Археология об основании Рима: Новые раскопки проясняют и такой острый дискуссионный вопрос, как дата самого возникновения Рима...

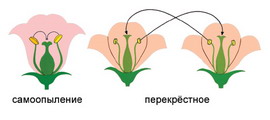

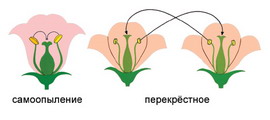

Семя – орган полового размножения и расселения растений: наружи у семян имеется плотный покров – кожура...

Археология об основании Рима: Новые раскопки проясняют и такой острый дискуссионный вопрос, как дата самого возникновения Рима...

Семя – орган полового размножения и расселения растений: наружи у семян имеется плотный покров – кожура...

Топ:

Оценка эффективности инструментов коммуникационной политики: Внешние коммуникации - обмен информацией между организацией и её внешней средой...

Методика измерений сопротивления растеканию тока анодного заземления: Анодный заземлитель (анод) – проводник, погруженный в электролитическую среду (грунт, раствор электролита) и подключенный к положительному...

Организация стока поверхностных вод: Наибольшее количество влаги на земном шаре испаряется с поверхности морей и океанов...

Интересное:

Распространение рака на другие отдаленные от желудка органы: Характерных симптомов рака желудка не существует. Выраженные симптомы появляются, когда опухоль...

Средства для ингаляционного наркоза: Наркоз наступает в результате вдыхания (ингаляции) средств, которое осуществляют или с помощью маски...

Уполаживание и террасирование склонов: Если глубина оврага более 5 м необходимо устройство берм. Варианты использования оврагов для градостроительных целей...

Дисциплины:

|

из

5.00

|

Заказать работу |

|

|

|

|

Comments

In this video some of our University of Leicester PhD students discuss the research methods they have used, and why.

Play Video

Close transcript

Download video: standard or HD

0:07 Skip to 0 minutes and 7 seconds My data collection method is probably-- it's all about the centre of my whole PhD projects. I think to some PhDs, the data-collection method just a means to an end, whereas for mine, it's part of the identity of the project, and it's part of my contribution, really. So in my proposal, the data-collection method came forward really strong, because that was part of what was new about what I was doing and how I was researching this area. And I used something called screen-capture software, which in my participants, downloaded onto their laptops. And they recorded their laptop screens when they were on Facebook. So I had a live recording of their interactions online. So I do semi-structured interviews.

0:54 Skip to 0 minutes and 54 seconds I've done that from my masters dissertation and for my PhD. I've started looking discourse analysis, because I look at material put out by governments and think tanks, and policy institutions. These could be government documents. It could be treaties. It could be any sort of official documents, just to find out how countries that are responding to certain actions from other countries. I also interview people in think tanks and policy institutes in the academia journals. So that's something I do. I do discourse analysis, I do semi-structured interviews, and I'm also working on a response frame to understand, what are responses?

1:42 Skip to 1 minute and 42 seconds A set of questions that helps one understand how countries are responding and if that action is actually a response to previous action. Well, my study is a case study. The case study is the main research method for me. And in the case study, I also adopt a multi submethods to look into detailed stuff-- the material. I'll adopt qualitative data and quantitative data. So I use different methods. At the moment, I employ qualitative-research approach. So specifically, I use ethnographic observations, as well as in-depth interviews. I also use a bit of photographs as well. And nothing has changed with my methodology.

