Историки об Елизавете Петровне: Елизавета попала между двумя встречными культурными течениями, воспитывалась среди новых европейских веяний и преданий...

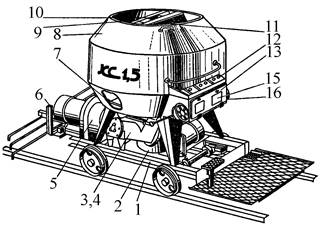

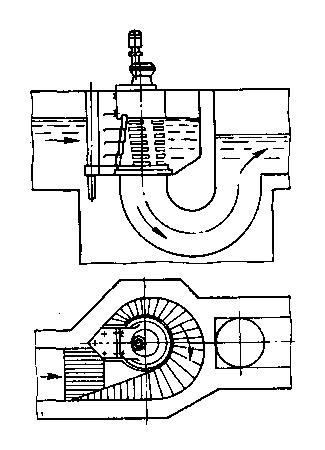

Кормораздатчик мобильный электрифицированный: схема и процесс работы устройства...

Историки об Елизавете Петровне: Елизавета попала между двумя встречными культурными течениями, воспитывалась среди новых европейских веяний и преданий...

Кормораздатчик мобильный электрифицированный: схема и процесс работы устройства...

Топ:

Методика измерений сопротивления растеканию тока анодного заземления: Анодный заземлитель (анод) – проводник, погруженный в электролитическую среду (грунт, раствор электролита) и подключенный к положительному...

Определение места расположения распределительного центра: Фирма реализует продукцию на рынках сбыта и имеет постоянных поставщиков в разных регионах. Увеличение объема продаж...

Оценка эффективности инструментов коммуникационной политики: Внешние коммуникации - обмен информацией между организацией и её внешней средой...

Интересное:

Финансовый рынок и его значение в управлении денежными потоками на современном этапе: любому предприятию для расширения производства и увеличения прибыли нужны...

Аура как энергетическое поле: многослойную ауру человека можно представить себе подобным...

Берегоукрепление оползневых склонов: На прибрежных склонах основной причиной развития оползневых процессов является подмыв водами рек естественных склонов...

Дисциплины:

|

из

5.00

|

Заказать работу |

|

|

|

|

I heard a thousand blended notes,

While in a grove I sate reclined,

In that sweet mood when pleasant thoughts

Bring sad thoughts to the mind.

To her fair works did Nature link

The human soul that through me ran;

And much it grieved my heart to think

What man has made of man.

Through primrose tufts, in that green bower,

The periwinkle trailed its wreaths;

And 'tis my faith that every flower

Enjoys the air it breathes.

The birds around me hopped and played,

Their thoughts I cannot measure: —

But the least motion which they made

It seemed a thrill of pleasure.

The budding twigs spread out their fan,

To catch the breezy air;

And I must think, do all I can,

That there was pleasure there.

If this belief from heaven be sent,

If such be Nature's holy plan,

Have I not reason to lament

What man has made of man?

СТРОКИ, НАПИСАННЫЕ РАННЕЮ ВЕСНОЙ [25]

В прозрачной роще, в день весенний

Я слушал многозвучный шум.

И радость светлых размышлений

Сменялась грустью мрачных дум.

Все, что природа сотворила,

Жило в ладу с моей душой.

Но что, — подумал я уныло, —

Что сделал человек с собой?

Средь примул, полных ликованья,

Барвинок нежный вил венок.

От своего благоуханья

Блаженствовал любой цветок.

И, наблюдая птиц круженье, —

Хоть и не мог их мыслей знать, —

Я верил: каждое движенье

Для них — восторг и благодать.

И ветки ветра дуновенье

Ловили веером своим.

Я не испытывал сомненья,

Что это было в радость им.

И коль уверенность моя —

Не наваждение пустое,

Так что, — с тоскою думал я, —

Что сделал человек с собою?

THE THORN

I

"There is a Thorn — it looks so old,

In truth, you'd find it hard to say

How it could ever have been young,

It looks so old and grey.

Not higher than a two years' child

It stands erect, this aged Thorn;

No leaves it has, no prickly points;

It is a mass of knotted joints,

A wretched thing forlorn,

It stands erect, and like a stone

With lichens is it overgrown.

II

"Like rock or stone, it is o'ergrown,

With lichens to the very top,

And hung with heavy tufts of moss,

A melancholy crop:

Up from the earth these mosses creep,

And this poor Thorn they clasp it round

|

|

So close, you'd say that they are bent

With plain and manifest intent

To drag it to the ground;

And all have joined in one endeavour

To bury this poor Thorn for ever.

III

"High on a mountain's highest ridge,

Where oft the stormy winter gale

Cuts like a scythe, while through the clouds

It sweeps from vale to vale;

Not five yards from the mountain path,

This Thorn you on your left espy;

And to the left, three yards beyond,

You see a little muddy pond

Of water-never dry

Though but of compass small, and bare

To thirsty suns and parching air.

IV

"And, close beside this aged Thorn,

There is a fresh and lovely sight,

A beauteous heap, a hill of moss,

Just half a foot in height.

All lovely colours there you see,

All colours that were ever seen;

And mossy network too is there,

As if by hand of lady fair

The work had woven been;

And cups, the darlings of the eye,

So deep is their vermilion dye.

V

"Ah me! what lovely tints are there

Of olive green and scarlet bright,

In spikes, in branches, and in stars,

Green, red, and pearly white!

This heap of earth o'ergrown with moss,

Which close beside the Thorn you see,

So fresh in all its beauteous dyes,

Is like an infant's grave in size,

As like as like can be:

But never, never any where,

An infant's grave was half so fair.

