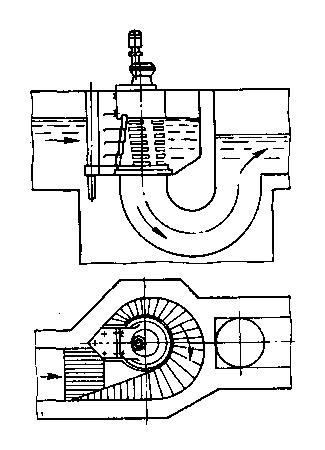

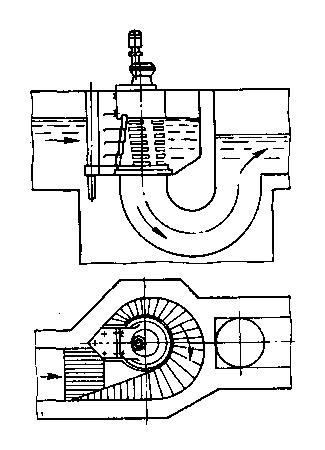

Состав сооружений: решетки и песколовки: Решетки – это первое устройство в схеме очистных сооружений. Они представляют...

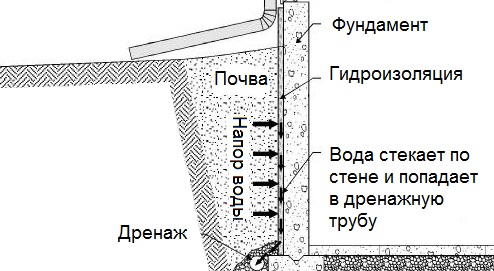

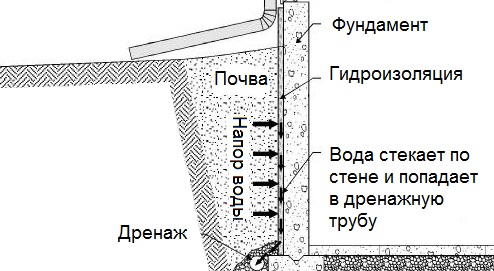

Общие условия выбора системы дренажа: Система дренажа выбирается в зависимости от характера защищаемого...

Состав сооружений: решетки и песколовки: Решетки – это первое устройство в схеме очистных сооружений. Они представляют...

Общие условия выбора системы дренажа: Система дренажа выбирается в зависимости от характера защищаемого...

Топ:

Отражение на счетах бухгалтерского учета процесса приобретения: Процесс заготовления представляет систему экономических событий, включающих приобретение организацией у поставщиков сырья...

Определение места расположения распределительного центра: Фирма реализует продукцию на рынках сбыта и имеет постоянных поставщиков в разных регионах. Увеличение объема продаж...

Интересное:

Средства для ингаляционного наркоза: Наркоз наступает в результате вдыхания (ингаляции) средств, которое осуществляют или с помощью маски...

Искусственное повышение поверхности территории: Варианты искусственного повышения поверхности территории необходимо выбирать на основе анализа следующих характеристик защищаемой территории...

Что нужно делать при лейкемии: Прежде всего, необходимо выяснить, не страдаете ли вы каким-либо душевным недугом...

Дисциплины:

|

из

5.00

|

Заказать работу |

|

|

|

|

R. Mendelsohn,

University of Cape Town

The presence of significant numbers of Russian Jews in South Africa during the Anglo-Boer war (1899-1902), mainly as civilians though some as combatants, has been previously noted by scholars including Apollon Davidson and Irina Filatova in their fine The Russians and the Anglo Boer War.[214] My current research project encompasses these and other Jews who were present during the war. It covers the participation of some 3000 Jews, mainly English but also on occasion of Russian origin, in the British forces. These chose to demonstrate their patriotism at time when Anglo-Jewry was under public pressure as a result of a flood of immigrants arriving in England from the Russian empire.[215] It also covers the more limited participation of Jews in the Boer forces, perhaps a few of hundred at most. (By and large Jewish residents of the Boer republics were recent arrivals who understandably did not see the war as their war.) Finally, the study considers the experience of the some ten thousand Jewish civilians who lived in Kruger’s South African Republic and its neighbour, the Orange Free State, at the outbreak of the war. Many of these joined the general Uitlander exodus from the cities of interior, Johannesburg and Pretoria, for the relative security of the coast but some remained for a part or the whole of the war.