2:44 Skip to 2 minutes and 44 seconds But I think I actually got into the qualitative side of things, because I am not really one of the strongest reads. But mathematics, or my numerical ability is not very good. I've used probably predominantly conversation analysis, which is very macroanalysis with people's interactions and the language that they use. And actually, as I've gone on, and I've engaged with my data further into my study, I've realised that I might have to actually draw upon other analysis methods as well, and not just conversation analysis. As you go on, you realise that you need a set of different tools rather than just the one tool you thought you were going to need at the beginning.

|

|

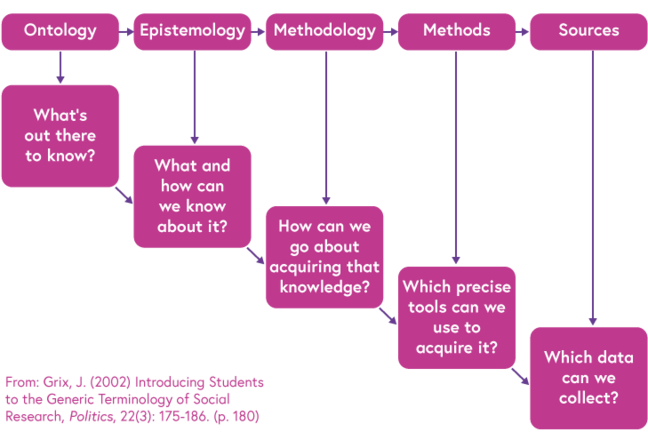

The interrelationship between the building blocks of research

Comment

‘Research design’ can be viewed as a plan to collect and analyse data systematically to address research questions. It includes a pin-pointing of the nature and types of the data to be collected, the methods to be used, how the data will be subsequently treated, and the procedures through which these will be analysed. The fundamental issue with research design is whether it genuinely delivers the empirical material that is appropriate to address the core research questions. A good research design offers a viable route for gathering appropriate material. By contrast, a poor research design exploits material that is either inconsistent and/or insufficiently relevant.

‘Methodology’ refers to the techniques of data collection and analysis. In the Social Sciences disciplines, one of the major distinctions in research methodology is between Quantitative and Qualitative methods. Quantitative methods gather numerical data that are treated through statistical analysis. Qualitative methods can collect either textual or visual data (or a combination of both) that are subject to systematic non-numerical analysis. These two sets of methods can thus involve very different considerations around research design. For example, quantitative methods tend to use large numbers of data points, but relatively ‘thin’ information at each point, whereas qualitative methods use smaller overall numbers of data points, but explore very ‘thick’ information at each point.

Both Research Methodology and Research Design are informed by meta-conceptual or philosophical considerations. Choosing to do, say, an experiment rather than an interview is not merely a technical question, but it also involves siding with one particular philosophical approach to the social world rather than another. These experiments tend to be associated with a ‘mechanistic’ world view, whereas interviews belong with a ‘holistic’ or ‘organismic’ world view. A project in Literary or Historical studies, for example, may also be underpinned by a conceptual or theoretical perspective, e.g. formalist, feminist or Marxist.

This week we will argue that a well-developed research design is essential to a successful research proposal. It should include brief reference to the thesis’ or researcher’s research philosophy, sketch out the overall design and technical details of data collection, and clearly articulate the methods to be used and the procedures that will be adopted for data analysis.

Broadly speaking, the interrelationship between the building blocks of research can be summarised as in the diagram at the top of this step.

Research philosophy

Comments

Although the title PhD is formally a ‘Doctorate in Philosophy’, we do not expect students to become trained philosophers! (though a few of you may do!) Moreover, we are aware that some students, particularly those in the arts and humanities, will not be expected to engage systematically or in detail with philosophical considerations.

We do, however, expect that students will become sufficiently familiar with fundamental conceptual issues in how knowledge is produced so that they are able to make sensible decisions regarding their own research design and methods. To this end, all students, whether Full-Time, Part-Time or Distance Learning students, are required to take research training at that start of their doctoral studies. For students in the social sciences this training includes sessions on research philosophy and on methods. The following paragraphs are therefore aimed specifically at students undertaking social sciences projects.

|

|

By ‘philosophy’, we usually mean the ‘Western’ or ‘Euro-American’ tradition. This philosophical tradition spans Ancient Greek philosophy (e.g. Heraclitus, Plato) through to the Critical Philosophy of the Enlightenment (e.g. Hume, Kant) and informs modern Analytic (e.g. Frege, Moore) and Continental philosophy (e.g. Heidegger, Deleuze). The Western tradition has been dominated by the tendency to make sharp bifurcations in its subject matter (sometimes known as ‘dualisms’). These include distinctions between the natural world and the human world (i.e. nature vs culture), the division of ‘mind’ from ‘body’ along with the parallel division of ‘individual’ from ‘society’, and the separation of religion from politics. Whilst these dualisms are hotly contested in Philosophy, they often re-appear, for example in broad Social Science debates (and some Arts and Humanities debates, including, for example, Archaeology) such as the one around ‘structure’ versus ‘agency’.

