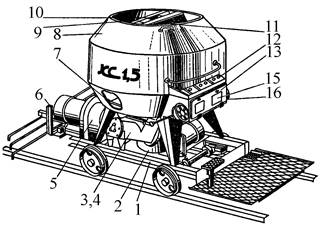

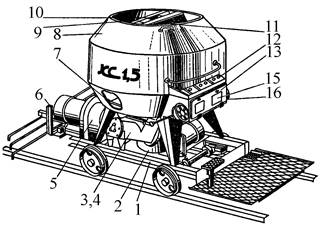

Кормораздатчик мобильный электрифицированный: схема и процесс работы устройства...

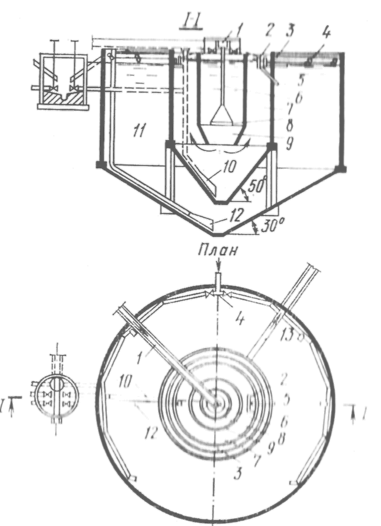

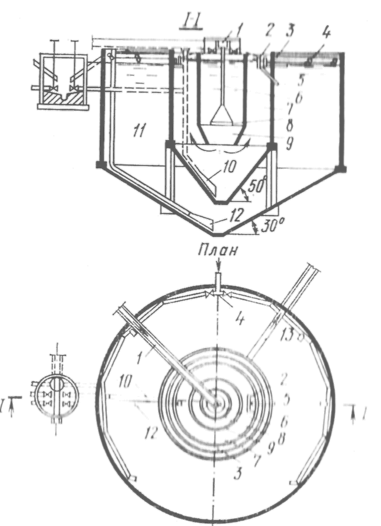

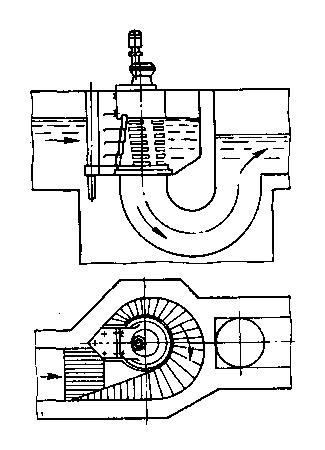

Типы сооружений для обработки осадков: Септиками называются сооружения, в которых одновременно происходят осветление сточной жидкости...

Кормораздатчик мобильный электрифицированный: схема и процесс работы устройства...

Типы сооружений для обработки осадков: Септиками называются сооружения, в которых одновременно происходят осветление сточной жидкости...

Топ:

Методика измерений сопротивления растеканию тока анодного заземления: Анодный заземлитель (анод) – проводник, погруженный в электролитическую среду (грунт, раствор электролита) и подключенный к положительному...

История развития методов оптимизации: теорема Куна-Таккера, метод Лагранжа, роль выпуклости в оптимизации...

Оценка эффективности инструментов коммуникационной политики: Внешние коммуникации - обмен информацией между организацией и её внешней средой...

Интересное:

Берегоукрепление оползневых склонов: На прибрежных склонах основной причиной развития оползневых процессов является подмыв водами рек естественных склонов...

Мероприятия для защиты от морозного пучения грунтов: Инженерная защита от морозного (криогенного) пучения грунтов необходима для легких малоэтажных зданий и других сооружений...

Наиболее распространенные виды рака: Раковая опухоль — это самостоятельное новообразование, которое может возникнуть и от повышенного давления...

Дисциплины:

|

из

5.00

|

Заказать работу |

|

|

|

|

The new monarchy

Henry VII (1485-1509) built the foundations of a wealthy nation state and a powerful monarchy. He based royal power on good business sense and tried to avoid any wars and quarrels with his neighbours and rivals.

- He improved significantly England’s trading position by making an important trade agreement with Netherlands in 1485 at Bosworth, which allowed English to grow again.

- In order to establish his authority, he forbade anyone, except himself, to keep armed men.

