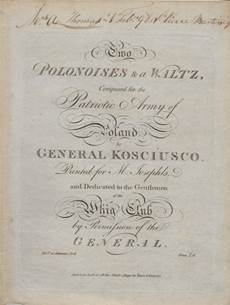

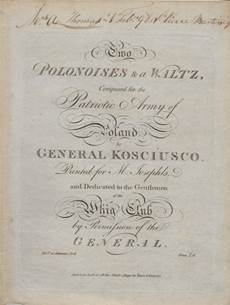

Фронтиспис издания музыкальных произведений, приписываемых Костюшко

Фронтиспис издания музыкальных произведений, приписываемых Костюшко

| |

Костюшко был очень увлечен музыкой – он любил выступления других и, как сообщается, сам играл на пианино. Но в польской традиции он также считается автором так называемого Полонеза Костюшко, что заставляет нас спросить: был ли Костюшко также композитором?

Интригующая история восходит к музыкальной гравюре 1798 года под названием "два Полонеза и Вальс", сочиненной для патриотической армии Польши генералом Костюшко. Документ, хранящийся сегодня в Национальной библиотеке в Варшаве, первоначально принадлежал некоей миссис А. Томас, которая в то время жила в Сен-Пьере на французском острове Мартиника. Интересно, что город был разрушен извержением соседнего вулкана в 1902 году. Катастрофа, по-видимому, пощадила документ, так как он каким-то образом попал в антикварный книжный магазин в Варшаве, а полвека спустя, в 1955 году, был куплен Национальной библиотекой.

Мало что известно о том, как рукопись попала в руки миссис Томас, но первоначально она была посвящена членам клуба вигов, Британской ассоциации, которая в конце 18-го века сочувствовала видению Джорджа Вашингтона о независимости Америки. Вполне вероятно, что на момент его публикации Костюшко находился в Великобритании.

Ноты содержали два Полонеза и вальс, все три якобы написаны Костюшко. Самый интересный из них, ранее упомянутый Полонез, сыграл важную роль в польской истории, занимая видное место в патриотическом польском саундтреке 19-го века и став вдохновением для многих других музыкальных произведений. Но действительно ли ее сочинил Костюшко?

Как и в случае с другими фрагментами рукописи, неясно, кто на самом деле написал Полонез Костюшко. По словам Томаша Куклы, проанализировавшего историю рукописи и произведения, мелодия, безусловно, существовала в 1792 году, но могла быть написана и раньше. Популярная в то время версия, которая начиналась строками " Podróż twoja nam niemiła [мы вздыхаем с горем при вашем отъезде]", связывает происхождение произведения с решением Костюшко отправиться в изгнание после польско-русской войны 1792 года. Таким образом, песня была спета как прощание с Костюшко, когда он отправился в Лейпциг.

Большинство источников указывают на А. Я. Барчицкого из Люблина, но другие возможные претенденты включают М. К. Огинского (известного композитора Полонезов) и некоего Бадовского. Все это делает весьма сомнительным весь вопрос об авторстве Костюшко двух Полонезов (с вальсом дело обстоит еще более фальшиво). В этом смысле название "Костюшко Полонез" мало чем отличается от "мазурки" Домбровского или "Марша Понятовского" – двух других известных песен, музыка которых, конечно, не была сочинена их одноименными героями из польской истории.

В общем, вероятность того, что именно Костюшко сочинил Полонез, очень мала, если только, как утверждает Кукла, мы не истолкуем слово "сочинил" в ином смысле, чем "сложил" или "устроил".:

В свете вышеизложенных аргументов не будет преувеличением предположить, что наш герой не сочинял эти произведения в современном смысле слова, а просто переложил существующие мелодии. Эта интерпретация была бы подтверждена простотой расположения, стремясь указать на работу любителя, а не опытного композитора.

Так что эти кавычки действительно нужны, чтобы написать, что именно Костюшко "сочинил" Полонез "Костюшко". Что касается вальса, Кукла утверждает, что это наиболее вероятная из трех пьес, которые на самом деле были первоначально написаны Костюшко, поскольку рукопись миссис Томас-единственное место, где она появилась.

Художник стер

Урна с сердцем Тадеуша Костюшко в Королевском замке в Варшаве, 1927 год, Источник: национальный цифровой архив (НАК)

Урна с сердцем Тадеуша Костюшко в Королевском замке в Варшаве, 1927 год, Источник: национальный цифровой архив (НАК)

| |

Так почему же мы так мало знаем о художнике Костюшко? Почему этот важный аспект его жизни не стал частью нашего повествования о жизни этого великого героя-наряду с его великими достоинствами как инженера, солдата и государственного деятеля?

