Своеобразие русской архитектуры: Основной материал – дерево – быстрота постройки, но недолговечность и необходимость деления...

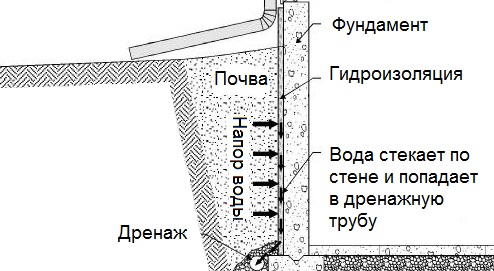

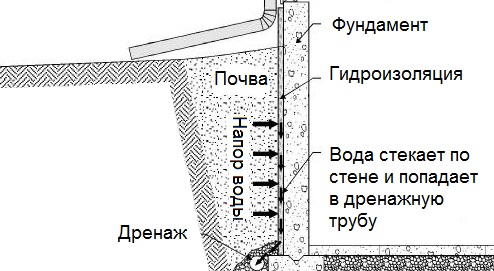

Общие условия выбора системы дренажа: Система дренажа выбирается в зависимости от характера защищаемого...

Своеобразие русской архитектуры: Основной материал – дерево – быстрота постройки, но недолговечность и необходимость деления...

Общие условия выбора системы дренажа: Система дренажа выбирается в зависимости от характера защищаемого...

Топ:

Организация стока поверхностных вод: Наибольшее количество влаги на земном шаре испаряется с поверхности морей и океанов...

Методика измерений сопротивления растеканию тока анодного заземления: Анодный заземлитель (анод) – проводник, погруженный в электролитическую среду (грунт, раствор электролита) и подключенный к положительному...

Теоретическая значимость работы: Описание теоретической значимости (ценности) результатов исследования должно присутствовать во введении...

Интересное:

Влияние предпринимательской среды на эффективное функционирование предприятия: Предпринимательская среда – это совокупность внешних и внутренних факторов, оказывающих влияние на функционирование фирмы...

Как мы говорим и как мы слушаем: общение можно сравнить с огромным зонтиком, под которым скрыто все...

Отражение на счетах бухгалтерского учета процесса приобретения: Процесс заготовления представляет систему экономических событий, включающих приобретение организацией у поставщиков сырья...

Дисциплины:

|

из

5.00

|

Заказать работу |

|

|

|

|

МИНСК 2011

Рекомендовано к изданию

Научно-методическим советом МИТСО

протокол № 1 от 12.01.2011

Авторы-составители:

Воробьева Т.А., Перевалова А.Е., доценты кафедры иностранных языков МИТСО, Лобач Л.Н., Холодинская И.И., старшие преподаватели кафедры иностранных языков МИТСО

Рецензенты:

Котенко Е.В., кандидат филологических наук, доцент кафедры белорусского и иностранных языков УО «Академия МВД Республики Беларусь»

Титовец Т.Е., кандидат педагогических наук, доцент, заведующая сектором методологии и теории педагогического образования Центра развития педагогического образования БГПУ им. М. Танка

| Studying Legal English: учебное пособие (в двух частях). Часть 1 / авт.-сост.: Воробьева Т.А., Перевалова А.Е., Лобач Л.Н., Холодинская И.И. – Мн.: МИТСО, 2011. – 155 с. Первая часть пособия состоит из 8 разделов, содержащих профессионально ориентированные материалы по следующей тематике: «Право и юриспруденция», «Римское право», «Международное право, его источники, субъекты», «ООН», «Европейский союз и его право». Адресовано студентам юридической специальности дневной формы обучения МИТСО, а также специалистам, изучающим английский язык для применения в правовой сфере деятельности.

| ||

|

| © Воробьева Т.А., Перевалова А.Е., Лобач Л.Н., Холодинская И.И., авт.-сост., 2011 © МИТСО, 2011 | |