- Henry used the Court of Star Chamber, traditionally the king’s council chamber, to deal with lawless nobles by using heavy fines.

- He created a new nobility among merchants and lesser gentry classes in order to have a social standby, which was completely dependent on the Crown.

- He contributed a lot into a creating of English merchant fleet. Was very economical and sensible

Henry VIII (1509 -1547) was quite unlike his father. He was cruel, wasteful with money and interested in pleasing himself.

- He spent a lot of money on maintaining a magnificent court and on wars, so the father’s money was soon gone. He reduced the amount of silver used in coins.

The Reformation

- There were two main reasons for Henry VIII to dislike the power of the Catholic Church in England. This power work against his own authority and the taxes paid to the Church reduced his own income. The other reason was the personal: he wanted to divorce his wife Catherine, which could not give him a son, the pope forbade Henry’s divorce.

- As a result, Henry persuaded the bishops to make him head of the Church and then Parliament passed the Act of Supremacy in 1534. Then Henry VIII divorced Catherine and married his new love, Anne Boleyn.

- He didn’t approve of the new ideas of Reformation Protestantism introduced by Martin Luther and John Calvin, ne still believed in Catholic Faith, so was rewarded by the pope with the title Defender of the Faith.

- But still he forced Parliament to make this break legal, and England became politically a Protestant country.

- Thomas Cromwell became the king’s chief minister. The Crown made a significant reduction of monasteries’ lands and other Church property, most of which were given to the landowners and merchants. This dissolution of the monasteries was the greatest act of official destruction in the history of Britain.

The Protestant-Catholic struggle

Edward VI (1547-1553)

- Most English people still believed in the old Catholic religion. They were not very happy with the new religion.

Mary (1553 - 1558), the Catholic daughter of Catherine of Aragon, became queen in 1553. Her marriage with King Philip of Spain was unwise and unpopular step. Parliament accepted Philip as a king only for Mary’s lifetime. The other mistake was extermination of Protestants by burning. (300 people).

Elizabeth I (1558-1603) wanted to bring together different pars of English society.

- She made the Church part of the state machine by conducting reform (a parish became the unit of state administration; the parish priest – vicar – became as powerful as village squire)

|

|

- She wanted to avoid open quarrels with Catholic France and Spain.

- Elizabeth I kept Mary, The Scottish queen, as prisoner for almost twenty years because she was strong Catholic and the heir to the English Throne. There was a danger from those Catholic nobles, who whished to remove Elizabeth. So she finally executed Mary in 1587, when Mary named Philip as her heir to the throne of England.

England and her neighbours

The new foreign policy

- The main idea of the England’s foreign policy is that the England’s greatest trade rival was also its greatest enemy. Then it was Spain. It refuse to allow England to trade with Spanish American colonies.

- Elizabeth I encouraged to continue to attack and destroy Spanish ships and took a part of treasure.

- Philip decided to conquer England and built a great fleet, an Armada, but English ships were more faster and could shoot further than the Spanish ones. But Spanish Armada was defeated more by bad weather in 1588, than by English guns. It was not an end of the war with Spain.

The new trading empire

- Elizabeth I also encouraged English traders to settle abroad and to create colonies. This led directly to Britain’s colonial empire. There were unsuccessful ttempts to start profitable colonies in Virginia.

- England began selling West African slaves to work for the Spanish in America.

- More chartered companies were established. A charter gave a company the right to all the business in its particular trade or region (the Eastland company in 1579, the Levant Company in 1581, the Africa Company in 1588, the east India Company in 1600).

- Competition with the Dutch in the sphere of spice trade.

Wales

- Henry VII was half Welsh so he aimed not only bring Wales under control, but also to protect its cultural and language originality.

- Henry VIII was only interested in power and authority through direct control. He wanted the Welsh to become English. So he conducted a number of reforms (the question of names). In 1536-1543 Wales became joined to England under one administration, English became the only official language, but Henry gave permission for a Welsh Bible to be printed.

The gathering of poets and singers, known as eisteddfods – the last fortress of Welsh culture, which had been going on since 1170 suddenly stopped.

Ireland

- Henry VIII wanted to bring Ireland under his authority and he persuaded the Irish parliament to recognize him as a king of Ireland. But his attempts to make the Irish accept his English Church reformation failed and led to the noble rebellion against him because in Ireland the Church were still an important part of economic and social life.