The Jewish population of the Boer Republics was heterogeneous in character. Significant numbers had come from western and central Europe. These were highly acculturated and largely indistinguishable from fellow British, Germans and Hollanders. Much larger numbers had come from Eastern Europe, chiefly from the Russian Empire, and predominantly from one limited geographical area, the Kovno and Suvalki provinces in Lithuania, though there were also small numbers from Latvia and Poland. These Jews were by and large recent departures, part of the wave of Jewish migration from the Tsarist empire in the last decades of the nineteenth and early decades of the twentieth centuries. (There were some earlier Eastern European Jewish arrivals in South Africa prior to the 1880s. I have written a biography of one of these, Sammy Marks who left Russia as youngster of seventeen for England in 1861 before coming on to South Africa in 1868 where he made successive fortunes on the Kimberley diamond fields in 1870s and in the Transvaal from coal mining and secondary industry in the 1880s and 1890s.)[216]

While Marks and others arrived in the 1860s and 1870s, the major influx began in the 1880s in the wake of the pogroms and so-called May Laws following the assassination of Tsar Alexander II in 1881. Those who chose to come south rather than heading westwards across the Atlantic were drawn by the discovery of gold on the Witwatersrand in 1886, the largest worldwide discovery of gold hitherto. Some of new arrival settled in the coastal ports of the British colonies of Natal and the Cape, but the majority of these new immigrants moved into the interior, to the Boer republics, particularly Paul Kruger’s South African Republic.

|

|

My current study is attempting to capture the experience of this population through the war. As a part of this I need to develop a sense of the character of this population on the eve of the war, and also need to see how this population emerged from the war. My initial source for this was the contemporary Jewish press, in particular the detailed reporting of the war in the London Jewish Chronicle, the weekly voice of British Jewry, and in its English rival, the Jewish World. Though most of their attention focused on the patriotism and heroic deeds of the Anglo-Jewish soldiery, some attention was paid to the fate of Jews in the republics. My major discovery, a stroke of good fortune, was the discovery in the State Archives in Pretoria of the papers of the Central Judicial Commission, a body set up by the British after their victory in the war to investigate and adjudicate claims for compensation for damage to property incurred during the war.

The background to the creation of the Commission is the extensive damage to the property of burghers and of foreign subjects living in Transvaal and Free State due to the devastating nature of the war. This was particularly the case in the countryside where successive British commanders-in-chief, Lord Roberts and Lord Kitchener, adopted punitive scorched earth methods in an effort to end the fierce and sustained resistance of the Boer guerrillas. When the war eventually ended, the British undertook, as part of a programme of pacification and reconstruction of the defeated Republics, to pay compensation for these wartime losses. Very large sums of money were set aside for these purposes. The Central Judicial Commission played a critical role in administering the payments. Claims for compensation were submitted or passed on to this commission. These claims were carefully investigated, often by magistrates and the police. The Commission would then rule on the merits of the claim and make awards.

The Archives of the Central Judicial Commission are organised by category: British Subjects, Burghers, Protected Burghers, Foreign Subjects, and within the latter, by country of origin, French, German, American, Dutch, Turkish, and so on. One of the largest sub-categories is the Russian section: there are some 553 files devoted to claims by Russian subjects and many of these files are quite voluminous. The great majority of the applicants in the Russian section are Jewish rather than ethnic Russians.[217]

What do these voluminous files reveal? Firstly, they provide biographical information about these immigrants, including:

- their years of departure from Russia and of arrival in South Africa

- their ages and marital status

- their occupations

- their patterns of settlement in the republics.

This is rich documentation of a sort not otherwise available for this particular immigrant population.

From these records it is apparent that most had arrived in the 1890s, particularly in the mid-decade, though some had left Russia considerably earlier. Most had come directly from Russia, presumably first travelling to the Baltic ports and then on to England before embarking at Southampton for the long sea journey to Cape Town. But there were cases of stage migration, Jews who had come on to South Africa after extended stays in Britain. With regard to age and marital status, I had expected to find that the great majority of the recent arrivals were young and single men. Instead I found that while these predominated there were a very significant number of older men and a fair number of women. Some of the older men were married but at this early stage of settlement were still unaccompanied by their wives.

|

|

With regard to occupations, an overwhelming number of the applicants described themselves as general dealers and storekeepers. There were also a significant number of hotel keepers and a sprinkling of artisan and miscellaneous occupations: cab drivers, dairymen, butchers, tailors, photographers, hawkers, booksellers, builders, a blacksmith, a printer, a hairdresser, and a handful of farmers. Judging by the extent of the claims for compensation they submitted, many of these had prospered quickly in their new countries. Some had only arrived in the mid-nineties and yet within a few years had accumulated substantial means. (This rapid economic betterment is clearly related to the opportunities a rapidly developing Transvaal offered.)