ОГЛАВЛЕНИЕ

ПРЕДИСЛОВИЕ.. 6

UNIT 1: LAW & JURISPRUDENCE.. 7

TEXT 1. HISTORY OF LAW... 7

TEXT 2. JURISPRUDENCE.. 9

TEXT 3. CIVIL LAW... 10

UNIT 2: ROMAN LAW... 12

TEXT 1. ANCIENT ROMAN LAW... 12

TEXT 2. ROMAN LAW... 14

TEXT 3. THE LAW OF JUSTINIAN.. 18

TEXT 4. ROMAN FAMILY.. 20

TEXT 5. ROMAN LAW: CORPORATIONS. 22

TEXT 6. ROMAN LAW: THE LAW OF PROPERTY AND POSSESSION.. 23

TEXT 7. ROMAN LAW: DELICT AND CONTRACT.. 25

TEXT 8. Roman LaW: The law of succession.. 27

UNIT 3: INTERNATIONAL LAW... 32

TEXT 1. INTERNATIONAL LAW: AN OVERVIEW... 32

|

|

TEXT 2. INTERNATIONAL LAW AND MUNICIPAL LAW... 35

TEXT 3. INTERNATIONAL LAW (INTERNATIONAL PUBLIC LAW & INTERNATIONAL PRIVATE LAW) 37

TEXT 4. CONFLICT OF LAWS. 40

TEXT 5. THE STAGES IN A CONFLICT CASE.. 41

TEXT 6. CHOICE OF LAW RULES. 42

UNIT 4: THE SOURCES OF INTERNATIONAL LAW... 43

TEXT 1. THE SOURCES OF INTERNATIONAL LAW... 43

TEXT 2. THE SOURCES OF INTERNATIONAL LAW – THE PLACE OF TREATIES. 46

UNIT 5: THE SUBJECTS OF INTERNATIONAL LAW... 51

TEXT 1. SUBJECTS OF INTERNATIONAL LAW... 51

TEXT 2. THE HOLY SEE.. 52

TEXT 3. INTERGOVERNMENTAL ORGANIZATIONS (IGOS). 54

UNIT 6: THE UNITED NATIONS ORGANIZATION.. 58

TEXT 1. THE UNITED NATIONS ORGANIATION (UNO): OVERVIEW... 58

TEXT 2. GENERAL ASSEMBLY.. 60

TEXT 3. SECURITY COUNCIL.. 62

TEXT 4. ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COUNCIL AND The un Secretariat.. 63

TEXT 5. TRUSTEESHIP COUNCIL.. 66

TEXT 6. INTERNATIONAL COURT OF JUSTICE: AN OVERVIEW... 67

TEXT 7. INTERNATIONAL COURT OF JUSTICE: HOW THE COURT WORKS. 68

UNIT 7: EUROPEAN UNION.. 73

TEXT 1. EU INSTITUTIONS AND OTHER BODIES. 75

TEXT 2. The European Parliament.. 77

TEXT 3. The Council of the European Union.. 80

TEXT 4. THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION.. 86

TEXT 5. THE EUROPEAN COUNCIL - AN OFFICIAL INSTITUTION OF THE EU.. 90

TEXT 6. THE COURT OF JUSTICE.. 92

TEXT 7. The European Court of Auditors. 95

TEXT 8. THE EUROPEAN CENTRAL BANK.. 96

TEXT 9. THE EUROPEAN ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMITTEE.. 98

TEXT 10. THE COMMITTEE OF THE REGIONS. 99

TEXT 11. The European Investment Bank.. 101

TEXT 12. THE EUROPEAN INVESTMENT FUND.. 103

TEXT 13. THE EUROPEAN OMBUDSMAN.. 103

TEXT 14. THE EUROPEAN DATA PROTECTION SUPERVISOR.. 104

TEXT 15. INTERINSTITUTIONAL BODIES. 106

TEXT 16. SPECIALISED EU AGENCIES. 106

TEXT 17. THE HISTORY OF EUROJUST.. 112

UNIT 8: EUROPIAN UNION LAW... 113

TEXT 1. LEGISLATION AND TREATIES. 113

TEXT 2. WHAT IS EU LAW?. 114

TEXT 3. TREATIES. 115

TEXT 4. JUSTICE, FREEDOM AND SECURITY.. 117

TEXT 5. DECISION-MAKING IN THE EUROPEAN UNION.. 121

TEXT 6. EUR-Lex: PROCESS AND PLAYERS. 123

APPLICATION 1. LINKING WORDS. 147

APPLICATION 2. THE PLAN FOR WRITING ABSTRACTS OF THE TEXT 151

BIBLIOGRAPHY.. 155

ПРЕДИСЛОВИЕ

Совершенствование навыков реферирования представляет собой способ формирования профессиональной компетентности студентов-правоведов.

Реферирование – творческий процесс, включающий осмысление первичного, авторского текста, преобразование информации и создание вторичного, производного, собственного текста.

