Легко читаем по-английски –

«Робинзон Крузо. Robinson Crusoe»: АСТ; Москва; 2015

ISBN 978‑5‑17‑085639‑8

Аннотация

Книга содержит сокращенный и упрощенный текст приключенческого романа Даниэля Дэфо, повествующего о жизни и удивительных приключениях уроженца Йорка Робинзона Крузо. Текст произведения сопровождается упражнениями на понимание прочитанного, постраничными комментариями и словарем, облегчающим чтение.

Предназначается для продолжающих изучать английский язык нижней ступени (уровень 2 – Pre‑Intermediate).

Даниэль Дэфо / Daniel Defoe

Робинзон Крузо / Robinson Crusoe

Адаптация текста, упражнения, комментарии и словарь Н. Д. Анашиной

© Н. Д. Анашина, адаптация текста, упражнения, комментарии, словарь

Chapter 1

Start in Life

I was born in the year 1632, in the city of York. That was my mother’s hometown, because she also was born there, in a family of Robinson’s. They were very old and gentle family of York’s faubourg,[1] from whom I was called Robinson. My father, bored the name Kreutznaer, was German from Bremen. He earned his bread [2] by trading, and, when his case went to the mountain,[3] he moved to England, York. There he met my mother and later they got married. Eventually, the surname Kreutznaer grown into the Crusoe, by the usual corruption of words in England. Therefore, everyone calls me Robinson Crusoe.

I had two elder brothers. One of them went to the army, despite of my father’s prohibitions, and was killed at the battle near Dunkirk. What became of the second brother we never knew, he was missing.

From my childhood I dreamed about the adventures and pirates. I would be satisfied with nothing but going to sea.

Being the third son of my family, I wasn’t high‑educated person. My father had given me house‑education and country free school that was enough to be a lawyer. [4]

When I grow up, my childish dreams of the sea turned into the real wish of becoming a captain, or a sailor at least. Oh, how the sea haunted my dreams that days!

My father, being a wise and grave man, guessed my intentions. [5] One morning he called me into his chamber. He asked me very warmly not to left father’s home and not to repeat the fate of my elder brothers in a search of adventures. “You don’t have to earn your bread”, he said, “I’ll give you enough money to stay at your native country, become a lawyer, and get marriage. You are only eighteen, and I don’t want to lose my third son, when he is so young”. But I didn’t listen to him. He promised me a life of ease and pleasure, but I was going to a life of risky adventures and trying the fortune.

However, I was sincerely [6] affected with my father’s discourse, and decided to wait with the final decision of my future life. I resolved not to think of going abroad one year more, but to settle at home, according to my father’s desire. That was a time, when I was trying myself in the different fields of learning, trying to find a profession that would be close to me. But my searches had been unsuccessful. It turned out, that I had no abilities to any crafts. [7] After that, I had finally decided to link my future life with [8] the sea. However, I could not left my parent’s home without their approval. [9]

One day, when my mother was in a good mood, I asked her for the help.

“Oh, mom, I’ll soon be nineteen years old, and it is too late to become a lawyer or clerk, I have no abilities to any crafts. I see no ways to make living, but go to sea. Please, speak to my father to let me go abroad and become a mariner!”

This put my mother into a great passion. [10] She wondered how I could think in this way after the discourse I had had with my father, and such a kind and tender expression as she knew my father had used to me.

“Neither I, nor your father will bless you. If you don’t obey our advice, we will not take part in your future” – she said.

But for that moment, my decision was enough strong, and adrift, my wishes turned into the real life.

Being one day at Hull, where I went casually, I met one of my companions. He was about to sail to London in his father’s ship. He prompted me to go with him, promising that it should cast me nothing for my passage. [11] I consulted neither father nor mother about this voyage, even nor so much, as sent them a letter of it.

In an ill hour,[12] God knows, on the 1st of September 1651, I went on board a ship bound for London.

The ship was no sooner out of the Humber than the wind began to blow and the sea to rise. I had never been at sea before, so it seemed to me, that the ship was caught in a heavy storm and will drown in a minute. The pitching [13] was so strong, that I could barely stand on my feet, the nausea stepped up to the throat. [14] I thought, that were the last minutes of my life. And only then I realized what I’ve done: all the good counsels of my parents, my father’s tears and my mother’s entreaties,[15] came fresh into my mind.

I swore to myself that if I could stay alive, I’ll come back to my parents in repentance [16] and spend all the entire life near parents in my family home. At that moment in my mind has already appeared the picture from the biblical story “Return of the prodigal son”. [17]

These wise and sober [18] thoughts continued all the while the storm lasted, and indeed some time after; but the next day the wind was abated, and the sea calmer. However, I was very grave for all that day, being also a little sea‑sick still; but towards night the weather cleared up, the wind was quite over, and a charming fine evening followed. The sun went down perfectly clear, and rose so next morning; and having little or no wind, and a smooth sea, the sun shining upon it, the sight was, as I thought, the most delightful that ever I saw.

I had slept well in the night, and was now no more sea‑sick, but very cheerful, looking with wonder upon the sea that was so rough and terrible the day before, and could be so calm and so pleasant in so little a time after. And now, lest my good resolutions should continue, my companion comes to me: “Well, Rob,” says he, clapping me upon the shoulder,[19] “how do you do after it? Were you freighted, last night, when it blew a capful of wind?” “A capful do you call it?” said I, “That was a terrible storm!” “A storm?!” replied he, “do you call that a storm? Why? It was nothing at all; give us a good ship and sea‑room,[20] and we think nothing of such a squall of wind as that; but you are a fresh‑water sailor, Rob. Come, let us make a bowl of punch, and we’ll forget all that! Do you see what charming weather it is now?”

To make short this sad part of my story, we went the way of all sailors; the punch was made and I was made half drunk with it: and in that one night’s wickedness I drowned all my repentance, all my reflections upon my past conduct, all my resolutions for the future.

The sixth day of our being at sea we came into Yarmouth Roads. These Roads are the common harbor, where the ships might wait the tailwind. [21] Here we came to an anchor [22] for seven or eight days. During this time many ships from Newcastle came into the same Roads.