- During the Elizabeth’s reign there was a number of Irish rebellions, encouraged by Spanish and French soldiers, which were stifled with great cruelty.

- There were four wars to make Irish accept English authority and religion. At last the old Gaelic way of life was destroyed completely and English government was introduced.

- The English first important colony. Land were taken and sold to English and Scottish merchants. The native Irish were forced to leave or to work for these settlers.

Scotland

- The Scottish monarchs tried to introduce the same kind of centralized monarchy that the Tudors had developed. But they are much more weak, so they preferred not to be cruel with their own disobedient population, because they were the best fighters and could help him in battle against the English.

|

|

- The Scottish kings avoided war with England. One time they had peace relations, but Henry VIII wanted Scottish to accept his authority. In 1513 his army destroyed the Scottish one at Flodden.

- There was no unity among the Scottish nobles (friendship with England or Catholic France?), but the army of Henry VIII persuaded the Scottish James V to accept Henry’s authority in 1543 (the marriage agreement).

- Ordinary Scotts were most unhappy of this situation, so Scottish Parliament turned down the marriage agreement.

- Mary Queen of Scots married the French king’s son in 1558. She was Catholic, but Scotland became Protestant.

- The monarch had no authority over the Kirk. The new Kirk was more democratic and based on the idea that education was important for everyone in Scotland. The new Kirk disliked Mary and her Catholicism.

- James VI brought the Catholic and Protestant nobles and also the Kirk more or less under royal control. He gained the English throne in 1603? As Elizabeth I died unmarried.

Government and society

TudorParliaments

- The Tudor monarchs did not like governing through Parliament. They called it together from time to time as they had a particular job for it. But by using Parliament to strengthen their policy, they actually increased Parliament’s authority.

- Tudor monarchs didn’t get rid of Parliament because they needed money and they needed the support of the merchants and the landowners.

- Power moved from the House of Lords to the House of Commons: the MPs in the Commons represented richer and more influential classes than Lords. During the 16th century the size of the Commons nearly doubled.

- Parliament didn’t represent the people as the MPs didn’t usually live in the area they represented and used to support royal policy rather than the wishes of their electors.

- The Crown appointed a Speaker in order to control discussions in Parliament.

- There were three main things Parliament was supposed to do: agree to the taxes needed, makes the laws which the Crown suggested, advise the Crown if it wished.

- MPs were given three important rights: freedom of speech; freedom from fear of arrest and freedom to meet and speak to the monarch.

- Un answered question about the limits of Parliaments power: who should decide what Parliament should discuss (the Crown or Parliament itself). At least Parliament decided it had a right to discuss the question and it resulted in war.

Rich and poor in town and country

- Significant increasing in population (from 2.2 mil in 1525 to 4 mil in 1604) caused the huge problems with food and clothes.

- The price of food and other goods rose steeply, but real wages fell by half.

- It was very to produce enough food for families and to pay the rent for the land for those, who only had 20 acres and less. Many landowners began to fenced off land belonged to the whole village in order to develop sheep farming. As a result many poor people lost the land they farmed. The government tried to control enclosures but without much success. Dissolution the monasteries, which gave employment and provided food for the very poor, made the situation worse. In 1536 large numbers of people marched to London, but this Pilgrimage of Grace was cruelly put down.

- There were a lot of homeless wandering people on the roads, hungry people began to steel foods. There were several attempts to improve the situation (1547 – any person found homeless a second time could be executed; 1563 – JPs became responsible for deciding on fair wages and working hours, workers were not allowed to move from the parish where they had been born without permission), but they were not successful until 1601, when the first Poor Law was passed. This made local people responsible for the poor in their own area. (raising money in the parish to provide food, housing and work for the poor and homeless).

- England destroyed the Flemish clothmaking industry.

- Using the coal allowed to replace longbow with the muskets, which were not so effective, but gunpowder and bullets were cheaper than arrows.

|

|

- The new industries began to develop in both Birmingham and Manchester

Domestic life

- English women had much more freedom than anywhere else in Europe, but still their life were hard because of birth of many children without any professional help, that often resulted in death. The marriage was often an economic arrangement. After the dissolution of the monasteries the life of unmarried women became dreary.