VI

"Now would you see this aged Thorn,

This pond, and beauteous hill of moss,

You must take care and choose your time

The mountain when to cross.

For oft there sits between the heap

So like an infant's grave in size,

And that same pond of which I spoke,

A Woman in a scarlet cloak,

And to herself she cries,

'Oh misery! oh misery!

Oh woe is me! oh misery!'"

VII

"At all times of the day and night

This wretched Woman thither goes;

And she is known to every star,

And every wind that blows;

And there, beside the Thorn, she sits

When the blue daylight's in the skies,

And when the whirlwind's on the hill,

Or frosty air is keen and still,

And to herself she cries,

'Oh misery! oh misery!

Oh woe is me! oh misery!'"

VIII

"Now wherefore, thus, by day and night,

In rain, in tempest, and in snow,

Thus to the dreary mountain-top

Does this poor Woman go?

And why sits she beside the Thorn

When the blue daylight's in the sky

Or when the whirlwind's on the hill,

Or frosty air is keen and still,

And wherefore does she cry? —

О wherefore? wherefore? tell me why

Does she repeat that doleful cry?"

IX

"I cannot tell; I wish I could;

For the true reason no one knows:

But would you gladly view the spot,

The spot to which she goes;

The hillock like an infant's grave,

The pond-and Thorn, so old and grey;

Pass by her door — 'tis seldom shut —

And, if you see her in her hut —

Then to the spot away!

I never heard of such as dare

Approach the spot when she is there."

X

"But wherefore to the mountain-top

Can this unhappy Woman go?

Whatever star is in the skies,

Whatever wind may blow?"

"Full twenty years are past and gone

Since she (her name is Martha Ray)

Gave with a maiden's true good-will

Her company to Stephen Hill;

And she was blithe and gay,

While friends and kindred all approved

Of him whom tenderly she loved.

|

|

XI

"And they had fixed the wedding day,

The morning that must wed them both;

But Stephen to another Maid

Had sworn another oath;

And, with this other Maid, to church

Unthinking Stephen went —

Poor Martha! on that woeful day

A pang of pitiless dismay

Into her soul was sent;

A fire was kindled in her breast,

Which might not burn itself to rest.

XII

"They say, full six months after this,

While yet the summer leaves were green,

She to the mountain-top would go,

And there was often seen.

What could she seek? — or wish to hide?

Her state to any eye was plain;

She was with child, and she was mad;

Yet often was she sober sad

From her exceeding pain.

О guilty Father-would that death

Had saved him from that breach of faith!

XIII

"Sad case for such a brain to hold

Communion with a stirring child!

Sad case, as you may think, for one

Who had a brain so wild!

Last Christmas-eve we talked of this,

And grey-haired Wilfred of the glen

Held that the unborn infant wrought

About its mother's heart, and brought

Her senses back again:

And, when at last her time drew near,

Her looks were calm, her senses clear.

XIV

"More know I not, I wish I did,

And it should all be told to you;

For what became of this poor child

No mortal ever knew;

Nay-if a child to her was born

No earthly tongue could ever tell;

And if 'twas born alive or dead,

Far less could this with proof be said;

But some remember well,

That Martha Ray about this time

Would up the mountain often climb.

XV

"And all that winter, when at night

The wind blew from the mountain-peak,

Twas worth your while, though in the dark,

The churchyard path to seek:

For many a time and oft were heard

Cries coming from the mountain head:

Some plainly living voices were;

And others, I've heard many swear,

Were voices of the dead:

I cannot think, whate'er they say,

They had to do with Martha Ray.

XVI

"But that she goes to this old Thorn,

The Thorn which I described to you,

And there sits in a scarlet cloak

I will be sworn is true.

For one day with my telescope,

To view the ocean wide and bright,

When to this country first I came,

Ere I had heard of Martha's name,

I climbed the mountain's height: —

A storm came on, and I could see

No object higher than my knee.

XVII

"'Twas mist and rain, and storm and rain:

No screen, no fence could I discover;

And then the wind! in sooth, it was

A wind full ten times over.

I looked around, I thought I saw

A jutting crag, — and off I ran,

Head-foremost, through the driving rain,

The shelter of the crag to gain;

And, as I am a man,

Instead of jutting crag, I found

A Woman seated on the ground.

XVIII

"I did not speak — I saw her face;

Her face! — it was enough for me;

I turned about and heard her cry,

'Oh misery! oh misery!'

And there she sits, until the moon

Through half the clear blue sky will go;

And, when the little breezes make

The waters of the pond to shake,

As all the country know,

She shudders, and you hear her cry,

'Oh misery! oh misery!'"

XIX

"But what's the Thorn? and what the pond?

And what the hill of moss to her?

And what the creeping breeze that comes

The little pond to stir?"

"I cannot tell; but some will say

She hanged her baby on the tree;

Some say she drowned it in the pond,

Which is a little step beyond:

But all and each agree,

The little Babe was buried there,

Beneath that hill of moss so fair.

XX

"I've heard, the moss is spotted red

With drops of that poor infant's blood;

But kill a new-born infant thus,

I do not think she could!

Some say, if to the pond you go,

And fix on it a steady view,

The shadow of a babe you trace,

A baby and a baby's face,

And that it looks at you;

Whene'er you look on it, 'tis plain

|

|

The baby looks at you again.

XXI

"And some had sworn an oath that she

Should be to public justice brought;

And for the little infant's bones

With spades they would have sought.

But instantly the hill of moss

Before their eyes began to stir!

And, for full fifty yards around,

The grass — it shook upon the ground!

Yet all do still aver

The little Babe lies buried there,

Beneath that hill of moss so fair.

