Awareness of American social and economic life was characteristic of the literature of the realistic movement.

By 1870 the country had already begun to experience the abuses and dislocations that accompany a rapid change in the character of bourgeois civilization. By the end of the century the public and private morality of the country had reached its lowest point, the period being called by Mark Twain "The Gilded Age" and by others "The Tragic Era". Enlarged demand for labour had attracted immigrants in such numbers that there were nearly seven and a half million foreign born among a population of about forty million.

In the cities, crowded with newcomers, fortunes were quickly made and lost amid a general atmosphere of speculation and trickery, and the mansions of the new millionaires burgeoned in contrast with the poverty of the new slums.

The gap between the rich and the poor rapidly widened in industrial centres. The vast number of workers began to form a working class; the working conditions being still almost unregulated; reform movements and labour unrest appeared in successive waves of protest.

The second half of the XIX century and the beginning of the XX century are marked by the growth of realistic tendencies in American literature. Although the writers of this period were sternly aware of the social and economic problems, that confronted the country, their emphasis was on the character of the individuals, their hardships or moral dilemmas. But gradually the works of many American writers began to reflect the social contradictions

of capitalist society as well as to expose the tragic character of American life with its contrast of poverty and wealth.

Among the most oustanding American realists at the turn of the century who responded in their works to the existing social and economic problems were Frank Norris, Mark Twain, Theodore Dreiser, Jack London,

Frank Norris's (1870—1902) works are marked by a definite tendency towards critical realism. His novel "The Octopus" (1901) is a novel of social protest against monopoly capital and reflects the mood of the farmer masses driven to poverty by the big landowners.

In many of his works Mark Twain exposes the aggressive policy of the American Government At the same time he shows the power of gold that ruies the country, the hypocrisy and ignorance of the ruling classes and exposes the social injustice of American "democracy".

Jack London when at the height of his creative activity, produced works reflecting social contradictions of capitalist society, described the misery of the poor, the revolutionary struggle of the working class, foretold the inevitable downfall of capitalism and the final victory of socialism.

From the very beginning of his literary work Theodore Dreiser opposed the bourgeois writers who idealised capitalist America, revealing in his works the truth of American life. All his novels are a masterly description of the gross injustice of American capitalism.

Thus the emerging modern American literature which began with the optimistic voice of Walt Whitman (1819—1892) closed the first half of the XX century with a social and economic protest.

MARK TWAIN

(1835—1910)

Mark Twain [tweinj is the pen-name of Samuel Langhorne Clemens, one of the greatest figures in American literature. He is known as a humorist and satirist of remarkable force. Mark Twain believed that nothing can stand against, the assault of laughter. And we hear his laughter, now playful and boisterous, now bitter and sneering almost in all his writings.

Samuel Langhorne Clemens was born in a lawyer's family in a very small town called Florida in Missouri. Samuel Clemens spent his boyhood in Hannibal, on the Mississippi River. He saw the Negroes chained like animals for transportation to richer slave markets to the South. Sam's father owned and hired slaves. Remembering those days the writer says, "AH the Negroes were friends of ours and with those of our age we were in effect com-

rades. I say in effect, using the phrase as a modification. We were comrades yet not comrades; colour and condition interposed a subtle line which both parties were conscious of and which rendered complete fusion impossible."

In 1839 the family moved to Hannibal — immortalized as St. Petersburg in "Tom Sawyer",

When Samuel was twelve, his father died and the boy had to earn his own living. For about ten years he worked as printer and journalist in the office of the Hannibal Journal. His schooling was brief and at the age of 18 he went to Philadelphia, New York and Washington doing newspaper work and sending his first travel letters to his brother who published them in the Journal.

In April 1857, while on the way from Cincinnati to New Orleans, Clemens apprenticed himself as a river pilot; he was licensed two years later and continued in that profession until the Civil War closed the river (1861). "Piloting on the Mississippi was not work time," he recorded, "it was play — delightful play — adventurous play — and I loved it I got personally and familiarly acquainted with about all the different types of human nature... When I find a well-drawn character in fiction or biography I generally take a warm personal interest in him, for the reason that I have known him before — met him on the river."

His nostalgic love for the river life was forever fixed in his pseudonym "Mark Twain"1, the leadsman's cry.

He spent six years in Nevada, digging gold. On rainy days when the mines stopped working he wrote sketches which were published in the Territorial Enterprise, a daily paper of Virginia City.

In 1864 he made the acquaintance of Bret Harte, a well-known American writer, who influenced him greatly. A year later (1865) he won national fame with "The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County".

In 1866 Mark Twain ended his literary apprenticeship and began a brilliant platform career with a lecture on the Hawaii. The popularity of the travel letters in the Sacramento Union brought him a commission from the Alta California of San Francisco to do a similar series about a trip to New York via Nicaragua — a commission later extended to include a Mediterranean tour. Thus a series of letters was written as Mark Twain's first important book "The Innocents Abroad" (1869) — a tale of a tour in Europe and the East made by a group of Americans on board a steamer.

The fun consists of seeing Europe, its scenes and customs viewed through the eyes of an "innocent" American. The work was a great success on both sides of the Atlantic and won Twain the reputation of the most celebrated American humorist.

1 twain — 2; here: two fathoms deep; a fathom— a measure of depth (= six feet)

1 twain — 2; here: two fathoms deep; a fathom— a measure of depth (= six feet)

Before the book appeared its author had met Olivia Langdon, whom he married in 1870.

From August 1869 to April 1871 Mark Twain was an editor of the Buffalo Express. The venture was unhappy emotionally and financially. In October 1871 Mark Twain moved to Hartford which remained his home for the best and happiest years of his life.

In his first novel "The Gilded Age" (1873) written in collaboration with Charles Duddley Warner, he ridiculed the corruption, the social ignorance and stupidity of contemporary bourgeois society. The victory of the North in its struggle against the slave-owning South gave an impetus to the further development of capitalism in America. The reactionary bourgeois writers of the time described the post Civil War period as the "Golden Age'*, but Mark Twain was of a different opinion. He clearly saw the unscrupulous-ness of the American businessmen, the fantastic speculations and the corruption of the state apparatus of the USA. However, he still had some illusion concerning American bourgeois democracy which he discarded only later.

"The Adventures of Tom Sawyer" (1876). Mark Twain wrote about his book as follows: "Most of the adventures in this book are real, One or two were my own experiences, the rest of" boys' who were my school friends. Becky Thatcher is Laura Hawkins, Tom Sawyer is largely a self-portrait but Tom Blankenship, who lived just over the back fence, is the immortal Huckleberry Finn who slept on doorsteps in fine weather and in empty hogsheads in wet. John Biggs was the real, flesh-and-blood version of Joe Harper, The Terror of the Seas. My book is mainly for boys and girls to enjoy, but I hope, men and women will also be glad to read it to see what they once were like."