Ответ ведь может быть довольно простым. Как утверждает Вальдемар Оконь, Костюшко было очень трудно стать художником просто потому, что это был не тот образ, который был нужен нации.

Игначак, кажется, согласен, указывая на низший статус искусства и его несоответствие патриотическим идеалам нации, поглощенной борьбой за выживание:

Информация о художественных интересах не подходила для изображения национального героя. Учеба в Королевской академии живописи и скульптуры в Париже явно не вязалась с образом идеального

патриота. Многие историки считали, что художественная деятельность находится ниже великого полюса. Активное участие в борьбе за независимость было единственным путем к героизму. Интересы искусства-ничтожные с точки зрения масс - были связаны со слабостью, с поиском личной выгоды и личной славы, с отвлечением внимания от самого главного: сохранения национальной самобытности

Более того, как утверждает Оконь, из основных патриотических повествований биографии Костюшко стиралось не только искусство. Процедура стирания распространялась на элементы его психологического облика и личности, так как некоторые черты его характера, такие как "меланхоличная и торжественная душа художника", последовательно стирались из популярного образа Косцишушко, как не "подобающие монументальной фигуре последнего из Макабеев". Вместо этого, как утверждает Оконь:

Его соотечественники, действуя со всей добросовестностью и с дружескими намерениями, последовательно вписывали Костюшко-художника в круг национальных страданий, представляя мифологизированные биографические сцены и нарисованные или напечатанные через замочную скважину изображения полководца, лежащего одетым в драпированные одежды древнего героя, который "много страдал".

Тадеуш Костюшко - художник, 2017, альбом

Тадеуш Костюшко - художник, 2017, альбом

| |

Костюшко, возможно, не был величайшим художником... и все же его склонность и чувствительность к искусству и музыке, а также его талант к ремеслам выделяют его среди многих других деятелей того времени и, кажется, являются важной и очень необходимой частью в нашем понимании его характера и личности. Наряду с другими важными составляющими его чертами, такими как нравственная целостность, целомудрие и праведность, которые проявляются в актах воздержания от любого ненужного насилия и стремлении к равенству для всех, эта художественная сторона кажется подходящим и необходимым элементом в личности конечного польского героя.

Автор: Миколай Глинский, апрель 2018; Библиография: Тадеуш Костюшко-художник (PWM, 2018), с эссе Павла Игначака и Адама т. куклы; Вальдемар Оконь, Костюшко

Was Kościuszko an Artist?

Author: Mikołaj Gliński

Published: May 26 2019

Tadeusz Kościuszko was a soldier, politician and one of Poland's greatest national heroes of all time. But did you know about Kościuszko the artist? And what are the odds that he was also a composer?

It doesn’t come across too often that a military leader and politician is also a man of arts. Yet this might have been the case with Polish national hero Tadeusz Kościuszko. Arts and music accompanied him for most of his life and the works attributed to him weaved their way into Polish history. Just how fine an artist was Kościuszko? And what does his art tell us about the man? Lastly, why had you never heard about Kościuszko the artist in the first place?

Kościuszko & the fly

An anecdote has it that, in 1765, King Stanisław August visited Warsaw’s Corps of Cadets, a military school he had established a year earlier. Kościuszko was studying there at the time. He saw the cadet’s drawings and was much impressed. He praised Kościuszko’s talent and encouraged the young man to develop his skills in this direction. Then he suddenly noticed a splattered fly on one of the papers… Irritated, he advised the young artist to look after his exercise books more carefully. In response, Kościuszko pointed out to the king that the fly was not splattered onto the page, but drawn onto it.

The anecdote, as art historian Waldemar Okoń suggests, is rather untrustworthy: it appears only in one source and is suspiciously reminiscent of ancient Greek anecdotes illustrating the unsurmounted realist skills of some of the greatest Greek painters. But there’s also another reason to dismiss it: based on some of Kościuszko’s extant drawings from that period, we can surely say that mimetic hyper-realist excellence was certainly not Kościuszko’s forte as an artist…

A portrait of the artist as a young man… in Warsaw

Most biographers do agree however that Kościuszko manifested a talent early on for drawing and painting, a passion which he developed while studying at Warsaw’s Corps of Cadets, a military state school where apart from learning languages, literature and geography, the cadets were taught swordsmanship, military history, geometry... and drawing. An extant report from his 1766 examinations mentions that the student Kosciuszko distinguished himself specifically in drawing class (Handszeichnung), earning him the commendable ‘score’ of podbrygadier.