XXII

"I cannot tell how this may be,

But plain it is the Thorn is bound

With heavy tufts of moss that strive

To drag it to the ground;

And this I know, full many a time,

When she was on the mountain high,

By day, and in the silent night,

When all the stars shone clear and bright,

That I have heard her cry,

'Oh misery! oh misery!

Oh woe is me! oh misery!'"

ТЕРН [26]

I

— Ты набредешь на старый Терн

И ощутишь могильный холод:

Кто, кто теперь вообразит,

Что Терн был свеж и молод!

Старик, он ростом невелик,

С двухгодовалого младенца.

Ни листьев, даже ни шипов —

Одни узлы кривых сучков

Венчают отщепенца.

И, как стоячий камень, мхом

Отживший Терн оброс кругом.

II

Обросший, словно камень, мхом

Терновый куст неузнаваем:

С ветвей свисают космы мха

Унылым урожаем,

И от корней взобрался мох

К вершине бедного растенья,

И навалился на него,

И не скрывает своего

Упорного стремленья —

Несчастный Терн к земле склонить

И в ней навек похоронить.

III

Тропою горной ты взойдешь

Туда, где буря точит кручи,

Откуда в мирный дол она

Свергается сквозь тучи.

Там от тропы шагах в пяти

Заметишь Терн седой и мрачный,

И в трех шагах за ним видна

Ложбинка, что всегда полна

Водою непрозрачной:

Ей нипочем и суховей,

И жадность солнечных лучей.

IV

Но возле дряхлого куста

Ты встретишь зрелище иное:

Покрытый мхом прелестный холм

В полфута вышиною.

Он всеми красками цветет,

Какие есть под небесами,

И мнится, что его покров

Сплетен из разноцветных мхов

Девичьими руками.

Он зеленеет, как тростник,

И пышет пламенем гвоздик.

V

О Боже, что за кружева,

Какие звезды, ветви, стрелы!

Там — изумрудный завиток,

Там — луч жемчужно-белый.

И как все блещет и живет!

Зачем же рядом Терн унылый?

Что ж, может быть, и ты найдешь,

Что этот холм чертами схож

С младенческой могилой.

Но как бы ты ни рассудил,

На свете краше нет могил.

VI

Ты рвешься к Терну, к озерку,

К холму в таинственном цветенье?

|

|

Спешить нельзя, остерегись,

Умерь на время рвенье:

Там часто Женщина сидит,

И алый плащ ее пылает;

Она сидит меж озерком

И ярким маленьким холмом

И скорбно повторяет:

"О, горе мне! О, горе мне!

О, горе, горе, горе мне!"

VII

Несчастная туда бредет

В любое время дня и ночи;

Там ветры дуют на нее

И звезд взирают очи;

Близ Терна Женщина сидит

И в час, когда лазурь блистает,

И в час, когда из льдистых стран

Над ней проносится буран, —

Сидит и причитает:

"О, горе мне! О, горе мне!

О, горе, горе, горе мне!"

VIII

— Молю, скажи, зачем она

При свете дня, в ночную пору,

Сквозь дождь и снег и ураган

Взбирается на гору?

Зачем близ Терна там сидит

И в час, когда лазурь блистает,

И в час, когда из льдистых стран

Над ней проносится буран, —

Сидит и причитает?

Молю, открой мне, чем рожден

Ее унылый долгий стон?

IX

— Не знаю; никому у нас

Загадка эта не под силу.

Ты убедишься: холм похож

На детскую могилу,

И мутен пруд, и мрачен Терн.

Но прежде на краю селенья

Взгляни в ее убогий дом,

И ежели хозяйка в нем,

Тогда лови мгновенье:

При ней никто еще не смел

Войти в печальный тот предел.

X

— Но как случилось, что она

На это место год от году

Приходит под любой звездой,

В любую непогоду?

— Лет двадцать минуло с поры,

Как другу Марта Рэй вручила

Свои мечты и всю себя,

Вручила, страстно полюбя

Лихого Стива Хилла.

Как беззаботна, весела,

Как счастлива она была!

XI

Родня благословила их

И объявила день венчанья;

Но Стив другой подруге дал

Другое обещанье;

С другой подругой под венец

Пошел, ликуя, Стив беспечный.

А Марта, — от несчастных дум

В ней скоро помрачился ум,

И вспыхнул уголь вечный,

Что тайно пепелит сердца,

Но не сжигает до конца.

XII

Так полугода не прошло,

Еще листва не пожелтела,

А Марта в горы повлеклась,

Как будто что хотела

Там отыскать — иль, может, скрыть.

Все замечали поневоле,

Что в ней дитя, а разум дик

И чуть светлеет лишь на миг

От непосильной боли.

Уж лучше б умер подлый Стив,

Ее любви не оскорбив!

XIII

О, что за грусть! Вообрази,

Как помутненный ум томится.

Когда под сердцем все сильней

Младенец шевелится!

Седой Джером под Рождество

Нас удивил таким рассказом:

Что, в матери набравшись сил,

Младенец чудо сотворил,

И к ней вернулся разум,

И очи глянули светло;

А там и время подошло.

XIV

Что было дальше — знает Бог,

А из людей никто не знает;

В селенье нашем до сих пор

Толкуют и гадают,

Что было — или быть могло:

Родился ли ребенок бедный,

И коль родился, то каким,

Лишенным жизни иль живым,

И как исчез бесследно.

Но только с тех осенних дней

Уходит в горы Марта Рэй.