But the wind blew to fresh, and after we had lain four or five days, blew very hard. However, the crew of our ship was absolutely calm: the Yarmouth Roads are known as the safest place; there is no more danger there, than in any other harbor. Moreover, our ship had the good anchor, and our ground‑tackle [23] very strong. So, our men spent all the time in rest and mirth, after the manner of the sea.

But the eight day, in the morning, the wind increased, and we had all hands at work to strike our topmasts,[24] and make everything close, that the ship might ride as easy as possible.

By noon the sea went very high. Once or twice we thought, that our anchor had come home; upon which our master ordered out the sheet‑anchor,[25] so that we rode with two anchors ahead.

By this time it blew a terrible storm indeed. Anyone may judge, what a condition I must been in at all this, who was such a young sailor, and was so frightened in a first little storm. But not the fear of death scared me. It seemed like a Providence punishment. [26] I had broken my oath, which I gave during the first storm. Now it seemed clear, what fate awaits me, if I don’t return home. And these, added to the terror of the storm, put me into such a condition, that I have no words to describe it.

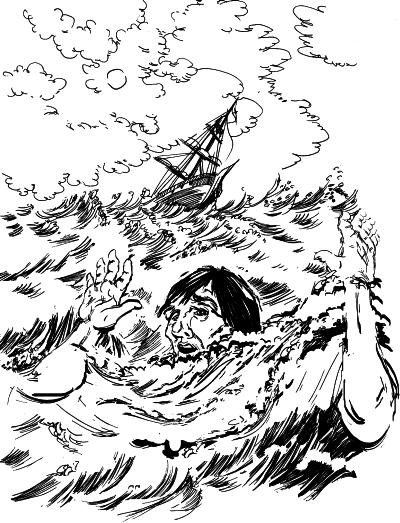

During the first hurries I was stupid, lying still in my cabin, but in the next time I heard as the master went in and out of his cabin by me, saying softly several times a minute “ Lord, be merciful to us! [27] We shall be all lost! We shall be all undone!” and the like. I got up out of my cabin and looked out; but such a dismal sight I never saw. I saw terror and amazement in the faces even of the seamen themselves. The sea ran mountains high, and broke upon us every three or four minutes.

Towards evening the mate and boatswain [28] asked the master of our ship to let them cut away the fore‑mast. [29] When they had cut it away, the main mast [30] shook the ship so much, that they were obliged to cut that away also, and make a clear deck.

Two more ships, that were standing near us, drived from their anchors [31] and were run out of the Roads to sea, at all adventures, without any masts. The similar fate awaited for us. The boatswain, the master, and some others more sensible than the rest were praying, expecting every moment when the ship would go to the bottom.

In the middle of the night we found out the leak in a hold. [32] One of the men that had been down to see cried out, that there was four feet water in the hold. Then all hands were called to the pump. We worked all night long, but the water kept coming. It was clear, that the ship would founder; and though the storm began to fall off a little, but it was impossible to keep afloat till we might run into any port. So the master began firing guns for help. [33]

The light ship, who had rid it out just ahead of us, sent a boat to help us. But it was impossible for us to get on board, or for the boat to lie near the ship’s side. All the men in the boat were rowing very heartily, and venturing their lives [34] to save ours. Finally, we extended them a rope [35] so they managed to swim very close to the board of our ship, and we got all into their boat. It was no purpose for them or us, after we were in the boat, to think of reaching their own ship; so all agreed to let the boat drive on it’s own, and only to pull it in towards shore as much as we could.

We were not much more than a quarter of an hour out of our ship, till we saw its sink. [36] Only then I understood for the first time what was meant by a ship foundering in the sea.

When our boat was mounting the waves, we were able to see the shore. A huge number of people gathered on the beach to help us as soon as we moored to the bank. [37] But we made a very slow way towards the shore. Only when we past the lighthouse [38] at Winterton, we found ourselves in a small bay near the Cromer, where the wind was a little quieter. Here we got in, and though not without much difficulty, got all safe on shore, and walked afterwards on foot to Yarmouth.

As unfortunate men been in the shipwreck,[39] we were used with great humanity there. The townspeople gave us houses to leave, and by the particular merchants and owners of ships we had enough money to carry either to London or back to Hull as we wanted.

My comrade, who was the master’s son, and who prompted me to go with him on his father’s ship to London, was now less forward then I. At Yarmouth we were separated in the town to several quarters, so the first time he spoke to me after the shipwreck was not till two or three days, of our staying in town. He asked me how I did, looking very melancholy and shaking his head. [40] He told his father who I was, and how I had come to this voyage only for a trial, in order to go further abroad.

His father turned to me with a very grave and concerned tone: “Young man,” said he, “you ought never to go to sea anymore; you ought to take this for a plain and visible token that you are not to be a seafaring man.”

“Why, sir,” said I, “will you go to sea no more?”

“That is another case,” said he; “it is my calling, and therefore my duty; but as you made this voyage on trial, you see what a taste Heaven [41] has given”, continues he, “what are you; and on what account did you go to sea?” Upon that I told him some of my story; at the end of which he burst out into a strange kind of passion:[42] “What had I done,” said he, “that such an unhappy wretch should come into my ship? I would not set my foot in the same ship even for a thousand pounds!”

I saw him later, and he repeated his words: “Young man, if you don’t go back, wherever you go, you will meet with nothing, but disasters and disappointments, till your father’s words are fulfilled upon you”.

I saw him no more. Which way he went I knew not.

From Yarmouth I went to London with my own, by land. I had enough money in my pocket for this way. As well as on the road, I had many struggles with myself, what course of life I should take, and whether I should go home or to sea. The first reason, that I didn’t want to return home, was the fear to be laughed at among the neighbours,[43] and should be ashamed to see not my father and mother only, but even everybody else.

Time went on, and the remembrance of the distress I had been in wore off, and I began looking out for a new voyage. Just in those days there was a great opportunity to go to the new voyage aboard the ship, bound to the west coast of Africa, as our sailors vulgarly called it, a voyage to Guinea.

It was a big success for me first of all to fall into pretty good company in London. In the port I met the master of a ship who had already been on the cost of Guinea, and we become friends. His first trip to the west coast of Africa was very successful, so he resolved to go again. Without false modesty [44] I can say that I am a pleasant companion, therefore this captain was taking a fancy to my conversation. Hearing me say I had a mind to see the world, he told me if I would go the voyage with him I should be at no expense, and if I could carry anything with me to sale, I should have all the advantage of it that the trade would admit.