Yet a look at some of the surviving drawings from that period could give one quite a confounding impression. This is the case when one looks at the illustration Kościuszko made for a handbook about transportation in the army by A.L. Oelsnitz, one of the school professors. His representation of soldiers doing differents chores against a rural landscape betrays an unsure hand and, according to art historian Paweł Ignaczak, is ‘a typical work by an inexperienced amateur, with anatomical errors, a characteristic stiffness of poses and gestures, and disturbed spatial relations, revealing shortcomings in the artist’s mastery of perspective’.

One can’t stop but wonder how the same person could have drawn an almost perfect portrait of a man in Spanish costume: ‘a realistic portrait of enhanced psychology, with well captured gestures and a clear differentiation of textures of particular objects’. As it turns out, explaining the contrast between this work and the inept frontispiece of Olesnitz’s manuscript may be simpler than one would think. The portrait was based on a copperplate engraving by Paul Pontius depicting the dutch sculptor Hendrik van Balen, itself a print designed by the great Anton van Dyck. Thus, in the case of the portrait, Kościuszko had simply copied the work – and done this with great neatness indeed.

According to Ignaczak, this shows that Kościuszko-the-artist was back then ‘quite accomplished as a copyist, although he was rather at sea in independent drawing’. It is very likely that because of this shortcoming, as the scholar suggests, Kościuszko decided to study at the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture in Paris.

Learning the craft in Paris

Kościuszko left for France in 1769 on a royal scholarship and immediately enrolled at the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture, one of the finest art schools of the era. Although he eventually quit the course after only a year, the drawings remaining from that period suffice to tell us something about Kościuszko the artist.

In France, Kościuszko would undergo a programme that began with copying works of graphic art, then executing sketches of ancient sculptures, before producing portraits of live models. Only then would Kościuszko set about creating his own compositions in drawing and painting.

This process, as Ignaczak argues, is confirmed by his surviving works, most of which have come down to us as part of the collection of the Czartoryski Museum in Kraków. Of the 20-odd drawings, probably more than half come from when Kościuszko was at the Parisian academy (however, the collection includes drawings predating this period as well as those made some 20 years later). Besides ink and watercolour drawings of imaginary landscapes, there are mostly crayon drawings. Among these there are mostly nudes (all male apart from one female subject) – and, as Ignaczak claims, probably copies of drawings by masters or prints reproducing them.

This seems clear when one looks at a drawing of a reclining female nude that replicates the composition of a small pastel by Francois Boucher. Ignaczak comments:

Executed quite freely, at first glance they give the impression of having been made by a first-class drawer. It is only when we compare these works with others we realise that their excellence is based on the perfect copying of models.

Another drawing from the Parisian period called Composition of Ancient Roman Buildings can also be seen as proof of Kościuszko’s copying and combining talents – but not his gift of observation and rendition. As Ignaczak suggests, the drawing belongs to the popular genre known as ‘architectural caprice’, in which an artist combines relics standing in different places in Rome and Italy into a single composition. This means that in order to draw this Roman landscape, with the remains of the Temple of Castor and Pollux, the Pantheon, the temple at Tivoli and the Pyramid of Cestius, Kościuszko had certainly no need to travel to Rome. He simply combined elements he knew from other drawings into a new composition. Ignaczak finds that the drawing is executed quite competently although there are ‘weaker parts, such as the rather poor curve of the Pantheon’s Dome and the strange shape of the Belvedere torso.’

Tadeusz Kościuszko Artist – Image Gallery

The depiction of Christ on the Cross features some physical imperfections, which render Christ’s posture on the cross quite unrealistic... or very metaphysical. In any case, the image made one Polish critic some hundred years later come up with quite a sacrilegious theory, namely that Kościuszko’s Christ is not really Christ, but rather a symbol – a symbol of the crucification of Poland.

As Ignaczak writes, independent compositions were not really Kościuszko’s forte:

Read more A decent copyist – the studies in Paris helped him to hone these skills.

The artist in idyllic Rome

Perhaps the best in the collection are the four ink and watercolour drawings of Roman landscapes. Made most likely in the early 1790s – some 20 years after his studies in Paris – they can be seen as proof of Kościuszko’s evolving talent as an artist, even if by then he had turned to the duties of an officer, engineer and statesman. And if, as one theory argues, they were indeed made during Kościuszko’s short stay in Rome in 1793 (that is, just before the eponymous insurrection he would lead a year later), they would also prove that Kościuszko’s ability to paint what he observed also developed.

