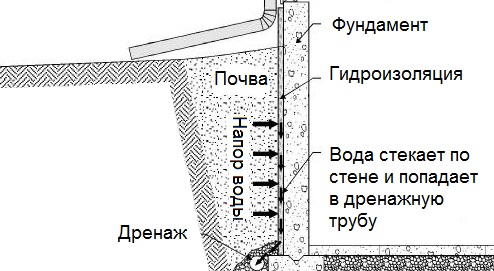

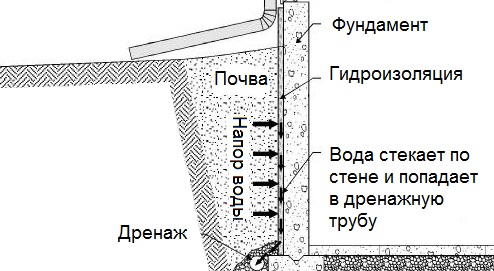

Общие условия выбора системы дренажа: Система дренажа выбирается в зависимости от характера защищаемого...

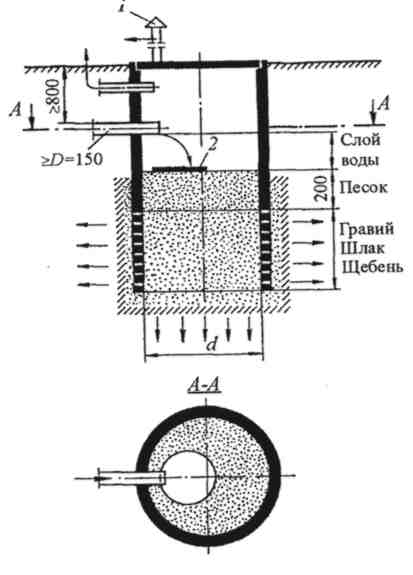

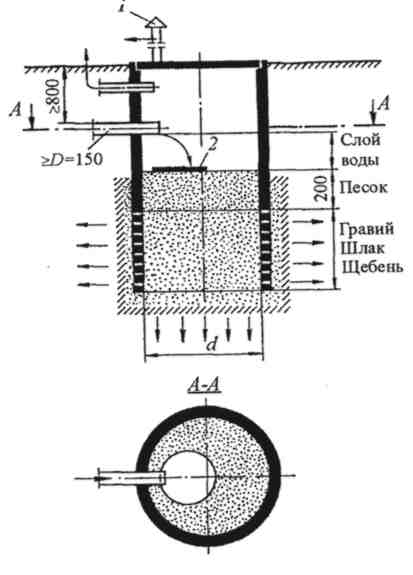

Индивидуальные очистные сооружения: К классу индивидуальных очистных сооружений относят сооружения, пропускная способность которых...

Общие условия выбора системы дренажа: Система дренажа выбирается в зависимости от характера защищаемого...

Индивидуальные очистные сооружения: К классу индивидуальных очистных сооружений относят сооружения, пропускная способность которых...

Топ:

Проблема типологии научных революций: Глобальные научные революции и типы научной рациональности...

Устройство и оснащение процедурного кабинета: Решающая роль в обеспечении правильного лечения пациентов отводится процедурной медсестре...

Характеристика АТП и сварочно-жестяницкого участка: Транспорт в настоящее время является одной из важнейших отраслей народного хозяйства...

Интересное:

Мероприятия для защиты от морозного пучения грунтов: Инженерная защита от морозного (криогенного) пучения грунтов необходима для легких малоэтажных зданий и других сооружений...

Искусственное повышение поверхности территории: Варианты искусственного повышения поверхности территории необходимо выбирать на основе анализа следующих характеристик защищаемой территории...

Как мы говорим и как мы слушаем: общение можно сравнить с огромным зонтиком, под которым скрыто все...

Дисциплины:

|

из

5.00

|

Заказать работу |

|

|

|

|

The preparation of a speech is very important, crucial that is why at this point we pay special to the structure of a speech. Now let us pass to the discussion of the structure suggested by the linguists R. Vicar and D. Arnold. Thus, R.Vicar contemplates that it must be focused on an audience response, be effective and meet all the requirements of an audience. He suggests that the steps are the following: choose the topic; select the main points; organize ideas into an interesting and understandable speech; develop the points of the speech; invent openings; create conclusions; choose words to use.

Indisputably, the initial step in preparing a persuasive speech is often the most difficult-selecting the topic. A speaker should focus his topic by identifying a goal. "Goal setting, wrote Stephen Covey, a professor of business management and author of Seven Habits of Highly Effective People, is obviously a powerful process.... Ifs a common denominator of successful individuals and organizations" [Vicar -1994].

There are three qualities that make an effective specific purpose. A good specific purpose is: "focused on an audience response; operationally defined; realistic".

At this point we would agree that it is a critical key to persuasive speech because the goal in speaking, the specific purpose, should always focus on what a speaker wants to accomplish with his audience.

An operationally denned specific purpose makes goal clear and objective. Using operational definitions, makes purposes explicit, and a speaker can objectively determine whether we achieved his stated objective.

The third quality of an effective specific purpose statement is that it must be realistic. While public speaking is a very powerful tool, it is not omnipotent.