In "Tom Sawyer" Mark Twain lets us feel that there is a great difference between the world as it appears to a light-hearted boy and what it really is. With Tom's adventures we get to know the life on the Mississippi and that of the provincial towns of the USA in the XIX century.

Describing different comical situations Mark Twain laughs at the philistine life of St. Petersburg ridicules the bigotry and stupidity of its inhabitants.

Tom is tired of aunt Polly's morals who wants to make a decent boy out of him. He does not like school because of cramming and the teachers who beat the pupils. Tom envies Huck who can do whatever he pleases and is not looked after. Tom's protest against such life finds expression in different pranks. He misses lessons, fights his brother Sid and plays tricks on his teachers.

From books about Robin Hood, robbers and hidden treasure Tom Sawyer has created an imaginary world which differs from the one he lives in.

The book combines the elements of realism and romanticism. The realistic picture of the small town with its stagnant life is

,256

contrasted to the romantic world of Tom and his friends. It praises humanism, friendship, courage and condemns injustice, narrow-mindedness and moneyworship.

"The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn" (1884) may be considered a sequel to "Tom Sawyer". The latter two are the most favourite books of children all over the world.

"The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn", the story of a little tramp, is perhaps Twain's best work. Huck Finn recounts his adventures after being taken away from the widow Douglas by his drunken and roguish father. He escapes from his father and joins up with a runaway slave Jim.

Huck's life is different from that of Tom's and his attitude to it is more serious. Tom Sawyer remains boy who does not know any difficulties in.life while Huck acquires experience, sees and suffers much. His character is close to the author who values Huck's humanism above all. This is best revealed in Huck's attitude towards Negro Jim. Huck does not at once come to the conclusion to free Jim. Being brought up in the country where slavery is quite natural, Huck has to battle with his conscience for according to the morals of society and church he should report Jim as a runaway slave. However, the feelings of humanism get the better of the deeprooted prejudices and his final decision is in Jim's favour.

In "Huck Finn" Mark Twain presents a broad panorama of American life. Huck and Jim sail down the Mississippi, the busiest American waterway, passing big and small towns, numerous villages and lonely farms owned by free farmers whose life is full of everyday worries and hard toil. The author and his heroes critically view everything they see.

Thus the Grangerfords seem to be an ideal aristocratic family. All its members look polite, well-bred and decent people. Yet the cruel blood-feud between the Grangerford and Shepherdson families makes them kill each other.

While travelling, they happen to visit a small town in the state Arkansas where they witness a series of events. The people live in tumble-down houses, the streets are muddy. The inhabitants are lazy, rude and cruel; they delight in torturing dogs and catching runaway Negroes.

Huck and Jim seldom meet honest and good people. The majority of the people they come across are murderers, robbers, rogues. The "king" and the "duke" {two villainous tramps) lack any human qualities. They are not used to earn their living honestly. To get money, they are ready to commit any mean action, as in the case with the late Wilks' inheritance when they claim to be his brothers, or when they sell Jim into captivity.

It is to Twain's credit that he has portrayed Jim as an honest, sincere and selfless man at the time when the Negroes were considered inferior to the white people.

17 98S 257

The novel abounds in comic situations and funny incidents, however, the dominant tone of the novel is serious.

On the one hand the book is a nostalgic account of childhood, on the other — a social and moral record, a judgement of a certain epoch in America.

As his narrator Twain chose Huck who "had known and suffered all" that was on the river. Mark Twain surveys the American scene through the eyes of a teenager. He is of the opinion that children are more sensitive to contrasts — good and evil and the corruption of the world, that their insight is much keener.

The tradition to present life as seen by children, opened with Mark Twain's famous novels, continues in, modern American literature.

"The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn" marked the-growth of Mark Twain's realism. Beginning with this novel, the elements of social criticism steadily increased in the writer's works reaching their height in the satires written in the last years of his life.

Mark Twain began writing purely as a humorist, but later became a bitter satirist. Towards the end of his life he grew more and more disillusioned and dissatisfied with the American mode of life. In his later works his satire becomes sharp.

In "A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court" (1884) Mark Twain proves that there is as little or even less freedom and respect for the rights of man in his own days than there was in the times of feudal despotism.

In "The Man that Corrupted Hadleyburg" (1899) he attacks bourgeois hypocrisy and the corruption of contemporary bourgeois society. The citizens of Hadleyburg are proud of their town as "the most honest and upright town in the region all about"; it is sufficient to'tempt those virtuous people with a bag of money to reveal their egoistic and greedy nature.

Mark Twain's short story "Running for Governor" is a sharp attack on the American election system. It shows the mean and brutal methods employed by bourgeois parties in order to get their candidates elected.

They use every means in their power from shameless slander to open violence. At the same time the story exposes the corruption of the American press.

Mark Twain was a very good narrator and he wrote as he talked, for the ear more than for the eye.

The characteristic feature of his works is exaggeration and mockery at the funniest moments. His mastery of colloquial style in which he was unique among his contemporaries, has influenced later writers, among them Ernest Hemingway.

The American critics try to represent Mark Twain merely as a humorist and no more. It is a useless attempt. Nothing will ever make the world blind to what Mark Twain really was. — He was not only a fine humorist, but also a realist and the author of biting

satires and many bitterly critical pages reveal a good deal of truth about America.

His other popular works are: "Life on the Mississippi" (1883), "An Encounter with an Interviewer" (1875), "In Following the Equator" (1897), "A Tramp Abroad" (a novel, 1880), "The Prince and the Pauper" (a novel, 1881), "Tom Sawyer Abroad" (a novel, 1894), "What is Man" (an essay, 1900).

An Extract from "Running for Governor"

A few months ago I was nominated for Governor of the great State of New York, to run against Mr. Stewart L. Woodford and Mr. John T. Hoffman on an independent ticket1. I somehow felt that I had one prominent advantage over these' gentlemen, and.that Was — good character. It was easy to see by the newspapers that, if ever they had known what it was to bear a good name, that time had gone by. It was plain that in these latter years they had become familiar with all manner of shameful crimes. But at the very moment that I was exalting my advantage and joying in it in secret,, there was a muddy undercurrent of discomfort "riling" the deeps of my happiness, and that was — the having to hear my name bandied about in familiar connection with those of such people. I grew more and more disturbed. Finally I wrote my grandmother about it. Her answer came quick and sharp. She said —

"You have never done one single thing in all your life to be ashamed of — not one. Look at the newspapers — look at them and comprehend what sort of characters Messrs. Woodford and Hoffman are, and then see if you are willing to lower yourself to their level and enter a public canvass with them."