These drawings, along with the earlier Triumph of Flora (circa 1788) – a bucolic scene depicting a flower-adorned dancing procession celebrating the festival of the Roman goddess Vesta against an idealised landscape – also testify to Kościuszko’s ongoing fascination with the ideals of ancient classical aesthetics, as perceived by the people of the Enlightenment.

According to Ignaczak, Kościuszko’s artistic work is rooted strongly in the 18th-century mentality, but it also adheres to the cultural model of early romanticism. Another Kościuszko expert, Waldemar Okoń, highlights his persistently strong proclivity for the sentimental-rococo tradition, whereas the overall character of his artistic persona shares affinities with the ideals of the Sturm und Drang period in Germany.

Kościuszko the artisanal craftsman

According to most sources, the decision to quit art school was caused by Kościuszko’s ‘disappointment and disillusionment’ with his talents. Instead he turned to engineering studies – an education that would become his profession (and a great asset when he later went to America). He eventually spent another three years studying in Paris before returning to Poland in 1774. And yet, even throughout this period, he maintained his interests in fields that required artistic theory and practice, such as landscape gardening and woodcarving.

He also never gave up on drawing (he was especially fond of portraying women) and arts continued to play an important role in his life. In most places where he lived, some form of handicraft was always his favourite past-time. On his estate in Siechnowicze, he carved trays and plates out of applewood. In Russia, where he found himself captive following the fall of the uprising, he passed the time in jail making little objects, like a sugar bowl from coconut and sheet metal. He also made a snuff box and a box for tobacco, even though he himself was free from these bad habits (coffee was his only addiction).

Tadeusz Kościuszko as Artist and Artisan – Image Gallery

In England, where Kosciuszko was recovering after imprisonment in St Petersburg, British painter Benjamin West paid him a visit and recalled how Kościuszko, reclining on a couch, with a black silk band round his head, ‘was drawing landscapes, which is his principal amusement’. In France, his daily routine included regular hours of painting or turnery after dinner. The objects he produced – snuff boxes, sugar boxes or candle holders – would then be offered as gifts to friends and acquaintances.

Kościuszko took his drawing talents with him to America, where, in his spare time away from fighting, he gained a reputation as a skillful portrait artist. He later recalled how one high-society lady threatened to hit him with a shovel if he didn’t draw her likeness. He did the drawing but had to resort to taking flight later. During his second stay in America, Kościuszko painted a likeness of his friend Thomas Jefferson – the work did not survive but the colour aquatint by Michał Sokolnicki is considered a faithful copy.

It might be important to note that Kościuszko also indulged in handicrafts throughout his whole life, including those that required especially painstaking meticulousness and patience, like crochet (he crocheted a neat money bag in the shape of a rogatywka) and embroidery (there’s a surviving tapestry made by Kościuszko using cross-stitch).

Notably, all these tactile interests should be seen in contrast to his lack of interest in writing. Despite continually producing artistic objects throughout his life, he left very few words for historians to also savour. That being said, Kościuszko may well have put pen to paper when it came to another artistic medium.

Was Kościuszko a composer?

The frontispiece from the edition of music pieces attributed to Kościuszko; Photo: Polona.pl

Kościuszko was very keen on music – he enjoyed performances by others and reportedly played the piano himself. But in Polish tradition, he’s also regarded as the author of the so-called Kościuszko Polonaise, which leads us to ask: was Kościuszko a composer too?

The intriguing story goes back to a music print from 1798, under the title Two Polonoises and Waltz Composed for the Patriotic Army of Poland by General Kosciusco. Held today in the National Library in Warsaw, the document was originally owned by a Mrs A. Thomas, who at the time lived in Saint Pierre on the French Island of Martinique. Interestingly, the town was destroyed by the eruption of a nearby volcano in 1902. The catastrophe presumably spared the document as it somehow found its way into an antiquarian bookstore in Warsaw and a half century later in 1955 was bought by the National Library.

Little is known about how the manuscript landed in Mrs Thomas’ hands, but it was originally dedicated to the members of the Whig Club, a British association that in the late 18th century sympathised with George Washington’s vision for America’s independence. It’s likely that at the time of its publication, Kościuszko was in Great Britain.

The notes contained two polonaises and a waltz, all three allegedly composed by Kościuszko. The most interesting of them, the previously-mentioned polonaise, had gone on to play an important role in Polish history, featuring prominently in the 19th-century patriotic Polish soundtrack and becoming an inspiration for many other musical pieces. But was it really composed by Kościuszko?

