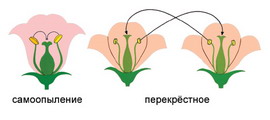

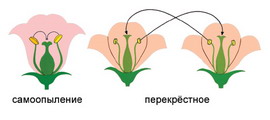

Семя – орган полового размножения и расселения растений: наружи у семян имеется плотный покров – кожура...

Своеобразие русской архитектуры: Основной материал – дерево – быстрота постройки, но недолговечность и необходимость деления...

Семя – орган полового размножения и расселения растений: наружи у семян имеется плотный покров – кожура...

Своеобразие русской архитектуры: Основной материал – дерево – быстрота постройки, но недолговечность и необходимость деления...

Топ:

Определение места расположения распределительного центра: Фирма реализует продукцию на рынках сбыта и имеет постоянных поставщиков в разных регионах. Увеличение объема продаж...

Установка замедленного коксования: Чем выше температура и ниже давление, тем место разрыва углеродной цепи всё больше смещается к её концу и значительно возрастает...

Марксистская теория происхождения государства: По мнению Маркса и Энгельса, в основе развития общества, происходящих в нем изменений лежит...

Интересное:

Инженерная защита территорий, зданий и сооружений от опасных геологических процессов: Изучение оползневых явлений, оценка устойчивости склонов и проектирование противооползневых сооружений — актуальнейшие задачи, стоящие перед отечественными...

Аура как энергетическое поле: многослойную ауру человека можно представить себе подобным...

Национальное богатство страны и его составляющие: для оценки элементов национального богатства используются...

Дисциплины:

|

из

5.00

|

Заказать работу |

|

|

|

|

And to your desktop soon?

Sheridan Johns

USA

Who was Rochlin? What was the nature of his collection? When and how did his collection move from South Africa to Quebec? What are the prospects that this collection will be available on your desktop computer soon? I will address these questions in this paper, interweaving my answers with an account of my double encounter with this archive, first in 1963 and again, forty years later, in 2003.

Samuel Abraham Rochlin was one of South Africa's first young communists. Rochlin, son of 'Litvak' Jewish immigrants and fluent in Yiddish, was born in 1904 in Cape Town where he attended school. Physically handicapped (he was a hunchback), he was an avid reader and eager student, with strong roots in the culture of the Jewish immigrant community and its politics. Undoubtedly, like the majority of the immigrant community in which he lived, he eagerly followed the Bolshevik revolution and its impact upon the homeland of his parents. He was drawn to the lively, but small, circles of socialists who actively debated how socialism could be advanced, not only in distant Europe, but also in South Africa, Already in January, 1921, there was a Young Socialist League in Cape Town which by May, 1921, had converted itself into a Young Communist League. Rochlin was secretary of the group. In this capacity he sent a letter of solidarity to the Young Communist International (YCI) in Moscow. The letter was published in the journal of the YCI in mid-1921.[101]

In July, 1921, various small socialist groups that had identified with the Bolshevik revolution came together to form the Communist Party of South Africa (CPSA). There is no record that Rochlin became a member of the CPSA, nor did he apparently publish again in the communist press in South Africa or elsewhere. Instead, he turned his focus to Jewish affairs and South African history, voraciously reading 19* century and early 20th century South African journals and newspapers from which he drew information for numerous articles published in Jewish and Africana journals until the time of his death in 1961. The headline of his obituary in the Rand Daily Mail read, "Jewish History Expert Dies".[102]

Sometime in the 1920s he moved from Cape Town to Johannesburg where he lived for the remainder of his life. In 1929 he was a contributor to the first South African Jewish Year Book issued under the joint auspices of the South African Jewish Historical Society and the South African Jewish Board of Deputies.3 In the mid-1930s he was working with The Zionist Record. At the time of his- death he was the chief research worker of the South African Jewish Historical Society and the archivist of the South African Jewish Board of Deputies.[103]

His obituary in Africana Notes and News characterized his unique intellectual trajectory: "because he was incapacitated and could not take part in robust sports, [he] spent his free time from boyhood until death in reading old South African newspapers and journals in libraries and in systematically recording items of interest. He was catholic in his tastes, and his interests ranged from abstruse subjects connected with Islam, through Russian publications on South Africa to rock engravings and Cape printing. In after years he came to Johannesburg, and continued his interest in searching out obscure information. He copied the relevant passages in longhand and noted his sources with meticulous care....he had a prodigious memory and knew whether he had information on a specific topic even if he had not thought of it for a decade."[104]

|

|

To his friends in the 1930s he was known as "Roch". A contemporary from The Zionist Record characterized him as "a gay little man, fond of practical jokes, and ineffably kind to all and sundry. His mental integrity earned him great respect. It seemed that there was nothing he did not know. He had an amazing, encyclopeadic brain, and there was a constant sense of surprise in being with him."[105]

Rochlin never married and lived reclusively in a one-roomed apartment. He was an avid bibliophile. In the words of Baruch Hirson, a South African scholar and Trotskyist who knew Rochlin in the 1940s and 1950s, "the walls of [his apartment] were concealed by columns of books, two or three layers thick, lying sideways from floor to a height of several feet. He also had a cupboard filled with journals, cuttings, pamphlets, and ephemera."[106]

Rochlin died without heirs. After his death the collection, including journals, cuttings, pamphlets, and ephemera, was taken into the house of a well-established Jewish professional, active in Zionist groups and affiliated with the South African Jewish Board of Deputies.

