EACH VOTER'S RANKING OF OUTCOMES A, B and С.

| VOTER

| A

| В

| С

|

| 1

| 1

| 2

| 3

|

| 2

| 3

| 1

| 2

|

| 3

| 2

| 3

| 1

|

Median voter

·

• • • • ••• • • •• • • • • •••• •

£0 £250 £500 £750 £1000

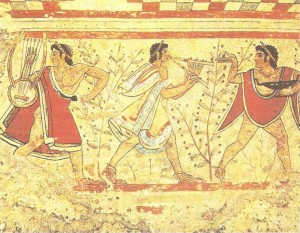

Figure 3-1. THE MEDIAN VOTER. Each dot represents the preferred expenditure of each of 17 voters. The outcome under majority voting will be the level preferred by the median voter. Everybody to the left will prefer the median voter's position to any higher spending level. Everybody to the right will prefer it to any lower spending level. The median voter's position is the only position that cannot be outvoted against some alternative. Hence it will be chosen.

The Median Voter. Majority voting does not always lead to inconsistent public choice. Figure 3-1 shows for 17 voters how much between £0 and £1000 each would like to spend on the police. Each dot represents an individual voter's preferred amount.

We also assume that each voter will vote for a spending level close to his or her own preferred amount rather than for one that is further away. A voter who wants to spend £250 will prefer £300 to £400 and will prefer £200 to £100. Each person has single-peaked preferences, being happier with an outcome the closer it is to the peak or preferred level as judged by that individual.

Now suppose there is a vote on how much to spend on the police. A proposal to spend £0 would be defeated by 16 votes to 1. Only the voter represented by the left-hand dot in Figure 3-1 would vote for £0 rather than £100. As we move to the right we get more people voting for any particular proposal. Figure 3-1 emphasizes the special position of the median voter. With 17 voters, the median voter is the person who wants to spend the ninth-highest amount on the police. There are 8 voters wanting to spend more and 8 wanting to spend less. The median voter is the person in the middle on this particular issue.

What is special about the median voter? Suppose the vote is between the amount the median voter wants to spend and some higher amount. The 8 people wanting less than either will vote for the median voter's proposal, and so will the median voter. There will be a majority against higher expenditure. Bу an identical argument there will be a 9-8 majority against lower expenditure when the alternative is the amount wanted by the median voter. Hence the median voter's preferred outcome will be the one that is chosen by majority voting.

Thus, majority voting works when each individual has single-peaked preferences. The paradox of voting arises in Table 3-4 precisely because preferences are not single-peaked. Suppose outcome A is low expenditure, В is moderate expenditure, and С is high expenditure on the police. Voter 1 prefers low to moderate and moderate to high. Voter 1 has single-peaked preferences. So does voter 2, whose peak is at moderate expenditure. But voter 3 prefers high to low and low to moderate expenditure, even though moderate expenditure is closer than low expenditure to the best outcome of high expenditure. Voter 3 does not have single-peaked preferences.

This is why majority voting is likely to get into trouble when individual preferences are not single-peaked. In contrast, with single-peaked preferences the outcome is likely to be that most preferred by the median voter. Consistent public choice under majority voting on particular issues is more likely the more each voter feels that the next best thing is an outcome close to that voter's preferred outcome. On issues where voters feel they must make an all-or-nothing choice between very different alternatives, intermediate positions are a complete waste of time. The failure of preferences to be single-peaked may result in inconsistent public choices.

Legislators

When preferences are single-peaked the median voter models helps us to understand how society makes decisions on particular issues, especially if there is a referendum on the issue. But the process of making decisions through legislative compromises is much more complicated. Decisions are not made issue by issue. There may be a trading of votes between different issues so that an individual gets a package that is preferred. Logrolling is one example.

Table 3-5 shows two issues, A and B, and three legislators, 1, 2, and 3. The value in pounds of each outcome to each individual is shown. These values are merely illustrative measures of how much each individual stands to gain or lose under each outcome. Suppose each person votes for a proposal only if the outcome is positive. Person 1 votes against A and B, person 2 against A but for B, and person 3 for A but against B. Both issues would be defeated on a majority vote.

Table 3 –5. Logrolling

| PERSON

| A

| B

|

| 1

| - 4

| - 1

|

| 2

| - 3

| 4

|

| 3

| 6

| - 1

|

Now suppose persons 2 and 3 do a deal and vote together. Suppose they decide to vote for A, which person 3 wants, and for B, which person 2 wants. Person 2 will make a net gain of £1, gaining £4 since В passes, and losing only £3 when A passes. Person 3 gains a total of £5, gaining £6 since A passes and only losing £1 when В passes. By forming a coalition they do better than they would have done under independent majority voting, when neither A nor В would have passed.

This kind of model helps us understand some behaviour by politicians, but they are subject to many other forces. They want to do good, to be powerful, to be popular, and above all to be re-elected. Even if society as a whole has consistent goals, it does not follow that politicians will act so as to reflect those goals as faithfully as possible.

Civil Servants

Civil servants influence public decision-making and its execution in two ways. They offer advice and expertise, which influence the government in deciding how laws and policies should be framed. They are also responsible for carrying out the enacted laws and stated policies and may have some discretion in how far and how fast to put into practice the directives with which they have been issued.