- Lived in small family groups. People expected to work hard and to die young.

- But most people had a larger and better home with chimneys in it. Almost everyone doubled their living space.

Language and culture

- People started to consider the London pronunciation as “correct” pronunciation. So educated people began to speak “correct” English, and uneducated people continued to speak the local dialect.

- Literacy increased greatly and by 17th century about half the population could read and write.

- Artistic flowering: England left the Renaissance later than much of Europe because it was an island.

- Most fruitful period in English music, England develop its own special kind of painting, the miniature portrait.

- The literature was England’s greatest art form (Christopher Marlowe, Ben Jonson William Shakespeare)

- “soldier poets” – were true Renaissance men, both brave and cruel, but also highly educated (Sir Edmund Spenser, Sir Philip Sidney)

Vocabulary:

- bitter disappointment – горькое разочарование

- nephew – племянник

- widow – вдова

- the pope – священники

- Act of Supremacy - закон о главенстве английского короля над церковью

- monks and nuns – монахи и монахини

- wandering beggar – странствующие нищие

- dissolution of the monasteries – ликвидация монастырей

- to take a lead in religious matters – играть ведущую роль в религиозной сфере

- junior ally – младший союзник

- unharmed – невредимый, нетронутый

- parish – церковный приход

- open quarrel – открытая ссора, открытое противостояние

- treasure – сокровище

- were sunk – были потоплены

- were wrecked on– были разрушены, выброшены на

- entirely – всецело, совершенно, сплошь, целиком

- gathering – собрание

- rebellion – восстание

- stifle a rebellion – подавить восстание

- Protestant Scottish Kirk – протестантская церковь в Шотландии

- poor judgement – недальновидность

- strengthen smb’s position – укрепить ч-л позицию

- get rid of – избавиться от

- yeoman fermer – фермер средней руки

- fence off land – отгораживать землю

- enclosure – огораживание общинных земель

- Pilgrimage of Grace – паломничество благодати

- cruelly put down – жестоко подавить

- riot against – бунтовать, бунт против

- apprentice – ученик, подмастерье, отдавать в ученики

- raw wool – немытая шерсть

- spinner – прядильщик

- weaver – ткач, ткачиха

- rye – рожь

- barley – ячмень

- beans – фасоль

- peas – горох

- oats – овес

- longbow – большой лук

|

|

- musket – мушкет

- hand-held gun – ручное орудие

- gunpowder and bullets – порох и пули

- arrows – стрелки

- chimneys – камин

- dreary - мрачный

The nineteenth century

The years of self-confidence

In 1851 Queen Victoria opened the Great Exhibition of the Industries of All Nations inside the Crystal Palace, in London. The exhibition aimed to show the world the greatness of Britain's industry. No other nation could produce as much at that time. At the end of the eighteenth century, France had produced more iron than Britain. By 1850 Britain was producing more iron than the rest of the world together.

Britain had become powerful because it had enough coal, iron and steel for its own enormous industry, and could even export them in large quantities to Europe. With these materials it could produce new heavy industrial goods like iron ships and steam engines. It could also make machinery which produced traditional goods like woollen and cotton cloth in the factories of Lancashire. Britain's cloth was cheap and was exported to India, to other colonies and throughout the Middle East, where it quickly destroyed the local cloth industry, causing great misery. Britain made and owned more than half the world's total shipping. This great industrial empire was supported by a strong banking system developed during the eighteenth century.

The railway

The greatest example of Britain's industrial power in the mid-nineteenth century was its railway system. Indeed, it was mainly because of this new form of transport that six million people were able to visit the Great Exhibition, 109,000 of them on one day. Many of them had never visited London before. As one newspaper wrote, "How few among the last generation ever stirred beyond their own villages. How few of the present will die without visiting London." It was impossible for political reform not to continue once everyone could escape localism and travel all over the country with such ease.

In fact industrialists had built the railways to transport goods, not people, in order to bring down the cost of transport. By 1840 2,400 miles of track had been laid, connecting not only the industrial towns of the north, but also London, Birmingham and even an economically unimportant town like Brighton. By 1870 the railway system of Britain was almost complete. The canals were soon empty as everything went by rail. The speed of the railway even made possible the delivery of fresh fish and raspberries from Scotland to London in one night.