It was my very thought! I did not sleep a single moment that night. But after all I could not recede. I was fully committed, and must go on with the fight.

As I was looking listlessly over the papers at breakfast I came across the paragraph, and I may truly say I never was so confounded before: —

"Perjury. — Perhaps, now that Mr. Mark Twain is before the people as a candidate for Governor, he will condescend to ex-plain how he came to be convicted of perjury by thirty-four witnesses in Wakawak Cochin China, in 1863, the intent of which perjury being to rob a poor native widow and her helpless family of a meagre plantain-patch, their only stay and support in their bereavement and desolation. Mr. Twain owes it to himself, as well

' a list of candidates put forward by the independents, i. e., by those who do not belong to any party

' a list of candidates put forward by the independents, i. e., by those who do not belong to any party

u* 259

as to the great people whose suffrages he asks, to clear this matter up. Will he do it?"

I thought I should burst with amazement! Such a cruel, heartless charge. I never had seen Cochin China! I never had heard of Wakawak! I didn't know a plantain-patch from a kangaroo! 1 did not know what to do. I was crazed and helpless. I let the day slip away without doing anything at all. The next morning the same paper had this — nothing more.

"Significant. — Mr. Twain, it will be observed, is suggestively silent about the Cochin China perjury."

[Mem. — During the rest of the campaign this paper never referred to me in any other way than as "the infamous perjurer Twain".]

I got to picking up papers apprehensively — much as one would lift a desired blanket which he had some idea might have a rattlesnake under it. One day this met my eye: —

I got to picking up papers apprehensively — much as one would lift a desired blanket which he had some idea might have a rattlesnake under it. One day this met my eye: —

"A sweet candidate, — Mr. Mark Twain, who was to make such a blighting speech at a mass meeting of the Independents last night, didn't come to time! A telegram from his physician stated that he had been knocked down by a runaway team, and his leg broken in two places — sufferer lying in great agony, and so forth, and so forth, and a lot more bosh of the same sort. And the Independents tried hard to swallow the wretched subterfuge, and pretend that they did not know what was the real reason of the absence of the abandoned creature whom they denominate their standard-bearer.

It was incredible, absolutely incredible, for a moment that it was really my name that was coupled with this disgraceful suspicion. Three long years had passed over my head since I had tasted ale, beer, wine or liquor of any kind.

This drove me to the verge of distraction. On top of this I was accused of employing toothless and incompetent old relatives to' prepare the food for the foundling hospital when I was warden. I was wavering — wavering. Andatlast, as a due and fitting climax. to the shameless persecution that party rancour had inflicted upon rrie, nine little toddling children, of all shades of colour and degrees

of raggedness, were taught to rush on to the platform at a public meeting, and clasp me around the legs and call me PA!

Г gave up. I hauled down my colours and surrendered. I was not equal to the requirements of a Gubernatorial campaign in the State of New York, and so I sent in my withdrawal from the candidacy, and in bitterness of spirit signed it.

Truly yours, once a decent man, but now Mark Twain I. P., M.T..B. S,D.T.,F. C, andL. E.1

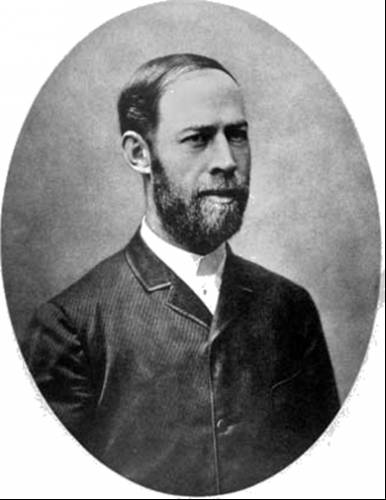

HENRY JAMES

(1843—1916)

Henry James ['henri 'd3eimz], one of the initiators of the modern psychological novel, exerted a considerable influence upon American and English readers.

He was born in New York in a cultured intellectual family which had means enough to educate their children by private tutors and send them to Europe for educational purposes. The boy attended high school in Switzerland. In 1862 James entered the Harvard Law School. After the graduation from it he began writing critical essays and articles. He visited Europe frequently and had a deep admiration for the genteel European manners and European civilization. In 1875 he finally left his native America. He felt that American culture was shallow and that American life was based upon false values of materialism and hyprocritic sham. He lived in London, Paris, Venice, Rome and Florence, associating with such famous writers as Flaubert ['flou'bea], Zola ['zoula], Turgenev and Maupassant [.moupa/sarj] who had a great influence upon his work.

His first important work of fiction was "A Passionate Pilgrim" (1871), in which he took up for the first time the theme of the American in Europe. It was followed by "The American" (1877), "The Europeans" (1878) and "Daisy Miller". His masterpiece "The Portrait of a Lady" was written in 1881. His other mature novels are "Washington Square" (1881), "The Bostonians" (1886), "The Princess Casamass-ima" [.kasa'masima] (1886) and "The Tragic Muse" (1890).

During the eighteen-nineties he turned to drama, but his plays had little success. He began writing novels again. The most important novels of his later period include "The Spoils2 of Poynton"

1 I. P. — the Infamous Perjurer, M. T. *— the Montana Thief, B. S. — the

1 I. P. — the Infamous Perjurer, M. T. *— the Montana Thief, B. S. — the

Body Snatcher, D. I. — Delirium Tremens, F. С — the Filthy Corruptiomst,

L. E. — the Loathsome Embracer.

2 booty

(1897), "The Awkward Age" (1899), "The Ambassadors" (1903) and "The Golden Bowl" (1904).'At the end of his life he wrote chiefly stories and essays on the craft of fiction. He died in London at the age of 73.

(1897), "The Awkward Age" (1899), "The Ambassadors" (1903) and "The Golden Bowl" (1904).'At the end of his life he wrote chiefly stories and essays on the craft of fiction. He died in London at the age of 73.

James has written about 40 novels. His work falls clearly into three periods:

1) his early realistic stage, including' the novels of the

seventies;

2) his mature period of psychological realism;

3) his final experimental period in which he became preoccupied

with intricate syntactical experiments and with subtleties of diction

and dialogue.

H. James' world of fiction is I rather narrow. His main heroes are usually American expatriates in Europe or English aristocracy. He does not pay any attention to the sweep of social movement in America or England. He is not particularly interested in the economic side of life. He is predominantly a historian of morals and manners, chiefly concerned with psychological subtleties. His constant themes are Jove, jealousy, loyalty and disloyalty, misunderstandings of a complicated and subtle nature, feelings of inferiority and superiority and contrasts of national character.