XV

|

|

Еще я слышал, что зимой

При вьюге, любопытства ради,

В ночи стекались смельчаки

К кладбищенской ограде:

Туда по ветру с горных круч

Слетали горькие рыданья,

А может, это из гробов

Рвались наружу мертвецов

Невнятные стенанья.

Но вряд ли был полночный стон

К несчастной Марте обращен.

XVI

Одно известно: каждый день

Наверх бредет она упорно

И там в пылающем плаще

Тоскует возле Терна.

Когда я прибыл в этот край

И ничего не знал, то вскоре

С моей подзорною трубой

Я поспешил крутой тропой

Взглянуть с горы на море.

Но смерклось так, что я не мог

Увидеть собственных сапог.

XVII

Пополз туман, полился дождь,

Мне не было пути обратно,

Тем более что ветер вдруг

Окреп десятикратно.

Я озирался, я спешил

Найти убежище от шквала,

И, что-то смутно увидав,

Я бросился туда стремглав,

И предо мной предстала —

Нет, не расселина в скале,

Но Женщина в пустынной мгле.

XVIII

Я онемел — я прочитал

Такую боль в погасшем взоре,

Что прочь бежал, а вслед неслось:

"О, горе мне! О, горе!"

Мне объясняли, что в горах

Она сидит безгласной тенью,

Но лишь луна взойдет в зенит

И воды озерка взрябит

Ночное дуновенье,

Как раздается в вышине:

"О, горе, горе, горе мне!"

XIX

— И ты не знаешь до сих пор,

Как связаны с ее судьбою

И Терн, и холм, и мутный пруд,

И веянье ночное?

— Не знаю; люди говорят,

Что мать младенца удавила,

Повесив на кривом сучке;

И говорят, что в озерке

Под полночь утопила.

Но все сойдутся на одном:

Дитя лежит под ярким мхом.

XX

Еще я слышал, будто холм

От крови пролитой багрится —

Но так с ребенком обойтись

Навряд ли мать решится.

И будто — если постоять

Над той ложбинкою нагорной,

На дне дитя увидишь ты,

И различишь его черты,

И встретишь взгляд упорный:

Какой бы в небе ни был час,

Дитя с тебя не сводит глаз.

XXI

А кто-то гневом воспылал

И стал взывать о правосудье;

И вот с лопатами в руках

К холму явились люди.

Но тот же миг перед толпой

Цветные мхи зашевелились,

И на полета шагов вокруг

Трава затрепетала вдруг,

И люди отступились.

Но все уверены в одном:

Дитя зарыто под холмом.

XXII

Не знаю, так оно иль нет;

Но только Терн по произволу

Тяжелых мрачных гроздьев мха

Все время гнется долу;

И сам я слышал с горных круч

Несчастной Марты причитанья;

И днем, и в тишине ночной

Под ясной блещущей луной

Проносятся рыданья:

"О, горе мне! О, горе мне!

О, горе, горе, горе мне!"

THE LAST OF THE FLOCK

I

In distant countries have I been,

And yet I have not often seen

A healthy man, a man full grown,

Weep in the public roads, alone.

But such a one, on English ground,

And in the broad highway, I met;

Along the broad highway he came,

His cheeks with tears were wet:

Sturdy he seemed, though he was sad;

And in his arms a Lamb he had.

II

He saw me, and he turned aside,

As if he wished himself to hide:

And with his coat did then essay

To wipe those briny tears away.

I followed him, and said, "My friend,

What ails you? wherefore weep you so?"

— "Shame on me, Sir! this lusty Lamb,

He makes my tears to flow.

To-day I fetched him from the rock;

He is the last of all my flock.

III

"When I was young, a single man,

And after youthful follies ran,

Though little given to care and thought,

Yet, so it was, an ewe I bought;

And other sheep from her I raised,

As healthy sheep as you might see;

And then I married, and was rich

As I could wish to be;

Of sheep I numbered a full score,

And every year increased my store.

IV

"Year after year my stock it grew;

And from this one, this single ewe,

Full fifty comely sheep I raised,

As fine a flock as ever grazed!

Upon the Quantock hills they fed;

They throve, and we at home did thrive:

— This lusty Lamb of all my store

Is all that is alive;

And now I care not if we die,

And perish all of poverty.

V

"Six Children, Sir! had I to feed:

Hard labour in a time of need!

My pride was tamed, and in our grief

I of the Parish asked relief.

They said, I was a wealthy man;

My sheep upon the uplands fed,

And it was fit that thence I took

Whereof to buy us bread.

'Do this: how can we give to you,'

They cried, 'what to the poor is due?'

VI

"I sold a sheep, as they had said,

And bought my little children bread,

And they were healthy with their food

For me-it never did me good.

A woeful time it was for me,

To see the end of all my gains,

The pretty flock which I had reared

With all my care and pains,

To see it melt like snow away —

For me it was a woeful day.

VII

"Another still! and still another!

A little lamb, and then its mother!

It was a vein that never stopped —

Like blood drops from my heart they dropped.

'Till thirty were not left alive

They dwindled, dwindled, one by one

And I may say, that many a time

I wished they all were gone —

Reckless of what might come at last

Were but the bitter struggle past.

VIII

"To wicked deeds I was inclined,

And wicked fancies crossed my mind;

And every man I chanced to see,

I thought he knew some ill of me:

No peace, no comfort could I find,

No ease, within doors or without;

And, crazily and wearily

I went my work about;

And oft was moved to flee from home,

And hide my head where wild beasts roam.

IX

"Sir! 'twas a precious flock to me

As dear as my own children be;

For daily with my growing store

I loved my children more and more.

Alas! it was an evil time;

God cursed me in my sore distress;

I prayed, yet every day I thought

I loved my children less;

And every week, and every day,

My flock it seemed to melt away.