In 1851 the government made the railway companies provide passenger trains which stopped at all stations for a fare of one penny per mile. Now people could move about much more quickly and easily.

The middle classes soon took advantage of the new opportunity to live in suburbs, from which they travelled into the city every day by train. The suburb was a copy of the country village with all the advantages of the town. Most of the London area was built very rapidly between 1850 and 1880 in response to the enormous demand for a home in the suburbs.

Poor people's lives also benefited by the railway. Many moved with the middle classes to the sburbs, into smaller houses. The men travelled by train to work in the town. Many of the women became servants in the houses of the middle classes. By 1850 16 per cent of the population were "in service" in private homes, more than were in farming or in the cloth industry.

The rise of the middle classes

There had been a "middle class" in Britain for hundreds of years. It was a small class of merchants, traders and small farmers. In the second half of the 18 century it had increased with the rise of industrials and factory owners.

In the nineteenth century, however, the middle class grew more quickly than ever before and included greater differences of wealth, social position and kinds of work.

It also included the commercial classes, however, who were the real creators of wealth in the country. Industrialists were often "self-made" men who came from poor beginnings. They believed in hard work, a regular style of life and being careful with money. This class included both the very successful and rich industrialists and the small shopkeepers and office workers of the growing towns and suburbs.

In spite of the idea of "class", the Victorian age was a time of great social movement. The children of the first generation of factory owners often preferred commerce and banking to industry. While their fathers remained Nonconformist and Liberal, some children became Anglican and Tory. Some went into the professions. The very successful received knighthoods or became lords and joined the ranks of the upper classes.

|

|

Those of the middle class who could afford it sent their sons to feepaying "public" schools. These schools aimed not only to give boys a good education, but to train them in leadership by taking them away from home and making their living conditions hard. These public schools provided many of the officers for the armed forces, the colonial administration and the civil service.

The growth of towns and cities

The escape of the middle classes to the suburbs was understandable. The cities and towns were overcrowded and unhealthy. One baby in four died within a year of its birth. In 1832 an outbreak of cholera, a disease spread by dirty water, killed 31,000 people. Proper drains and water supplies were still limited to those who could afford them.

In the middle of the century towns began to appoint health officers and to provide proper drains and clean water, which quickly reduced the level of disease, particularly cholera. These health officers also tried to make sure that new housing was less crowded. Even so, there were many "slum" areas for factory workers, where tiny homes were built very close together. The better town councils provided parks in newly built areas, as well as libraries, public baths where people could wash, and even concert halls.

Some towns grew very fast. In the north, for example, Middlesbrough grew from nothing to an iron and steel town of 150,000 people in only fifty years. Most people did not own their homes, but rented them. The homes of the workers usually had only four small rooms, two upstairs and two downstairs, with a small back yard. Most of the middle classes lived in houses with a small garden in front, and a larger one at the back.

Population and politics

In 1851, an official population survey was carried out for the first time. It showed that the nation was not as religious as its people had believed. Only 60 per cent of the population went to church. The survey also showed that of these only 5.2 million called themselves Anglicans, compared with 4.5 million Nonconformists and almost half a million Catholics. Changes in the law, in 1628 and 1829, made it possible, for the first time since the 17 century, for Catholics and Nonconformists to enter government service and to enter Parliament. In practice, however, it remained difficult for them to do so. The Tory-Anglican alliance could hardly keep them out any longer. But he Nonconformists naturally supported the Liberals, the more reformist party. In fact the Tories held office for less than five years between 1846 and 1874.

In 1846, when Sir Robert Peel had fallen from power, the shape of British politics was still unclear. Peel was a Tory, and many Tories felt that his repeal of the Corn Laws that year was a betrayal of Tory beliefs. Peel had already made himself very unpopular by supporting the right of Catholics to enter Parliament in 1829. But Peel was a true representative of the style of politics at the time. Like other politicians he acted independently, in spite of his party membership. One reason for this was the number of crises in British politics for a whole generation after 1815. Those in power found they often had to avoid dangerous political, economic or social situations by taking steps they themselves would have preferred not to take. This was the case with Peel. He did not wish to see Catholics in Parliament, but he was forced to let them in. He did not wish to repeal the Corn Laws because these served the farming interests of the Tory landowning class, but he had to accept that the power of the manufacturing middle class was growing greater than that of the landed Tory gentry.