James is concerned with the problem of freedom. He is for the rights of the individual against all sorts of bondage. Yet it is not social bondage that he is interested in but the intangible bondage of family influences. However, James portrays not abstract "human truths", but psychologies bound to a specific social milieu' ['mi.ija;]. Long before it became the common property of other novelists and psycho-analysts he found out that something was wrong with the "well-to-do". James consistently shows the members of the upper classes as unhappy and even tragic, restless and oppressed men frustrated by their own emptiness and blindness or as the victims of cruel and evil machinations of others in the same social set.

James usually opposes the shabby codes of society to art, which alone, to his mind, embodies intrinsic human values. Despite his admiration for aristocratic English society, its good manners and seeming nobility, he portrays it as hostile to art as the vulgar business classes of America. He does not believe in the creative forces of the common people either, considering them dumb brutes doomed to animal in sensitivity. To him the artist is forever lonely in the crowd of ignorant masses. He considers that. the main source of human pleasure in art is the perfection of form. He is the conscious artist, always looking for the most effective angle or point of view from which to present'his story. ■ In his late period he experimented with modes of expression to ■arrest the fleeting moments of life as they.appeared to the indi-

1 environment 262

1 environment 262

vidual. He was interested not so much in characters or actions, but in the very flow of man's consciousness. James' later manner oi writing had a great influence upon the development of the stream-of-consciousness method in XX century literature.

"The Portrait of a Lady". This novel is the best of James' mature works. The plot concerns the development of the character of Isabel Archer ['izabel 'a'.tjVJ, a young American girl who has been left penniless by the death of her father. Taken to Europe by her aunt Mrs. Touchett ['Utjat], she attracts the attention of her invalid cousin Ralph Touchett and is courted by Lord Warburton ['woibartan], a wealthy English nobleman, and followed by her American suitor Caspar Goodwood ['keespa 'gudwud] who wants to persuade her to marry him. Her sense of freedom threatened by the aggressive masculinity of Goodwood and the conventional way of life offered to her by Lord Warburton, Isabel decides to remain unmarried, in order to develop her personality.

Ralph Touchett, who is in love with Isabel, persuades his dying father to leave her half of his fortune in order to make her independent and free of financial pressures. Isabel is a fine, free nature, intelligent and generous, "always planning out her development, desiring perfection, observing her progress". She has an immense curiosity about life. The study of her fellow creatures is her constant passion. Unluckily her thoughts of the future are a tangle of vague outlines and the uneasy question "What is she going to do with herself" troubles her mind. She devots herself to the studies of art, reading and travelling, but soon feels tired of her freedom and her vacant and barren life.

Having immnese intellectual eagerness and vague ambitions in addition to her meagre' knowledge of life, she marries Gilbert Osmond ['gilbat 'ozmgnd] who in her opinion "knows everything, understands everything", has the best taste in the world, a cultivated mind and "the kindest, gentlest, highest spirit". She hopes that their union will open new prospects to her and teach her to live the full life. She is convinced that two intelligent people caring for truth, knowledge, beauty and harmony ought to look for them together. Isabel admires Osmond's ability to bear his poverty with dignity and indifference, his secluded life devoted to thinking about art, beauty, history, his general attitude to life averse2 of the baseness and shabbiness of the surrounding world, the stupidity and ignorance of mankind.

But soon after her marriage Isabel finds out that Osmond is a fortune-hunter and a snob whose intellectual and cultural refinement hides a complete emptiness of spirit, whose "egotism lies hidden like a serpent in a bank of flowers". Their rift is widened

1 poor

1 poor

2 opposed to

2G3

. by a quarrel over Osmond's daughter Pansy ['pasnzi]. Osmond and Madame Merle {/mail], through whose efforts Isabel got acquainted with her husband, plot to marry the girl to Lord Warburton, Isabel's former suitor. Isabel is aware that Warburton still loves her and that Pansy is in love with a young man named Ned Rosier ['ned 'rouzjs], and she refuses to exert any influence on Warburton.

Soon afterwards she learns that Pansy is the illegitimate child of Osmond and Madame Merle. Disturbed by the discovery, she returns to England where Ralph is dying. There she again meets Goodwood who tries to persuade her to save what she can of her life and divorce Osmond. However, recognizing that freedom of choice entails responsibility, she rejects this last chance for happiness and returns to her husband and step-daughter, who has only her to look to for protection.

The main centre of interest in the novel is Isabel's inner growth and her search for the meaning of life. James renders with a precision and subtlety the mental processes of his heroine, her meditations on life and the people she meets with. To clarify the meaning of the fatal step Isabel takes out of her ignorance, James makes the reader see Isabel alternately through Ralph Touchett's and Lord Warburton's eyes. Her awareness of the failure of her marriage is not introduced gradually but through the objective details observed by Lord Warburton after the period of several years. And only after this we are taken into Isabel's thought stream as she bitterly ponders on her disillusionment. AH the minor characters are introduced to the reader through Isabel's eyes.

James has enriched American critical realism with his psychological novel. He is a realist of the spirit.

An Extract from "The Portrait of a Lady"

She could live it over again, the. incredulous terror with which she had taken the measure of her dwelling. Between those four wails she had lived ever since; they were to surround her for the rest of her life. It was the house of darkness, the house of dumbness, the house of suffocation. Osmond's beautiful mind gave it neither light nor air; Osmond's beautiful mind indeed seemed to peep down from a small high window and mock at her. Of course it had not been physical suffering; for physical suffering there might have been a remedy. She could come and go, she had her liberty; her husband was perfectly polite. He took himself so seriously, it was something appalling. Under all his culture, his cleverness, his amenity, under his good-nature, his facility, his knowledge of life, his egotism lay hidden like a serpent in a bank of flowers. She had taken him seriously, but she had not taken him so seriously as that. How could she — especially when she had known him better?