The next step, according to R. Vicar is selecting the main points: "once you have selected a topic and identified a specific purpose for your audience, your next step is to determine the main points in the body of the speech. The average adult attention span is roughly fifteen minutes, so a speaker cannot count on covering twenty or thirty ideas with any hope of success. It is interesting to point out that we forget nearly 75 percent of what we hear, so a speaker cannot expect his audience to remember long lists of ideas" [Vicar -1994].

A presenter may recall a few important ideas, but do not recall everything he or she knew when took the final examination.

Organize the ideas is the following step:

"Humans are organizing creatures, due to this fact it is important to organize organizational patterns, the most useful for persuasive speech is the motivated sequence. Consequently, a speaker may wish to organize his speech by providing these steps: gain attention through an interesting anecdote or similar device; provide a clear picture of the need for taking action; offer a straightforward resolution of the need in the satisfaction step; use vivid and expressive depictions to help the listeners visualize the consequences of doing nothing or the benefits of accepting proposal; and finally, urge them to action".

|

|

R. Vicar suggests that once me main ideas of the speech have been selected and ordered, the next crucial way is consider ways to develop those ideas. To make a speech memorable, or to make the idea appealing, it is necessary to offer supporting material that impresses listeners.

Common forms of support include the following: "examples that illustrate a particular point; descriptions that create mental pictures of your ideas; testimony that cites the words of an expert or witness; numerical data that quantify the concept; audio or visual aids that help your audience hear or see the material more clearly” [Vicar -1994].

A good rule of thumb, writes D. Arnold is to “tell your audience what you are going to say, say it, then tell the audience what you have said” [Vicar – 1994]. Try to develop your key points in an interesting and varied way, drawing on relevant examples, figures etc.

"The application of numerical data and audiovisual aids is another type of supporting material", - said R. Vicar. There is no need to say that we live in an age of numbers, and quantifying ideas can make them more understandable. Most visual aids are used to clarify the meaning of verbal discourse.

Having structured and developed the main ideas of a talk, the next task is to devise an introduction. The introduction is critical. It must grab the attention of an audience and establish rapport, a feeling of unity, with a speaker. Common opening means include humorous anecdotes, rhetorical questions, and startling statements that grab the audience's attention.

Taking everything into account it may be said any composition, including a speech has a beginning, middle and an end. Thus, the traditional and generally accepted structure of a speech (according to R. Vicar) contains the following elements:

• Introduction, in which the speaker grabs the attention of the audience, introduces the subject, his purpose and himself to the audience;

• The body of the speech, which contains the outline of the major ideas and information that supports and clarifies the ideas;

• Conclusion (close), which contains a summary or a conclusion from the information presented and which helps the speaker to end his speech gracefully.

Basically, the conclusion of any speech is very important, because it consolidates all the information presented and reinforces the speeches purposes. The strategy of the conclusion may be fairly varied and depends on the duration of the speech and its complexity.

Above all it is important that the speaker should finish confidently, the audience should be conscious that he is going to close. Such closing words as "Well, that’s all I have to say..." or "I guess, I will stop..." should be avoided. They are too straightforward. It is better to stop without - talking about stopping. Anecdotes, jokes, quotations, rhetorical questions are good ways to end.

Thus, having covered the schemes of writing of convincing speech, proposed by R. Vicar and D. Arnold we believe that it is a time to suggest you our own plan of an effective speech. It goes without saying that we agree with some aspects in the classification of Vicar, for example that the traditional and generally accepted structure of a speech contains the following elements: introduction, the body of the speech, conclusion. But we do not agree with the order of writing, and some certain elements which fall out but are very crucial and significant for a memorable and persuasive speech.

|

|

On top of that, to make an effective body of a speech a speaker should use various forms of support:

a) Employing Audiovisual Aids - as it was suggested by R. Vicar - here we follow his stand because photographs, slides, graphs, recordings, audiotapes, videotapes, and models all offer sights and sounds that can reinforce speakers words;

b) Such elements as ethos - refers to the moral sphere: a speaker influences an audience because they trust him and his judgment; logos - consists in persuading the audience by being reasonable and referring to the believable facts; pathos - consists in persuading an audience by emotional arguments are an integral elements in a speech; all these elements have to be combined not to be primitive and straightforward;

c) Special attention should be paid to the style and the language of a speech, lexical and especially to the syntactical expressive means and stylistic devices; And in order to keep the listeners attention different kinds of repetitions have to be applied in order to increase the expressiveness.

d) The next crucial step is to discover the goals, motives and expectations of the audience, to establish contact with an audience. Body can be described as planning which is an indispensable stage in effective public speaking. And in order to keep the listeners attention different kinds of repetitions, definitions, examples, numerical data, citations, quotations have to be applied.

To be an effective public speaker, he must understand public opinion, why people have opinions, and how to affect those opinions. This gives rise to the view that a presenter is to bear in mind the idea of relating to people most effectively and build his own personal style.

Lecture 10.

The colloquial sphere.

The questions are based on Y.M. Skrebnev’s “Fundamentals of English Stylistics”, 2000.

Lecture 11.

Decoding stylistics.

The stylistics has its own technique of interpretation of the text and the aim of it is the identification of the stylistic effects appearing in the text, their depiction and elucidation from the point of view of the dependence on the message. Such stylistic method of deciphering the text is called the decoding stylistics.