I had enough money in my pocket and good clothes upon my back, so I went to that voyage not as a sailor, but as a simple passenger. I would always go on board in the habit of a gentlemen and so I neither had any business in the ship, nor learned to do any. I might indeed have worked a little harder than ordinary, yet at the same I should have learnt the duty and office of a fore‑mast man,[45] and in time might have qualified myself for a mate of lieutenant, if not for a master. But as it was always my fate to choose for the worse, so I did here.

I decided to follow the advice of the captain, to carry something for trading with me to Guinea, so I asked my relations, whom I corresponded with, for some money. They sent to me 40 pounds, and I carried a small adventure with me, which, by the disinterested honesty of my friend the captain, I increased very considerably;[46] for I carried all my money in such toys and trifles [47] as the captain directed me to buy.

This was the only voyage which I may say was successful in all my adventures, which I owe to the honesty of my friend the captain; under whom also I got a competent knowledge of the mathematics and the rules of navigation, learned how to keep an account of the ship’s course,[48] take an observation, and, in short, to understand some things that were needful to be understood by a sailor; for, as he took delight to instruct me, I took delight to learn; and, in a word, this voyage made me both a sailor and a merchant.

Our trading in Guinea was upon the coast line. I had my misfortunes even in this voyage. I was continually sick, being thrown into a violet calenture [49] by the excessive heat of the climate.

Chapter II

Slavery and Escape

Recovering, I went to London with all the crew and our master. This voyage was very successful to us, all the crew members returned home grown rich. Even my 40 pounds turned into 300 pounds sterling. This first success elated me and I resolved to go to the same voyage again. However, one event overshadowed [50] those days: to my great misfortune, my friend, the master of our ship, was dying soon after the arrival, though I was deprived of the faithful and honest comrade.

When I decided for the second time to set the sail, I found the widow of my deceased friend, captain, and left her 200 pounds for safekeeping, and I must say, she preserved this money very faithfully. So, I did not carry quite 100 pounds of my new‑gained wealth with me to the new voyage.

That was the unhappiest trip that ever man made. Our ship, making her course towards the Canary Islands, or rather between those islands and the African shore, was surprised in the grey of the morning by a Turkish rover [51] of Sallee, who gave chase to us with all the sail he could make. We crowded also as much canvas as our yards would spread,[52] or our masts carry, to get clear; but finding the pirate gained upon us, and would certainly come up with us in a few hours, we prepared to fight; our ship having twelve guns, and the rogue eighteen. About three in the afternoon he came up with us [53] and entered sixty men upon our decks, who immediately fell to cutting and hacking the sails and rigging. [54] We plied them with small shot, half‑pikes, powder‑chests, and such like, and cleared our deck of them twice. However, to cut short this melancholy part of our story, our ship was disabled, and three of our men killed, and eight wounded, we were obliged to yield,[55] and were carried all prisoners into Sallee, a port belonging to the Moors.

Most of our men were carried up the country to the emperor’s court or to the slave market. However, in those days I was young, strong, nimble [56] and smart fellow, so my fate was not as abysmal as the rest crew: I was kept by the captain of the rover as his proper prize, and made his own slave. At this surprising change of my fate, from a merchant to a miserable slave, I was perfectly overwhelmed;[57] and now I looked back upon my father’s prophetic [58] discourse to me, that I should be miserable and have none to relieve me.

My new patron, or master, had taken me to his house, so I was in hopes that he would take me with him when he went to sea again. I believed, that it would some time, when this sea rover will be taken by a Spanish or Portugal man‑of‑war, and that then I should be set at liberty.

But this hope of mine was soon taken away; for when he went to sea, he left me on shore to look after his little garden, and do the common domestic things about his house; and when he came home again from his cruise, he ordered me to lie in the cabin on board to look after the ship.

For two long years I had been a miserable slave of my patron, and all my thoughts were only about the escape and release. Most of time I spent on land, looking after the master’s household. I left the land only on the rare occasions, when my patron went on a fishing trip. He used constantly, once or twice a week, sometimes oftener if the weather was fair, to take the ship and go out into the road a‑fishing. I proved very dexterous in catching fish; insomuch that sometimes patron took me and young boy Xury, as they called him, to row the boat and to help him fishing.

Two or three times we went into a long voyage that we were two leagues from the shore, because farther from the coast line we could caught larger fish. We usually went for such a trip by our English ship, that pirate, our master, had taken. We never went a‑fishing without a compass and some provision. In the middle of the long‑boat, in our ship, there were a state‑room, and this cabin had been served as a buffet. In this buffet were stored baskets of sea biscuits, bread, rice and coffee. Every time there were about eight or ten bottles of the port wine and liquor as the master thought to drink. The reason of such a foresight and thrifty [59] of our master, was one incident that occurred shortly before.

It happened one time, that going a‑fish in a calm morning, a fog rose so thick that, though we were not half a league from the shore, we lost sight of it; we laboured all day, and all the next night and we knew not whither or which way; and when the morning came we found we had pulled off to sea instead of pulling in for the shore; and that we were at least two leagues from the shore. However, we got well in again, though with a great deal of labour [60] and some danger; for the wind began to blow pretty fresh in the morning; but we were all very hungry.

But our patron, warned by this disaster, resolved to take more care of himself for the future, therefore took all the measures to stock up with provisions and drinks. In this way, that minor incident gave me a good turn.

Since then, my thoughts of escape became stronger than ever before. I began to prepare to flee. [61]

One day it happened that he had appointed to go out in this boat, either for pleasure or for fish, with two or three Moors of some distinction in that place,[62] and for whom he had provided extraordinarily, and had, therefore, sent on board the boat overnight a larger store of provisions than ordinary; and had ordered me to get ready three fusees with powder and shot, which were on board his ship, for that they designed some sport of fowling as well as fishing.

This moment my former notions of deliverance darted into my thoughts, for now I found I was likely to have a little ship at my command. I prepared to furnish myself, not for fishing business, but for a voyage.

