Организация стока поверхностных вод: Наибольшее количество влаги на земном шаре испаряется с поверхности морей и океанов (88‰)...

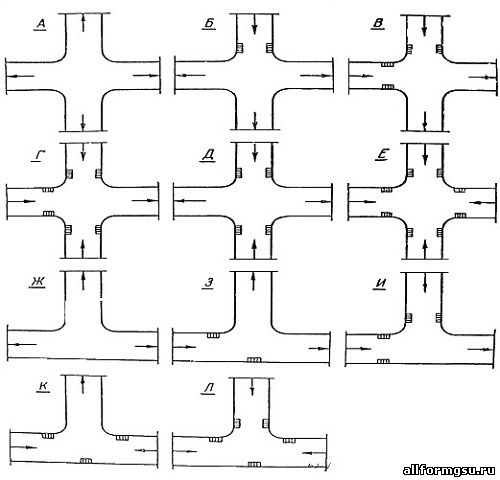

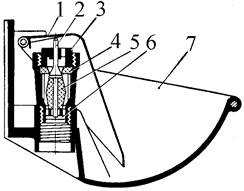

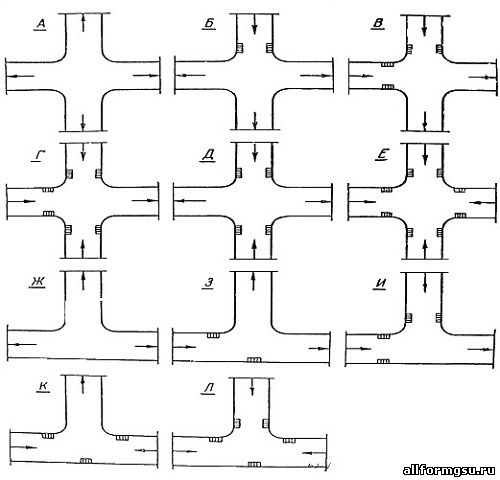

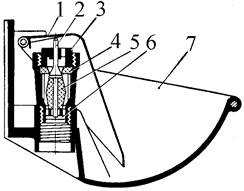

Индивидуальные и групповые автопоилки: для животных. Схемы и конструкции...

Организация стока поверхностных вод: Наибольшее количество влаги на земном шаре испаряется с поверхности морей и океанов (88‰)...

Индивидуальные и групповые автопоилки: для животных. Схемы и конструкции...

Топ:

Особенности труда и отдыха в условиях низких температур: К работам при низких температурах на открытом воздухе и в не отапливаемых помещениях допускаются лица не моложе 18 лет, прошедшие...

Методика измерений сопротивления растеканию тока анодного заземления: Анодный заземлитель (анод) – проводник, погруженный в электролитическую среду (грунт, раствор электролита) и подключенный к положительному...

Интересное:

Финансовый рынок и его значение в управлении денежными потоками на современном этапе: любому предприятию для расширения производства и увеличения прибыли нужны...

Национальное богатство страны и его составляющие: для оценки элементов национального богатства используются...

Лечение прогрессирующих форм рака: Одним из наиболее важных достижений экспериментальной химиотерапии опухолей, начатой в 60-х и реализованной в 70-х годах, является...

Дисциплины:

|

из

5.00

|

Заказать работу |

|

|

|

|

2) persons under an obligation to keep classified information confidential with regard to circumstances to be kept confidential, unless they have been released from the obligation to keep confidentiality under applicable provisions of law;

Clergymen with regard to facts revealed under the seal of confession.

Article 83. [Privilege to refuse testimony] § 1. No person has the privilege to refuse his testimony as a witness, except for the party’s spouse, ancestors, descendants and siblings of the party as well as first-degree relatives by marriage and persons being in an adoptive, wardship or guardian relationship with the party. The privilege to refuse testimony shall survive the dissolution of marriage, adoption, wardship or guardianship.

§ 2. The witness may refuse to answer a question, if the answer would expose him or his nearest listed in § 1 to criminal liability, disgrace or direct material damage or shall cause the infringement of the obligation to keep legally protected professional secret.

Before hearing testimony, the public administration authority shall instruct the witness of his privilege to refuse testimony and answers to questions and liability for perjury.

The mediator shall not testify as to facts which came to his knowledge in connection with the conducted mediation, unless he is released from the duty to keep mediation secrecy by the participants in the mediation.

Article 50. [Purpose of summons] § 1. A public administration authority may summon persons to participate in the actions undertaken and to give explanations and testimony personally, through an attorney-in-fact, in writing or in the form of an electronic document, if it is necessary to decide the matter or perform official actions. [...]

Article 67. [Actions recorded in the minutes] § 1. Each public administration authority shall draw up concise minutes of any action undertaken in the proceedings having vital significance for deciding the matter, unless the action has been in other manner recorded in writing.

§ 2. In particular, the minutes shall record:

2) the examination of a party, witness and expert;

Issue No. 8 “The nihility of an administrative act, including the legal consequences of holding the act void”

The concept of so-called non-act or non-existent legal act is not regulated by Polish administrative law, but it is known in literature and case law, also in the field of civil law. The doctrine indicates that the sanction of invalidity is attributed to existing legal actions. It is argued that non-existent decisions occur when the behavior only appears to be a legal act, and when the external factual state of the legal act does not exist, i.e. action that is recorded in the consciousness of the environment as a specific legal act. In the first case, there is a will to take action, but one of its constitutive conditions is missing. In the second, there is no such appearance, because the entities performing the activities had no intention of producing legal effect.

|

|

Therefore it is necessary to distinguish a non-act from invalid decisions. The constitutive elements of a non-existent legal act, including acts of applying the law, are the occurrence of a factual event that only creates the appearance of a legal act because of the form, time and place of origin, and the entity that took it. This situation can arise in two cases: when a decision was issued in non-existent proceedings or when a non-existent decision was issued in legally existing proceedings. The first case occurs when the entity that undertook or conducts the proceedings is unable to conduct the proceedings or there is a legitimate entity, but no party exists. The second case occurs when the decision has no external legal features or has not been served on the party.