Regarding patterns of settlement, most of the claims came from urban centers, the Witwatersrand in particular, but also from Pretoria.

There were also many claims from the countryside. The files provide evidence of a pattern of dispersion throughout the backveld. There was a whole constellation of rural stores established and operated by Jews on farms owned by Boers, along the roads of the republic. These Jewish-owned stores supplied local farming communities with goods, and bought and then sent to market their produce. The Archives of the Central Judicial Commission include detailed inventories of products bought from the farmer, mealies (maize), tobacco, skins, wool, and so on. From these records it is clear that Jewish storekeepers played a vital role in the commercialisation of the South African countryside during the last decades of the century.

Besides profiling these Russian Jewish immigrants at the outbreak of the war, the archives of the Central Judicial Commission also richly document the wartime experience of these Jews. The files record the departure of many as refugees on the eve of the war: they detail the crippling losses many suffered as they abandoned their property.

These refugees would board up their homes and stores with wooden planks and corrugated iron, or take their stock of goods to central stores for safekeeping. Much of this property was poorly secured and duly fell victim to waves of looting along the wartime Witwatersrand. (In some cases this was ‘manufactured’ looting as the basis for fraudulent purposes.)

The files also document their lives as refugees, telling us about their wartime destinations and occupations. While it seems that most stuck it out in the Cape Colony, particularly in Cape Town, some of the Russian Jewish refugees returned to Europe, either to Britain or to Russia itself.

Those who remained at the Cape struggled to find employment; many, it seems, were unemployed for the duration and lived off the charity of others. The files also document their often frustrated attempts to return to the Transvaal late in the war or soon afterwards. The British authorities were, it appears, none too eager to have major influx of Jews, some of whom had been involved before the war in undesirable practices such as illicit liquor dealing and prostitution.[218]

The files richly document the experience of the minority who had remained behind, both in the towns and in the countryside. They are particularly revealing of the fate of the latter. Pressure was brought to bear on those who stayed behind to join the commandos going off to fight against the British. A few did so but most resisted service in what was not their war. The key to avoiding commando service were documents issued by M. Aubert, the French Vice-Consul in the Transvaal, acting for the Russian Consul at the start of the war. On the basis of statements from four witnesses the French Vice-Consul issued consular passports stating that the holders were Russian subjects. Armed with these documents asserting that they were foreign subjects the bearers were able to resist efforts to conscript them into the Boer forces.

|

|

These consular documents provided no protection though for their goods and these were commandeered where required by the Boer forces. Many of those who remained behind were involved in supplying the Boer forces, including those laying siege to Mafeking. (The irony here is that the British forces inside Mafeking were able to resist because of the extensive stores laid in by Julius Weil, an Anglo-Jewish merchant with Russian Jewish connections.)

Once the British forces advanced in 1900 and occupied the Boer capitals, ending the conventional phase of the war, Jews like many other residents of the Transvaal and Free State, took an oath of neutrality. Most of the rural Jews were allowed to remain at their stores in the countryside once they had taken the oath. The rapid conclusion to the war the British had expected once the Boer capitals were occupied soon failed to materialise and instead the Boers turn in the second half of 1900 to guerrilla war. Jews were caught in the middle as the Central Judicial Commission archives fully document. Willingly in some cases, unwillingly in others, these Jewish rural storekeepers played an important role in sustaining and encouraging the guerrilla struggle in its initial stages. Jewish stores effectively became supply depots for the commandos. Commandos regularly turned up at these stores and took what they needed: boots, clothing, food, fodder for their horses. The hapless storekeepers had little choice faced by these armed (and dangerous) men.

Collaboration was quite willing though in some cases. There is plentiful evidence in these archives of illicit ‘trading with the enemy’ as the British investigators put it. It seems that the Jewish storekeepers were a vital part of an informal economy that sprang up during the guerrilla phase of the war, with sales of produce to the storekeepers from farms whose owners were on commando, an underground economy that helped to keep the Boer guerrillas in the field.