Civil servants also have vested interests. Those at the defence ministry are likely to try to persuade the government to expand defence activities. Those in education will press for higher spending on education. Although the final responsibility must be taken by elected politicians, governments sometimes argue that civil servants are quite skilled in obstructing policies that the civil servants do not like.

The main point of this section is that the process through which governments make spending and taxing decisions does not magically and automatically translate society's wishes into the appropriate action. Indeed, as the paradox of voting shows, it may be impossible for society always to express consistent aims. The simple view that the government acts to maximize the public good is a convenient one on which we frequently fall back. But a complete understanding of how public choices are made, and could possibly be made, requires an extension of the ideas we have briefly examined in this section.

Summary

- Governments play a major role in modern mixed economies. The scale of their activities is between a third and two-thirds of national income.

- The role of government extends beyond purchasing goods and services, raising taxes, and making transfer payments. Governments also set the legal framework, regulate economic activity, and attempt to stabilize the business cycle.

- Taxes affect the allocation of resources. Taxing a good raises the price to the buyers and lowers the price to the seller, thereby reducing the output of the good.

- Government intervention in the economy can be justified on economic grounds by market failure. Stabilizing the business cycle, deciding on the amount of public goods, responding to externalities, correcting informational problems, preventing the exercise of market power, and creating a socially desirable distribution of income and merit goods are all economic grounds for a government role in the economy.

- Government decisions should represent the interests of society, but society's true preferences may be hard to ascertain. A democratic society votes for legislators who make decisions that are carried out by civil servants under the supervision of the government.

- Unless individual preferences are single-peaked, majority voting can lead to inconsistent public choices. With single-peaked preferences, majority voting will lead to consistent results. Society will tend to choose according to the median voter on any issue. Legislative decisions may reflect complex deals and vote-trading on different issues. There is no simple relation between the final choices of public servants and the underlying preferences of the voters who make up society.

Exercise 1. Define the following terms in English:

Public choice Paradox of voting Single-peaked preferences

Median voter Logrolling

Exercise 2. Answer the following questions:

1. An individual usually manages to make consistent choices. Why is it harder for governments?

2. Common Fallacies. Show why the following statements are incorrect: (a) My tax bill is £100: that is how much worse off the tax has made me. (b) Public goods are whatever the public sector provides. (c) Free markets always allocate resources efficiently. (d) Majority voting makes public decisions reflect society's wishes.

Part V. Taxes

“But in this world nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes.” – Benjamin Franklin, 1789.

Few economic topics excite controversy more easily than taxes. Wile most would agree that neither government nor modern society could survive without them, taxes are more likely to be criticized than praised.

Why Do Governments Collect Taxes? Although the principal purpose of taxes is to pay for the cost of government, it is not the only function taxes serve.

Ø Sometimes taxes are levied to protect selected industries. For a number of years a tariff (a tax on imports) helped to protect American steel manufacturers by making imported steel more costly than it would have been otherwise.

Ø Taxes have also been used to discourage activities the government believes to be harmful. For example, taxes on cigarettes and liquor, so called “sin taxes”, have been levied both to raise money and to discourage people from smoking and drinking.

Ø Taxes have been used to encourage certain activities. In the 1980’s, for example, the government wanted to encourage business to modernize plants and increase productivity. It did so, in part, by offering to reduce taxes of firms that purchased new machinery and equipment.

Ø The federal government can use its ability to tax to regulate the level of economic activity. The size of the economy is directly related to consumer and business spending. By increasing or decreasing taxes, government can directly affect the amount of money available to be spent.

Evaluating taxes. Most people would agree that some taxation is necessary, but the question of which taxes and in what amounts can lead to considerable disagreement. In comparing the merits of one tax to another, it is convenient to focus on the following questions:

Who ought to pay taxes?

What types of taxes are being considered?

Who will actually pay the taxes?

Who Ought to Pay Taxes?

The benefits-received principle of taxation states that those who benefit from a government program are the ones who ought to pay for it. Consider, for example, the case of a highway tunnel or bridge. In keeping with the benefits-received principle, motorists using these should have to pay for a toll.

Benefits-received works just fine when it comes to things like bridge and tunnel tolls or admission to a public beach, but it has its limitations. For example, is it fair to ask low-income families or the disabled to bear the cost of the programs designed to help them?

The ability-to-pay principle states that taxes ought to be paid by those who can best afford them, regardless of the benefits they receive. In arguing in favor of the ability-to-pay principle, economists often cite Engel’s Law. It states that as income increases, the proportion spent on luxuries increases, while that spent on necessities decreases. It follows that taxing higher-income groups may deny them certain luxuries, but taxing the poor reduces their ability to buy necessities.

Also, some benefits are indirect. If Mr. and Mrs. Jones have children in the public school, they can see the direct benefit of their school taxes. But Mr. and Mrs. Smith may feel they get no benefit from the school because they have no children.

We all benefit from having an educated workforce, however. Thanks to education, the nation’s productivity is higher, and we can all share in the additional output that results from it. If the Smiths own a business, they benefit from having workers who have been trained to read, write and solve mathematical problems.