The development of the text theory that we observe nowadays testifies a great interest to text as an object of linguistic research. This multifarious interest to text studying can be explained by the following: to study the text means to study its creator, i.e. personality, for any text is a product of its sender’s mind, his way of thinking. This view has been well propounded by Russian Decoding Stylistic School represented by such well-known linguists as M. Riffaterre, I.V. Arnold, V.A. Kuharenko, etc. As the term suggests “the focus is on the receiving end, on decoding and the addressee’s response” [Arnold – 1990].

This approach to text interpretation stems from the works of Russian linguists L.V. Scherba, M.M. Bakhtin, V.V. Vinogradov, B. Tomashevsky, R. Jakobson, B.A. Larin and others.

According to Hornby’s Oxford Student’s Dictionary of Current English the verb “to decode” is classified as “to decipher a code” [Hornby – 1984].

Decoding stylistics is the latest trend in stylistic analysis that makes use of theoretical findings in such areas of science as information theory, psychology, statistical studies in combination with linguistics, literary theory, history of art, literary criticism, etc. [Znamenskaya – 2004]

|

|

The term “decoding stylistics” came from the application of the theory of information to linguistics by such authors as M. Riffatrre, P. Guiraud, J. Jacobson, Y. Lotman, I.V. Arnold, F. Danes and others.

In order to understand the nature of the decoding stylistics, let us rely on T.A. Znamenskaya work “Stylistics of the English language”, in which she devoted the whole chapter to this problem.

T.A. Znamenskaya suggests that “decoding goes beyond the traditional analysis of a work of fiction which usually gives either an evaluative explanatory commentary on the historical, cultural, biographical or geographical background of the work and its author or suggests a kind of stylistic analysis that comprises an inventory of stylistic devices and expressive means found in the text” [Znamenskaya – 2004]. In other words, decoding stylistics concerns not only stylistics, but also other disciplines, such as history, geography, culture and others.

This theory presents a creative process in the following manner: “The writer receives diverse information from the outside world. Some of it becomes a source for his creative work. He processes this information and recreates it in his own esthetic images that become a vehicle to pass his vision to the addressee, his readers. The process of internalizing of the outside information and translating it into his imagery is called ‘encoding’” [Znamenskaya – 2004].

She supposes that neither of these approaches seems sufficient, because such kind of analysis is usually made by a literary critic and expresses only his personal comprehension of a literary work. That is why many authors show antipathy towards critical analysis of this sort as an attitude but not real evaluation.

Decoding stylistics attempts to view the esthetic value of a text, which is “based on the interaction of specific textual elements, stylistic devices and compositional structure in delivering the author's message. This method does not consider the stylistic function of any stylistically important feature separately but only as a part of the whole text. So expressive means and stylistic devices are treated in their interaction and distribution within the text as carriers of the author’s purport and creative idiom. By this the stylistic study of a literary work acquires a new, semasiological dimension in which the stylistic elements become signs of the author's vision of the world” [Znamenskaya - 2004].

Decoding stylistics assists the reader to comprehend a literary work by deciphering the data that may be concealed from immediate view in peculiar use of irony, simile, allusion, etc.

The term “decoding stylistics” came from the application of the theory of information to linguistics by such scholars as R. Jakobson, M. Riffatrre, P. Guiraud, Y. Lotman, I.V. Arnold and others.

The creative process of this theory can be briefly presented in the following mode: “the writer receives diverse information from the outside world. Some of it becomes a source for his creative work. He processes this information and recreates it in his own esthetic images that become a vehicle to pass his vision to the addressee, his readers. The process of internalizing of the outside information and translating it into his imagery is called 'encoding'” [Znamenskaya – 2004].

The process of encoding will only make any sense if besides the encoder who sends the information it includes the recipient or the addressee who in this case s the reader. “The reader is supposed to decode the information contained in the text of a literary work” [Arnold - 1990].

The author of the following lines, M.P. Brandes, has no doubt that every literary work has its own author. “The image of the author functions as the cementing power, which connects all stylistic means in the integral artistic system” [Brandes - 2004]. M.P. Brandes also admits that one cannot separate the work from its author.

|

|

A.I. Domashnev shares with M.P. Brandes the same idea: “Any literary work is a reflection of its creator in respect of the totality of ideas and their linguo-stylistic realization. It means that depicting a situation, the writer demonstrates in it his own perception of the world, his thoughts and feelings” [Domashnev – 1989].

However the encoding of the information does not mean to have it delivered intact to the recipient. On its way to the reader a literary work meets a great number of various impediments, such as temporal, historical, cultural, etc. Mostly these differences between the author and his reader are unavoidable. Authors and their readers may be separated by historical epochs, social conventions, political views, cultural traditions, etc.

Nevertheless “even if the author and the reader belong to the same society no reader can completely identify himself with the author either emotionally, intellectually or esthetically. Apart from these objective and personal factors we cannot disregard the complexity of certain works of art. Many of them are quite sophisticated in form and content” [Znamenskaya – 2004].

T.A. Znamenskaya suggests that “from the reader’s point of view the important thing is not what the author wanted to say but what he managed to convey in the text of his work. That’s why decoding stylistics deals with the notions of stylistics of the author and stylistics of the reader” [Znamenskaya - 2004].