Given this, as well as their own uncertain loyalties, it is not surprising that the Jewish storekeepers became objects of suspicion, and that in an atmosphere of paranoia and of denunciation many fell victim to accusations, often malicious, of disloyalty. The archives contain records of arrests, often repeated arrests, on the basis of reports from informers.

Given too the willing participation of some and unwilling participation of others in sustaining the commandos, it is equally unsurprising that Jewish storekeepers, become the targets, together with Boer families and black peasants, of the land clearances conducted by the British forces in the second half of 1900 and the first half of 1901. Jewish storekeepers were victims of the scorched earth tactics adopted by Lord Kitchener to deny the commandos any traction in the countryside. The archives are filled with reports of the destruction of Jewish homes and stores in the countryside: poignant tales of the arrival of British columns at remote sites, the issuing of instructions to accompany the columns to town immediately, the hasty packing of a small part of the family’s possessions, the seizure of some of the goods by the British, and the destruction of the rest, together with the burning and dynamiting of the homes and stores.[219]

Take the the unfortunate case of Joseph Aaron Braude for example.[220] Born in the Kovno province in 1854, he had left Russia and come to South Africa in 1887, a year after the discovery of the Witwatersrand. With his wife Bertha he raised a family of six children and prospered as hotel and storekeeper on a farm in the Lichtenberg district of the western Transvaal on the road between Klerksdorp and Vryburg, trading in skins and wool, and earning the respect of their Boer neighbours. “Everyone has a good word for these people and they certainly are a good class of Russian Jew.”, a British office reported to the compensation commission after the war.

|

|

During the early part of the war Braude had goods commandeered by Boers. Later, after the British arrived in May 1900, goods to the value of close to 3000 pounds, a very large sum, were requisitioned by passing British columns. These were fraught and lonely times with the “enemy always hovering about in the neighbourhood”. Neither the Braudes nor their servants could leave the farms, and little news reached them of the progress of the war. The Braudes lived on in this precarious fashion for over a year, till mid 1901, all the while, they would later claim, behaving with scrupulous neutrality.

Nemesis arrived at 8 am on the 31 July 1901 in the shape of a Lieutenant Boyle of the British army who ordered Braude (as Braude testified a few months later) “to pack up whatever personal effects he considered most urgent for himself and his family…and … hold themselves ready to leave at once….” Boyle offered two military mule wagons to carry the Braude family’s possessions. While the family hastily packed, the troops began destroying their furniture and preparing to dynamite and set their buildings on fire. The mule wagons had gone no more than 150 yards, Braude later recalled, when smoke began to pour from his store; looking back from further down the road, he saw the rest of what he had built up over the past eleven years going up in flames. The column marched off with Braude’s mares and donkeys, the troops laden with Braude’s geese, fowl and turkeys. The family were taken by the British troops to Taungs in Bechuanaland, and then “allowed” to proceed to Cape Town at their own expense. Soon afterwards, Braude returned to Russia and had his lapsed Russian nationality re-instated.

In applying for compensation to Britain as a Russian subject, Braude claimed that the fair value for the destroyed buildings and their contents was the very substantial sum of 7068 pounds, an amount disputed by the British, who claimed that Braude was “grossly” exaggerating the value of his losses. Doubt was also cast on his neutrality, and it was alleged that he had kept his store open and traded with the Boer commandos till his removal in July 1901. Deeply despondent, Braude, a ruined man, took his own life in May 1902, leaving his widow and 6 children, “in much straitened circumstances”.[221]

While the archives richly detail the fate of Joseph Braude and his fellow Russian Jews during and immediately after the war, they also graphically reveal the fate of their applications for compensation for their wartime losses. Over 550 applications were made to the Central Judicial Commission by people claiming Russian nationality. Some of these were for relatively small amounts, a matter of just a few pounds, some, as we have seen in the case of the benighted Braude family, were for sizeable amounts. The British conducted careful investigations of many of these claims, seemingly in an effort to minimise them or even invalidate them. They sought to cut down the value of the claims and where possible, to invalidate them on the grounds that the claimants had breeched their neutrality as foreign subjects and had aided the Boers. Hence the importance attached to investigating the commercial activities of these Jewish storekeepers during the war. Many of them were accused of trading with the enemy and had their claims disallowed on these grounds. All these efforts at invalidating the claims on an individual, case by case basis were overtaken by the fortuitous discovery of a means of collective disqualification of the Russian Jewish claims.