The non-act does not bind either the authorities or the party, hence, to avoid it, it is not necessary to ascertain its defects before its effects. However, an invalid decision is binding until it is annulled pursuant to art. 158 of the Code of Administrative Procedure. Due to these effects, it is important to correctly distinguish between invalid decisions and non-existent legal acts. On the basis of applicable legal regulations, it has been assumed that the most severe sanction that may affect existing acts is the sanction of invalidity. Therefore, even decisions affected by defects of invalidity benefit from the presumption of binding force until they are eliminated from legal circulation. This excludes the adoption of the concept of absolutely invalid administrative decisions, unless the concept is taken to treat non-existent decisions.

It is worth noting, however, that despite the thesis going towards a non-existent legal act, the Polish Supreme Administrative Court prefers to use the institution of annulment in the aforementioned case. Both in the doctrine and in the jurisprudence there is excessive restraint in questioning the legal existence of an administrative decision, considering it to be a non-existent act even when it clearly deviates from the normative model. The reason for this is the legislator's silence as to the reasons for true nullity.

Issue No. 9 “The grounds, procedure and consequences of the repeal of legal and illegal administrative acts”

The administrative decision is correct if it jointly meets two conditions:

1) it complies with the norms of substantive administrative law;

2) it was issued in accordance with the norms of procedural administrative law.

The decision violating substantive or procedural norms is faulty. In the classic doctrine of administrative law, the concept of the correctness of an administrative decision was based on compliance with the norms of substantive administrative law and procedural administrative law in force as of the date of the decision. The modern concept also takes into account the issuance of an administrative decision based on an unconstitutional normative act, and in the scope of an administrative decision issued on the basis of a European law provision declared by the European Court of Justice as invalid, as well as defective in its interpretation.

The administrative decision takes advantage of the presumption of correctness attribute, which means that it is force (is valid) until has been properly eliminated from the legal turnover. This applies to all types of faulty decisions. The recognition of the presumption of correctness of an administrative decision, which can be refuted only in the appropriate manner, means that the existence of administrative decisions invalid by virtue of law in the Polish legal system is questioned. The construction of invalidity by virtue of law itself can be applied only if the legislator expressly provides in the legal provision such an exception from the presumption of correctness of the decision.

|

|

Legal regulations contained in the Code of Administrative Procedure are subject to the presumption of correctness of decisions and they do not introduce any exceptions in this respect. Elimination of an invalid decision from existence can only occur by issuing a decision that annuls such decision. This also applies to the decision containing the defect causing its invalidity by virtue of separate legal provisions to which refers Art. 156 § 1 item 7 of the Code of Administrative Procedure

The institution of annulment is primarily of a substantive nature by establishing a sanction for annulment of a decision affected by severe qualified defects. The institution of annulment of a decision creates the legal possibility of elimination from existence decisions affected primarily by substantive defects, and therefore defects causing incorrect shaping of the substantive law relationship, both in subjective and objective terms.

The institution of annulment of a decision is also of a procedural nature by normalizing the mode of application of the sanction of invalidity and in this respect it is not uniform, because it contains both elements characteristic for an appeal, a supervision measure as well as to a limited extent - revocation of a decision.

Article 156. [Grounds] § 1. A public administration authority shall declare a decision invalid if:

1) the decision has been issued in violation of provisions governing competence;

2) the decision has been issued without legal basis or with gross infringement of law;

3) the decision concerns a matter already decided under another final decision or a matter which has been disposed of without notice by the authority;

4) the decision has been addressed to a person not being a party to the matter;

5) the decision was unenforceable on the day of its issuance and the unenforceability has been permanent,

6) if enforced the decision would cause an offence punishable by penalty; or

7) the decision contains a defect which renders the decision invalid by operation of law.

§ 2. The decision may not be declared invalid for reasons specified in § 1 subsections 1, 3, 4 and 7, if a period of 10 years has elapsed from the day the decision has been served or pronounced or if the decision caused irreversible legal consequences.

Article 157 [Competent authority; form] § 1. In cases specified in Article 156, the decision may be declared invalid by the authority of higher level, and if the decision was issued by a minister or self-government appeal board – by the minister or the board.

§ 2. The proceedings to declare a decision invalid may be initiated upon demand of a party or ex officio. [...]

Article 158. [Continued] § 1. The ruling with respect to the declaration of invalidity of a decision shall be issued by way of a decision. The provisions on disposal of the matter without notice by the authority do not apply.

§ 2. If it is inadmissible to declare a decision invalid due to the circumstances specified in Article 156 § 2, the public administration authority shall only rule that the decision has been issued contrary to the law and shall indicate circumstances which did not permit to declare the decision invalid.

Article 159. [Stay of enforcement] § 1. A public administration authority competent to declare a decision invalid shall ex officio or upon demand of a party order a stay of enforcement of the decision, if it is probable that the decision contains one of the defects specified in Article 156 § 1.

§ 2. A party may file a complaint against an order staying the enforcement of the decision.

|

|

Article 161. [Special powers] § 1. A minister may at any time and within the necessary scope quash or amend any final decision, if a threat to human life or health or significant damage to national economy or material interest of the State may not be eliminated in any other manner.

§ 2. With regard to decisions issued by the authorities of self-government units in matters constituting government administration tasks, the powers specified in § 1 shall be also vested in a voivode.

§ 3. A party which suffered damage as a result of a decision being quashed or amended shall have a claim for damages for the loss actually suffered against the authority which quashed or amended the decision; the authority by means of a decision shall also rule on the claim for damages.

§ 4. The claim for damages shall be time-barred after three years from the day the decision quashing or amending the original decision became final. [...]

Issue No. 10 “Material breaches of procedure of exercising of the administrative procedure, entailing the repeal of an administrative act”

Reopening of the procedure.

Reopening of the procedure is one of the two extraordinary remedies available to a party against a final administrative decision. The remedy is granted when the final decision is so defective that it is justified to depart from the principle of durability of administrative decisions. Pursuant to Article 145.1 of the CAP, procedure in a matter concluded with a final decision shall be reopened if major defects of the procedure have been discovered. Such defects have been fully listed in the above provision. There are eight such major defects, including in particular: (a) the fact that the decision was issued as a result of a criminal offence, (b) the fact that a party, not due to its fault, did not participate in the procedure, and (c) the fact that new factual circumstances or evidence came to light. Other major defects were added to the list in: Article 145a of the CAP, i.e. if the Constitutional Tribunal ruled that a normative act on the basis of which the decision had been issued violated the Constitution (or international treaty) and Article 145b, i.e. if the court ruled that the principle of equal treatment had been breached in compliance with the Act of 3 December 2010 on implementation of certain European Union provisions regarding equal treatment.