She was to think of him as he thought of himself -i- as the first gentleman in Europe. So it was that she had thought of him at first, and that indeed was the reason she had married him. But when she began to see. what it implied she drew back; there was more in the bond than she had meant to put her name to. It implied a sovereign contempt for every one but some three or four very exalted1 people whom he envied, and for everything in the world but half a dozen ideas of his own. That was very well, she would have gone with him even there a long distance, for he pointed out to her so much of the baseness and shabbiness of life, opened her eyes so wide to the stupidity, the depravity2, the ignorance of mankind, that she had been properly impressed with the infinite vulgarity of things and of the virtue of keeping one's self unspotted by it. But this base, ignoble3 world, it appeared, was after all what one was to live for; one was to keep it for ever in one's eye, in order not to enlighten or convert or redem4 it, but to extract from it some recognition of one's own superiority. On the one hand it was despicable, but on the other it afforded a standard. Osmond had talked to Isabel about his renunciation, his indifference, the ease with which he dispensed with the usual aids to success; and all this had seemed to her admirable. She had thought it a grand indifference, an exquisite5 independence. But indifference was really the last of his qualities; she had never seen any one who thought so much of others. For herself, avowedly6, the world had always interested her and the study of her fellow creatures been her constant passion. She would have been willing, however, to renounce all her curiosities and sympathies for the sake of a personal life, if the person concerned had only been able to make her believe it was a gain! This at least was her present conviction, and the thing certainly would have been easier than to care for society as Osmond cared for it.

He was unable to live without it, and she saw that he had never really done so; he had looked at it out of his window even when he appeared to be most detached from it. He had his ideal, just she had tried to have hers; only it was strange that people should seek for justice in such different quarters. His ideal was a conception of high prosperity, of the aristocratic life, which she now saw that he deemed himself always, in essence at least, to have led. He had never lapsed from it for an hour; he would never have recovered from the shame of doing so. That again was very well, here

1 elevated, refined; here — of high rank

1 elevated, refined; here — of high rank

2 corruption

3 base, mean

,4 to atone for

5 refined

6 openly acknowledged, admitted

too she would have agreed; but they attached such different ideas, such different associations and desires, to the same formulas. Her notion of the aristocratic life was simply the union of great knowledge with great liberty; the knowledge would give one a sense of duty and the liberty a sense of enjoyment. But for Osmond it was altogether a thing of form, a conscious, calculated attitude.

O. HENRY

(1862—1910)

O. Henry [ou'henri] (William Sidney Porter ['wiljam 'sidni 'рэ:гэ]), one of the most popular short story writers, was born in Greensboro, North Carolina. Though he read widely, his schooling was very sketchy. In 1882 he went to Texas to cure his weak lungs. He exchanged a variety of odd jobs, working as a cowboy, drugstore attendant, miner, clerk and teller1 in a bank. Finally he worked for a Houston newspaper and founded a humorous weekly, which he called The Rolling Stone.

In 1896 he was charged with embezzlement at his former job at the bank. He was not guilty. However, the case was so confused that he considered it better to flee to South America. In 1897 he returned to his dying wife to the USA and was arrested on the old charge, tried and convicted to serve five years in the penitentiary in the Ohio State prison. He started writing stones and left the prison as a mature author.

In 1902 he went to New York where he continued writing stories. Success came with "Cabbages and Kings", published in 1904. It was followed by "The Four Million" (1906), "The Trimmed Lamp1' (1907), "Heart of the West" (1907), "The Voice of the City" (1908), "The Gentle Grafter" (1908), "Roads of Destiny" (1909), "Options"' (1909) and "Strictly Business" (1910). The long years of privation and hard work had undermined the writer's health and he died at the height of his creative abilities.

O. Henry's stories depict the lives of people belonging to different layers of society ranging from unscrupulous businessmen to poor beggars. Yet, he writes most warmly of the humble classes who have proved utter failures in life. Most of his stories are romantic portrayals of pathos and sentiment surrounding the lives of shop girls, poor artists, unhappy lovers, vagabonds and burglars. However, social criticism inherent in O. Henry's stories, is very mild. As he was writing for popular magazines he often

1 a bank officer who receives and counts money paid in; and pays money out on checks

1 a bank officer who receives and counts money paid in; and pays money out on checks

had to soften the critical note of his stories by the expected traditional "happy end". Thus, in "The Third Ingredient" a poor unemployed girl is saved from suicide by a rich and noble gentleman. The story ends with wedding bells.

The writer's main interest is not in the social scene but in some unusual and paradoxical incident in the lives of his heroes. However, the paradoxes of O. Henry's stories reflect the paradoxes of American life. Thus, O. Henry often portrays the respectable businessmen as unprincipled and dishonest ("The Roads We Take"), whereas his poor people and desperados are capable of self-sacrifice ("The Purple Dress"). Even O. Henry's gentle grafters, who resort to all kinds of machinations in order to get rich are not as villainous as the bosses of industry. More often than not they fall victims to their own scheming. Thus, in "The Ransom of Red Chief" the two crooks who kidnap a boy for ransom cannot stand his antics and pranks and are forced to pay his father two hundred and fifty dollais to get rid of him. O. Henry does not look for the causes of the misery and poverty of his heroes but his humour is often tinged with sadness and bitterness, as in "The Gift of Magi", the story of Jim and Delia, a young couple, whose only treasures are Delia's beautiful long hair and Jim's gold watch. Jim sells his watch to buy Delia a comb for her hair, and she sells her hair to buy a chain for his watch.

O. Henry was a great master of the short story. He discovered practically every formula which can be used to make a trick story. One of the main secrets of the typical trick story consists in withholding an important piece of information from the reader as long as possible so that only when he finishes the story, does he fully apprehend the significance of the previous action, as in "The Gift of the Magi".

Another trick is a reversal in which a character does something for one reason but succeeds only in producing the opposite effect as in "The Cop and the Anthem", in which a tramp does everything possible to be arrested and put to prison because winter is approaching and he is homeless. His petty thievery is disregarded. Ironically, when he decides to reform, touched by an anthem, he is arrested for no reason at all.

О. Henry's stories are based almost entirely on plot. Mood and character are of less importance, though by vernacular1 intonations 0. Henry is able to bring a character swiftly to life. The soul of his art is unexpectedness. His climaxes are dramatic and his closing effect is always impressively theatric. His stories are highly condensed, being often extended anecdotes related with skill, humour and sentiment. His weakness lies in the very nature of his art.

the common mode of expression in a locality or in a profession

the common mode of expression in a locality or in a profession

Unlike M. Twain, he was an entertainer bent mainly on amusing and surprising his readers rather than analysing a human situation. Nevertheless, his racy and rapid moving prose won him millions of readers in his lifetime and after.

An Extract from "The Skylight Room"

First Mrs. Parker would show you the double parlors. You would not dare to interrupt her description of their advantages and of the merits of the gentleman who had occupied them for eight years. Then you would manage to stammer forth the confession that you were neither a doctor nor a dentist. Mrs. Parker'e manner of receiving the admission was such that you could never afterward entertain the same feeling toward your parents, who neglected to train you up in one of the professions that fitted Mrs. Parker's parlors.