V.A. Kukharenko in her work “the Interpretation of text” suggests that “literary work is the means of man’s cognition and mastering of the reality” [Kukharenko – 1978]. Developing this idea, V.A. Kukharenko claims that writer chooses this or that part of reality and reflects the individual process of his cognition. The writer’s choice is not chaotic. It is influenced by some factors such as social, ideological, emotional, psychological aspects.

All these factors often preclude straightforward decoding and demonstrate how complicated it is for the message to reach the reader and be correctly interpreted by him. In other words, “the message encoded and sent may differ from the message received after decoding” [Arnold – 1990].

Thus the result may be a failure on either side. “The reader may complain that he could not understand what the author wanted to say, while the author may resent being misinterpreted [Znamenskaya – 2004].

Incontrovertibly, any reader distinguishes between the stage of perceptiveness and understanding of a text at large and the stage of its linguistic analysis. “At the stage of pure text perception, unburdened by any peculiar type of analysis, we have a consecutive change of the following operations: synthesis – analysis – synthesis” [Popovskaya – 2006].

The reader first perceives a literary text as a whole, as a unity of forms, meanings and functions of language units, for, text is given to the reader in so-called a synthesized type (synthesis). After that he tries to understand its contents and sense, which is much influenced by the reader’s own cognitive basis, social experience, temperament, erudition, etc, i.e. it is influenced, according to A.J. Agaphonov, by “four sense spheres” – biosphere, cognitive, social and spiritual. Or, it is possible to say, that, the understanding comes under the influence of the reader’s own word picture - he in his own way mentally structures text (analysis). Then, again, following his own pattern, he conjoins all those parts of text into one and realizes the sense he has got in the process of this conjoinment (synthesis) [Agaphonov - 2000].

The sufficiency of text understanding by the reader depends on “the coincidence of the writer’s “sense spheres” or world picture, who synthesized language forms together with their meanings and forms into an organized whole – text, with the reader’s one, who analyzed and resynthesized these very language forms together with their meanings and functions by means of his own consciousness, using it as an instrument of analysis and synthesis. These “sense spheres” as well as world pictures will never coincide, because of differences in life experience, educational background, cultural levels, tastes, etc.” [Popovskaya – 2006].

A good illustration of the problem of mutual understanding is provided in M. Tsvetaeva's essay «Poets on Critics» in which she maintains that “reading is co-creative work on the part of the reader if he wants to understand and enjoy a work of art. Reading is not so much a hobby done at leisure as solving a kind of puzzle. What is reading but divining, interpreting, unraveling the mystery, wrapped in between the lines, beyond the words, she writes. So if the reader has no imagination no book stands a chance” [Quote by Znamenskaya – 2004].

|

|

Summarizing the idea of the above information we can formulate a conclusion that from the reader's point of view the important thing is not what the author wanted to say but what he managed to convey in the text of his work. That is why decoding stylistics deals with the notions of stylistics of the author and stylistics of the reader.

Lecture 12.

Cognitive linguistics and hermeneutics.

Cognitive linguistics studies the lg as an integral part, tool and product of human cognitive activity. Lg is viewed as a “spatial model of the real world that bears a relationship between “the real”, “The linguistic” and “The mental”.

Thus, a lg is approached as a map or a mental model of the world.

Learning a lg comes to mean learning the ways to represent the real world and human behavior in it with a foreign lg. Mental models of the world consist of the concepts that enable lg users to encode reality. Frames function as stereotypes of perceiving real-world situations, living beings, objects and processes.

Scripts are successions of acts both lingual and extra linguistic in situational settings. Another term to convey the same idea is scenario.

Schemata (schema) is an active organization of prior knowledge and cognitive processes that make a person ready to learn and to know. It consists of “slots and fillers” in the individual mind and the connections between them.

This enables cognitive processes to develop in a certain direction, in other words, schemata channel the way people perceive the world and learn to live in it.

On a less global scale, one’s individual set of beliefs channels the perception of novel situations and the behavior in them. Schemata are essential in lg comprehension and lg production for communicative purposes.

Hermeneutics is a philosophical technique concerned with the interpretation and understanding of texts. It may be described as the theory of the interpretation and understanding of a text on the basis of the text itself. The term hermeneutics, in its most common usage, denotes the science and craft of denotation, that is, the investigation of the nature of meaning, and the application of those conclusions to practical pursuits. Because of the broad nature and diverse methods of the field, its formal scholarly investigation or study is usually confined to a particular subdivision; it is rare to find a scholar or student of hermeneutics in general. An interpretive agent is sometimes referred to as a hermeneut. The concept of "text" has recently been extended beyond written documents to include, for example, speech, performances, works of art, and even events. Thus, one might speak of and interpret a "social text". Now hermeneutics is about symbolic communication, human life and existence as such. It is in this form, as an interrogation into the deepest conditions for symbolic interaction and culture in general.

The word hermeneutics is a term derived from, the Greek verb 'to interpret'. This, in turn, is derived from the Greek god Hermes in his role as the interpreter of the gods and the syncretic Ptolemaic deity Hermes Trismegistus, in his role as representing hidden or secret knowledge. The interpretation of text started quite early in ancient Greece, particularly focused on poetry, particularly that of Homer. By the time of Plato, familiarity with the Greek poets was regarded as one of the foundations of education.