Activity

As a first task, find some basic definitions of (some of) the terms and traditions named above, such as Analytic and Continental philosophies and ‘agency’. Write these down in your Reflective Journal. En route, ask yourself how many of these might immediately sound or feel relevant to your own topic area? Then, using Google Scholar, look to find an article that might show this relevance.

Ontology

Comments

Probably the most important philosophical distinction of all is that between ontology and epistemology. Ontology refers to the fundamental ‘stuff’ that we take to be the basis of our world. Whilst theorising in most academic work is influenced by philosophical debates around ontology, it is not always necessary in a doctoral research proposal to explicitly align yourself with a specific philosophical school of thought. However, in considering a research design it is ‘good practice’ to consider where your own approach (and the research traditions you have engaged with) falls.

At one end, we can imagine a completely mechanistic view of the social world. Here, any event which occurs is an ‘effect’ which is produced by a clear ‘cause’. Think of a pinball machine (or flipper), where every movement of the ball can be calculated by measuring how it is struck by the flippers and the targets. From this perspective, anything that happens occurs as a consequence of how the parts function together. If we are able to measure how they work sufficiently well, then we can model and predict any given event.

At the other end, consider an entirely holistic or organismic world-view. Here, everything is in motion, with fluid relationships springing up and falling apart on a contingent basis. Imagine the flow of a river, each ripple and swirl on the surface of the moving water being the product of a complex interplay between current, wind and turbulence, which can change on a moment-by-moment basis. As we have to start with the idea of continuous change and of processes that interact together in non-deterministic ways, rather than try to predict single events, we have to take a broadly stochastic or probabilistic view of the kinds of events that might be possible given the processes involved.

Now, in practice, most research falls somewhere between these two absolute positions on ontology. But it is nevertheless helpful to ask yourself whether your own conceptualization of your object or field of study tends towards the machine-like or the process-like because this will have implications for how you frame your research problem and the way you choose to study it.

Epistemology

Comments

Epistemology is the philosophical term for how we come to know the world. For example, many Western philosophies have been built on the idea that, at a fundamental level, our knowledge of the world is limited by our human capacities – we can never truly know the world ‘as it actually is’. This is called idealism. The converse idea, that in principle the world is knowable in its entirety, and that through advances in science and technology we will know ‘more’ and ‘better’, is termed realism. In social science, idealism and realism are usually exchanged for the terms constructionism (or interpretivism) and positivism. Both of these terms are fairly abstract and often are broadly misunderstood, but, as with ontology, it is helpful to imagine them as marking out the extreme ends of a continuum of positions.

|

|

The positivist world-view is dominated by the idea that it is possible to produce new knowledge by making a series of systematic observations of any given phenomenon. For example, understanding why a financial crash happens might be done by collecting data on stock movements and investor confidence levels over the years preceding and succeeding the crash. These raw data are treated as a set of ‘facts’ that can serve as the basis for modelling and theorizing. Developing better techniques for making observations, such as producing new ways to measure investor confidence, leads to advances in knowledge. Conversely, if something cannot be adequately measured or modeled, then it does not constitute a proper object for positivist social science. Similarly, an archaeological project may interrogate the placement, content and context of coin hoards to seek to understand the socio-economic behaviour of the hoarders.