The procedure may be reopened ex officio or upon demand of a party (and only upon demand of a party in the case described under letter (b) above).

The application for reopening the procedure should be submitted to the authority which issued the decision in the first instance within one month of the day on which the party discovered the circumstance constituting the ground for reopening the procedure. The procedure is reopened on the basis of an order; the refusal to reopen the procedure is effected by means of a decision.

The reopened procedure may be divided into two stages: (1) stage one – when the authority evaluates the existence of the grounds for reopening and (2) stage two – when the authority rules as to the merits of the matter. The authority having competence in this regard is the authority which issued the decision in the last instance. When resolving the matter, the authority issues a decision in which: (a) refuses to quash the original decision, if no defects listed in Article 145 § 1 exist, or (b) the authority quashes the original decision and issues a new decision resolving the matter as to the merits.

The original decision may not be quashed if a specific period has elapsed from the day the decision has been issued (e.g. with regard to the defect described in point (b) above – a period of 5 years, as to other defects – a period of 5 or 10 years). Also the decision shall not be quashed if, as a result of reopening of the procedure, only a decision corresponding to the merits of the original decision could have been issued. It is also possible to reopen the procedure concerning the issuance of certain orders.

|

|

Article 145. [Grounds] § 1. In a matter concluded with a final decision the proceedings shall be reopened if:

1) evidence upon which factual circumstances material to the matter have been ascertained turned out to be false;

2) the decision was issued as a result of a criminal offence;

3) the decision was issued by an employee who or a public administration authority which should have been disqualified pursuant to Articles 24, 25 and 27;

4) a party, not due to his fault, did not participate in the proceedings;

5) new factual circumstances material to the matter or new evidence existing on the day the decision had been issued came to light, of which the authority issuing the decision was not aware;

6) the decision had been issued without obtaining a position of another authority required by law;

7) a preliminary issue was resolved by a competent authority or common court contrary to the findings made at the issuance of the decision (Article 100 § 2);

8) the decision had been issued on the basis of another decision or court judgment which had been quashed or reversed.

§ 2. The proceedings may be reopened on the grounds specified in § 1 subsections 1 and 2 before the evidence has been found false or the offence has been found to be committed on the basis of a judgment of a court or other authority, if it is evident that the evidence had been falsified or the offence had been committed and the reopening of the proceedings is indispensable in order to prevent a threat to human life or health or significant damage to the public interest.

§ 3. The proceedings may be reopened on the grounds specified in § 1 subsections 1 and 2 if the proceedings before the court or other authority may not be initiated due to the lapse of time or due to other reasons specified in the provisions of law.

Article 145a. [Reopening in case of violation of the Constitution] § 1. The demand to reopen the proceedings is also admissible, if the Constitutional Tribunal ruled that a normative act violated the Constitution, international treaty or statute on the basis of which the decision had been issued.

§ 2. In a case specified in § 1, the demand to reopen the proceedings shall be submitted within one month of the day the judgment of the Constitutional Tribunal takes effect.

Article 145b. [Reopening of the Proceedings] § 1. The demand to reopen proceedings is also admissible, if the court ruled that the principle of equal treatment was breached as set out in the Act of 3 December 2010 on Implantation of Certain European Union Provisions on Equal Treatment (Journal of Laws No. 2016, item 1219), and if the breach of this principle affected the final decision in the matter.

§ 2. In the case specified in § 1, the demand to reopen the proceedings shall be submitted within one month of the day the ruling of the court became legally binding.

Article 146. [Limitations to quash the decision] § 1. The decision may not be quashed for reasons specified in Article 145 § 1 subsections 1 and 2 if a period of 10 years has elapsed from the day the decision had been served or pronounced, and for reasons specified in Article 145 § 1 subsections 3-8 and Article 145a and Article 145b, if a period of 5 years elapsed from the day the decision had been served or pronounced.

§ 2. The decision shall not be quashed also if, as a result of the reopening of the proceedings, only a decision corresponding to the merits of the original decision could have been issued.

Article 147. [Proceedings ex officio and upon application] The proceedings may be reopened ex officio or upon demand of a party. For reasons specified in Article 145 § 1 subsection 4 and Article 145a and Article 145b the proceedings may be reopened only upon demand of a party

Article 148. [Time limit] § 1. The application for reopening the proceedings shall be submitted to the public administration authority which issued the decision in the first instance, within one month of the day the party became aware of the circumstance constituting the ground for reopening of the proceedings.

§ 2. The time limit to submit the application for reopening of the proceedings for the reason specified in Article 145 § 1 subsection 4 shall begin to run on the day the party became aware of the decision.

|

|

Article 149. [Reopening; refusal to reopen] § 1. The proceedings shall be reopened by means of an order.

§ 2. The order shall constitute a basis for the competent authority to conduct the proceedings regarding the grounds for reopening and the disposal of the matter as to the merits.

§ 3. The refusal to reopen the proceedings shall be effected by means of an order.

§ 4. The order specified in § 1 shall be subject to complaint..

Article 150. [Competent authority] § 1. In matters specified in Article 149 the public administration authority which issued a decision in the matter in the last instance shall be competent.

§ 2. If the proceedings should be reopened due to actions of the authority specified in § 1, the decision concerning the reopening of the proceedings shall be taken by the authority of higher level which shall simultaneously designate the authority competent in matters specified in Article 149 § 2.

§ 3. The provisions of § 2 shall not apply, if the decision in the last instance was issued by a minister and – in matters for which the self-government units are competent – by the self-government appeal board.

Article 151. [Reconsideration] § 1. The public administration authority referred to in Article 150, after conducting the proceedings specified in Article 149 § 2, shall issue a decision:

1) refusing to quash the original decision, if the authority finds no grounds for quashing the decision on the basis of Articles 145 § 1, Article 145a or Article 145b; or

2) quashing the original decision, if the authority finds grounds for quashing the decision on the basis of Articles 145 § 1, Article 145a or Article 145b and the authority shall issue a new decision concluding the matter as to the merits.

§ 2. f as a result of reopening the proceedings the original decision may not be quashed due to reasons specified in Article 146, the public administration authority may only rule that the challenged decision was issued in contravention to the law and the authority shall indicate circumstances due to which the authority did not quash the decision.

§ 3. In matters referred to in § 1, the provisions on disposal of the matter without notice by the authority do not apply.