Next you ascended one flight of stairs and looked at the second-floor-back at 8 dollars. Convinced by her second-floor manner that it was worth the 12 dollars that Mr. Toosenberry always paid for it until he left to take charge of his brother's orange plantation in Florida near Palm Beach, where Mrs. Mclntyre always spent the winters that had the double front room with private bath, you managed to babble that you wanted something still cheaper.

If you survived Mrs. Parker's scorn, you were taken to look at Mr. Skidder's large hall-room on the third floor. Mr. Skidder's room was not vacant. He wrote plays and smoked cigarettes in it all day long. But every room-hunter was made to visit his room to admire the lambrequins. After each visit, Mr. Skidder, from the fright caused by possible eviction, would pay something on his rent.

Then-oh, then-if you still stood on one foot, with your hot hand clutching the three moist dollars in your pocket, and hoarsely proclaimed your hideous and culpable poverty, nevermore would Mrs. Parker be cicerone1 of yours. She would honk loudly the word "Clara", she would show you her back, and march downstairs. Then Clara, the colored maid, would escort you up the carpeted ladder that served for the fourth flight, and show you the Skylight Room. It occupied 7 by 8 feet of floor space in the middle of the hall. On each side of it was a dark lumber closet or store-room.

In it was an iron cot, a washstand and a chair. A shelf was the dresser. Its four bare walls seemed to close in upon you like the sides of a coffin. Your hand crept to your throat, you gasped, you looked up as from a well — and breathed once more. Through the glass of the little skylight you saw a square of blue infinity.

"Two dollars, suh," Clara would say in her half-contemptuous, half-Tuskegeenial tones. <

1 one who acts as a guide to local curiosities ■268

1 one who acts as a guide to local curiosities ■268

JACK LONDON

(1876—1916)

Jack London, one of the greatest American novelists and short story writers, was born in San-Francisco, California, the illegitimate son of an Irishman, a professor astrologer W. A. Channy. Eight months after Jack's birth his mother married John London, and they led a precarious existence running a grocery store and taking in boarders. London had no childhood and the pinch of poverty was chronic.

But he soon discovered the world of books. At ten he was borrowing books of adventure, travel and sea voyages from the public library. But as John London was often out of work, it became the task of eleven-year-old Jack to furnish food for the family. Odd jobs on newspaper routes, ice wagons, in canneries and jute mills gave him an intimate sympathy with working class life.

At sixteen he was an oyster pirate, travelled across the ocean as a sailor, and later tramped from San-Francisco to New York with an army of the unemployed. These hardships influenced his outlook,-and he learned two things, first that he would have to educate himself so that he could work with his brain; and second that there was something wrong with the economic system of the United States. He took an interest in the Labour movement and socialist literature. On reading the Communist Manifesto London became an enthusiastic believer in socialism. He was utterly convinced by Marx's reasoning, and joined the Socialist Party.

Deciding to live "by his brain" he entered the freshmen class of Oakland High School at nineteen.

He began attending working-men meetings in the City Hall Park, and was jailed for an attack on capitalism. London was labelled "The Boy Socialist" by the Oakland papers.. By cramming nineteen hours a day he managed to enter the university of California, but left before the year was up to support his mother and fosterfather by working in a laundry.

When gold was discovered in Alaska in 1896 Jack caught the universal fever. He returned without having mined an ounce of gold, but with experience which he later brilliantly transmitted in his famous collections of Northern Stories.

John London had died in his absence, and Jack returned to day labour until the acceptance of his first stories in 1899 encouraged him to devote his time to writing. He felt that in order to become a writer there were two things he had to acquire: knowledge and skill in writing. His reading continued: Kipling and Stevenson were his literary gods. His four intellectual grandparents were Darwin, Spencer, Marx and Nietzsche. His beliefs were a mixture of socialism. Nietzsche's doctrine of the superman,

Spencer's materialistic determination and Darwin's evolution theory.

In the course of three years (1900—1902) London published his collections of Northern Stories and the novel "A Daughter of the Snows" (1902).

In 1904 London published his novel "The Sea-Wolf", in which he dethrones the cult of "individualism", so popular in the reactionary philosophy of his time.

London's restless nature was longing for adventure and wild life. In January, 1904 he sailed on a steamship to report the Russian-Japanese war. Besides he gathered material in the poverty-stricken London East-End for "The People of the Abyss" (1903). The writer drew a realistic canvas of the misery and suffering of the poor people who lived in wretched slums of the capital.

The author's words ring with indignation when he speaks of the inhuman exploitation and the hard conditions of labour of the English workers. But London failed to see, and to show in the book that the only way out of this dead-lock was an organized struggle of the proletariat for their rights. The Russian revolution in 1905 greatly influenced London and made him change his views in many respects and led him to a better Understanding of class struggle. His new outlook was expressed in his books "The War of the Classes" (1905) and "Revolution and other Essays" (1910), The years 1905—1910 were' the highest point of his political activity.

In 1905 he went on a lecture tour of the country, and made a voyage to the Hawaii. On the deck of his yacht the "Snark" Jack London began writing "Martin Eden", perhaps the finest novel he ever wrote, and one of the greatest of all American novels.

The years of 1906—1911 were the prime of London's creative work. He wrote some of his best works: "The White Fang" (1906), "The Iron Heel" (1907) and "Martin Eden" (1909).

His book "The Iron Heel" marks the culminating point of his career as a revolutionary. In this work he treats the problems of revolution, and those of the individual and society dealing with the historical events in the USA at the beginning of the XX century. It is a remarkable anticipation of fascism. However, London never realized the great creative power of the masses; nor could he connect the individual with the masses — the only force which could help him to win his struggle against bourgeois society. His work shows both his strength and his weakness; for although he was a fighter, a revolutionist in life and art, he never succeeded in freeing himself completely from the influence of bourgeois culture.

After 1909 London gradually drifted away from the workers' labour movement.

By 1913 he was called highest paid, best-known, and most popular writer in the world, with books translated into eleven languages. But overwork, financial difficulties and heavy drinking

caused his literary output to deteriorate. He fell under the influence of bourgeois ideas and his new works "The Valley of the Moon" (1914) and "The Little Lady of the Big House" (1916) breathe a compromise with the capitalist system. Shortly before his death London resigned from the Socialist Party which, as he wrote, had betrayed the interests of the working class and sold itself to the ruling classes.

Although the cause of London's death was given out as an incurable disease, he, like his autobiographical hero Martin Eden, had taken refuge in suicide. During 16 years of his literary career, London published about 50 books: short stories, novels, essays. London's work is very unequal. He expresses widely differing, even antagonistic views of life. Good and bad stories are to be met side by side.

But it is an indisputable fact that London is one of the most popular writers in the world. His realism is characterized by sympathy and love for man in his struggle for life. It is his realism and humanism that keep his writings as living and fresh today as they were at the beginning of the century.