Организация самостоятельной работы студентов является обязательным компонентом учебного процесса в системе высшего образования Республики Беларусь. Под самостоятельной работой понимается как внеаудиторная работа, так и работа в аудитории под контролем преподавателя.

Данный вид работы направлен на решение следующих задач:

- закрепление, обобщение и повторение пройденного учебного материала;

|

|

- применение полученных знаний в стандартных ситуациях и при решении задач высокого уровня сложности и неопределенности;

- формирование готовности студентов к самообразованию в течение всей жизни.

Данное пособие представляет собой комплекс текстов по различным аспектам, касающимся права и юридической системы европейских стран в целом.

Пособие состоит из двух частей, содержание которых составляют современные профессионально ориентированные материалы. Каждая из частей содержит набор слов и выражений, необходимых для реферирования текста, а также примерный план анализа текста. В первую часть включены материалы по следующим темам: «Право и юриспруденция», «Римское право», «Международное право, его источники, субъекты», «Организация Объединённых Наций», «Европейский союз и его право».

Тематическое наполнение пособия обусловлено учебным планом по специальности «Международное право». Текстовый материал, подобранный из оригинальных источников (книг, Интернет-ресурсов), способствует повышению уровня владения студентами юридической лексикой и терминами, а также направлено на формирование профессиональной компетенции студентов.

Пособие способствует расширению и систематизации знаний у студентов, имеющих деловые связи в области права.

UNIT 1: LAW & JURISPRUDENCE

TEXT 1. HISTORY OF LAW

The history of law or legal history is the history of our race, and the personification of its experience. Law developed before history was even recorded and rules were recognized to reconcile discussions before written laws or courts ever existed. This dates back to the age of the ancient Egyptians and Babylonians. Different to idea, law was discovered and not invented. It was systematically discovered established on historical experiences and historical events of generations for years and centuries.

In Babylonia, the Mesopotamia region, ethnic customs were transformed into social laws thousands of years ago. Laws also existed in ancient Greece. Our information of ancient Greek laws comes from several Homeric writings. As well, the Roman law was the legal system not only in ancient Rome, but was applied all over Europe until the eighteenth century. A lot of European modern laws are still influenced by Roman law. English and North American common and civil laws also be obliged some debt to Roman ancient law.

Customary law dictated human actions, for a long time, by reflecting the conduct of people towards one another. Below customary law, rules spontaneously emerged and developed to establish an argument between people. These spontaneously born rules are voluntarily pursued by the parties implicated in the dispute and are more likely to be gratifying to the parties than a rule imposed on them by an authoritative body. The customary law was the procedure that guides to the discovery of natural law. Natural law is the irrefutable standard to which laws must be stable in order to be legitimate. In other words, we can say that natural law is the body of rules of right conduct and justice common to all people. By comparison, common law is a system by which a law comes to pass based on some legal antecedent.

|

|

Historically, Anglo-Saxon customary law implicated a group of people known as Bohr. The group compromised a guarantee for each of its members. Each individual would protect his/her property claims by accepting the responsibility to respect the property rights of others. The group would then pay the penalties for any member found to be in infringement of the agreement. Since finances were at stake, the group had an inducing reason to police its members and often invalidate the membership of those found in infringement of the rules. Moreover, it was also common to socially exile those who violate the rules. If the outcast member pays compensation, then they may be permitted to become members of the group again. These rules that evolved spontaneously established disputes between people in a civilized method thus eliminating violent measures. In some cases, the process implicated appeals and mutual disputes. This process and these two way arguments are analogous to financial organizations (in our time) such as insurance companies.

Early Anglo-Saxon courts were assemblies made up of common people and neighbours. These early courts passed their sentence according to customary law. This guaranteed non violent means for solving conflicts.

In the Middle Ages, there was a commercial and trade law that governed the trade and commercial transactions during Europe. This law emerged appropriate to require for certain standards to normalize international trade. Europe wide court systems and legal orders were formed and those who did not abide by the rules, regulations and decisions of this system were excluded from the social as well as business community. That is, the suffered the effect of not being able to conduct business transactions in the future.

Basically, customary law seeks to protect individual rights and during non violent resources. The economic fines imposed on the culpable party are destined to compensate the victim in the dispute. The culpable party is obliged to make payment in order to elude social and commercial exclusion. At the same time, the method permits space for every individual including the supposed guilty party to speak, dispute and express their difference.