In 1962-63 I had a Foreign Area Fellowship from the Ford Foundation to South Africa to conduct dissertation research on the history of the CPSA. Officially, under the terms of my student visa to South Africa, I was engaged in research on 'the political role of labor in the 1920s and 1930s'. Despite the increasingly tense post-Sharpeville political environment I was able to locate ample documentation on the CPSA and left/radical politics from World War I through the 1940s in university and public libraries. Many of the most interesting documents were not listed in the catalog and stored off the regular shelves, but they were still accessible to researchers like myself. I had also had some luck in locating private collections squirreled away both in libraries and in private homes.

The Rochlin collection was the most unexpected find of my stay in South Africa. I am not sure today how I was put in contact with the person in whose home the Rochlin collection was stored. Very probably it was Fanny Klenerman, the legendary proprietor of Vanguard Books, Johannesburg's most well-stocked independent bookstore. She was an ex-communist (exiting the party in the late 1920s) and former Trotskyist who had undoubtedly known Rochlin since the 1920s when they were both active in communist groups. I also no longer remember the name of the man who had custody of the Rochlin collection, but I do know that he was not actively engaged with radical anti-apartheid politics. He welcomed me into his home, took me upstairs to the sun-porch where Rochlin's boxes and files were stored, offered me a desk where I could take notes with my portable typewriter, and left me to 'dig' on my own.

For the better part of a week I was transfixed by what I found rummaging through the haphazardly piled boxes and files of cuttings, journals, and newspapers that had been removed from Rochlin's apartment. The bulk of the fascinating materials that I perused did not concern South African socialist and Marxist groups, but my winnowing of the collection for materials about the early history of communism was not in vain. I found runs, albeit often incomplete, of obscure communist and Trotskyist journals as well as many pamphlets of anti-fascist, trade union, communist, and Trotskyist organizations from the 1920s through the 1940s. Even more valuable (and unexpected) were unique unpublished materials: a handwritten journal of a Communist Propaganda Group, a breakaway body of eight members that existed in Cape Town immediately prior to the formation of the CPSA in July, 1921, a collection of correspondence of Cecil Frank Glass, a prominent communist in the early 1920s and candidate in 1924 for municipal office in Johannesburg, and typescript copies of the proceedings of early CPSA national congresses. Pounding away on my portable typewriter, I hurriedly took notes from the unpublished materials as well as from the published materials that I had not located elsewhere. They were added to my growing collection of typewritten notes that were then shipped in small packages out of South Africa for future use when I would write my dissertation.

|

|

In subsequent years, long after the completion of my dissertation, I wondered about the fate of the Rochlin collection. Given the sensitivity of its contents and its resting place in a private home of an individual who had no strong political reasons to preserve ephemera of early South African communist history, particularly in a climate where possession of publications of 'banned organizations' was a punishable crime, I presumed that the collection had either been destroyed, or at best, had gotten lost and forgotten. Thus, it was a surprise and relief when in the late 1980s, I was informed by Baruch Hirson, then in exile in London, that he had learned that the Rochlin collection was in a university library in Montreal, Quebec. Having long since used the notes that I had taken from the collection two decades earlier, and at the time not engaged with projects focused upon the period of the 1920s and 1930s, I had no immediately urgent reason to travel to Montreal to consult the Rochlin collection once again. My days of excited discovery on the sun-porch of the house in the northern suburbs of Johannesburg remained a sharp, but distant, memory.

Out of the blue in mid-2003 came an email from Judy Appleby, the special collections librarian at Concordia University in Montreal, asking whether I would advise her and her colleagues about the importance and value of the documents in the Rochlin collection. Not only did they want to ensure the preservation of the collection, they were eager to facilitate access to their unique collection by scholars everywhere. To this end they had devised an innovative project to scan the full collection in order to put it 'on line' in its entirety and thus accessible to scholars in South Africa and around the world. They invited me, as a scholar who had published a major work on the early history of South African communism, to assess the potential value of the collection for historians of radical politics in 20th century South Africa. I accepted and thus, in November, 2003, forty years after I had first seen the collection in Johannesburg, I was 'reunited' with the Rochlin collection in Quebec.