Issue No. 11 “Fulfilling of administrative acts”

Enforceability.

A decision shall not be enforceable before the end of the time limit to file an appeal, unless one of the following exceptional circumstances occurs: (a) the decision has been appended with an immediate enforceability clause (Article 108 of the CAP – e.g. due to particularly significant interests of the parties), or (b) the decision complies with demands of all the parties (Article 130 § 4), or (c) resulting from specific provisions. If an appeal has been filed within the prescribed time limit, enforceability shall be stayed. That means that the decision becomes enforceable on the day it becomes final or if one of the above described circumstances for earlier enforcement has occurred.

Finality.

Decisions which may not be appealed against in the administrative course of instance are final. Each final decision is therefore enforceable. For practical reasons, it is worth noting the fact that the decision becomes final after the time limit to file the appeal ends; the time limit shall be calculated as of the day the decision has been served on the last of the parties participating (identified) in the proceedings. The decision becomes final if none of the parties participating in the proceedings files an appeal within the prescribed time limit.

Those persons who objectively should have had the status of a party but for various reasons have not been identified as parties and considered in the proceedings may attempt to challenge the decision after the end of the prescribed time limit, but only by means of reopening the proceedings.

Appending the document of the decision with a so-called “enforceability clause” is another important issue. This formality is very important for practical reasons, and the CAP does not directly provide for the rules governing the clause. It is a prevailing practice to append the decision with the clause (usually in the form of a stamp) after the lapse of the time limit to file any potential appeals (14 statutory days extended additionally by, depending on the local customs, about 5 days necessary for the letter to reach the addressee) which may be submitted by the parties identified in the proceedings (i.e. those, on whom the decision has been served). Such procedure has not been provided for in the Code, however, it is not defective, and the appropriate legal basis therefore may be found in the provisions of the Code governing the issuance of certificates.

Article 16. [Principle of durability of an administrative decision] § 1. Decisions which are not appealable in the administrative course of instance or which are not subject to review shall be final. Such decisions may be quashed, amended, declared invalid or the proceedings may be reopened only in instances provided for in the Code or separate statutes.

§ 2. Claims may be filed with an administrative court on grounds of violation of law, on terms and according to procedures specified in separate statutes.

§ 3. Final decisions that are not appealable to the court shall be legally binding.

Article 108. [Grounds for immediate enforceability] § 1. A decision which may be appealed against may be appended with an immediate enforceability clause, if it is indispensable to protect human health or life or to protect national assets from severe damage or due to other public interest or especially important interest of a party. In the last case the public administration authority, by means of an order, may request that the party submit appropriate security.

§ 2. The decision may be appended with the immediate enforceability clause also after the decision has been issued. In such case the authority issues an order which shall be subject to a complaint filed by the party.

Article 110. [Consequences of service; decisions given orally] § 1. The public administration authority which issued the decision shall be bound by the decision from the moment the decision was served or communicated orally, unless the Code provides otherwise.

§ 2. In case the matter has been disposed of without notice by the authority, the public administration authority shall be bound by the determination made in such a manner as from the day following the day when the time limit expires for the issuance of a decision or order concluding the proceedings or for filing an opposition, unless the Code provides otherwise.

Article 130. [Effect upon enforceability] § 1. The decision shall not be enforceable before the end of the time limit to submit the appeal.

§ 2. The submission of the appeal shall stay the enforcement of the decision.

§ 3. The provisions of § 1 and § 2 shall not apply if:

1) the decision has been appended with an immediate enforceability clause (Article 108);

2) the decision shall be immediately enforceable by operation of law.

§ 4. The decision is subject to enforcement before the expiry of the time limit for filing an appeal, if it is compliant with the demands of all the parties or if all the parties waived their right of appeal.

Issue No. 12. “Administrative agreement”

The administrative agreement is one of the non-controlling forms of administration. The agreement is a bilateral or multilateral act in the field of administrative law, carried out by entities performing public administration, and coming into effect on the basis of consistent declarations of will of these entities. Agreements are similar to civil law transactions because they are based on the principle of equality of parties. They are concluded between entities not related by organizational or service subordinate ties.

The agreement distinguishes itself from civil law transactions primarily by its object, which lies in the sphere of administrative law, not civil law.

The subject of the agreement are obligations (but not in the civil law sense) regarding the implementation of public administration tasks. Agreements provide for the joint performance of tasks imposed on entities that are parties to the agreement, or the transfer of certain tasks from one entity to another. On the basis of agreements, administrative-legal relations are created, which differ, however, from classical relations. Namely, relations are characterized by equality of parties. Most often, the subject of the agreements is the broadly understood cooperation of various types of public administration units, sometimes also the cooperation of these units with social and cooperative organizations. The agreements, however, are not internal activities of public administration. As a result of the agreement, the tasks of one body may be transferred to another, or the employees of one body may be authorized by the other body to handle administrative matters on its behalf.

The parties to the administrative agreement may be any entities of administrative law, and therefore also entities without legal personality. However, in order to be able to speak of an administrative agreement, at least one of the parties to the agreement should be an entity performing public administration functions.

The institution of the administrative agreement is known to Polish law, however, the provisions allowing or ordering its conclusion are few. It is connected with the lack of specification of the procedure in which a possible dispute between the parties to the agreement can be settled, as well as the lack of clearly defined consequences of failure to meet the obligations entered into in the agreement. An example of the above-mentioned provisions is Art. 74 of the Act of 8 March 1990 on communal self-government (Journal of Laws 2019.506 c.t.) and art. 20 of the Act of 23 January 2009 on the Voivode and Government Administration in the Voivodship (Journal of Laws 2019.1464 c.t.)

Art. 74. [Inter-commune agreements]

1. Communes may conclude inter-commune agreements regarding the entrustment of one of them with public tasks specified by them.

2. The commune performing public tasks covered by the agreement assumes the rights and obligations of other communes related to the tasks entrusted to it, and these communes are required to participate in the costs of implementing the entrusted task.

Art. 20. [Entrusting matters falling within the competence of a voivode]

1. The voivode may entrust the conduct of, on his behalf, certain matters within its jurisdiction to local government units or other self-government bodies operating in the voivodship, heads of state and self-government legal entities and other state organizational units operating in the voivodship.