X

"They dwindled, Sir, sad sight to see!

From ten to five, from five to three,

A lamb, a wether, and a ewe; —

And then at last from three to two;

And, of my fifty, yesterday

I had but only one:

And here it lies upon my arm,

Alas! and I have none; —

To-day I fetched it from the rock;

It is the last of all my flock."

ПОСЛЕДНИЙ ИЗ СТАДА [27]

I

Прошла в скитаньях жизнь моя,

Но очень редко видел я,

Чтобы мужчина, полный сил,

Так безутешно слезы лил,

Как тот, какого повстречал

Я на кругах родной земли:

Он по дороге шел один,

И слезы горькие текли.

Он шел, не утирая слез,

И на плечах ягненка нес.

II

Своею слабостью смущен,

Стыдясь, отворотился он,

Не смея поглядеть в упор,

И рукавом глаза утер.

— Мой друг, — сказал я, — что с тобой?

О чем ты? Что тебя гнетет?

— Заставил плакать, добрый сэр,

Меня ягненок этот вот,

Последний, — с нынешнего дня

Нет больше стада у меня…

III

Я смолоду беспечен был;

Но, образумившись, купил

Овцу — не зная, есть ли прок

В таких делах, но в должный срок

Моя овца, на радость мне,

Хороших принесла ягнят;

Желания мои сбылись —

Женился я и стал богат.

Плодились овцы; что ни год

Со стадом вместе рос доход.

IV

От лета к лету время шло,

И все росло овец число,

И вот их стало пятьдесят,

Отборных маток и ягнят!

Для них был раем горный луг,

Для нас был раем наш очаг…

Один ягненок уцелел —

Его несу я на плечах,

И пусть нам сгинуть суждено

От нищеты — мне все равно.

V

Я шестерых детей кормил,

На это не хватало сил

В неурожайный, горький год —

Я попросил помочь приход.

А мне сказали: "Ты богат —

Богатство на лугу твоем,

А хочешь хлеба — обходись

Своим нетронутым добром.

Приходский хлеб — для бедноты,

Его просить не смеешь ты!"

VI

Овцу я продал, и моя

Досыта стала есть семья,

Окрепли дети — мне ж кусок

И горек был, и шел не впрок.

Настала страшная пора,

Смятение вошло в мой дом:

Овечье стадо — мой оплот,

Моим же созданный трудом, —

Как снег растаяло, и нас

Настиг беды и скорби час.

VII

Еще овца, еще одна

Покинуть пастбище должна!

И каждая из них была

Как капля крови. Кровь текла

Из ран моих — вот так пустел

Мой луг, и сколько там в живых,

Я не считал — я лишь мечтал,

Чтоб не осталось вовсе их,

Чтоб волю дать судьбе слепой,

Чтоб кончить горький этот бой!

VIII

Я замкнут стал, я стал угрюм,

Мутился ум от черных дум,

В грехах подозревал я всех

И сам способен стал на грех.

Печален дом, враждебен мир,

И навсегда ушел покой,

Устало к своему концу

Я шел, охваченный тоской;

Порой хотелось бросить дом

И жить в чащобах, со зверьем.

IX

Таких овец не видел свет,

Цены им не было и нет;

Клянусь, я поровну любил

Детей — и тех, кто их кормил, —

Моих овец… И вот, молясь,

Я думал, что, наверно, Бог

Карал за то, что больше я

Своих детей любить бы мог…

Редело стадо с каждым днем,

Овец все меньше было в нем.

X

Все горше было их считать!

Вот их пятнадцать, десять, пять,

Их три, — уж близко до конца! —

Ягненок, валух и овца…

Из стада в пятьдесят голов

Один остался, да и тот,

Оставшийся, из рук моих

В чужие руки перейдет,

Последний, — с нынешнего дня

Нет больше стада у меня…

THE MAD MOTHER

I

Her eyes are wild, her head is bare,

The sun has burnt her coal-black hair;

Her eyebrows have a rusty stain,

And she came far from over-the main.

She has a baby on her arm,

Or else she were alone:

And underneath the hay-stack warm,

And on the greenwood stone,

She talked and sung the woods among,

And it was in the English tongue.

II

"Sweet babe! they say that I am mad,

But nay, my heart is far too glad;

And I am happy when I sing

Full many a sad and doleful thing:

Then, lovely baby, do not fear!

I pray thee have no fear of me;

But safe as in a cradle, here,

My lovely baby! thou shall be:

To thee I know too much I owe;

I cannot work thee any woe.

III

"A fire was once within my brain;

And in my head a dull, dull pain;

And fiendish faces, one, two, three,

Hung at my breast, and pulled at me;

But then there came a sight of joy;

It came at once to do me good;

I waked, and saw my little boy,

My little boy of flesh and blood;

Oh joy for me that sight to see!

For he was here, and only he.

IV

"Suck, little babe, oh suck again!

It cools my blood; it cools my brain:

Thy lips I feel them, baby! they

Draw from my heart the pain away.

Oh! press me with thy little hand;

It loosens something at my chest;

About that tight and deadly band

I feel thy little fingers prest.

The breeze I see is in the tree:

It comes to cool my babe and me.

V

"Oh! love me, love me, little boy!

Thou art thy mother's only joy;

And do not dread the waves below,

When o'er the sea-rock's edge we go;

The high crag cannot work me harm,

Nor leaping torrents when they howl;

The babe I carry on my arm,

He saves for me my precious soul;

Then happy lie; for blest am I;

Without me my sweet babe would die.

VI

"Then do not fear, my boy! for thee

Bold as a lion will I be;

And I will always be thy guide,

Through hollow snows and rivers wide.