A common use of the word hermeneutics refers a process of Biblical interpretation. Throughout Jewish and Christian history scholars and students of the Bible have sought to mine the wealth of its meanings by developing a variety of different systems of hermeneutics.

Hermeneutics in the Western world, as a general science of text interpretation, can be traced back to two separate sources. One source was the ancient Greek rhetoricians' study of literature, which came to fruition in Alexandria. The other source has been the Midrashic and Patristic traditions of Biblical exegesis, which were contemporary with Hellenistic culture. Scholars in antiquity expected a text to be coherent, consistent in grammar, style and outlook, and they amended obscure or "decadent" readings to comply with their codified rules. By extending the perception of inherent logic of texts, Greeks were able to attribute works with uncertain origin. One new front was opened by the sociology of science in the seventies and eighties. This re-interpretation of science often included social scientists trained in phenomenologically oriented "social construction! st" theories or the "strong program" traditions which saw that not only are scientific products historically, but socially "constituted." I shall not rehearse the full history of this set of arguments, some of which have been rather highly contested by more traditional modernist philosophers of science, but merely point out that the current generation of science interpreters seems no longer to deny that the products of science are socially constructed, rather they argue over whether these products are only social constructions implying at least that they are both/and rather than either/or.

In sociology, hermeneutics means the interpretation and understanding of social events by analysing their meanings to the human participants and their culture. It enjoyed prominence during the sixties and seventies, and differs from other interpretative schools of sociology in that it emphasizes the importance of the content as well as the form of any given social behaviour. The central principle of hermeneutics is that it is only possible to grasp the meaning of an action or statement by relating it to the whole discourse or world-view from which it originates: for instance, putting a piece of paper in a box might be considered a meaningless action unless put in the context of democratic elections, and the action of putting a ballot paper in a box. One can frequently find reference to the 'hermeneutic circle': that is, relating the whole to the part and the part to the whole. Hermeneutics in sociology was most heavily influenced by German philosopher Hans-Georg Gadamer. Hermeneutics, the 'study of interpretation, especially the

process of coming to understand text' provides an ideal framework for analyzing and understanding the activities and significance of online places inhabited by communities of writers and readers of the shared texts that form the basis of their interaction. The mechanisms of interpretation are the means through which online places are able to create robust cultural environments.

Hermeneutics as applied to sociology can be traced to the work of Max Weber who coined the term "action" to denote behavior to which the individual attaches subjective meaning. The subdiscipline in sociology, the sociology of knowledge, seeks to understand how one's position in the social structure relates to how one sees the world, so hermeneutics must be seen in the context of such variables as social class, group and subgroup memberships. Karl Marx, by postulating that the economic organization of society, its "substructure," determines its "superstructure," that contains the dominant ideas of that society, also contributed to our understanding of hermeneutics within sociology. So, in a capitalist society we have "capitalist art," "capitalist education," "capitalist philosophy," etc. As he put it: "The ruling class has the ruling ideas." One's social class position, according to Marx, largely determines his or her view of the world; his or her values and ideologies. Also, the subdiscipline of symbolic interaction utilizes hermeneutics by emphasizing how one perceives the world through his or her construction of reality, most notably promulgated by W.I Thomas' "definition of the situation," which states that if people define situations as real, they are real in their consequences. That is, we relate to each other and to the world largely based on our perceptions, rather than merely the objective features of a given situation. The interpretative nature of our social relations is a crucial area of study and may be seen to define hermeneutics within the discipline of sociology.

The hermeneutic technique is an interpretive approach concentrates on the historical meaning of human experiences and its developmental and cumulative effects on the individual and social levels; Hermeneutics is the science of understanding and interpretation. It is a formal systematic method to assist researchers in understanding and correctly interpreting human experience. Hermeneutics attempts to analyze and understand the overall perception of the individual human experience from different angles. The hermeneutic approach focuses on the linguistic and the non-linguistic actions in order to interpret the meaning of the human event. The purpose of hermeneutics inquiry is to provide a deeper understanding of a human experience. It is to provide a contextual awareness and perspective to the event. For example, the attitude of the dying individual can be better understood not by the description and meaning of the dying process but by the interpretations that the individual have regarding his/her impending death. An individual's interpretations about dying and death can be effected by his/her experiential, social, and spiritual history. Hermeneutic research design attempts to obtain a complete understanding of human event/phenomena by focusing on the entire event from all perspectives and expressions. It is a multi-level, multi-dimensional understanding of the event. It also seeks to identify the differentiation of the event. The design of the hermeneutic research model for the investigation of dying would focus on the interpretation of the meanings that are found in the dying process. Specific focus would be placed upon the dying person's definition of dying and death and any type of experiences that are related but different from the dying and death of an individual, such as the death of another individual, loss of a job, loss of physical capabilities, etc. Hermeneutic research usually concludes with an interpretative text of the about the human experience rather than a specific conclusion regarding the phenomena. Hermeneutic data collection comes from various sources and/or texts. To begin the hermeneutic review of a human experience, the researcher must make an educated guess as to the meaning of the experience and/or related text. Possible research sources or texts about dying and death may be dying individuals, and texts with various religious, social, and psychological perceptions of hematology.