Among certain lawyers and historians of legal method it has been seen as the registering of the progress of laws and the technical clarification of how these laws have developed with the view of better considerate the origins of diverse legal concepts, some consider it an area of intellectual history. Twentieth century historians have examined legal history in a more contextualized mode more in line with the thoughts of social historians. They have looked at legal institutions as complicated systems of rules, players and symbols and have seen these elements interrelate with society to change, adjust, oppose or promote certain characteristics of civil society. Such legal historians have tended to evaluate case histories from the parameters of social science investigation, using statistical methods, analyzing class differences among litigants, petitioners and other players in diverse legal processes. By analyzing case results, operation costs, number of settled cases they have begun an examination of legal institutions, practices, actions and briefs that give us a more composite picture of law and society than the study of jurisprudence, case law and civil codes can accomplish.

TEXT 2. JURISPRUDENCE

In the United States jurisprudence normally signifies the philosophy of law. Jurisprudence is the study and philosophy of law. Specialists of jurisprudence, or legal philosophers, expect to gain a deeper understanding of the nature of law, of legal analysis, legal systems and of legal institutions.

|

|

Legal philosophy has many characteristics, but three of them are the most common:

· Natural law is a school of legal philosophy which considers that there are invariable laws of nature which govern us, which are general to all human societies, and that our institutions should try to equal this natural law.

· Analytic jurisprudence is indicate to be an objective study of law in impartial conditions, distinguishing it from natural law, which evaluates legal systems and laws throughout the structure of natural law theory, asks questions like, "What is law?" "What are the criteria for legal validity?" or "What is the relationship between law and morality?" and other such questions that legal philosophers may compromise.

· Normative jurisprudence looks at the intention of legal systems, and which sorts of laws are adequate, asks what law ought to be. It overlaps with moral and political philosophy, and contains questions of whether one ought to follow the law, on what grounds law-breakers might correctly be punished, the correct uses and limits of regulation, how judges ought to decide cases.

The theory of jurisprudence has been around for fairly a long time. Both the Ancient Greeks and Romans believed the philosophy of law, and earlier societies possibly did as well. The word itself is resulting from a Latin phrase, juris prudentia, significance “ the study, knowledge, or science of law. ” As long as humans have had laws governing their activities, philosophers and commentators have been meditation about these laws and considering how they fit in with the societies which they are presumed to codify and protect.

Since law can frequently be slippery and incomprehensible, it may come as no revelation to learn that jurisprudence is exceptionally complicated and sometimes very confusing. Many of the world's most famous specialists and philosophers have at least dabbled in jurisprudence, elaborating dense tomes, complex arguments, and complicated expression. The study of jurisprudence is also essential for a good lawyer, because it guarantees that he or she deeply understands the law and the philosophical approaches which have been implicated in its conception.

Studying law does not automatically make someone a lawyer, even though it is a significant element of a legal education. For judges and other people who must infer, defend, or refuse the law, jurisprudence is a very important field of study, along with more general studies of history, society, and philosophy. Since laws are such an important emphasizing of society, jurisprudence can also offer important information about a nation and its people.

Modern jurisprudence and philosophy of law is influenced today principally by Western academics. The concepts of the Western legal tradition have become so enveloping all over the world that it is persuasive to see them as universal. Traditionally, however, many philosophers from other civilization have discussed the same questions, from Islamic scholars to the ancient Greeks.

TEXT 3. CIVIL LAW

Civil law, or European Continental law, or Romano-Germanic law, is the principal system of law in the world. Civil law is the legal tradition that derives from Roman law. The countries discovered in this category have drawn principally on their Roman legal inheritance in addition to other sources, and while giving anteriority to written law, have determinedly selected for a systematic codification of their ordinary law. Also found in this category are countries, usually of the mixed law diversity, that have not resorted to the method of codifying law but that have retained to varying degrees enough elements of Roman legal construction, " as a written reason ", to be considered associated to the civil tradition. On the other hand, there are countries in this category where Roman influence was feebler but whose law, codified or not, rests on the concept of legislated law which in many ways resembles the systems of countries with a "pure" civil tradition (for example, Scandinavian countries that maintenance a unique position within the "Romano-Germanic" family).