Peel's actions were also evidence of a growing acceptance by both Tories and Whigs of the economic need for free trade, as well as the need for social and political reform to allow the middle class to grow richer and to expand. This meant allowing a freer and more open society, with all the dangers that might mean. It also meant encouraging a freer and more open society in the countries with which Britain hoped to trade. This was "Liberalism", and the Whigs, who were generally more willing to advance these ideas, became known as Liberals.

Some Tories also pursued essentially "Liberal" policy. In 1823, for example, the Tory Foreign Secretary, Lord Canning, used the navy to prevent Spain sending troops to her rebellious colonies in South America. The British were glad to see the liberation movement led by Simon Bolivar succeed. However, this was partly for an economic reason. Spain had prevented Britain's free trade with Spanish colonies since the days of Drake.

Canning had also been responsible for helping the Greeks achieve their freedom from the Turkish empire. He did this partly in order to satisfy romantic liberalism in Britain, which supported Greek freedom mainly as a result of the influence of the great poet of the time, Lord Byron, who had visited Greece. But Canning also knew that Russia, like Greece an orthodox Christian country, might use the excuse of Turkish misrule to take control of Greece itself. Canning judged correctly that an independent Greece would be a more effective check to Russian expansion.

From 1846 until 1865 the most important political figure was Lord Palmerston, described by one historian as "the most characteristically mid-Victorian statesman of all." He was a Liberal, but like Peel he often went against his own party's ideas and values. Palmerston was known for liberalism in his foreign policy. He strongly believed that despotic states discouraged free trade, and he openly supported European liberal and independence movements. In 1859-60, for example, Palmerston successfully supported the Italian independence movement against both Austrian and French interests. Within Britain, however, Palmerston was a good deal less liberal, and did not want to allow further political reform to take place. This was not totally surprising, since he had been a Tory as a young man under Canning and had joined the Whigs at the time of the 1832 Reform Bill. It was also typical of the confusing individualism of politics that the Liberal Lord Palmerston was invited to join a Tory government in 1852.

After Palmerston's death in 1865 a much stricter "two party" system developed, demanding greater loyalty from its memhership. The two parties, Tory (or Conservative as it hecame officially known) and Liberal developed greater party organisation and order. There was also a change in the kind of men who hecame political leaders. This was a result of the Reform of 1832, after which a much larger number of people could vote. These new voters chose a different kind of MP, men from the commercial rather than the landowning class.

Gladstone, the new Liberal leader, had been a factory owner. He had also started his political life as a Tory. Even more surprisingly Benjamin Disraeli, the new Conservative leader, was of Jewish origin. In 1860 Jews were for the first time given equal rights with other citizens. Disraeli had led the Tory attack on Peel in 1846, and brought down his government. At that time Disraeli had strongly supported the interests of the landed gentry. Twenty years later Disraeli himself changed the outlook of the Conservative Party, deliberately increasing the party's support among the middle class. Since 1881 the Conservative Party has generally remained the strongest.

Much of what we know today as the modern state was built in the 1860s and 1870s. Between 1867 and 1884 the number of voters increased from 20 per cent to 60 per cent of men in towns and to 70 per cent in the country, including some of the working class. One immediate effect was the rapid growth in party organisation, with branches in every town, able to organise things locally. In 1872 voting was carried out in secret for the first time, allowing ordinary people to vote freely and without fear. This, and the growth of the newspaper industry, in particular "popular" newspapers for the new half-educated population, strengthened the importance of popular opinion. Democracy grew quickly. A national political pattern appeared. England, particularly the south, was more conservative, while Scotland, Ireland, Wales and the north of England appeared more radical. This pattern has generally continued since then. The House of Commons grew in size to over 650 members, and the House of lords lost the powerful position it had held in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Now it no longer formed policy but tried to prevent reform taking place through the House of Commons.

Democracy also grew rapidly outside Parliament. In 1844 a "Co-operative Movement" was started by a few Chartists and trade unionists. Its purpose was self-help, through a network of shops which sold goods at a fair and low price, and which shared all its profits among its members. It was very successful, with 150 Co-operative stores by 1851 in the north of England and Scotland. By 1889 it had over 800,000 members. Co-operative self-help was a powerful way in which the working class gained self-confidence in spite of its weak position.