All the gunpowder and bullets were kept on pirate’s man‑of‑war,[63] by which he usually went on looting. So, the master ordered the Moor, called Ismael, who guarded the ship, to give me everything for fowling. And then I went on a little trick. I called to Moor – “Moely,” said I (everyone called Ismael Muley, or Moely), “our patron’s guns are on board of his English ship, can you not get a little more powder and shot? It may be we kill some alcamies (a fowl like our curlews [64]) for ourselves, for I know we must not presume to eat of our patron’s bread. We can divide all the prey equally!”

“Yes,” says he, “I’ll bring some;” and accordingly he brought a great leather pouch, which held a pound and a half of powder, or rather more; and another with shot, that had five or six pounds, with some bullets, and put all aboard the ship.

I conveyed also a great lump of beeswax [65] into the boat, which weighed about half a hundred‑weight, a hatchet, a saw, and a hammer, all of which were of great use to us afterwards, especially the wax, to make candles.

I got all things ready and waited the next morning on a board, washed clean, ready to sail; when my patron came on board alone, and told me his guests had put off going from some business that fell out, and ordered me, with the boy, Xury, as usual, to go out with ship and catch them some fish, for that his friends were to sup [66] at his house, and commanded that as soon as I got some fish I should bring it home to his house.

So, I went out to sea alone, out of the port to fish, on board of a ship full of supplies, furnished with everything needful, accompanied only by young Xury and Luck.

The castle, which is at the entrance of the port, knew who we were, and took no notice of us; and we were not above a mile out of the port before we set us down to fish.

After we had fished some time and caught nothing – for when I had fish on my hook I would not pull them up, I said to the Xury, “This will not do; our master will not be served; we must stand farther off.” He, thinking no harm,[67] agreed, and being in the head of the ship, set the sails.

When we were about two miles above the shore, I took the gun out of the cabin and went to Xury. When he saw the gun in my hands, a fear reflected on his face. I touched his shoulder and said to him,

“Xury, if you will be faithful to me, I’ll make you a great man; but if you will not be true to me, I must kill you.” The boy smiled in my face, the fear in his eyes immediately disappeared, and spoke so innocently that I could not distrust him, he swore to be faithful to me,[68] and go all over the world with me.

So, I enlisted the full support of Xury and became a full captain of our ship, and a master of one‑person crew. In fear, that our ex‑patron, pirate from Sallee, could sent us the chase,[69] I decided to make one trick: while our ship was in view from the coast line, I stood out directly to sea with the ship, that they might think me gone towards the Strait of Gibraltar [70] (as indeed any one must have been supposed to do).

But as soon as it grew dusk [71] in the evening, I changed my course, and sailed directly south and by east, bending my course a little towards the east, that I might keep in with the shore; and having a fresh wind, and a smooth, quiet sea, I made such sail that I believe by the next day, at three o’clock in the afternoon, when I first made the land,[72] I could not be less than one hundred and fifty miles south of Sallee.

During the next five or six days the tail‑wind continued to blow, though I would not stop, or come to an anchor and go on shore, yet such was the fright I had taken of Moors. I concluded, that if any of them were in chase of me, they would now give over, therefore I decided to sail near the coast line.

We sailed along the coast of Africa, close to the shore. Sometimes we heard lions and other wild beasts. We needed fresh water, but we were afraid to go ashore, for fear of wild beasts and savages. [73] However, one day, I came to an anchor in the mouth of a little river, I knew not what, nor where, neither what latitude, what country, what nation, or what river. The principal thing I wanted was fresh water.

We came into the small bay in the evening, resolving to swim on shore as soon as it was dark, and discover the country; but as soon as it was quite dark, we heard such dreadful noises of the barking and roaring of wild creatures, of we knew not what kinds. We decided to stay aboard till day, and in the morning to go ashore with two guns, some powder and shot. We were afraid not only about lions and other wild beasts, but moreover about men, who could be as bad to us as all wild creatures.

We dropped our little anchor, and lay still all night; I say still, for we slept none; for in two or three hours we saw vast great creatures (we knew not what to call them) of many sorts, come down to the sea‑shore and run into the water, wallowing and washing themselves for the pleasure of cooling themselves; and they made such hideous howlings and yellings,[74] that I never indeed heard the like.

But we were both more frighted when we heard one of these mighty creatures come swimming towards our boat; we could not see him, but we might hear him by his blowing to be a monstrous huge and furious beast. Xury said it was a lion, and I said it might be so. I had no sooner said so, but I saw the creature (whatever it was) within two oars ’ length,[75] which something surprised me; however, I immediately stepped to the cabin door, and taking up my gun, fired at him; upon which he immediately turned about and swam towards the shore again.

But it is impossible to describe the horrid noises, and hideous cries and howlings that were raised, as well upon the edge of the shore as higher within the country, upon the noise or report of the gun, a thing I have some reason to believe those creatures had never heard before.

However, we were obliged to go on shore somewhere or other for water, for we had not a pint left on a board; when and where to get to it was the point. Xury said, if I would let him go on shore with one of the jars, he would find if there was any water, and bring some to me. He said that I should stay aboard.

“Why should you go, Xury?” I asked. “Why should I not go, and you wait aboard?”

Xury replied in words that made me love him ever after: “If wild men come, they will eat me, and you will escape.”

“Well, Xury,” said I, “we will both go and if the wild men come, we will kill them, they shall eat neither of us.” So I gave Xury a piece of rusk bread [76] to eat, and a dram [77] out of our patron’s case of bottles which I mentioned before; and we moored our ship to the shore as we thought was proper,[78] and so waded on shore, carrying nothing but our arms and two jars for water.

I did not want to go out of sight of the boat, fearing the coming of canoes with savages down the river; but the boy seeing a low place about a mile up the country, rambled to it, and by‑and‑by I saw him come running towards me. I thought he was pursued by some savage, or frighted with some wild beast, and I ran forward towards him to help him; but when I came nearer to him I saw something hanging over his shoulders, which was a creature that he had shot, like a hare, but different in colour, and longer legs; however, we were very glad of it, and it was very good meat; but the great joy that poor Xury came with, was to tell me he had found good water and seen no wild beasts.