I was curious to learn how the Rochlin collection had ended up in this university in Canada, a university whose programs neither specialized in African studies, nor in the history of communism and socialism. I was informed that Donald Savage, a historian on the faculty of Loyola College, one of two higher education institutions that had merged in 1974 to form Concordia University, had bought the collection in South Africa in 1965 for CN$504.79. Savage was a specialist on east African colonial history and was one of the early Canadian academics who had research interests in Africa. In a recent email message to me Savage reported, "at the time the then Rector of Loyola College, the late Very Rev. Patrick Malone S.J., was persuaded by myself and others to make African studies a major commitment of the College. This involved creating courses in history, political science, etc., financing scholarships for African students, and a major buying operation for the Library. This was extraordinary for a small and not very well financed college. I was authorized to buy extensively for the Library especially through booksellers in South Africa and the United Kingdom. Alas, I cannot remember which particular bookseller sold Loyola the Rochlin collection. It was an accident of history that Loyola happened to be buying at that time and could respond to offers almost instantly. When Loyola merged with Sir George Williams to become Concordia University, the interest continued but the priority did not. As a consequence the new university did not take much interest in the Rochlin papers until Judy Appleby took charge."[107]

|

|

It was these unique circumstances that brought the Rochlin collection out of South Africa into Quebec. It was saved both from possible destruction in South Africa as its contents were primarily publications of 'banned' organizations and from continuing oblivion as part of the much larger Rochlin hoard of clippings, journals, and newspapers. It was brought into a secure academic repository where it was available to researchers, albeit far from South Africa and in an institution well off the research map of most Africanists. Now, after many years of neglect, librarians at Concordia University are again taking interest in the Rochlin collection.

My 'reunion' in Montreal with the Rochlin collection was suspenseful, albeit differently than my first encounter with it in Johannesburg. My first concern was whether the original documents that I had seen in Johannesburg were in still in the collection. To my great disappointment, I did not find the handwritten journal of the Communist Propaganda Group, the most unique of the documents that I had seen in Johannesburg. But I did find the correspondence of Glass, a prominent communist in the early 1920s and candidate in 1924 for municipal office in Johannesburg, and the typescript copies of the proceedings of early CPSA national congresses, very probably also once belonging to Glass. In addition to the Glass papers, I found the eclectic collection of obscure communist and Trotskyist journals as well as many pamphlets of anti-fascist, trade union, communist, and Trotskyist organizations from the 1920s through the 1940s that I remembered reading in Johannesburg. Many of these items very possibly had also belonged to Glass (and Klenerman, who had been active with Glass in the CPSA and the Trotskyist movement).[108]

How had these items come into the possession of Rochlin? Through a letter from Baruch Hirson to the Concordia librarians I learned that Klenerman, the first wife of Glass, had given her ex-husband's papers to Rochlin for safekeeping. Hirson reported that Klenerman "said that when others were burning papers (presumably in 1939 when it seemed possible that a right wing pro-German government would be formed) she decided to ask Rochlin to place these papers at the Jewish Board of Deputies (secretly) so that they might be saved."8 More recently, through reading transcripts of tapes of recollections by Klenerman, I have confirmation of Hirson's account. In Klenerman's words, "among those records were some left by Frank Glass, who had also collected political documents and these I decided I could not possibly burn or destroy. So I approached a young man, who worked for the S.A. Jewish Board of Deputies, as their archivist. He was a very scholarly person, certainly not conservative as was the rest of the Board, but perceptive and open-minded, and intelligent.

|

|

He was crippled, unfortunately. He had read very widely. And when I brought him Frank's records which go back very many years, dealing with the early struggles of the working class....he was overjoyed to accept them; and he said he would keep them in the archives and make use of them. No one would find them there. It was quite safe"[109]

If Rochlin had not taken the papers in 1939 it is quite possible that they would have been destroyed or confiscated by the South African security police. Thus, Rochlin saved them by keeping them. In 1964 or 1965 clearly someone in South Africa knowledgeable about the value of the socialist and communist materials in Rochlin's possession had selected out these items from the larger collection for sale to a buyer interested in Africana who could provide a safe academic haven. When Savage in 1965 bought the Rochlin collection out of South Africa into Quebec the Glass papers were saved anew from possible destruction.