After 1850 a number of trade unions grew up, based on particular kinds of skilled labour. However, unlike many European worker struggles, the English trade unions sought to achieve their goals through parliamentary democracy. In 1868 the first congress of trade unions met in Manchester, representing 118,000 members. The following year the new Trades Union Congress established a parliamentary committee with the purpose of achieving worker representation in Parliament. This wish to work within Parliament rather than outside it had already brought trade unionists into close co-operation with radicals and reformist Liberals. Even the Conservative Party tried to attract worker support. However, there were limits to Conservative and Liberal co-operation. It was one thing to encourage "friendly" societies for the peaceful benefit of workers. It was quite another to encourage union campaigns using strike action. During the 1870s wages were lowered in many factories and this led to more strikes than had been seen in Britain before. The trade unions' mixture of worker struggle and desire to work democratically within Parliament led eventually to the foundation of the Labour Party.

During the same period the machinery of modern government was set up. During the 1850s a regular civil service was established to carry out the work of government, and "civil servants" were carefully chosen after taking an examination. The system still exists today. The army, too, was reorganised, and from 1870 officers were no longer able to buy their commissions. The administration of the law was reorganised. Local government in towns and counties was reorganised to make sure of good government and proper services for the people. In 1867 the first move was made to introduce free and compulsory education for children. In fact social improvement and political reform acted on each other throughout the century to change the face of the nation almost beyond recognition.

Queen and monarchy

Queen Victoria came to the throne as a young woman in 1837 and reigned until her death in 1901. She did not like the way in which power seemed to be slipping so quickly away from the monarchy and aristocracy, but like her advisers she was unable to prevent it. Victoria married a German, Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg, but he died at the age of forty-two in 1861. She could not get over her sorrow at his death, and for a long time refused to be seen in public.

This was a dangerous thing to do. Newspapers began to criticise her, and some even questioned the value of the monarchy. Many radicals actually believed the end of monarchy was bound to happen as a result of democracy. Most had no wish to hurry this process, and were happy to let the monarchy die naturally. However, the queen's advisers persuaded her to take a more public interest in the business of the kingdom. She did so, and she soon became extraordinarily popular. By the time Victoria died the monarchy was better loved among the British than it had ever been before.

One important step back to popularity was the publication in 1868 of the queen's book Our life in the Highlands. The book was the queen's own diary, with drawings, of her life with Prince Albert Balmoral, her castle in the Scottish Highlan, delighted the public, in particular the growing middle class. They had never before know-anything of the private life of the monarch, and they enjoyed being able to share it. She referred to the Prince Consort simply as "Albert", to the Prince of Wales as "Bertie", and to the Princess Royal as "Vicky". The queen also wrote about her servants as if they were members of her family.

|

|

|

Состав сооружений: решетки и песколовки: Решетки – это первое устройство в схеме очистных сооружений. Они представляют...

Наброски и зарисовки растений, плодов, цветов: Освоить конструктивное построение структуры дерева через зарисовки отдельных деревьев, группы деревьев...

Археология об основании Рима: Новые раскопки проясняют и такой острый дискуссионный вопрос, как дата самого возникновения Рима...

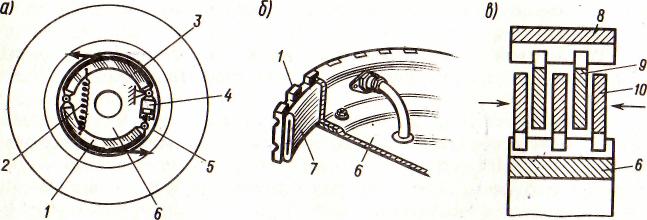

Автоматическое растормаживание колес: Тормозные устройства колес предназначены для уменьшения длины пробега и улучшения маневрирования ВС при...

© cyberpedia.su 2017-2024 - Не является автором материалов. Исключительное право сохранено за автором текста.

Если вы не хотите, чтобы данный материал был у нас на сайте, перейдите по ссылке: Нарушение авторских прав. Мы поможем в написании вашей работы!