In civil law the sources recognized as authoritative are, principally, legislation – especially codifications in constitutions or statutes passed by government – and, secondarily, custom. In some civil law countries, the legal systems are established around one or various codes of law, which set out the most important principles that conduct the law. The most famous example is possibly the French Civil Code, even though the German Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch (or BGB) and the Swiss Civil Code are also landmark events in legal history. The civil law systems of Scotland and South Africa are without codifying, and the civil law systems of Scandinavian countries remain largely without codifying.

|

|

Civil-law systems vary from common-law systems in the substantive content of the law, the operative procedures of the law, legal terminology, the way in which authoritative sources of law are recognized, the institutional framework within which the law is applied, and the education and structure of the legal profession.

Scholars of comparative law and economists instigating the legal origins theory generally subdivide civil law into three different groups:

· French civil law: in France, the Benelux countries, Italy, Spain and former colonies of those countries;

· German civil law: in Germany, Austria, Croatia, Switzerland, Greece, Portugal, Turkey, Japan, South Korea and the Republic of China;

· Scandinavian civil law: in Denmark, Norway and Sweden. Finland and Iceland inherited the system from their neighbours.

Within the United States and its territories, only three jurisdictions are considered civil-law systems - Louisiana, Puerto Rico, and Guam - but because of the strong persuade of common law in these jurisdictions, they are truly “ mixed systems ” of civil and common law. Under the Supreme Court's ruling in Erie v. Tompkins (1938), Louisiana courts are the final authority on subjects concerning topics of civil law under the Louisiana Code of 1870. Similarly, courts in Puerto Rico and Guam have responsibility for the expansion of the civil law in those island jurisdictions.

Civil law is generally of tangential interest to the U.S. Supreme Court. The justices of the Supreme Court are results of the American common-law tradition, and, with few exceptions, they have not been familiar with civil-law sources or systems. Nevertheless, with the expansion of international private law, the increasing commercial significance of the European Union and Japan, and growing contacts among legal practitioners and legal elites across national limits, the Supreme Court will have to come to conditions with the civil law tradition, the most extended and significant legal tradition in the modern world.

UNIT 2: ROMAN LAW

TEXT 1. ANCIENT ROMAN LAW

As the empire developed, the emperor stood at the top of the administrative system. He served as military commander in chief, high priest, court of appeal, and source of law. All this power was intensely personal: Soldiers swore their oath to the emperor, not to a constitution or a flag. Personal ties of patronage, friendship, and marriage had always bound together Roman society, but during the empire the emperor became the universal patron.

Military loyalty, bureaucracy, and imperial succession were all viewed in personal terms. This concentration of power produced a court in which government officials and the imperial family competed with poets, astrologers, doctors, slaves, and actors for the emperor's attention and favour. The emperor's own slaves and freedmen dominated the clerical and financial posts and formed the core of imperial administration just as they did in the household administration of any Roman aristocrat. Deep ties of loyalty bound Roman freedmen and slaves to their patrons so that they faithfully served even the most monstrous emperors.

The emperors took over the Senate's political and legislative power, but they needed the help of senators who had experience in diplomacy, government, and military command. Since the emperor designated candidates for all government positions, senators had no other access to high office except through loyal service. A shrewd emperor could turn senatorial pride and loyalty to the advantage of the empire. By simply allowing senators to wear a broad purple stripe on their togas, for example, the emperor marked them as rulers of the Mediterranean and added to their prestige.

Only when emperors treated senators with contempt did the senators feel justified in conspiring against the emperor under the banner of freedom. Some ambitious senators dreamed of reaching supreme power and even of replacing the emperor. An occasional opportunity presented itself - Nero's death brought four senators to the imperial throne in the single year of AD 69.

However, most senators remained loyal to the emperor because the constant danger of displeasing suspicious emperors outweighed the remote chance of success. As the old noble families died out, the emperors found new blood among the local elite of Italy and the provinces. In the 2nd century AD more than half the senators were of provincial origin.

The emperor Augustus had first given the equestrian order increased responsibilities, and they continued to play an important role in the governance of the empire. Only a few of the equites actually worked for the emperor, some served as officers of Rome's auxiliary forces, and others as civil administrators.

Most members of this order remained in their home cities - there were 500 in the Spanish seaport of Cadiz alone - and formed the basis of a loyal elite that characterized the early empire. As the government expanded, the "equestrian career" began to resemble a modern civil service with ranks, promotions, and a salary scale. While retired centurions occasionally advanced into the equestrian order and equestrians into the Senate, social mobility remained limited.