I'll build an Indian bower; I know

The leaves that make the softest bed:

And, if from me thou wilt not go,

But still be true till I am dead,

My pretty thing! then thou shall sing

As merry as the birds in spring.

VII

"Thy father cares not for my breast,

Tis thine, sweet baby, there to rest;

Tis all thine own! — and, if its hue

Be changed, that was so fair to view,

'Tis fair enough for thee, my dove!

My beauty, little child, is flown,

But thou wilt live with me in love,

And what if my poor cheek be brown?

Tis well for me, thou canst not see

How pale and wan it else would be.

VIII

"Dread not their taunts, my little Life;

I am thy father's wedded wife;

And underneath the spreading tree

We two will live in honesty.

If his sweet boy he could forsake,

With me he never would have stayed:

From him no harm my babe can take;

But he, poor man! is wretched made;

And every day we two will pray

For him that's gone and far away.

IX

"I'll teach my boy the sweetest things:

I'll teach him how the owlet sings.

My little babe! thy lips are still,

And thou hast almost sucked thy fill.

— Where art thou gone, my own dear child?

What wicked looks are those I see?

Alas! alas! that look so wild,

It never, never came from me:

If thou art mad, my pretty lad,

Then I must be for ever sad.

X

"Oh! smile on me, my little lamb!

For I thy own dear mother am:

My love for thee has well been tried:

I've sought thy father far and wide.

I know the poisons of the shade;

I know the earth-nuts fit for food:

Then, pretty dear, be not afraid:

We'll find thy father in the wood.

Now laugh and be gay, to the woods away!

And there, my babe, we'll live for aye."

БЕЗУМНАЯ МАТЬ [28]

I

По бездорожью наугад, —

Простоволоса, дикий взгляд, —

Свирепым солнцем сожжена,

В глухом краю бредет она.

И на руках ее дитя,

А рядом — ни души.

Под стогом дух переведя,

На камне средь лесной тиши

Поет она, любви полна,

И песнь английская слышна:

II

"О, мой малютка, жизнь моя!

Все говорят: безумна я.

Но мне легко, когда мою

Печаль я песней утолю.

И я молю тебя, малыш,

Не бойся, не страшись меня!

Ты словно в колыбели спишь,

И, от беды тебя храня,

Младенец мой, я помню свой

Великий долг перед тобой.

III

Мой мозг был пламенем объят,

И боль туманила мой взгляд,

И грудь жестоко той порой

Терзал зловещих духов рой.

Но, пробудясь, в себя придя,

Как счастлива я видеть вновь

И чувствовать свое дитя,

Его живую плоть и кровь!

Мной побежден кошмарный сон,

Со мной мой мальчик, только он.

IV

К моей груди, сынок, прильни

Губами нежными — они

Как бы из сердца моего

Вытягивают скорбь его.

Покойся на груди моей,

Ее ты пальчиками тронь:

Дарует облегченье ей

Твоя прохладная ладонь.

Твоя рука свежа, легка,

Как дуновенье ветерка.

V

Люби, люби меня, малыш!

Ты счастье матери даришь!

Не бойся злобных волн внизу,

Когда я на руках несу

Тебя по острым гребням скал.

Мне скалы не сулят беды,

Не страшен мне ревущий вал —

Ведь жизнь мою спасаешь ты.

Блаженна я, дитя храня:

Ему не выжить без меня.

VI

Не бойся, маленький! Поверь,

Отважная, как дикий зверь,

Твоим вожатым буду я

Через дремучие края.

Устрою там тебе жилье,

Из листьев — мягкую кровать.

И если ты, дитя мое,

До срока не покинешь мать, —

Любимый мой, в глуши лесной

Ты будешь петь, как дрозд весной.

VII

Спи на груди моей, птенец!

Ее не любит твой отец.

Она поблекла, отцвела.

Тебе ж, мой свет, она мила.

Она твоя. И не беда,

Что красота моя ушла:

Ты будешь верен мне всегда,

А в том, что стала я смугла,

Есть малый прок: ведь бледных щек

Моих не видишь ты, сынок.

VIII

Не слушай лжи, любовь моя!

С твоим отцом венчалась я.

Наполним мы в лесной тени

Невинной жизнью наши дни.

А он не станет жить со мной,

Когда тобою пренебрег.

Но ты не бойся: он не злой,

Он сам несчастен, видит Бог!

И каждым днем с тобой вдвоем

Молиться будем мы о нем.

IX

Я обучу во тьме лесов

Тебя ночному пенью сов.

Недвижны губы малыша.

Ты, верно, сыт, моя душа?

Как странно помутились вмиг

Твои небесные черты!

Мой милый мальчик, взор твой дик!

Уж не безумен ли и ты?

Ужасный знак! Коль это так —

Во мне навек печаль и мрак.

X

О, улыбнись, ягненок мой!

И мать родную успокой!

Я все сумела превозмочь:

Отца искала день и ночь,

Мне угрожали духи тьмы,

Сырой землянкой был мой дом.

Но ты не бойся, милый, мы

С тобой в лесу отца найдем.

Всю жизнь свою в лесном краю,

Сынок, мы будем как в раю".

THE IDIOT BOY

Tis eight o'clock, — a clear March night,

The moon is up, — the sky is blue,

The owlet, in the moonlight air,

Shouts from nobody knows where;

He lengthens out his lonely shout,

Halloo! halloo! a long halloo!

— Why bustle thus about your door,

What means this bustle, Betty Foy?

Why are you in this mighty fret?

And why on horseback have you set

Him whom you love, your Idiot Boy?