Human being is a being in language. It is through language that the world is opened up for us. We learn to know the world by learning to master a language. Hence we cannot really understand ourselves unless we understand ourselves as situated in a linguistically mediated, historical culture. Language is our second nature. We never know a historical work as it originally appeared to its contemporaries. We have no access to its original context of production or to the intentions of its author. Tradition is always alive. It is not passive and stifling, but productive and in constant development. Trying, as the earlier hermeneuticians did, to locate the (scientific) value of the humanities in their capacity for objective reconstruction is bound to be a wasted effort. The past is handed over to us through the complex and ever-changing fabric of interpretations, which gets richer and more complex as decades and centuries pass. The meaning of the text is not something we can grasp once and for all. It is something that exists in the complex dialogical interplay between past and present. Just as we can never master the texts of the past, so do we fail—necessarily and constitutively—to obtain conclusive self-knowledge. Hermeneutics is about interpretation, which is about meaning, which is about what is understood.

SEMINAR 1.

General Notes on Style and Stylistics

1. Speak on the STYLISTICS as a branch of general linguistics. Define the objectives of stylistics and fields of investigation.

2. What is style? Dwell on different notions of "style” and the problem of defining the notion of style.

3. Speak on the problem of the norm. Dwell on the problem “norm”and “neutrality”.

4. Speak on the structure of stylistic phonetics, stylistic morphology, stylistic lexicology, stylistic syntax.

5. Semasiology, onomasiotogy.

6. Decoding stylistics.

7. The stylistic function.

8. Functional styles. Different approaches to their distinguishing.

Literature:

I.R. Galperin. Stylistics. Moscow, Higher school. 1977. рр. 9-25; Y.M. Screbnev. Stylistics of the English language. Moscow, 2000. pp. 7-36;

И.В. Арнольд. Стилистика. Современный английский язык. Москва, 2002 стр. 13-26, стр.. 81-88, стр. 88-98;

M. Ivashkin. A manual of English Stylistics. Nizhnii Novgorod, 1999. pp. 4-7;

V.A. Kucharcnko. A manual of English Stylistics. pp.5-10, pp. 108-120.

T.A. Znamenskaya. Stylistics of the English Language.

SEMINAR 2.

Varieties of Language

1. Speak on the spoken and written varieties of language.

2. Stylistic classification of the English vocabulary.

3. Literary vocabulary. Common literary vocabulary. Bring examples.

4. Special literary vocabulary. Bring examples.

5. Special colloquial vocabulary. Bring examples.

Literature:

I.R. Galperin. Stylistics. Moscow, Higher school. 1977. рр. 70-136; Y.M. Screbnev. Stylistics of the English language. Moscow, 2000. pp. 8-16; 52-76;

M. Ivashkin. A manual of English Stylistics. Nizhnii Novgorod, 1999. pp. 26-32;

T.A. Znamenskaya. Stylistics of the English Language.

SEMINAR 3.

Lexical and Lexico-syntactical Expressive Means and Stylistic Devices

1. Expressive Means and Stylistic Devices. Different approaches to their classification.

2. Interaction of different types of lexical meanings.

3. Metaphor.

4. Metonymy.

5. Irony.

6. Zeugma. Pun.

7. Interjections and Exclamatory words.

8. Epithets.

9. Oxymoron.

10. Antonomasia.

11. Simile.

12. Periphrasis.

13. Euphemism.

14. Hyperbole. Understatement.

15. Allusions. Intexts.

Literature:

I.R. Galperin. Stylistics. Moscow, Higher school. 1977. рр. 148-188; Y.M. Screbnev. Stylistics of the English language. Moscow, 2000. pp. 97-120;

И.В. Арнольд. Стилистика. Современный английский язык. Москва, 2002 стр. 123-136;

M. Ivashkin. A manual of English Stylistics. Nizhnii Novgorod, 1999. pp. 8-16;

V.A. Kucharcnko. A manual of English Stylistics. pp. 37-66.

T.A. Znamenskaya. Stylistics of the English Language.

SEMINAR 4.

Phonetic, graphical and syntactical stylistic devices

1. Alliteration.

2. Assonance.

3. Rhyme.

4. Rhythm.

5. Graphon.

6. Graphical Means.

7. Stylistic Inversion.

8. Detached construction.

9. Chiasmus.

10. Repetitions.

11. Climax. Anticlimax.

12. Asyndeton. Polysyndeton.

13. Ellipsis.

14. Represented Speech.

15. Rhetorical questions.

16. Litotes.

Literature:

I.R. Galperin. Stylistics. Moscow, Higher school. 1977. рр. 191-246; Y.M. Screbnev. Stylistics of the English language. Moscow, 2000. pp. 123-136; 139-143;

И.В. Арнольд. Стилистика. Современный английский язык. Москва, 2002 стр. 217-269, стр. 275-292.

M. Ivashkin. A manual of English Stylistics. Nizhnii Novgorod, 1999. pp. 44-62;

V.A. Kucharcnko. A manual of English Stylistics. Pp10-21, pp. 66-100.

T.A. Znamenskaya. Stylistics of the English Language.

Перечень вопросов к зачету

1. Speak on the STYLISTICS as a branch of general linguistics. Define the objectives of stylistics and fields of investigation.