2. The entrustment takes place on the basis of an agreement between the voivode, respectively, with the executive body of the local self-government unit, the competent body of another local self-government or the head of a state and local self-government legal person or other state organizational unit referred to in sec. 1. The agreement, together with its annexes constituting its integral part, is subject to announcement in the voivodship official journal.

3. In the agreement referred to in sec. 2, rules are laid down for the voivode to exercise control over the proper performance of entrusted tasks.

It should be noted, that, there are no provisions regulating administrative agreement in Polish Administrative Procedure Code, however this code regulates the institution of settlement.

In a matter pending before a public administration authority, parties may reach a settlement if the nature of the matter allows therefor, if it contributes to the acceleration or facilitation of the proceedings, and if it does not violate any provision of the law. The settlement is an agreement made in writing between parties to the administrative proceedings who are in dispute (have opposing interests). Such a settlement is a substitute to an administrative decision in the matter. The fact that the parties reached a settlement is recorded in a protocol. The settlement shall be approved by means of an order within seven days of the day it has been made. Disposal of administrative matters by way of a settlement is very rare and, in practice, are of marginal importance.

Settlement occurring in the provisions of administrative law may have the form of two types: settlement between the authority and the party and settlement between the parties to the proceedings, concluded before the authority. The Code of Administrative Procedure regulates the second form of settlement.

The settlement is not the main form of settling the case, which results from the assumptions of the legal regulations contained in Art. 114-122 of the Code of Administrative Procedure. Pursuant to these provisions, the conditions for concluding a settlement by the parties, which will become a form of settlement, are as follows:

1) the individual case must be pending before a public administration body, because the settlement may only be concluded during the administrative procedure;

2) at least two parties are involved in the case, whose legal interest or duty is of this nature, that they allow negotiations between them and concessions as to the result of the case mentioned in art. 13 § 1 of the CAP referred to as contentious issues;

3) the settlement will not be a circumvention of the specific requirements set for the settlement of the case because of the obligation to cooperate with public administration bodies;

4) settlement is not excluded by separate provisions;

5) the content of the settlement does not violate the requirements of the public interest or the legitimate interest of the parties.

The settlement corresponding to these premises, after its approval by the administrative authority, replaces the decision in the case, because pursuant to Art. 121 of the CAP, the approved settlement has the same effects as the decision issued during the administrative procedure.

Article 114. [Admissibility of a settlement] In a pending matter the parties may reach a settlement, if the nature of the matter so permits and if it is not contrary to any specific provisions.

Article 115. [Deadline to settle] The settlement may be concluded before the public administration authority before which the proceedings in the first instance or appellate proceedings have been pending, until the authority issues a decision in the matter.

Article 116. [Setting the time limits] § 1. The public administration authority shall postpone the issuance of the decision and shall set a time limit for the parties to settle, if grounds exist for the conclusion of such settlement and shall instruct the parties on the manner and effects of the settlement.

§ 2. If one of the parties provides notice that he is no longer willing to reach the settlement or fails to observe the time limit set in accordance with § 1, the public administration authority shall dispose of the matter by way of a decision.

Article 117. [Form and contents] § 1. The settlement shall be prepared by an entitled employee of the public administration authority in writing or in the form of an electronic document in accordance with the joint statement by the parties. In case the settlement is prepared in writing, the statements shall be submitted to the entitled employee of the authority.

§ 1a. Contents of the settlement:

1) the particulars of the public administration authority before which the settlement has been reached and of the parties to the proceedings;

2) the date of the settlement;

3) the subject matter and contents of the settlement; and

4) the signatures of the parties and the signature of the entitled employee of the public administration authority, including the forename and surname and official position, and if the settlement has been concluded in the form of an electronic document – qualified electronic signatures of the parties and of the entitled employee of the public administration authority.

§ 2. Before signing the settlement, the entitled employee of the public administration authority shall read out the contents of the settlement to the parties, unless the settlement has been drawn up in the form of an electronic document. The settlement shall be entered in the records.

Article 118. [Approval] § 1. The settlement shall be approved by the public administration authority before which it had been made.

§ 2. If the settlement concerns a matter which may be disposed of only upon another authority’s having expressed its position, Article 106 applies mutatis mutandis.

§ 3. The public administration authority shall refuse to approve the settlement, if the settlement infringes the law, if it ignores the position of the authority referred to in § 2, or if it infringes on the public interest or just interest of the parties.

Article 119. [Continued] § 1. The approval of or refusal to approve the settlement shall be effected by way of an order which shall be subject to complaint; the order relating to the matter shall be issued within 7 days of the day of the settlement.

§ 2. If the settlement has been made in the course of appellate proceedings, the decision of the first instance authority shall expire on the day the order approving the settlement became final; a relevant instruction informing thereof shall be included in the order.

§ 3. A copy of the settlement shall be delivered to the party together with the order approving the settlement.

Article 120. [Enforceability of the settlement] § 1. The settlement shall be enforceable as of the day the order approving the settlement becomes final.

§ 2. The public administration authority before which the settlement has been made shall confirm the enforceability of the settlement on a copy of the settlement.

Article 121. [Effects] The approved settlement shall have the same effect as the decision issued in the course of the administrative proceedings.

Issue No. 13 “Defining a list of decisions that cannot be appealed in the framework of administrative legal proceedings, for example, political decisions of the President and others”

Article 2 of the Constitution of the Republic of Poland of April 2, 1997 states: "The Republic of Poland is a democratic state ruled by law, implementing the principles of social justice”. From the principle of a democratic rule of law, two further principles are derived, which are of great importance for shaping the rights of individuals against public administration: the principle of the right to a trial and the principle of the right to a court.

Guaranteeing the implementation of the right to court principle in the Polish Constitution, in art. 77 section 2, the right to a court has been expressly established, stating: "The Act may not close anyone's way of claiming infringements of freedoms or rights", and Article 45 sets standards for the right to a court by adopting a solution according to which "Everyone has the right to fair and public hearing cases without undue delay by a competent, independent, impartial and independent court [para. 1]. Disputes may be excluded due to morality, state security and public order and due to the protection of the private lives of the parties or other important private interests. is public [para. 2]. "

The Polish Constitution, specifying the jurisdiction of the Supreme Administrative Court and administrative courts, provides in art. 184: „The Supreme Administrative Court and other administrative courts shall exercise, to the extent specified by statute, control over the performance of public administration. Such control shall also extend to judgments on the conformity to statutes of resolutions of organs of local government and normative acts of territorial organs of government administration."