Scarcely a soul is out of bed;

Good Betty, put him down again;

His lips with joy they burr at you;

But, Betty! what has he to do

With stirrup, saddle, or with rein?

But Betty's bent on her intent;

For her good neighbour, Susan Gale,

Old Susan, she who dwells alone,

Is sick, and makes a piteous moan

As if her very life would fail.

There's not a house within a mile,

No hand to help them in distress;

Old Susan lies a-bed in pain,

And sorely puzzled are the twain,

For what she ails they cannot guess.

And Betty's husband's at the wood,

Where by the week he doth abide,

A woodman in the distant vale;

There's none to help poor Susan Gale;

What must be done? what will betide?

And Betty from the lane has fetched

Her Pony, that is mild and good;

Whether he be in joy or pain,

Feeding at will along the lane,

Or bringing faggots from the wood.

And he is all in travelling trim, —

And, by the moonlight, Betty Foy

Has on the well-girt saddle set

(The like was never heard of yet)

Him whom she loves, her Idiot Boy.

And he must post without delay

Across the bridge and through the dale,

And by the church, and o'er the down,

To bring a Doctor from the town,

Or she will die, old Susan Gale.

There is no need of boot or spur,

There is no need of whip or wand;

For Johnny has his holly-bough,

And with a _hurly-burly_ now

He shakes the green bough in his hand.

And Betty o'er and o'er has told

The Boy, who is her best delight,

Both what to follow, what to shun,

What do, and what to leave undone,

How turn to left, and how to right.

And Betty's most especial charge,

Was, "Johnny! Johnny! mind that you

Come home again, nor stop at all, —

Come home again, whate'er befall,

My Johnny, do, I pray you do."

To this did Johnny answer make,

Both with his head and with his hand,

And proudly shook the bridle too;

And then! his words were not a few,

Which Betty well could understand.

And now that Johnny is just going,

Though Betty's in a mighty flurry,

She gently pats the Pony's side,

On which her Idiot Boy must ride,

And seems no longer in a hurry.

But when the Pony moved his legs,

Oh! then for the poor Idiot Boy!

For joy he cannot hold the bridle,

For joy his head and heels are idle,

He's idle all for very joy.

And while the Pony moves his legs,

In Johnny's left hand you may see

The green bough motionless and dead:

The Moon that shines above his head

Is not more still and mute than he.

His heart it was so full of glee,

That till full fifty yards were gone,

He quite forgot his holly whip,

And all his skill in horsemanship:

Oh! happy, happy, happy John.

And while the Mother, at the door,

Stands fixed, her face with joy o'erflows,

Proud of herself, and proud of him,

She sees him in his travelling trim,

How quietly her Johnny goes.

The silence of her Idiot Boy,

What hopes it sends to Betty's heart!

He's at the guide-post-he turns right;

She watches till he's out of sight,

And Betty will not then depart.

Burr, burr — now Johnny's lips they burr,

As loud as any mill, or near it;

Meek as a lamb the Pony moves,

And Johnny makes the noise he loves,

And Betty listens, glad to hear it.

Away she hies to Susan Gale:

Her Messenger's in merry tune;

The owlets hoot, the owlets curr,

And Johnny's lips they burr, burr, burr,

As on he goes beneath the moon.

His steed and he right well agree;

For of this Pony there's a rumour,

That, should he lose his eyes and ears,

And should he live a thousand years,

He never will be out of humour.

But then he is a horse that thinks!

And when he thinks, his pace is slack;

Now, though he knows poor Johnny well,

Yet, for his life, he cannot tell

What he has got upon his back.

So through the moonlight lanes they go,

And far into the moonlight dale,

And by the church, and o'er the down,

To bring a Doctor from the town,

To comfort poor old Susan Gale.

And Betty, now at Susan's side,

Is in the middle of her story,

What speedy help her Boy will bring,

With many a most diverting thing,

Of Johnny's wit, and Johnny's glory.

And Betty, still at Susan's side,

By this time is not quite so flurried:

Demure with porringer and plate

She sits, as if in Susan's fate

Her life and soul were buried.

But Betty, poor good woman! she,

You plainly in her face may read it,

Could lend out of that moment's store

Five years of happiness or more

To any that might need it.

But yet I guess that now and then

With Betty all was not so well;

And to the road she turns her ears,

And thence full many a sound she hears,

Which she to Susan will not tell.

Poor Susan moans, poor Susan groans;

"As sure as there's a moon in heaven,"

Cries Betty, "he'll be back again;

They'll both be here-'tis almost ten —

Both will be here before eleven."

Poor Susan moans, poor Susan groans;

The clock gives warning for eleven;

'Tis on the stroke-"He must be near,"

Quoth Betty, "and will soon be here,

As sure as there's a moon in heaven."

The clock is on the stroke of twelve,

And Johnny is not yet in sight:

— The Moon's in heaven, as Betty sees,

But Betty is not quite at ease;

And Susan has a dreadful night.

And Betty, half an hour ago,

On Johnny vile reflections cast:

"A little idle sauntering Thing!"

With other names, an endless string;

But now that time is gone and past.

And Betty's drooping at the heart,

That happy time all past and gone,

"How can it be he is so late?

The Doctor, he has made him wait;

Susan! they'll both be here anon."

And Susan's growing worse and worse,

And Betty's in a sad _quandary_;

And then there's nobody to say

If she must go, or she must stay!

— She's in a sad _quandary_.

The clock is on the stroke of one;

But neither Doctor nor his Guide

Appears along the moonlight road;

There's neither horse nor man abroad,

And Betty's still at Susan's side.