So we filled our jars, and feasted [79] on the hare he had killed, and prepared to go on our way, having seen no footsteps of any human creature in that part of the country.

As I had been one voyage to this coast of Africa before, I knew very well that the islands of the Canaries, and the Cape de Verde Islands also, lay not far off from the coast. But as I had no instruments to take an observation to know what latitude we were in, and not exactly knowing, or at least remembering, what latitude they were in, I knew not where to look for them, or when to stand off to sea towards them; otherwise I might now easily have found some of these islands. But my hope was, that if I stood along this coast till I came to that part where the English traded, I should find some of their vessels [80] upon their usual design of trade, that would relieve and take us in.

Once or twice in the daytime I thought I saw the Pico of Teneriffe,[81] being the high top of the Mountain Teneriffe in the Canaries, and had a great mind to venture out,[82] in hopes of reaching thither; but having tried twice, I was forced in again by contrary winds, the sea also going too high; so, I resolved to pursue my first design, and keep along the shore.

Several times I was obliged to land for fresh water. At once, we came to an anchor under a little point of land. Xury, whose eyes were more about him than it seems mine were, calls softly to me, and tells me that we had best go farther off the shore; “For,” says he, “look, yonder [83] lies a dreadful monster on the side of that hillock, fast asleep.” I looked where he pointed, and saw a dreadful monster indeed, for it was a terrible, great lion that lay on the side of the shore, under the shade of a piece of the hill that hung as it were a little over him. I took our biggest gun, which was almost musket‑bore,[84] and loaded it with a good charge of powder, and with two slugs. [85] I took the best aim I could with the first piece to have shot him in the head, but he lay so with his leg raised a little above his nose, that the slugs hit his leg about the knee and broke the bone. He started up, growling at first, but finding his leg broken, fell down again; and then got upon three legs, and gave the most hideous roar that ever I heard. I was a little surprised that I had not hit him on the head; however, I took up the second piece immediately, and though he began to move off, fired again, and shot him in the head, and had the pleasure to see him drop and make but little noise, but lie struggling for life. Then Xury took heart, and would have me let him go on shore. “Well, go,” said I: so the boy jumped into the water and taking a little gun in one hand, swam to shore with the other hand, and coming close to the creature, put the muzzle of the piece [86] to his ear, and shot him in the head again, which dispatched him quite.

This was game indeed to us, but this was no food; and I was very sorry to lose three charges of powder and shot upon a creature that was good for nothing to us. Xury and I took the skin off the lion, for I thought it might be of some value.

We sailed along the coast for ten or twelve days. I sailed near the shore because we need a lot of water to drink and also in the reason, that I hoped that we would meet a European trading ship and be saved, but we did not meet one.

When I had pursued this resolution about ten days longer, as I have said, I began to see that the land was inhabited; and in two or three places, as we sailed by, we saw people stand upon the shore to look at us; we could also perceive that their skin was black, and they were naked. Once I thought of going ashore to meet them, but Xury advised against it. I hauled in nearer the shore that I might talk to them, and I found they ran along the shore by me a good way. I observed they had no weapons in their hand, except one, who had a long slender stick,[87] which Xury said was a lance,[88] and that they could throw them a great way with good aim;[89] so I kept at a distance, but talked with them by signs as well as I could; and particularly made signs for something to eat: they beckoned [90] to me to stop my ship, and they would fetch me some meat. They brought meat and grain and left it on the beach for us. I made signs to thank them but had nothing to give them in payment.

However, we soon had the chance to do them a great service. Just as we reached our boat, a leopard came running down from the mountain towards the beach. I shot it dead. The Negroes were amazed and terrified by the sound of my gun. When they saw that the leopard was dead, they approached him. They wished to eat the flesh of this animal. I made signs to tell them that they could have him and they began cutting him up. They cut off his skin and gave it to us.

I was now furnished with roots and corn, such as it was, and water; and leaving my friendly negroes, I made forward for about eleven days more.

One day, I stepped into the cabin and sat down, Xury having the helm; when, on a sudden, the boy cried out, “Master, master, a ship with a sail!” and the foolish boy was frighted out of his wits, thinking it must needs be some of his master’s ships sent to pursue us, but I knew we were far enough out of their reach. I jumped out of the cabin, and immediately saw, not only the ship, but that it was a Portuguese ship; and, as I thought, was bound to the coast of Guinea, for negroes. But, when I observed the course she steered, I was soon convinced they were bound some other way, and did not design to come any nearer to the shore; upon which I stretched out to sea as much as I could, resolving to speak with them if possible.

With all the sail I could make, I found I should not be able to come in their way, but that they would be gone by before I could make any signal to them: but after I had crowded to the utmost, and began to despair, they, it seems, saw by the help of their glasses that it was some European ship, that was lost; so they shortened sail to let me come up. I was encouraged with this, and as I had my patron’s ancient on board, I made a waft of it to them, for a signal of distress, and fired a gun, both which they saw; for they told me they saw the smoke, though they did not hear the gun. Upon these signals they very kindly brought to, and lay by for me; and in about three hours; time I came up with them.

They asked me what I was, in Portuguese, and in Spanish, and in French, but I understood none of them; but at last a Scotch sailor, who was on board, called to me: and I answered him, and told him I was an Englishman, that I had made my escape out of slavery from the Moors, at Sallee; they then bade me come on board, and very kindly took me in, and all my goods.

It was an inexpressible joy to me, which any one will believe, that I was thus delivered, as I esteemed it, from such a miserable and almost hopeless condition as I was in; and I immediately offered all I had to the captain of the ship, as a return for my deliverance; but he generously told me he would take nothing from me, but that all I had should be delivered safe to me when I came to the Brazils. “For,” says he, “I have saved your life on no other terms than I would be glad to be saved myself: and it may, one time or other, be my lot to be taken up in the same condition. He said that my property would be returned to me when we arrived. He offered to buy my boat from me. He paid me eighty pieces of eight, this is a kind of silver coins,[91] two pieces of eight could buy a horse, so eighty pieces was a real treasure for me! He also offered me sixty pieces of eight for Xury, but I didn’t want to sell him. Xury had helped me to escape from slavery, so I didn’t want him to become a poor slave again. However, the captain offered to set Xury free in ten years, if he became a Christian. The boy said he was willing to go with captain, so I let the master have him.