Understood in this way, positivism is strongly related to a mechanistic ontology. The social world is a gigantic machine, whose components can be known through the routine collection of data, delivering on a mass of facts that are ordered into explanations through theories and concepts. The business of social science is to explain how this machine works, to predict problems and to offer solutions through either repairing or improving the component parts. Quantitative data and statistical analysis are accordingly fundamental to this approach, because they might be seen as the only effective ways to generate facts.

By contrast, the constructionist or interpretivist world-view emphasizes that knowledge is the product of human activity. How we know the world cannot be separated from what we do in relation to the world. For example, financial crashes occur because of the decisions made by investors and traders. This in turn depends upon the assumptions they make about stock movements, the networks of knowledge and information in which they operate, and the previous experiences of all who are involved. In order to understand such a crash, we need to collect detailed data on the beliefs, behaviours, social networks, etc that underpin financial decision-making. This is typically done by talking to stakeholders, or directly observing their actions, or alternatively by studying ‘inside accounts’ of the crash. This delivers a ‘rich’ set of data for theorizing or conceptual analysis. In Museum Studies, the development and appreciation of a collection relates to owners, directors, as well as audiences. Discussing the aims and expectations of such groups enables closer recognition of the philosophy of such a collection.

Constructionism clearly shares much with a holistic or organismic ontology. It treats the world as a living, developing process, where social actors actively try to make sense of one another’s actions. Understanding the world starts with collecting the different ways that actors engage in sense-making, which are gathered until the analyst feels that they are able to build a coherent account of what happened. Rather than attempting to directly predict events, constructionist social science can offer possible scenarios based on its understanding of past events and ongoing process. Qualitative analysis is the right tool for this job, because it allows for the collection of data of sufficient complexity to generate strong analytic accounts.

Again, many researchers (doctoral to professional) would say that whilst their work may tend towards one position rather than another, it is not a ‘pure’ version of either of the approaches discussed above. It may then be useful in your own research proposal to consider the general approach your research will take rather than tie yourself entirely to one position.

|

|

|

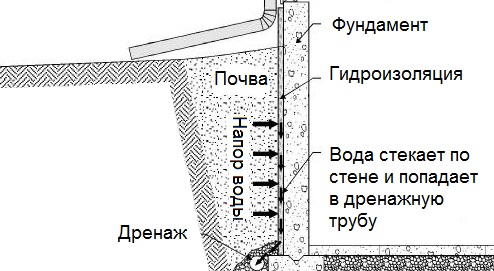

Общие условия выбора системы дренажа: Система дренажа выбирается в зависимости от характера защищаемого...

Своеобразие русской архитектуры: Основной материал – дерево – быстрота постройки, но недолговечность и необходимость деления...

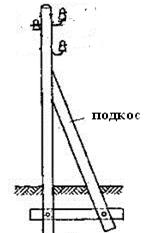

Опора деревянной одностоечной и способы укрепление угловых опор: Опоры ВЛ - конструкции, предназначенные для поддерживания проводов на необходимой высоте над землей, водой...

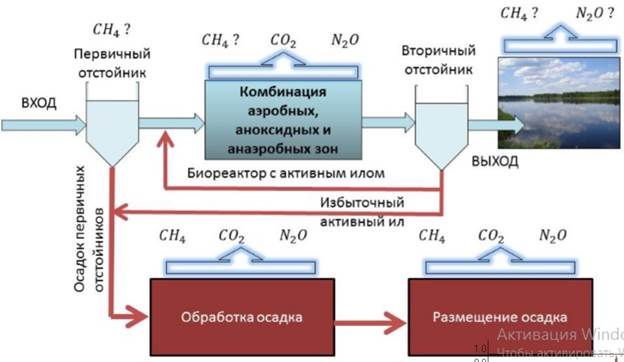

Эмиссия газов от очистных сооружений канализации: В последние годы внимание мирового сообщества сосредоточено на экологических проблемах...

© cyberpedia.su 2017-2024 - Не является автором материалов. Исключительное право сохранено за автором текста.

Если вы не хотите, чтобы данный материал был у нас на сайте, перейдите по ссылке: Нарушение авторских прав. Мы поможем в написании вашей работы!