As with other pieces from the manuscript, it is uncertain who actually wrote the Kościuszko Polonaise. According to Tomasz Kukla, who analysed the history of the manuscript and the piece, the melody was certainly in existence in 1792, but it could have been written even earlier. The version popular at the time, which started with the lines ‘Podróż twoja nam niemiła [We sigh with woe upon your departure]’ links the origins of the piece with Kosciuszko’s decision to go into exile following the Polish-Russian War of 1792. As such, the song was sung as a farewell to Kościuszko as he set off for Leipzig.

Most sources point to an A.J. Barcicki of Lublin, but other possible contenders include M.K. Ogiński (a renowned composer of polonaises) and a certain Badowski. All of this makes the whole issue of Kościuszko’s authorship of the two polonaises rather doubtful (the thing is more spurious with the waltz). In this sense, the title Kościuszko Polonaise does not differ much from Dąbrowski’s Mazurka or Poniatowski’s March – two other famous songs whose music was certainly not composed by their eponymous heroes from Polish history.

All in all, there’s really little chance that it was Kościuszko who composed the polonaise, unless, as Kukla argues, we interpret the word ‘composed’ in a different sense, that of ‘put together’ or ‘arranged’:

In light of the arguments set out above, it would not be an abuse to suppose that our hero did not compose these works in the present-day sense of the word but merely arranged existing melodies. That interpretation would be borne out by the simplicity of the arrangement, tending to indicate the work of an amateur rather than an experienced composer.

So one really needs those quotation marks to write that it was Kościuszko who ‘composed’ the ‘Kościuszko’ Polonaise. As for the waltz, Kukla claims that is the most likely of the three pieces to actually be originally written by Kościuszko, since Mrs Thomas’ manuscript is the only place where it has appeared.

Artist erased

So why then do we know so little about Kościuszko the artist? Why hasn’t this important aspect of his life become part of our narrative about the life of this great hero – along with his great assets as an engineer, soldier and statesman?

The answer after all may be quite simple. As Waldemar Okoń argues, it was very difficult for Kościuszko to have become an artist simply because this was not the image of him that the nation needed.

Ignaczak seems to concur, pointing to the inferior status of art and its being incongruous with the patriotic ideals of a nation absorbed in a struggle for survival:

Information about artistic interests was not suited to the portrayal of a national hero. Studies at the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture in Paris apparently did not sit well with the image of an ideal patriot. Many historians considered that artistic activities were beneath a great Pole. Active participation in the struggle for independence was the only path to heroism. Art interests – trifling from the point of view of the masses – were associated with weakness, with seeking personal gain and private renown, and with diverting attention away from the most crucial thing: to preserve the national identity

Moreover, as Okoń argues, it wasn’t only art that was being erased from the mainstream patriotic narratives of Kościuszko’s biography. The erasure procedure stretched over to elements of his psychological make-up and personality, as some features of his character, like the ‘melancholy and solemn soul of the artist’ were consistently wiped out from the popular image of Kościszuszko as not ‘befitting the monumental figure of the last of the Macabees’. Instead, as Okoń claims:

His compatriots, acting in all good faith and with friendly intentions, consistently inscribed Kościuszko-the-artist into the circle of national suffering, presenting a mythologised biographical scenes and painted or printed through-a-keyhole images of the commander lying down clothed in the draped robes of an ancient hero who has ‘suffered much’.

Kościuszko may not have been the greatest artist… And yet his propensity and sensitivity for art and music as well as his talent for handcrafts sets him apart from many other figures of the time, and seems to be an important and much needed part in our understanding of his character and personality. Along with his other important constituent features like moral integrity, chastity and righteousness – which manifested themselves in acts of refraining from any unnecessary violence and the pursuit of equality for all – this artistic side seems like an apt and necessary element in the personality of the ultimate Polish hero.

Written by Mikołaj Gliński, April 2018; Bibliography: Tadeusz Kościuszko- Artist (PWM, 2018), with essays by Paweł Ignaczak and Adam T. Kukla; Waldemar Okoń, Kościuszko

Фронтиспис издания музыкальных произведений, приписываемых Костюшко

Фронтиспис издания музыкальных произведений, приписываемых Костюшко

Урна с сердцем Тадеуша Костюшко в Королевском замке в Варшаве, 1927 год, Источник: национальный цифровой архив (НАК)

Урна с сердцем Тадеуша Костюшко в Королевском замке в Варшаве, 1927 год, Источник: национальный цифровой архив (НАК)

Тадеуш Костюшко - художник, 2017, альбом

Тадеуш Костюшко - художник, 2017, альбом