2. What is style? Dwell on different notions of "style” and the problem of defining the notion of style.

3. Speak on the problem of the norm. Dwell on the problem “norm”and “neutrality”.

4. Speak on the structure of stylistic phonetics, stylistic morphology, stylistic lexicology, stylistic syntax.

5. Semasiology, onomasiotogy, and stylistics.

6. Decoding stylistics.

7. The stylistic function notion. Foregrounding.

8. Functional styles. Different approaches to their distinguishment.

9. Speak on the spoken and written varieties of language (binary division).

10. Stylistic classification of the English vocabulary (paradigmatic lexicology).

11. Literary vocabulary. Common literary vocabulary. Bring examples.

12. Special literary vocabulary. Bring examples.

13. Special colloquial vocabulary. Bring examples.

14. Expressive Means and Stylistic Devices. Different approaches to their classification.

15. Speak on the development of the Rhetoric. Expressive means in public speeches.

16. Metaphor.

17. Metonymy.

18. Irony.

19. Zeugma.

20. Pun.

21. Interjections and Exclamatory words.

22. Epithets.

23. Oxymoron.

24. Antonomasia.

25. Simile.

26. Periphrasis.

27. Euphemism.

28. Hyperbole. Understatement.

29. Allusions. Intexts.

30. Alliteration.

31. Assonance.

32. Rhyme.

33. Rhythm.

34. Graphon.

35. Graphical Means.

36. Stylistic Inversion.

37. Detached construction.

38. Chiasmus.

39. Repetitions.

40. Climax. Anticlimax.

41. Asyndeton. Polysyndeton.

42. Ellipsis.

43. Represented Speech.

44. Rhetorical questions.

45. Litotes.

7. Темы для самостоятельного изучения

1. Grammatical metaphor.

2. Paragraphing and exposition.

3. Methods of analysis.

4. Argumentation.

5. Means of effective presentation.

6. Narrative techniques.

7. Deconstruction.

8. Hellenistic Roman rhetoric system.

9. Ebonics.

10. Vulgarisms.

11. Stylistic synonyms.

12. The language of the drama.

Темы рефератов

1. Речевое и литературное общение как коммуникативный акт.

2. Теория функциональных стилей английского языка.

3. Язык юридических и официальных документов.

4. Язык деловой корреспонденции.

5. Язык научной и научно-популярной прозы.

6. Язык газеты и других средств массовой коммуникации (телеграмма, кино, видео и др.)

7. Язык художественной литературы как особый функциональный стиль.

8. Приемы интертекстуальности. Вертикальный контекст и его фоновое знание.

9. Методика лингвостилистического анализа художественного текста.

10. Типы повествования.

11. Композиция и образ автора.

12. Речевые характеристики персонажей, основанные на когнитивном освоении имплицитной речевой, культурологической, социально/психологической, антропологической информации текста.

13. Понимание скрытого «послания» автора как цель лингвистического анализа художественного текста.

14. Типы значения. Виды коннотации и контекста.

15. Неологизмы и инновации в современном англ. яз.

16. Современный компьютерный язык, его антропоцентричность.

17. Эвфемизмы и явление политической корректности.

18. Стилистическое использование сниженного регистра. Слэнг, просторечие, жаргон, вульгаризм – их сходство и различие, функциональная установка.

19. Выразительные средства и стилистические приемы, тропы и фигуры речи, различие между ними.

20. Виды тропов как явлений парадигматической оси, основанных на переносе значения.

21. Намеренно маркированная интертекстуальность и стилистика декодирования.

22. Текст поэтического дискурса и особенности его анализа.

23. Оппозитивные отношения языковых единиц.

24. Стилистические синонимы.

25. Композиционно-речевые формы.

26. Речевые жанры, реализуемые в официально-деловом стиле.

27. Эстетико-системное свойство внутренней формы повествования.

28. Пунктуация как стилистическое средство.

29. Типографические стилистические средства.

30. Фразеологизмы как средство стилистической выразительности.

TEST ON STYLISTICS 1

1. A ……. is a literary model in which semantic and structural features are blended so that it represents a generalized pattern.

a) figure of speech b) trope c) register d) expressive mean

2. The types of texts that are distinguished by the pragmatic aspect of communication are called…….

a) discourses b) expositions c) functional styles d) fictional styles

3. ………..style is a combination of lg units, expressive means and stylistic devices peculiar to a given writer.

a) exquisite b) individual c) neutral d) spoken

4. The ……..presupposes the oneness of the multifarious.

a) definition b) variant c) norm d) idiolect

5. …………….. of a word is not the thing or idea the word stands for, but the attitudes, feelings and emotions (associations) aroused by the word.

a) communication b) denotation c) opposition d) connotation

6. What type of connotations reveal the emotional layer of cognition and perception?

a) emotive b) evaluative c) expressive d) stylistic

7. What type of connotations aim at creating the image of the object in question?

a) emotive b) evaluative c) expressive d) stylistic

8. The ability of a verbal element to obtain extra significance in a definite context is called……

a) functioning b) foregrounding c) automatism d) conceptuality

9. The first linguistic theory called………..appeared in the 5th century BC.

a) stylistics b) sophistication c) sophistry d) didactics

10. …………..stylistics makes an attempt to regard the aesthetic value of a text based on the interaction of specific textual elements, stylistic devices and compositional structure in delivering the author’s message.