Northern Stories

During the gold rush in the Klondike Jack London gathered enormous material which he later used in his famous collections of Northern Stories: "The Son of the Wolf" (1900), "The God'of His Father's" (1901), "Children of the Frost" (1902); long stones "An Odyssey of the North" (1899), "The Call of the Wild" (1903), "White Fang" (1906).

Existence in the North was not easy, but London had an artist's eye and its loveliness sank into his soul forever:

... The whole long day was a blaze of sunshine. The ghostly winter silence had given way to the great spring murmur of awaking life. This murmur arose from all the land, fraught with the joy of living. It came from the things that lived. and moved again, things which had been as dead and which had not moved during the long months of frost. The sap was rising in the pines. The willows and aspens were bursting out in young buds..

The stories of these series are permeated with a firm belief in the noble aspiration of the common man, they bubble over with.life, passion and indomitable will for existence.

London's well-known long story "The Call of the Wild" is a story of a huge dog Buck, who remained faithful to his love of man until the call of the forest drew him back to primitive life.

"White Fang" is its sequel telling of how White Fang, instead of going from civilization back to the call of the primitive, comes

out of the wilds to live with men. J. London's, animal stories are very moving and interesting, though he erroneously applies the laws of nature to social life.

In his Northern Stories he uses the current slang of the mining camps, his style has freshness and strength. London's stories are imbued with the poetry and mystery of the Great North. The dominant note is tragedy, as it always is where men battle with the elemental forces of nature.

In the story "The Law of Life", London says: "To Life she (Nature) set one task, gave one law. To perpetuate was the task of life, its law was death." This task and law are clearly seen in the story "The White Silence", in which, although Mason is crushed by Nature, his son, soon to be born, will live. Jack London is not pessimistic in this story, nor in any of his works. Man may lose his life in the struggle with Nature, but life goes on, and Man, by the strength of his body and will is, in the end, the conqueror of Nature.

In her "Reminiscences of Lenin" Krupskaya tells us that two" days before Lenin's death she had read to him London's story "Love of Life": a man left in need by his comrades, faint with illness and hunger, makes his way through the cold and the snow to a large river where there are people, food and life. The story is striking in its severe realism, in its exposure of the cruel laws of capitalism which make the stronger man desert his comrade because he is ill and weak. Lenin thought much of the story, and this' is the highest appreciation of Jack London as a writer.

"Martin Eden" (1909). In his autobiographical novel London tells of his own struggles to overcome his lack of book-learning, to turn himself from a rough sailor into a cultivated man and a successful author in the period of three years. But this book is not simply a biography, it is a social novel as well, in which London draws a wide realistic picture of contemporary "high class society".

The main characters are Martin Eden, Ruth Morse and her family, and the poet Brissenden. Martin helps Ruth's brother out of an unpleasant row, and is invited to a dinner party at the Morses. Ruth, a pale etherial creature with spiritual blue eyes and a wealth of golden hair lends wings to his imagination. He feels that there is something to live for, to win to, to fight for. Martin's roughness frightens Ruth, and at the same time it is strangely pleasant to be so adored.

Martin has taken care of himself since he was eleven, and has had no opportunity to attend school. But now he decides to educate himself to prove to be worthy of Ruth. Several months go by, during' which Martin Eden studies grammar, reviews books on etiquette and reads books that catch his fancy.

His swift development is a source of surprise and interest for Ruth. She gradually realizes that she is in love with Martin. But

her parents have other plans for Ruth — they want her to marry some man in her own station of life. Finally they accept Ruth's and Martin's engagement, but no announcement is-made until Martin gets a suitable position.

But Martin's every spare moment is devoted to study, and then comes the great idea — he will write. That is a career and the way to win Ruth! He sets to work, toils on from early morning till dark, and mails the manuscripts to various magazines. But they are returned to him with tactfully worded rejection slips.

He struggles in the dark without advice, without encouragement, for Ruth has little faith in his power as a writer. But as his desire for fame is largely for Ruth's sake, he continues sending his stories to various magazines. Some months after his endless efforts a newspaper accepts two of his stories. But soon success again leaves him, and he is painfully conscious of the fact that Ruth and her family do not approve of what he is doing.

He reads his works to Ruth, but she cannot understand the flight of his mind. Although she is a Bachelor of Arts, he has gone far beyond her limitations. "Why don't you try to get work on a newspaper if you are so bound up in your writing?" is her constant urge.

Once at the Oakland Socialists' meeting Martin attacks their doctrines. But a young reporter impressed by the urgent need for sensation publishes an article pointing out that Martin is an ardent socialist and the black sheep of the family.

Now the Morses take a firm stand and demand that the engagement be broken, and Ruth agrees that they are not made for each other. It is a terrible shock to Martin. He feels quite alone in a hostile world with no one to help him, no one to believe in what he is doing.

He abandons the fight and stops writing, but goes on sending his manuscripts to different magazines and newspapers. They start a round to the publishers, and soon one by one are accepted.

There is no explaining of this sudden acception, it seems to be merely incidental. Money and fame pour in on Martin, but it means little to him now. His mind is dead to impressions. He feels mentally sick, and resolves he will never write again.

Martin thinks there is no cure for him except to get away to the South Seas, But on the verge of departure he feels that it is useless. The only thing he wants is rest, and finally he comes to a conclusion that only death will give him peace, will soothe him away to everlasting sleep.

Brissenden's words have become prophetic. The poet had warned Martin that the only thing to do was to tie himself to socialism or when success came he would have nothing to hold him to life. Martin renounces socialism, and then, sated with success, drowns himself.

IS 988. 273

The life of the talented writer lost in his philosophical search ruined by the bourgeois surroundings ends tragically. Eden's tragedy is the tragedy of an individual isolated from his people and his class. This defeat of Martin Eden reflects the weakness of the author himself who could find for his hero no better way out of the social contradictions of capitalist society.

Art Extract from "Martin Eden"

Once in his rooms, he dropped into a Morris chair and sat staring straight before him. He did not doze. Nor did he think. His mind was a blank, save for the intervals when unsummoned memory pictures took form and color and radiance just under his: eyelids. He saw these pictures, but he was scarcely conscious of them — no more so than if they had been dreams.

A knock at the door aroused him. He was not asleep, and his mind immediately connected the knock with a telegram, or letter, or perhaps one of the servants bringing back clean clothes from the laundry. He was thinking about Joe and wondering where he was, as he said, "Come in."

A knock at the door aroused him. He was not asleep, and his mind immediately connected the knock with a telegram, or letter, or perhaps one of the servants bringing back clean clothes from the laundry. He was thinking about Joe and wondering where he was, as he said, "Come in."