The great majority of these Jewish applicants had left Russia without Russian passports, possibly to avoid any risk of conscription. At best a few had internal travel documents. The British discovered that Russian law required that “no Russian leaving his country, legally or properly …be without an Imperial Russian passport”. The passport, “a small Green Book” with the signature of the passport holder on the first page and information in Russian, German and French inside, stipulated that if the holder of the passport was “to retain his Russian Nationality” after five years abroad, he would have to have “his passport extended by the Governor of the province” in which he had obtained the passport.[222]

The Jewish applicants for compensation had no such passport and in most cases, little intention of ever returning to Russia. The only official proof they had of their status as Russian subjects were documents issued by the French consuls in the South African Republic and the Orange Free State acting for the Russian consuls. These were so-called consular passports, issued mainly at the beginning of the war, asserting on the basis of the “testimony of four witnesses” that the individual concerned was a Russian subject. These document was required if the applicants were to remain in the republics and avoid conscription into the Boer commandos.

|

|

The British established to their own obvious satisfaction (and relief) that these documents carried very little legal weight for purposes of claims of nationality. The consular passport was strictly a “temporary” arrangement “to enable a Russian subject to comply with the passport regulations, and obtain the extension of his passport from the Governor of the province.” Failure to comply with these passport regulations meant that one “was debarred from the rights of a Russian subject abroad.”

Like nearly all his fellow Russian Jewish applicants, Moses Aaron, the subject of the test case, a Johannesburg storekeeper who had left Russia in 1863, could produce no Imperial Russian Passport and could provide no evidence that he had ever had such a passport or had ever applied to the Governor of his former province for the extension of such a passport. He was consequently in effect stateless–without a Russian or any other nationality–at the time he had incurred his wartime losses. In the words of British officialdom: “This man, therefore… is not considered to have proved his nationality, or his neutral foreign nationality. In the absence of such proof there will be no award.” Effectively, no proven nationality, no status as a foreign subject, no award.

The precedent established in this case, the Aarons precedent, was then applied across the board to the great majority of the hundreds of Russian Jewish applicants for compensation for wartime losses. Their applications were simply disqualified whatever the merits or otherwise of their actual claims. The notations on the files read:

“not genuine foreign subject”

“not bona fide Russian”

“no nationality”

“No award’”

The only positive outcome of this bureaucratic exercise in futility is precisely the mountain of paperwork it generated, an invaluable historical resource for the recovery of the experience of the infant South African Jewish community at a time of great crisis. A rare and invaluable archival resources for the early history of this particular community, which uniquely allows one to capture both the experience of otherwise obscure individuals and their voices. The voices of victims of great historical forces beyond their control, attempting unsuccessfully to re-establish lives disrupted by a war that was to reshape the whole of South Africa.

|

|

|

Археология об основании Рима: Новые раскопки проясняют и такой острый дискуссионный вопрос, как дата самого возникновения Рима...

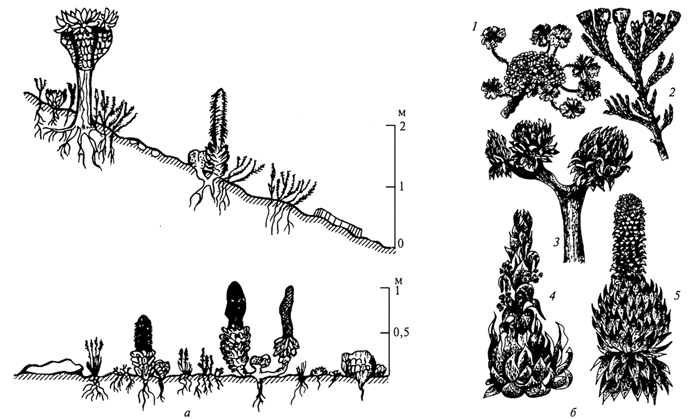

Адаптации растений и животных к жизни в горах: Большое значение для жизни организмов в горах имеют степень расчленения, крутизна и экспозиционные различия склонов...

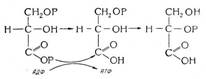

Биохимия спиртового брожения: Основу технологии получения пива составляет спиртовое брожение, - при котором сахар превращается...

Своеобразие русской архитектуры: Основной материал – дерево – быстрота постройки, но недолговечность и необходимость деления...

© cyberpedia.su 2017-2024 - Не является автором материалов. Исключительное право сохранено за автором текста.

Если вы не хотите, чтобы данный материал был у нас на сайте, перейдите по ссылке: Нарушение авторских прав. Мы поможем в написании вашей работы!