Documents in the Rochlin collection are unique. The letters and other personal papers of Glass are originals and do not exist elsewhere. - To my knowledge the official typewritten copies of the minutes of meetings of the Communist Party of South Africa do not exist in any party archive in South Africa, nor in any other library in South Africa. (They are available in the Russian State Archives in Moscow, but it is not easy for outside researchers to gain access to them). A number of the items of the Young Communist League of South Africa are also undoubtedly not available elsewhere, although individual items might be found scattered in files in the Russian State Archives. Similarly, the ephemera pertaining to campaigns by communists for various offices are also surely rare, if not unique, to the collection. Other items in the Rochlin collection, while not unique, are also certainly scarce, particularly copies of newspapers such as The Black Man and The African World. Similarly the cyclostyled publications of the Labour League of Youth of South Africa (Youth) and of the Johannesburg District of the Communist Party (Nkululeko) are also rare, as well as the ephemeral publications of the several Trotskyist groups.

In short, the Rochlin collection contains both unique items not found anywhere else and items that are extremely rare and difficult to locate. Furthermore there are items, including copies of newspapers, for which the holdings in some cases are incomplete in South African libraries. Other documents, including newspapers held in the National Library of South Africa, are useful p_er se for researchers, particularly those who may not be able immediately to visit the National Library. On these grounds alone it is extremely fortunate that the Rochlin collection has been preserved intact at Concordia University. It would be even more fortunate if the collection could be made accessible easily.

The librarians at Concordia University have carefully inventoried the Rochlin collection, determining that there are 5595 pages of documents. In addition to the Glass papers, the minutes of the CPSA congresses, and the runs of South African newspapers and journals, there are also ninety-two pamphlets relating to socialism, anti-fascism, labor and trade union movements, and communism in South Africa. As the Concordia librarians note, "most of the documents in the Rochlin Collection are in brittle condition, some in a very fragile state. New technologies will allow the preservation of the contents and appearance of these documents as well as to make them available to researchers around the world. A detailed record of each item in the Collection will allow researchers to find relevant sources and link to images of the documents themselves."[110]

The librarians at Concordia University are continuing to create a database with a record for each item in the collection. As further funding becomes available the librarians plan to take full advantage of new technologies to make the contents of the Rochlin collection available 'on line'. Even if it were possible initially to scan and make accessible only the most unique and fragile items an important step would have been taken. It would be even more noteworthy - indeed, invaluable - for researchers if each and every page of the documents in the collection could be scanned and put on line to complement the database. It would serve the interests of researchers into South African political and labor history who would be able to access rare and important material without leaving their 'home' libraries. By putting the Rochlin collection of South African documents 'on line', Concordia University will serve as a pioneer in creative use of new information technology. Anyone with access to the internet will be able to bring the Rochlin collection to their desktop computer. Researchers could obtain the documents they need, perhaps only a few unique items, without having to travel to Montreal from South Africa, Europe, or elsewhere in North America.

The project of putting the complete Rochlin collection on line is a path-breaking model for making accessible small, but valuable, archives located far from the countries to which they are most relevant and in which they would be most often consulted. Like many other small archives, containing diverse ephemera and incomplete files of newspapers and journals, the Rochlin collection contains documents of differing utility for different researchers. If analogous collections elsewhere could similarly be put 'on line', rare and previously infrequently utilized archival resources in many libraries and private collections would then be available around the world without the necessity of traveling half way around the world. In this fashion the technology of the 21st century will serve to make archives of the 20th century (and earlier) an even more accessible key to African history.

|

|

|

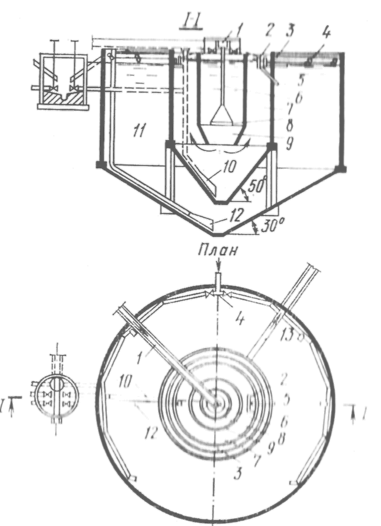

Типы сооружений для обработки осадков: Септиками называются сооружения, в которых одновременно происходят осветление сточной жидкости...

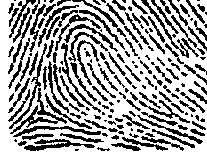

Папиллярные узоры пальцев рук - маркер спортивных способностей: дерматоглифические признаки формируются на 3-5 месяце беременности, не изменяются в течение жизни...

Типы оградительных сооружений в морском порту: По расположению оградительных сооружений в плане различают волноломы, обе оконечности...

Механическое удерживание земляных масс: Механическое удерживание земляных масс на склоне обеспечивают контрфорсными сооружениями различных конструкций...

© cyberpedia.su 2017-2024 - Не является автором материалов. Исключительное право сохранено за автором текста.

Если вы не хотите, чтобы данный материал был у нас на сайте, перейдите по ссылке: Нарушение авторских прав. Мы поможем в написании вашей работы!