"Ruth!" he said, amazed and bewildered.

Her face was white and strained. She stood just inside the door, one hand against it for support, the other pressed to her side. She extended both hands toward him piteously, and started forward to meet him. As he caught her hands and led her to the Morris chair he noticed how cold they were. He drew up another chair and sat down on the broad arm of it. He was too confused to speak. In his own mind his affair with Ruth was closed and sealed.. Sevaral times he was about to speak, and each time he hesitated.

"No one knows I am here," Ruth said in a faint voice; with an appealing smile.

"What did you say?" he asked.

He was surprised at the sound of his own voice.

She repeated her words.

"Oh," he said, then wondered what more he could possibly say.

"I slipped in. Nobody knows I am here. I wanted to see you.. 1 came to tell you I have been very foolish. I came because I could no longer stay away, because my heart compelled me to come, because... because I wanted to come."

"I slipped in. Nobody knows I am here. I wanted to see you.. 1 came to tell you I have been very foolish. I came because I could no longer stay away, because my heart compelled me to come, because... because I wanted to come."

She came forward, out of her chair and over to him. She rested her hand on his shoulder a moment, breathing quickly, and then slipped into his arms. And in his large, easy way, desirous of. not inflicting hurt, knowing that to repulse this offer of herself was to inflict the most grievous hurt a woman could receive, he folded his arms around her and held her close. But there was no warmth in the embrace, no caress in the contact..

"What makes you tremble so?" he asked. "Is it a chill? Shall I light the grate?1'

He made a movement to disengage himself, but she clung more closely to him, shivering violently.

"It is merely nervousness," she said, with chattering teeth. "I'll control myself in a minute. There, I am better already."

Slowly her shivering died away. He continued to hold her, but he was no longer puzzled. He knew now for what she had come.

"My mother wanted me to marry Charley Hapgood," she announced.

"Charley Hapgood, that fellow who speaks always in platitudes?" Martin groaned. Then he added, "And now, I suppose, your mother wants you to marry me."

He did not put in the form of a question. He stated it as a certitude, and before his eyes began to dance the rows of figures of his royalties,

"She will not object, I know that much," Ruth said.

"She considers me quite eligible?"

Ruth nodded.

"And yet I am not a bit more eligible now than I was when she broke our engagement," he mediated. "I haven't changed any. I'm the same Martin Eden, though for that matter I'm a bit worse — I smoke now.

I am not changed. I haven't got a job. I'm not looking for a job. Furthermore, I am not going to look for a job.' And I still believe that Herbert Spencer is a great and noble man and that Judge Blount is an unmitigated ass. I had dinner with him the other night, so I ought to know."

"But you didn't accept father's invitation," she chided.

"So you know about that? Who sent him? Your mother?"

She remained silent.

"Then she did send him. I thought so. And now I suppose she has sent you?"

"No one knows that I am here," she protested. "Do you think my mother would permit this?"1

"She'd permit you to marry me, that's certain."

She gave a sharp cry. "Oh, Martin, don't be cruel. You have not kissed me once. You are as unresponsive as a stone. And think what I have dared to do!" She looked about her with a shiver, though half the look was curiosity. "Just think of where I am."

is* 275

"I could die for you! I could die for you!" Lizzie's words were ringing in his ears.

"Why didn't you dare it before?" he asked harshly. "When I hadn't a job? When I was starving? When I was just as I am now, as a man, as an artist, the same Martin Eden? That's the question I've been propounding to myself for many a day — not concerning you merely, but concerning everybody. I have not developed any new strength nor virtue. My brain is the same old brain. I haven't made even one new generalization on literature or philosophy. I am personally of the same value that I was when nobody wanted me. And what is puzzling me is why they want me now. Surely they don't want me for myself, for myself is the same oid self they did not want. Then they must want me for something else, for something that is outside of me, for something' that is not I! Shall I tell you what that something is? It is for the recognition I have received. That recognition is not I. It resides in the minds of others. Then again for the money. I have earned and am earning. But that money is not I. It resides in banks and in the pockets of Tom, Dick, and Harry. And is it for that, for the recognition and the money,

1 twain — 2; here: two fathoms deep; a fathom— a measure of depth (= six feet)

1 twain — 2; here: two fathoms deep; a fathom— a measure of depth (= six feet) ' a list of candidates put forward by the independents, i. e., by those who do not belong to any party

' a list of candidates put forward by the independents, i. e., by those who do not belong to any party I got to picking up papers apprehensively — much as one would lift a desired blanket which he had some idea might have a rattlesnake under it. One day this met my eye: —

I got to picking up papers apprehensively — much as one would lift a desired blanket which he had some idea might have a rattlesnake under it. One day this met my eye: — 1 I. P. — the Infamous Perjurer, M. T. *— the Montana Thief, B. S. — the

1 I. P. — the Infamous Perjurer, M. T. *— the Montana Thief, B. S. — the (1897), "The Awkward Age" (1899), "The Ambassadors" (1903) and "The Golden Bowl" (1904).'At the end of his life he wrote chiefly stories and essays on the craft of fiction. He died in London at the age of 73.

(1897), "The Awkward Age" (1899), "The Ambassadors" (1903) and "The Golden Bowl" (1904).'At the end of his life he wrote chiefly stories and essays on the craft of fiction. He died in London at the age of 73. 1 environment 262

1 environment 262 1 poor

1 poor 1 elevated, refined; here — of high rank

1 elevated, refined; here — of high rank 1 a bank officer who receives and counts money paid in; and pays money out on checks

1 a bank officer who receives and counts money paid in; and pays money out on checks the common mode of expression in a locality or in a profession

the common mode of expression in a locality or in a profession 1 one who acts as a guide to local curiosities ■268

1 one who acts as a guide to local curiosities ■268 A knock at the door aroused him. He was not asleep, and his mind immediately connected the knock with a telegram, or letter, or perhaps one of the servants bringing back clean clothes from the laundry. He was thinking about Joe and wondering where he was, as he said, "Come in."

A knock at the door aroused him. He was not asleep, and his mind immediately connected the knock with a telegram, or letter, or perhaps one of the servants bringing back clean clothes from the laundry. He was thinking about Joe and wondering where he was, as he said, "Come in." "I slipped in. Nobody knows I am here. I wanted to see you.. 1 came to tell you I have been very foolish. I came because I could no longer stay away, because my heart compelled me to come, because... because I wanted to come."

"I slipped in. Nobody knows I am here. I wanted to see you.. 1 came to tell you I have been very foolish. I came because I could no longer stay away, because my heart compelled me to come, because... because I wanted to come."