According to art. 1 § 1 of the Act of 25 July 2002 - Law on the System of Administrative Courts (LSAC): „ Administrative courts shall administer justice through reviewing the activity of public administration and resolving disputes as to competence and jurisdiction between local government authorities, appellate boards of local government, and between these authorities and government administration authorities.”

Based on Article. 184 of the Polish Constitution and Art. 1of the LSAC the subject of administrative court proceedings was specified in the Act of 30 August 2002 - Law on Proceedings Before Administrative Courts (LPBAC). The subject of administrative court proceedings are administrative court cases. According to Art. 1 of the LPBAC: „The law on proceedings before administrative courts shall regulate judicial proceedings in matters relating to review of the activity of public administration and in other matters to which provisions thereof apply by virtue of specific statutes (administrative court cases).” To determine the administrative court case it should be taken into account the legal solutions adopted in Articles 3, 4, 5 and 58 § 1 point 1 of the LPBAC).

The Law of 30th August 2002 on Proceedings Before Administrative Courts:

Art. 3. § 1. Administrative courts shall exercise review of the activity of public administration and employ means specified in statute.

§ 2. The review of the activity of public administration by administrative courts shall include adjudicating on complaints against:

1)administrative decisions;

2) orders made in administrative proceedings, which are subject to interlocutory appeal or those concluding the proceeding, as well as orders resolving the case in its merit;

3) orders made in enforcement proceedings and proceedings to secure claims which are subject to an interlocutory appeal, with the exclusion of the orders of a creditor on the inadmissibility of the allegation made and orders dealing with the position of a creditor on the allegation made;

4) acts or actions related to public administration regarding rights or obligations under legal regulations other than acts or actions specified in points 1–3, excluding acts or activities taken in the course of administrative proceedings specified in the Act of 14th June 1960 – Code of Administrative Proceedings

(Journal of Laws of 2016, item 23, 868, 996, 1579, 2138 and of 2017, item 935), proceedings specified in sections IV, V and VI of the Act of 29th August 1997 – Tax Ordinance (Journal of Laws of 2018, item 800, as amended), proceedings referred to in section V in chapter 1 of the Act of 16th November 2016 on the National Tax Administration (Journal of Laws of 2018, item 508, 650, 723, 1000 and 1039) and proceedings to which the provisions of the quoted acts apply;

4a) written interpretations of tax law issued in individual cases, protective tax opinions and refusal to issue protective tax opinions;

5) local enactments issued by local government authorities and territorial agencies of government administration;

6) enactments issued by units of local government and their associations, other than those specified in subparagraph 5, in respect of matters falling within the scope of public administration;

7) acts of supervision over activities of local government authorities;

8) lack of action or excessive length of proceedings in the cases referred to in subparagraphs 1–4 or excessive length of proceedings in the case referred to in subparagraph 4a;

9) lack of action or excessive length of proceedings in cases relating to acts or actions other than the acts or actions referred to in subparagraphs 1–3, falling within the scope of public administration and relating to the rights or obligations arising from the provisions of law, taken in the course of the administrative proceedings referred to in the Code of administrative proceedings of 14th June 1960 and proceedings referred to in sections IV, V and VI of the Tax Ordinance Act of 29th August 1997 as well as proceedings to which the provisions of the abovementioned Acts apply.

§ 2a. Additionally, administrative courts shall issue rulings in appeals against decisions issued under Article 138(2) of the Act of 14th June 1960 – Code of Administrative Proceedings.

§ 3. Administrative courts shall also adjudicate in respect of matters where provisions of specific statutes provide for judicial review, and shall employ means specified in those provisions.

Art. 4. Administrative courts shall resolve jurisdictional disputes between local government authorities and between self-government appellate boards, unless a separate statute provides otherwise, and shall resolve disputes as to competence between local government authorities and government administration agencies.

Art. 5. Administrative courts shall have no competence in matters:

1) ensuing from organisational superiority or subordination

in relations between public administration authorities;

2) ensuing from official submission of subordinates to superiors;

3) relating to refusal to appoint for an office or to designate to perform a function in public administration authorities, unless such obligation of appointment or designation ensuesfrom the provision of law;

4) relating to visas issued by consuls, except for visas:

(a) referred to in Article 2 points 2 to 5 of Regulation (EC) No 810/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 July 2009 establishing a Community Code on Visas (Visa Code) (OJ L 243, 15.9.2009, p. 1,

as amended),

(b) issued to a foreigner being a family member of a national of the European Union Member State, a family

member of a national of a Member State of the European Free Trade Association (ETFA) – a party to the European Economic Area Agreement or a family member of a national of the Swiss Confederation, within the meaning of Article 2(4) of the Act of 14 July 2006 on the entry into, residence in and exit from the Republic of Poland of nationals of the European Union Member States and their family members (Journal of Laws of 2017, item 900 and of 2018, item 650);

5) relating to local border traffic permits issued by consuls.

Art. 58. § 1. The court shall reject the complaint:

1) if the case does not fall within the jurisdiction of the administrative court;

2) lodged after the expiry of prescribed time limit;

3) when formal deficiencies of the complaint have not been corrected within the prescribed time limit;

4) if the matter subject to the complaint between the same parties is pending or has already been decided by a legally binding decision;

5) if one of the parties has no capacity be a party in court or if the complainant does not have procedural capacity and he/ she has not been substituted by a statutory representative or there are defects in the composition of the bodies of an organisational unit being the complainant which prevent it from operation;

5a) if the legal interest or right of the person lodging a complaint against the resolution or act referred to in art. 3 § 2 subparagraphs 5 and 6 were not breached in the manner provided for in the special provision;

6) if lodging of a complaint is inadmissible for other reasons § 2. For the reason of lack of capacity to be a party in by any of the parties or because of lack of procedural capacity on the part of the complainant, non-existence of a statutory representative or the defects in the composition of the authorities of an organisational units being a complainant which prevent it from operation, the court shall reject the complaint only when the defect has not been corrected.

§ 3. The court shall reject the complaint by an order. The complaint may be rejected in camera.

§ 4. The court may not reject the complaint for a reason referred to in § 1(1), if the common court has found itself to have no jurisdiction in this case.