We had a very good voyage to the Brazils, and I arrived in the Bay de Todos los Santos, or All Saints’ Bay, in about twenty‑two days after. And now I was once more delivered from the most miserable of all conditions of life; and what to do next with myself I was to consider.

The generous treatment [92] the captain gave me I can never enough remember: he would take nothing of me for my passage, gave me twenty ducats for the leopard’s skin, and forty for the lion’s skin, which I had in my boat, and caused everything I had in the ship to be punctually delivered to me; and what I was willing to sell he bought of me, such as the case of bottles, two of my guns, and a piece of the lump of beeswax – for I had made candles of the rest: in a word, I made about two hundred and twenty pieces of eight of all my cargo;[93] and with this stock I went on shore in the Brazils.

I had not been long here before I was recommended to the house of a good honest man like himself, who had an INGENIO, as they call it (that is, a plantation and a sugar‑house). I lived with him some time, and acquainted myself [94] by that means with the manner of planting and making of sugar; and seeing how well the planters lived, and how they got rich suddenly, I resolved, if I could get a licence to settle there,[95] I would turn planter among them: resolving in the meantime to find out some way to get my money, which I had left in London, remitted to me. To this purpose, getting a kind of letter of naturalisation,[96] I purchased as much land that was uncured as my money would reach, and formed a plan for my plantation and settlement; such as one as might be suitable to the stock which I proposed to myself to receive from England.

I had a neighbour, a Portuguese, of Lisbon, but born of English parents, whose name was Wells, and in much such circumstances [97] as I was. I call him my neighbour, because his plantation lay next to mine, and we went on very sociably together. My stock [98] was but low, as well as his; and we rather planted for food than anything else, for about two years. However, we began to increase, and our land began to come into order; so that the third year we planted some tobacco, and made each of us a large piece of ground ready for planting canes in the year to come. But we both wanted help; and now I found, more than before, I had done wrong in parting with my boy Xury.

Chapter III

Wrecked on a Desert Island

I was not happy in my new life. This was the middle state of which my father had spoken. I often said to myself, that I could have done this at home, instead of coming about five thousand miles to do it among strangers and savages. I had nobody to converse with, but now and then this neighbour; no work to be done, but by the labour of my hands; and I used to say, I lived just like a man cast away upon some desolate island,[99] that had nobody there but himself. I thought I was like a man stranded alone upon an island. Never compare your situation to a worse one! God may place you in the worse situation, so that you long for your old life! I say, God just to leave me on an island, where I really was alone! If I had been content to stay as I was, I would have been rich and happy. By living me on an island, God made me understand this.

My new friend, the captain of the Portuguese ship advised me to send for some money, that I had left in London, as you remember, for safekeeping to the widow of my deceased friend, captain of English ship. I wrote the widow a letter, asking to send me only the half of my money, about 100 pounds. My new friend advised her to send me the money in the form of English goods. When they arrived, I thought that my fortune was made. I sold the goods at a great profit [100] for about four hundred pounds. As soon as I got this money, I bought myself a Negro slave.

I went on the next year with great success in my plantation: I raised fifty great rolls of tobacco on my own ground, more than I had disposed of for necessaries among my neighbours; and these fifty rolls, being each of above a hundredweight. And now increasing in business and wealth, my head began to be full of projects and undertakings beyond my reach.

After four years, I had learnt the language and made some friends among my fellow planters. I had not only learned the language, but had contracted acquaintance [101] and friendship among my fellow‑planters, as well as among the merchants at St. Salvador, which was our port. I told them of the trade in Negro Slaves on the African coast, known as Guinea and that, in my discourses among them, I had frequently given them an account of my two voyages: the manner of trading with the negroes there, and how easy it was to purchase [102] upon the coast for trifles – such as beads,[103] toys, knives, scissors, hatchets, bits of glass, and the like – not only gold‑dust, Guinea grains, elephants’ teeth, but negroes, for the service of the Brazils, in great numbers. They listened always very attentively to my discourses on these heads, but especially to that part which related to the buying of negroes.

It happened, being in company with some merchants and planters, and talking of those things very earnestly, three of them came to me next morning, and told me they came to make a secret proposal to me; and, after enjoining me to secrecy,[104] they told me that they had a mind to fit out a ship to go to Guinea; that they had all plantations as well as I, and were straitened for nothing so much as servants; they desired to make one voyage, to bring the negroes on shore privately, and divide them among their own plantations; and, in a word, the question was whether I would go with them in the ship, to manage the trading part upon the coast of Guinea; and they offered me that I should have my equal share of the negroes, without spending any money. [105] So, I agreed to go. In short, I took all possible caution to preserve my effects and to keep up my plantation.

I went aboard the ship, sailed to Guinea, on the 1st September 1659, exactly eight years after my first voyage from Hull, when our board was shipwrecked. We sailed up the coast to Cape St Augustino, when we lost sight of land. Our ship was about one hundred and twenty tons burden,[106] carried six guns and fourteen men, besides the master, his boy, and myself. We had on board no large cargo of goods, except of such toys as were fit for our trade with the negroes.

In the course, we passed the line in about twelve days’ time, and were, by our last observation, in seven degrees twenty‑two minutes northern latitude, when a violent tornado, or hurricane,[107] took us quite out of our knowledge. It began from the south‑east, came about to the north‑west, and then settled in the north‑east; from whence it blew in such a terrible manner, that for twelve days together we could do nothing but drive, and, scudding away [108] before it, let it carry us whither, and, during these twelve days, I need not say that I expected every day to be swallowed up; nor, indeed, did any in the ship expect to save their lives.

We could understand, that this terrible storm blew us far away from the trading routes. We couldn’t observe neither latitude, nor longitude, we understand, if we came to land, we would probably be eaten by savages.

In this distress, the wind still blowing very hard, one of our men early in the morning cried out, “Land!” and we had no sooner run out of the cabin to look out, in hopes of seeing whereabouts in the world we were, we knew nothing where we were, or upon what land it was we were driven – whether an island or the main,[109] whether inhabited or not inhabited. Than the ship struck upon a sand, and in a moment her motion being so stopped, the sea broke over her in such a manner that we expected we should all have perished immediately; and we were immediately driven into our close quarters, to shelter us from the very foam and spray [110] of the sea. As the rage of the wind was still great, though rather less than at first, we could not so much as hope to have the ship hold many minutes without breaking into pieces.