The emperors tried to keep the equestrians loyal by permitting them signs of privilege similar to senators. Tens of thousands of equestrians across the empire marked their status by wearing togas with a narrow purple stripe and sitting in the front row at public games.

Senators and equestrians whom the emperor appointed as governors, generals, and prefects held substantial power in the provinces, although provincial administration was initially restricted to issues of taxation and law and order. The system grew increasingly complex, but it always remained rather small for such an expansive empire.

Twelfth-century China had an elite government official for every 15,000 subjects, as compared to Rome, which had one for every 400,000 people in the empire. Such figures are crude, but they show that Roman administration was less intrusive than its counterparts in China and many other modern states. The empire, with its limited administrative system, could not have functioned without local officials in the provinces or subject kings appointed by Rome, like Herod the Great in Judea.

Historians often focus on political leaders, but it is local grievances about high taxes, crime, or the price of bread that most often provoke people to revolt against a government. The Romans relied on civil laws to address a variety of these issues. Roman law in the republic was often based on custom. During the Roman Empire, however, the emperor became the final source of law.

People in the provinces were well aware that the emperor sat atop the chain of command as recorded in the New Testament to the Bible. In regard to taxation, for example, a passage in Luke 2:1 notes: "And it came to pass in those days, that a decree went out from Caesar Augustus, that the whole world should be enrolled to be taxed." However, popular anger over issues such as taxation was still directed toward the political officeholders who administered the laws.

Roman law was one of the most original products of the Roman mind. From the Law of the Twelve Tables, the first Roman code of law developed during the early republic, the Roman legal system was characterized by a formalism that lasted for more than 1,000 years. The basis for Roman law was the idea that the exact form, not the intention, of words or of actions produced legal consequences. To ignore intention may not seem fair from a modern perspective, but the Romans recognized that there are witnesses to actions and words, but not to intentions.

Roman civil law allowed great flexibility in adopting new ideas or extending legal principles in the complex environment of the empire. Without replacing older laws, the Romans developed alternative procedures that allowed greater fairness. For example, a Roman was entitled by law to make a will as he wished, but, if he did not leave his children at least 25 percent of his property, the magistrate would grant them an action to have the will declared invalid as an "irresponsible testament." Instead of simply changing the law to avoid confusion, the Romans preferred to humanize a rigid system by flexible adaptation.

Early Roman law derived from custom and statutes, but the emperor asserted his authority as the ultimate source of law. His edicts, judgments, administrative instructions, and responses to petitions were all collected with the comments of legal scholars. As one 3rd-century jurist said, "What pleases the emperor has the force of law." As the law and scholarly commentaries on it expanded, the need grew to codify and to regularize conflicting opinions. It was not until much later in the 6th century AD that the emperor Justinian I, who ruled over the Byzantine Empire in the east, began to publish a comprehensive code of laws, collectively known as the Corpus Juris Civilis, but more familiarly as the Justinian Code.

TEXT 2. ROMAN LAW

Part I

Roman law is the law of ancient Rome from the time of the founding of the city in 753 BC until the fall of the Western Empire in the 5th century AD. It remained in use in the Eastern, or Byzantine, Empire until 1453. As a legal system, Roman law has affected the development of law in most of Western civilization as well as in parts of the East. It forms the basis for the law codes of most countries of continental Europe and derivative systems elsewhere.

The term Roman law today often refers to more than the laws of Roman society. The legal institutions evolved by the Romans had influence on the laws of other peoples in times long after the disappearance of the Roman Empire and in countries that were never subject to Roman rule. To take the most striking example, in a large part of Germany, until the adoption of a common code for the whole empire in 1900, the Roman law was in force as “subsidiary law”; that is, it was applied unless excluded by contrary local provisions. This law, however, which was in force in parts of Europe long after the fall of the Roman Empire, was not the Roman law in its original form. Although its basis was indeed the Corpus Juris Civilis - the codifying legislation of the emperor Justinian I - this legislation had been interpreted, developed, and adapted to later conditions by generations of jurists from the 11th century onward and had received additions from non-Roman sources.