An administrative court case is an examination and resolution by an administrative court of a complaint about the lawfulness of the action or inaction of bodies performing public administration, with the exception provided for in Art. 5 and art. 58 § 1 item 1 of the LPBA. The constitutive element of the administrative court case is the administrative court's control of public administration activities. This element distinguishes an administrative court case from an administrative case. A characteristic feature of an administrative matter is its substantive settlement by making an authoritative specification of the substantive law norm in terms of the rights or obligations of the individual. The administrative court applies the measures provided for in the Act. However, subject to exceptions, the essence of these measures is only to abolish the act or inaction that is unlawful, and not to make a substantive decision in this respect.

When specifying the subject of administrative court proceedings, a distinction should be made with regard to proceedings before voivodship administrative courts and proceedings before the Supreme Administrative Court. The subject of administrative court proceedings before voivodship administrative courts is the administrative court case, and therefore the examination and resolution of the complaint about the action or inaction of the body executing public administration. In this regard, there is the identity of the subject of the proceedings before the voivodship administrative courts and the Supreme Administrative Court, and the only difference is that the Supreme Administrative Court performs this control indirectly - by examining and resolving the cassation complaint. The subject of proceedings before the Supreme Administrative Court is also the recognition and settlement of disputes over jurisdiction and other matters transferred pursuant to separate laws. The Supreme Administrative Court is competent to conduct ancillary proceedings - proceedings in matters of resolutions aimed at clarifying legal provisions whose application caused discrepancies in the jurisprudence of administrative courts and adopting resolutions containing resolution of legal issues raising serious doubts in a particular administrative court case.

Types of complaints to the administrative court. They are determined by the scope of jurisdiction of administrative courts. Two methods of determining the jurisdiction of administrative courts are used in legislation:

1) a general clause, which consists in the fact that, in principle, all administrative matters belong to administrative courts, unless they are expressly excluded by an express rule of law; the general clause is usually supplemented with the negative enumeration of exceptions;

2) positive enumeration, which consists in the fact that administrative courts' jurisdiction covers only cases subject to this jurisdiction by an explicit legal provision.

Issue No. 14 (а) “The distinction between the APC and the AOC regarding the application of monetary coercion under the APC and the imposition of an administrative penalty in accordance with the AOC for failure to comply with prescriptions and other administrative acts”

First of all, it should be emphasized that there is no Administrative Offenses Code in Poland. There is also no concept of administrative offense or administrative misdemeanor in the Polish legal system. Instead, the term “administrative tort” is used. Administrative tort is understood in the science of administrative law as an entity's activity that violates binding law and is threatened by administrative sanction. In connection with the above, within the meaning of the concept of an administrative tort, the element that is the subject of the entity's activity that violates binding legal norms of an abstract, general or individual and specific nature, e.g. norms resulting from a decision granting specific rights and specifying the obligations contained in an abstract and general norm. The implementation of liability for administrative torts takes place as part of administrative procedure, which are then subject to administrative court review.

The gradual increase in the repressive nature of penal sanctions in administrative law, which goes hand in hand with the inclusion of sometimes very serious violations to administrative torts, causes that the differences between the nature of these violations and the intensity of sanctioning administrative torts and offences or misdemeanors are blurred. Often, both the burden of violations included in the formal classifications as administrative torts, and the severity of the penalties applicable to them are many times higher than in the case of misdemeanors and even offences. First of all, it should be emphasized that one common definition of statutory administrative sanction is missing. By way of example, it can be pointed out that the Polish legislator uses various formulations in various legal acts, which in colloquial language are understood as ailments. Examples of these terms are: sanction fee, administrative monetary penalties, additional amount, increased fee, fines, additional tax liability.

Contrary to criminal law, there is no general regulation in Polish administrative law that regulates, in addition to the legal definition, such matters as: principles of liability for administrative tort, cessation of tort delinquency due to the elapse of time, exclusion of administrative responsibility for actions that exhaust the features of an administrative tort (exonerative circumstances, counter-forms), how to measure the administrative sanction and refrain from imposing such a sanction. The boundary between the administrative tort and the consequent administrative penalty and the misdemeanor is fluid, and its determination depends in many situations from the recognition of the legislative authority.

An issue that raises a lot of controversy both in practice and in the Polish science of administrative law are administrative penalties. It is argued that the sanctions in question should be regarded as a departure from the principle that penalties are imposed by courts in the administration of justice. The purpose of these sanctions, as in criminal law, is repression as well as general and specific prevention. It is argued in the literature that the legal nature of the liability in question is not understood uniformly. It should be noted, however, that this is definitely not criminal liability within the meaning of the Polish Penal Code or the Code of Misdemeanors, but an independent administrative sanction. The sanction falls within the definition of an administrative penalty when it is a pecuniary or non-pecuniary sanction imposed in the form of an administrative act (usually an administrative decision), based on public law provisions for violation of administrative obligations. Some doubts, however, relate to the separation of this type of sanctions from enforcement measures, disciplinary penalties (e.g. imposed for violation of public finance discipline) and order liability, which are also most often considered administrative penalties. Particular differences relate primarily to procedural penalties, because they are intended to force indicated entities to specific behavior during administrative procedure, and may also be imposed repeatedly (the principle of ne bis in idem known in criminal law does not apply). All this means that they resemble execution-type sanctions and are sometimes called execution penalties. Therefore, the characteristic feature of administrative penalties may be the multiplicity and diversity of forms of their occurrence, generally unheard of in other areas of law. In view of the fact that administrative bodies impose typical administrative penalties by way of an administrative decision, the penalized entity is covered by protection measures through procedural guarantees provided for in the Code of Administrative Procedure. In addition, the authority is bound by the decision it has issued, which means that the penalty once imposed cannot be withdrawn.

In 2017, the new Division IXa. Administrative monetary penalties, was added to the Code of Administrative Procedure.

Division IXa. Administrative monetary penalties

Article 189a. [Conflict rules relating to administrative monetary penalties] § 1.The provisions of this division apply to matters where administrative monetary penalties are imposed or enforced, or where relief is granted in the enforcement thereof.

§ 2. In the event separate regulations govern:

1) the grounds for the calculation of an administrative monetary penalty;

2) the waiving of an administrative monetary penalty or the issuing of instruction;

3) limitation periods in relation to the imposition of an administrative monetary penalty;

4) limitation periods in relation to the enforcement of an administrative monetary penalty;

5) default interest on the administrative monetary penalty; or

6) the granting of relief with regard to the enforcement of an administrative monetary penalty

- the provisions of this division do not apply.