We could not move the ship off the sand. We climbed into a boat and left the ship. We rowed through that wild water towards the land, knowing that we were rowing towards our greatest danger. What the shore was, whether rock or sand, whether steep or shoal,[111] we knew not. The only hope that could rationally give us the least shadow of expectation was, if we might find some bay or gulf, or the mouth of some river, where by great chance we might have run our boat in, or got under the lee of the land, and perhaps made smooth water.

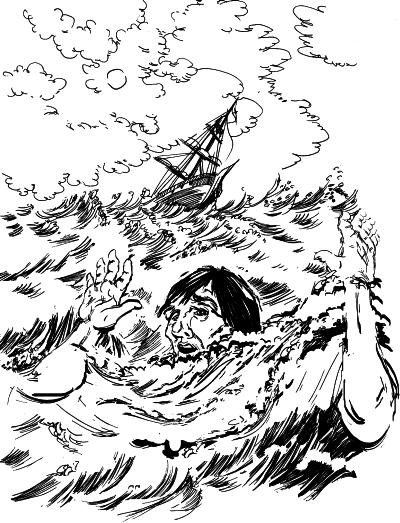

After we had rowed, or rather driven about a league and a half, a raging wave, mountain‑like, came rolling astern of us. This one separating us as well from the boat as from one another, gave us no time to say, “O God!” for we were all swallowed up in a moment.

Though I was a good swimmer, I could not get my breath in this stormy sea. The wave that came upon me again buried me at once twenty or thirty feet deep in its own body, and I could feel myself carried with a mighty force and swiftness [112] towards the shore – a very great way; but I held my breath, and assisted myself to swim still forward with all my might. I was ready to burst with holding my breath, when, as I felt myself rising up, so, to my immediate relief, I found my head and hands shoot out above the surface of the water; and though it was not two seconds of time that I could keep myself so yet it relieved me greatly, gave me breath, and new courage.

I felt the earth under my feet. I run towards the shore, but twice more the waves came over me. The last time nearly killed me. The sea threw me hard against a rock. I held on to the rock as the next wave broke over me. When the wave withdrew,[113] I ran to the beach, climbed over the rocks, and lay down on the grass.

Chapter IV

First Weeks on the Island

I was now landed and safe on shore, and began to look up and thank God that my life was saved. I believe it is impossible to express, to the life, what the transports of the soul are, when it is so saved. I can’t describe the joy of myself, who has just escaped death.

I walked about on the shore lifting up my hands, and my whole being, as I may say, wrapped up in a contemplation of my deliverance; making a thousand gestures and motions, which I cannot describe; reflecting upon all my comrades that were drowned, and that there should not be one soul saved but myself; for, as for them, I never saw them afterwards, or any sign of them, except three of their hats, one cap, and two shoes that were not fellows.

I cast my eye to the ship, when, the breach and froth of the sea being so big,[114] I could hardly see it, it lay so far of; and considered, Lord! how was it possible I could get on shore

I began to look round me, to see what kind of place I was in, and what was next to be done; and I soon found my comforts abate, and that, in a word, I had a dreadful deliverance; for I was wet, had no clothes, nor anything either to eat or drink to comfort me; neither did I see any prospect before me but that of perishing with hunger [115] or being eaten by wild beasts. Moreover, I had no gun with which to hunt for food or defend myself. In a word, I had nothing about me but a knife, a tobacco‑pipe, and a little tobacco in a box. This was all my provisions; and this threw me into such terrible agonies of mind, that for a while I ran about like a madman.

Night coming upon me, I began with a heavy heart to consider what would be if there were any wild beasts in that country, as at night they always come ashore.

I walked about a furlong from the shore, to see if I could find any fresh water to drink, which I did, to my great joy; and having drank, I put a little tobacco into my mouth to prevent hunger. I considered to get up into a thick bushy tree like a fir, but thorny, which grew near me, and where I resolved to sit all night, and consider the next day what death I should die, for as yet I saw no prospect of life.

I went to the tree, and getting up into it, tried to place myself so that if I should sleep I might not fall. I fell fast asleep, and slept as comfortably as, I believe, few could have done in my condition, and found myself more refreshed with it than, I think, I ever was on such an occasion.

When I awoke, the sun was shining. The waves had moved the ship closer to the shore during the night. I realized that if we had stayed on board that terrible day, we would all have survived the storm. This thoughts made the tears run down my face. The ship was being within about a mile from the shore where I was, and it seeming to stand upright still, I wished myself on board, that at least I might save some necessary things for my use.

When I came down from my apartment in the tree, I looked about me again, and the first thing I found was the boat, which lay, as the wind and the sea had tossed her up, upon the land, about two miles on my right hand. I walked as far as I could upon the shore till I got her. I resolved, if possible, to get to the ship by this boat.

A little after noon I found the sea very calm, so I sat into the boat, and went into the sea, in a strong wish of reaching the board of the ship.

But when I came to the ship my difficulty was to know how to get on board; for, as she lay aground, and high out of the water, there was nothing within my reach to lay hold of. I swam round her twice, and the second time I spied a small piece of rope, which I wondered I did not see at first, hung down by the fore‑chains so low, as that with great difficulty I got hold of it, and by the help of that rope I got up into the forecastle [116] of the ship.

Here I found that the ship was bulged,[117] and had a great deal of water in her hold, but that she lay so on the side of a bank of hard sand, or, rather earth, that her stern lay lifted up upon the bank, and her head low, almost to the water. By this means all her quarter was free, and all that was in that part was dry; for you may be sure my first work was to search, and to see what was spoiled [118] and what was free. And, first, I found that all the ship’s provisions were dry and untouched by the water, and being very well disposed to eat, I went to the bread room and filled my pockets with biscuit, and ate it as I went about other things, for I had no time to lose. I also found some rum in the great cabin, of which I took a large dram, and which I had, indeed, need enough of to spirit me for what was before me.

