, for example, the remarkably diverse critical interpretations collected in A Casebook on Henry fames' "The Turn of the Screw," ed. Gerald Willen (1960), and in The Turn of the Screw, ed. Robert Kimbrough (1966). The critic Tzvetan Todorov, on the other hand, has classified The Turn of the Screw as an instance of fantastic literature, which he defines as deliberately designed by the author to leave the reader in a state of uncertainty whether the events are to be explained by reference to natural causes (as hallucinations caused by the protagonist's repressed sexuality) or to supernatural causes. See Todorov's The Fantastic: A Structural Approach to a Literary Genre (trans. Richard Howard, 1973); also Erie S. Rabkin, The Fantastic in Literature (1976).

Drastic experimentation in recent prose fiction has complicated in many ways traditional renderings of point of view, not only in second-person, but also in first- and third-person narratives; see fiction and persona, tone, and voice. On point of view, in addition to the writings mentioned above, refer to Norman Friedman, "Point of View in Fiction," PMLA 70 (1955); Leon Edel, The Modern Psychological Novel (rev., 1964), chapters 3-4; Wayne C. Booth, The Rhetoric of Fiction (1961); Franz Stanzel, A Theory of Narrative (1979, trans. 1984); Susan Lamer, The Narrative Act: Point of View in Fiction (1981); Wallace Martin, Recent Theories of Narrative (1986).

|

|

1. Whether I shall turn out to be the hero of my own life, or whether that station will be held by anybody else, these pages must show. To begin my life with the beginning of my life, I record that I was born (as I have been informed and believe) on a Friday, at twelve o'clock at night. It was remarked that the clock began to strike, and I began to cry, simultaneously.

From “David Copperfielf” by Ch.Dickens

"...She jumped up from her chair and ran over to the piano.

"What a pity someone does not play!" she cried. "What a pity somebody does not play."

For the first time in her life Bertha Young desired her husband. Oh, she'd loved him – she'd been in love with him, of course, in every other way, but just not in that way. And equally, of course, she'd understood that he was different. They'd discussed it so often. It had worried her dreadfully at first to find that she was so cold, but after a time it had not seemed to matter. They were so frank with each other – such good pals. That was the best of being modern.

But now – ardently! Ardently! The word ached in her ardent body! Was this what that feeling of bliss had been leading up to? But then, then – "My dear," said Mrs. Norman Knight, "you know our shame. We are the victims of time and train. We live in Hampstead. It's been so nice."

"I'll come with you into the hall," said Bertha. "I loved having you. But you must not miss the last train. That's so awful, isn't it?"

"Have a whisky, Knight, before you go?" called Harry.

"No, thanks, old chap."

From “Bliss” by K.Mansfield

I lived at West Egg, the—well, the less fashionable of the two, though this is a most superficial tag to express the bizarre and not a little sinister contrast between them. My house was at the very tip of the egg, only fifty yards from the Sound, and squeezed between two huge places that rented for twelve or fifteen thousand a season. The one on my right was a colossal affair by any standard – it was a factual imitation of some Hotel de Ville in Normandy, with a tower on one side, spanking new under a thin beard of raw ivy, and a marble swimming pool and more than forty acres of lawn and garden. It was Gatsby's mansion. Or rather, as I didn't know Mr. Gatsby it was a mansion inhabited by a gentleman of that name. My own house was an eye-sore, but it was a small eye-sore, and it had been overlooked, so I had a view of the water, a partial view of my neighbor's lawn, and the consoling proximity of millionaires-all for eighty dollars a month.

From “Great Gatsby” by F.S.Fitzgerald

It was very late and everyone had left the cafe except an old man who sat in the shadow the leaves of the tree made against the electric light. In the day time the street was dusty, but at night the dew settled the dust and the old man liked to sit late because he was deaf and now at night it was quiet and he felt the difference. The two waiters inside the cafe knew that the old man was a little drunk, and while he was a good client they knew that if he became too drunk he would leave without paying, so they kept watch on him.

"Last week he tried to commit suicide," one waiter said. "Why?"

"He was in despair." "What about?" "Nothing."

"How do you know it was nothing?" "He has plenty of money."

They sat together at a table that was close against the wall near the door of the cafe and looked at the terrace where the tables were all empty except where the old man sat in the shadow of the leaves of the tree that moved slightly in the wind. A girl and a soldier went by in the street. The street light shone on the brass number on his collar. The girl wore no head covering and hurried beside him.

From “A Clean, Well-Lighted Place” by E.Hemingway

REFERENCES

1. Пелевина, Н.Ф. Стилистический анализ художественного текста [Текст] / Н.Ф. Пелевина. – Л.: Просвещение, 1980. – С. 194–204.

2. Арнольд, И.В. Стилистика. Современный английский язык: учеб. для вузов [Текст] / И.В. Арнольд. – 6-е изд. – М.: Флинта: Наука, 2004. – С. 210–214.

3. The Bedford Introduction to Literature. Reading. Thinking Writing / Michael Meyer. – Boston. New York. – 2002.

|

|

|

Наброски и зарисовки растений, плодов, цветов: Освоить конструктивное построение структуры дерева через зарисовки отдельных деревьев, группы деревьев...

Археология об основании Рима: Новые раскопки проясняют и такой острый дискуссионный вопрос, как дата самого возникновения Рима...

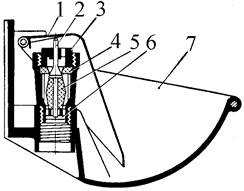

Индивидуальные и групповые автопоилки: для животных. Схемы и конструкции...

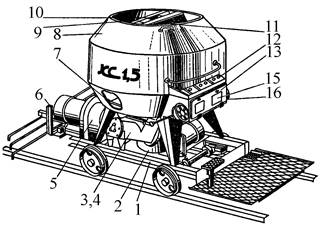

Кормораздатчик мобильный электрифицированный: схема и процесс работы устройства...

© cyberpedia.su 2017-2024 - Не является автором материалов. Исключительное право сохранено за автором текста.

Если вы не хотите, чтобы данный материал был у нас на сайте, перейдите по ссылке: Нарушение авторских прав. Мы поможем в написании вашей работы!