§ 3. The provisions of this division do not apply to matters where the public administration authority imposes or enforces sanctions under the provisions relating to proceedings for petty offences, disciplinary liability, liability for failure to obey work rules or infringement upon public finance discipline.

Article 189b. [Concept and legal effects of the administrative monetary penalty] The administrative monetary penalty means a monetary sanction specified by statute and imposed by the public administration authority by way of a decision as a result of an infringement of law consisting in a failure to comply with an obligation or in a breach of a prohibition imposed on a natural person, a legal person or an organisation unit not having the status of a legal person.

Article 189c. [Principle of more favourable provision for the party] If upon issuing a decision with regard to the administrative monetary penalty, a different statute is in force than at the time of infringement for which the sanction is to be imposed, the new statute shall apply, however the old statute shall be applied, if it is more favourable for the party.

Article 189d. [Grounds for the imposition of an administrative monetary penalty] When imposing an administrative monetary penalty the public administration authority shall consider:

1) the gravity and circumstances of the infringement of law, in particular the need to protect the life or heath, large-size property or an essential public interest or a particularly special interest of a party, as well as the duration of such infringement;

2) the frequency with which, in the past, a duty or prohibition was breached of a similar type as the duty or prohibition whose breach gave rise to the imposition of the penalty;

3) sanctions previously imposed for the same conduct, offence, fiscal offence, petty offence or fiscal petty offence;

4) the degree in which the party to be sanctioned with a monetary penalty contributed to the violation of law;

5) actions undertaken by the party on his initiative in order to avoid the effects of violation of law;

6) the amount of gain, which the party achieved or of loss which the party avoided; or

7) in case of a natural person – personal aspects of the party on whom the administrative monetary penalty is to be imposed.

Article 189e. [Force majeure] The party shall not be sanctioned, if the violation of law was caused by force majeure.

Article 189f. [Grounds for waiving the administrative monetary penalty] § 1. By way of a decision, the public administration authority waives the administrative monetary penalty and issues an instruction only, if:

1) the gravity of infringement of the law was insignificant, and the party ceased to infringe the law; or

2)a different competent public administration authority had previously imposed, by way of a decision which became legally binding, a monetary penalty on the party for the same conduct, or a penalty, which became legally binding, was pronounced with respect to the party for a petty offence or fiscal petty offence, or a sentence, which became legally binding, was pronounced with respect to the party for an offence or fiscal offence, provided that the previous sanction allowed to achieve the objectives for which the administrative monetary penalty was to be imposed.

§ 2. In cases other than those referred to in § 1, if the objectives for which the administrative monetary penalty is to be imposed may be attained, the public administration authority may, by way of an order, set a time limit for the presentation of evidence proving that:

1) the infringement of law has ceased; or

2) a notice of the stated infringement of law has been given to relevant entities, specifying the time limit and the manner of notice.

§ 3. In cases referred to in § 2, the public administration authority waives the administrative monetary penalty and issues an instruction only, if the party presented evidence proving that the order has been complied with.

Article 189g. [Prescription of the penalty] § 1. An administrative monetary penalty may not be imposed, if a period of 5 years has elapsed since the infringement of law or occurrence of the effects thereof.

§ 2. The provision of § 1 does not apply to matters for which separate regulations provide for a time limit upon the expiry of which proceedings may not be initiated in relation to the administrative monetary penalty or determination of the infringement of law which could lead to the imposition of the sanction.

§ 3. The administrative monetary penalty is not subject to enforcement after 5 years of the day when the sanction should have been enforced.

Article 189h. [Running of limitation period for the imposition of an administrative monetary penalty] § 1. The limitation period for the imposition of an administrative monetary penalty shall be interrupted upon declaration of bankruptcy of a party.

§ 2. An interrupted limitation period for the imposition of an administrative monetary penalty shall start running anew from the day following the date when the order on the termination or discontinuance of the bankruptcy proceedings became legally binding.

§ 3. If bankruptcy had been declared before the start of

|

|

|

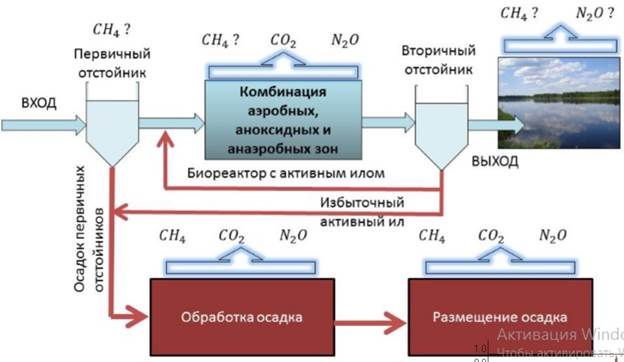

Эмиссия газов от очистных сооружений канализации: В последние годы внимание мирового сообщества сосредоточено на экологических проблемах...

Историки об Елизавете Петровне: Елизавета попала между двумя встречными культурными течениями, воспитывалась среди новых европейских веяний и преданий...

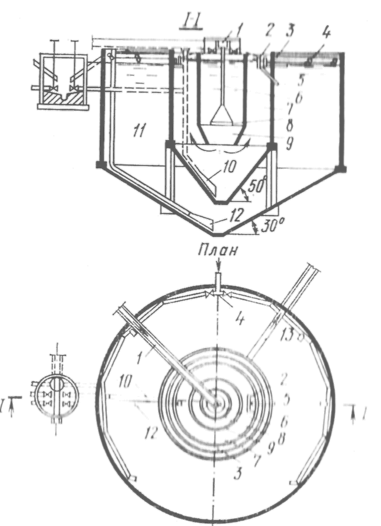

Типы сооружений для обработки осадков: Септиками называются сооружения, в которых одновременно происходят осветление сточной жидкости...

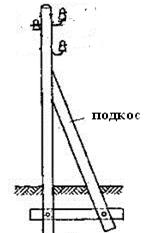

Опора деревянной одностоечной и способы укрепление угловых опор: Опоры ВЛ - конструкции, предназначенные для поддерживания проводов на необходимой высоте над землей, водой...

© cyberpedia.su 2017-2024 - Не является автором материалов. Исключительное право сохранено за автором текста.

Если вы не хотите, чтобы данный материал был у нас на сайте, перейдите по ссылке: Нарушение авторских прав. Мы поможем в написании вашей работы!