I first laid all the planks or boards upon it that I could get, and having considered well what I most wanted, I got three of the seamen’s chests, which I had broken open, and emptied, and lowered them into my boat; the first of these I filled with provisions – bread, rice, three Dutch cheeses, five pieces of dried goat’s flesh (which we lived much upon).

I found enough of clothes on board, but took no more than I wanted for present use, for I had others things which my eye was more upon – as, first, tools to work with on shore. And it was after long searching that I found out the carpenter’s chest,[119] which was, indeed, a very useful prize to me. I got it down to my boat, whole as it was, without losing time to look into it, for I knew in general what it contained.

My next care was for some ammunition and arms. There were two very good fowling‑pieces [120] in the great cabin, and two pistols. These I secured first, with some powder‑horns and a small bag of shot, and two old rusty swords. I knew there were three barrels of powder in the ship, but knew not where our gunner had stowed them; but with much search I found them, two of them dry and good, the third had taken water. Those two I got to my raft with the arms. And now I thought myself pretty well freighted, and began to think how I should get to shore with them.

I got into the boat, full over with all the goods, clothes, ammunition and arms and returned to the shore, by puddles. A short distance from where I had landed the night before, I saw a river. I landed the boat a little way up the river and got all my goods on shore.

My next work was to view the country, and seek a proper place for my habitation, and where to stow my goods to secure them from whatever might happen. Where I was, I yet knew not; whether on the continent or on an island; whether inhabited or not inhabited; whether in danger of wild beasts or not. There was a hill not above a mile from me, which rose up very steep and high, and which seemed to overtop some other hills, which lay as in a ridge from it northward. I took out one of the fowling‑pieces, and one of the pistols, and a horn of powder; and thus armed, I travelled for discovery up to the top of that hill, where, after I had with great labour and difficulty got to the top, I found that I was in an island environed every way with the sea: no land to be seen except some rocks, which lay a great way off; and two small islands, less than this, which lay about three leagues to the west.

I found also that the island I was in was barren, and, as I saw good reason to believe, uninhabited except by wild beasts, of whom, however, I saw none. Yet I saw abundance of fowls, but knew not their kinds; neither when I killed them could I tell what was fit for food, and what not. At my coming back, I shot at a great bird which I saw sitting upon a tree on the side of a great wood. I believe it was the first gun that had been fired there since the creation of the world. I had no sooner fired, than from all parts of the wood there arose an innumerable number of fowls, of many sorts, making a confused screaming and crying, and every one according to his usual note, but not one of them of any kind that I knew. As for the creature I killed, I took it to be a kind of hawk, its colour and beak resembling it, but it had no talons or claws more than common. Its flesh was carrion, and fit for nothing. Contented with this discovery, I came back to my raft, and fell to work to bring my cargo on shore, which took me up the rest of that day. What to do with myself at night I knew not, nor indeed where to rest, for I was afraid to lie down on the ground, not knowing but some wild beast might devour me, though, as I afterwards found, there was really no need for those fears.

However, as well as I could, I barricaded myself round with the chest and boards that I had brought on shore, and made a kind of hut for that night’s lodging.

Next day I began aboard the ship with the canvas. Cutting the great piece of canvas into smaller sailclothes parts, such as I could move, I got two big linen on shore, with all the ironwork I could get. I thought I had rummaged the cabin so effectually that nothing more could be found, however, one day I discovered a locker with drawers in it, in one of which I found two or three razors, and one pair of large scissors, with some ten or a dozen of good knives and forks.

During the next thirteen days I had been eleven times on board the ship. I think that if the weather had remained calm I would have brought the whole ship away piece by piece. Every day I went aboard the ship and brought a lot of good things to the shore. Finally, there was nothing more to take out of the ship. And I began to take pieces of the ship itself. I carried to the shore everything I could: such as pieces of iron, rope, nail.

I had been now thirteen days on shore, working all the day very hard. The most part of the day I spent in the sea, aboard the ship, or ashore, trying to pack all the goods and to system them. To protect all the things, especially ammunition and arms (all the powder I had) from the water, I built something like tent or hovel, with the biggest pieces of linen and some tarpaulin.

My thoughts were now wholly employed about securing myself against either savages, if any should appear, or wild beasts, if any were in the island; and I had many thoughts of the method how to do this, and what kind of dwelling to make – whether I should make me a cave in the earth, or a tent upon the earth; and, in short, I resolved upon both.

First of all I resolved to find a more healthy and more convenient spot of ground, because I soon found the place I was in was not fit for my settlement, because it was upon a low, moorish ground, near the sea, and more particularly because there was no fresh water near it.

I consulted several things in my situation, which I found would he proper for me: first, health and fresh water, I just now mentioned; secondly, shelter from the heat of the sun; thirdly, security from ravenous creatures, whether man or beast; fourthly, a view to the sea, that if God sent any ship in sight, I might not lose any advantage for my deliverance, of which I was not willing to banish all my expectation yet. In search of a place proper for this, I found a little plain on the side of a rising hill, whose front towards this little plain was steep as a house‑side, so that nothing could come down upon me from the top. On the one side of the rock there was a hollow place, worn a little way in, like the entrance or door of a cave but there was not really any cave or way into the rock at all.

First of all I built a high fence round the plain, where I was going to settle. In this half‑circle I pitched two rows of strong stakes, driving them into the ground. This cost me a great deal of time and labour, especially to cut the piles in the woods, bring them to the place, and drive them into the earth. The entrance into this place I made to be, not by a door, but by a short ladder to go over the top; which ladder, when I was in, I lifted over after me. After that I felt myself completely safe.

The next step was to built a strong tent to protect myself and all the goods from the ship. So, I made a large tent, which to preserve me from the rains that in one part of the year are very violent there, and from the scorching rays of the sun; I made double – one smaller tent within, and one larger tent above it; and covered the uppermost with a large tarpaulin, which I had saved among the sails. Into this fence or fortress, with infinite labour, I carried all my riches, all my provisions, ammunition, and stores.

And now I lay no more for a while in the bed which I had brought on shore, but in a hammock, which was indeed a very good one, and belonged to the mate of the ship. Into this tent I brought all my provisions, and everything that would spoil by the wet.

When I had done this, I began to work my way into the rock, and, in a week, I