And Susan now begins to fear

Of sad mischances not a few,

That Johnny may perhaps be drowned;

Or lost, perhaps, and never found;

Which they must both for ever rue.

She prefaced half a hint of this

With, "God forbid it should be true!"

At the first word that Susan said

Cried Betty, rising from the bed,

"Susan, I'd gladly stay with you.

"I must be gone, I must away:

Consider, Johnny's but half-wise;

Susan, we must take care of him,

If he is hurt in life or limb" —

"Oh God forbid!" poor Susan cries.

"What can I do?" says Betty, going,

"What can I do to ease your pain?

Good Susan tell me, and I'll stay;

I fear you're in a dreadful way,

But I shall soon be back again."

"Nay, Betty, go! good Betty, go!

There's nothing that can ease my pain."

Then off she hies; but with a prayer

That God poor Susan's life would spare,

Till she comes back again.

So, through the moonlight lane she goes,

And far into the moonlight dale;

And how she ran, and how she walked,

And all that to herself she talked,

Would surely be a tedious tale.

In high and low, above, below,

In great and small, in round and square,

In tree and tower was Johnny seen,

In bush and brake, in black and green;

Twas Johnny, Johnny, every where.

And while she crossed the bridge, there came

A thought with which her heart is sore —

Johnny perhaps his horse forsook,

To hunt the moon within the brook,

And never will be heard of more.

Now is she high upon the down,

Alone amid a prospect wide;

There's neither Johnny nor his Horse

Among the fern or in the gorse;

There's neither Doctor nor his Guide.

"O saints! what is become of him?

Perhaps he's climbed into an oak,

Where he will stay till he is dead;

Or, sadly he has been misled,

And joined the wandering gipsy-folk.

"Or him that wicked Pony's carried

To the dark cave, the goblin's hall;

Or in the castle he's pursuing

Among the ghosts his own undoing;

Or playing with the waterfall."

At poor old Susan then she railed,

While to the town she posts away;

"If Susan had not been so ill,

Alas! I should have had him still,

My Johnny, till my dying day."

Poor Betty, in this sad distemper,

The Doctor's self could hardly spare:

Unworthy things she talked, and wild;

Even he, of cattle the most mild,

The Pony had his share.

But now she's fairly in the town,

And to the Doctor's door she hies;

Tis silence all on every side;

The town so long, the town so wide,

Is silent as the skies.

And now she's at the Doctor's door,

She lifts the knocker, rap, rap, rap;

The Doctor at the casement shows

His glimmering eyes that peep and doze!

And one hand rubs his old night-cap.

"O Doctor! Doctor! where's my Johnny?"

"I'm here, what is't you want with me?"

"O Sir! you know I'm Betty Foy,

And I have lost my poor dear Boy,

You know him-him you often see;

"He's not so wise as some folks be:"

"The devil take his wisdom!" said

The Doctor, looking somewhat grim,

"What, Woman! should I know of him?"

And, grumbling, he went back to bed!

"O woe is me! О woe is me!

Here will I die; here will I die;

I thought to find my lost one here,

But he is neither far nor near,

Oh! what a wretched Mother I!"

She stops, she stands, she looks about;

Which way to turn she cannot tell.

Poor Betty! it would ease her pain

If she had heart to knock again;

— The clock strikes three — a dismal knell!

Then up along the town she hies,

No wonder if her senses fail;

This piteous news so much it shocked her,

She quite forgot to send the Doctor,

To comfort poor old Susan Gale.

And now she's high upon the down,

And she can see a mile of road:

"O cruel! I'm almost threescore;

Such night as this was ne'er before,

There's not a single soul abroad."

She listens, but she cannot hear

The foot of horse, the voice of man;

The streams with softest sound are flowing,

The grass you almost hear it growing,

You hear it now, if e'er you can.

The owlets through the long blue night

Are shouting to each other still:

Fond lovers! yet not quite hob nob,

They lengthen out the tremulous sob,

That echoes far from hill to hill.

Poor Betty now has lost all hope,

Her thoughts are bent on deadly sin,

A green-grown pond she just has past,

And from the brink she hurries fast,

Lest she should drown herself therein.

And now she sits her down and weeps;

Such tears she never shed before;

"Oh dear, dear Pony! my sweet joy!

Oh carry back my Idiot Boy!

And we will ne'er o'erload thee more."

A thought is come into her head:

The Pony he is mild and good,

And we have always used him well;

Perhaps he's gone along the dell,

And carried Johnny to the wood.

Then up she springs as if on.wings;

She thinks no more of deadly sin;

If Betty fifty ponds should see,

The last of all her thoughts would be

To drown herse

|

|

|

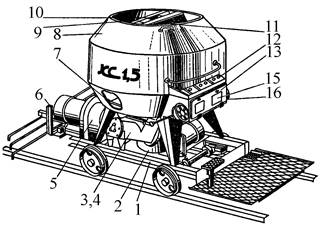

Архитектура электронного правительства: Единая архитектура – это методологический подход при создании системы управления государства, который строится...

Биохимия спиртового брожения: Основу технологии получения пива составляет спиртовое брожение, - при котором сахар превращается...

Состав сооружений: решетки и песколовки: Решетки – это первое устройство в схеме очистных сооружений. Они представляют...

Поперечные профили набережных и береговой полосы: На городских территориях берегоукрепление проектируют с учетом технических и экономических требований, но особое значение придают эстетическим...

© cyberpedia.su 2017-2024 - Не является автором материалов. Исключительное право сохранено за автором текста.

Если вы не хотите, чтобы данный материал был у нас на сайте, перейдите по ссылке: Нарушение авторских прав. Мы поможем в написании вашей работы!