Development of the jus civile and jus gentium

In the great span of time during which the Roman Republic and Empire existed, there were many phases of legalistic development. During the period of the republic (753–31 BC), the jus civile (civil law) developed. Based on custom or legislation, it applied exclusively to Roman citizens. By the middle of the 3rd century BC, however, another type of law, jus gentium (law of nations), was developed by the Romans to be applied both to themselves and to foreigners. Jus gentium was not the result of legislation, but was, instead, a development of the magistrates and governors who were responsible for administering justice in cases in which foreigners were involved. The jus gentium became, to a large extent, part of the massive body of law that was applied by magistrates to citizens, as well as to foreigners, as a flexible alternative to jus civile.

Roman law, like other ancient systems, originally adopted the principle of personality - that is, that the law of the state applied only to its citizens. Foreigners had no rights and, unless protected by some treaty between their state and Rome, they could be seized like ownerless pieces of property by any Roman. But from early times there were treaties with foreign states guaranteeing mutual protection. Even in cases in which there was no treaty, the increasing commercial interests of Rome forced it to protect, by some form of justice, the foreigners who came within its borders. A magistrate could not simply apply Roman law because that was the privilege of citizens; even had there not been this difficulty, foreigners would probably have objected to the cumbersome formalism that characterized the early jus civile.

The law that the magistrates applied probably consisted of three elements: (1) an existing mercantile law that was used by the Mediterranean traders; (2) those institutions of the Roman law that, after being purged of their formalistic elements, could be applied universally to any litigant, Roman or foreigner; and (3) in the last resort, a magistrate’s own sense of what was fair and just. This system of jus gentium was also adopted when Rome began to acquire provinces so that provincial governors could administer justice to the peregrini (foreigners). This word came to mean not so much persons living under another government (of which, with the expansion of Roman power, there came to be fewer and fewer) as Roman subjects who were not citizens. In general, disputes between members of the same subject state were settled by that state’s own courts according to its own law, whereas disputes between provincials of different states or between provincials and Romans were resolved by the governor’s court applying jus gentium. By the 3rd century AD, when citizenship was extended throughout the empire, the practical differences between jus civile and jus gentium ceased to exist. Even before this, when a Roman lawyer said that a contract of sale was juris gentium, he meant that it was formed in the same way and had the same legal results whether the parties to it were citizens or not. This became the practical meaning of jus gentium. Because of the universality of its application, however, the idea was also linked with the theoretical notion that it was the law common to all peoples and was dictated by nature - an idea that the Romans took from Greek philosophy.

|

|

|

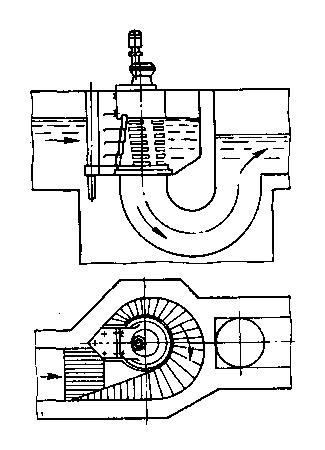

Состав сооружений: решетки и песколовки: Решетки – это первое устройство в схеме очистных сооружений. Они представляют...

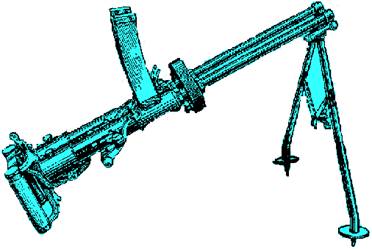

История развития пистолетов-пулеметов: Предпосылкой для возникновения пистолетов-пулеметов послужила давняя тенденция тяготения винтовок...

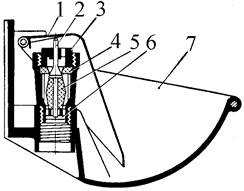

Индивидуальные и групповые автопоилки: для животных. Схемы и конструкции...

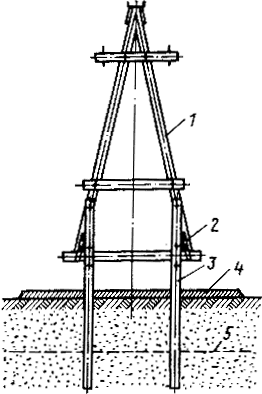

Особенности сооружения опор в сложных условиях: Сооружение ВЛ в районах с суровыми климатическими и тяжелыми геологическими условиями...

© cyberpedia.su 2017-2024 - Не является автором материалов. Исключительное право сохранено за автором текста.

Если вы не хотите, чтобы данный материал был у нас на сайте, перейдите по ссылке: Нарушение авторских прав. Мы поможем в написании вашей работы!