a) practical b) encoding c) decoding d) comparative

11. Stylistic study of the ………begins with the study of the length and the structure of a sentence.

a) polysemy b) expressiveness c) complication d) syntax

12. ……….sentences open with subordinated clauses, absolute and participle constructions, the main clause being withheld until the end.

a) periodic b) loose c) balanced d) incomplete

13. What SD is defined as ‘transference of meaning on the basis of contiguity’?

a) metaphor b) zeugma c) onomatopoeia d) metonymy

14. ……………….devices are based on both the interaction of lexical meanings of words and the syntactical arrangement of the elements of the utterance.

a) syntactico-lexical b) lexico-syntactical c) lexico-graphical d) lexico-variable

15. What SD represents a structure consisting of two steps, the lexical meanings of which are opposite to each other?

a) oxymoron b) litotes d) irony d) antithesis

16. ………….. is a word or phrase used to replace an unpleasant word or expression by a conventionally more acceptable one.

a) periphrasis b) understatement c) euphemism d) substitution

17. Those metaphors which are commonly used in speech and therefore are sometimes even fixed in dictionaries as expressive means of language are …….metaphors.

a) genuine b) generalized c) trite d) outmoded

18. ………….is the intentional violation of the graphical shape of a word used to reflect its authentic pronunciation.

a) occasional word b) graphon c) alliteration d) neologism

19........... - the use of a word in the same grammatical but different semantic relations to two adjacent words in the context.

a) metaphor b) allusion c) oxymoron d) zeugma

20. ………. – are words we use when we express our feelings strongly and which may be said to exist in lg as conversational symbols of human emotions.

a) exclamations b) breaks c) ellipses d) interjections

21. When the initial parts of a paragraph are repeated at the end of it we have…….

a) epiphora b) anaphora c) framing d) reduplication

22. ………..is a combination of speech-sounds which aims at imitating sounds produced in nature, by people, by machines, by animals.

a) alliteration b) onomatopoeia c) graphon d) resonance

TEST ON STYLISTICS 2

Choose the right variant:

1) “One after another those people lay down on the ground to laugh – and two of them died.”

a) Metaphor b) personification c) simile d) hyperbole

2) Would you mind getting the hell out of my way?

a) Hyperbole b) meiosis c) metaphor d) oxymoron

3) “A chiseled, ruddy face completed the not-unhandsome picture”.

a) Understatement b) oxymoron c) litotes d) hyperbole

4) “We smiled at each other, but we didn’t speak because there were ears all around us”.

a) Irony b) litotes c) metonymy d) allusions

5) I have just read two hundred pages of blood-curdling narrative.

a) Metonymy b) irony c) litotes d) periphrasis

6) He held out a hand that could have been mistaken for a bunch of bananas in a poor light.

a) Hyperbolic simile b) litotes c) ironic simile d) quasi-identity

7) His eyes were no warmer than an iceberg.

a) Litotes b) metaphor c) quasi-identity d) metonymy

8) Brandon liked me as much as Hiroshima liked the atomic bomb.

a) Simile and irony b) metonymy and irony c) litotes d) understatement and irony

9) The machine sitting at the desk was no longer a man: it was a busy New York broker.

a) Simile b) metaphor c) quasi-identity d) metonymy

10) The little boy was crying. It was the child’s usual time for going to bed, but no one paid attention to the kid.

a) Epithets b) synonymous replacements c) specifying synonyms d) climax

11) Joe was a mild, good-natured, sweet-tempered, easy-going, foolish dear fellow.

a) Epithets b) synonymous replacements c) specifying synonyms d) asyndeton

12) “…a very sweet story, singularly sweet; in fact, madam, the critics are saying it is the sweetest thing that Mr.Slush has done.’

a) irony b) climax c) metaphor d)antithesis

13) One swallow does not make a summer.

a) anti-climax b) pun d) zeugma d) metaphor

14) She dropped a tear and her pocket handkerchief.

a) anti-climax b) pun d) zeugma d) metaphor

15) O brawling love! O loving hate! O any thing! Of nothing first create.

a) oxymoron b) quasi-identity c) interjections d) epithets

16) I also assure her that I’m an Angry Young Man. A black humorist. A white Negro. Anything.

a) antithesis b) litotes c) oxymoron d) simile

17) His fees were high; his lessons were light.

a) antithesis b) litotes c) oxymoron d) simile

18) You have a kind nucleus at the interior of your exterior after all.

a) antithesis b) litotes c) oxymoron d) simile

19) I rode over to see her once every week for a while; and then I figured it out that if I doubled the number of trips I would see her twice as often.

a) oxymoron b) tautology c) simile d) understatement

20) The Major again pressed to his blue eyes the tips of the fingers that were disposed on the ledge of the wheeled chair with careful carelessness”.

a) oxymoron b) tautology c) simile d) understatement

21) The monster, in terror, had left the premises for ever!

a) nominal one-member sentence b) ellipse c) detached construction d) homogeneous element

22)They left no nook or corner unexplored.

a) onomatopoeia b) allusion c) alliteration d) litotes e) understatement

23) Drives, dinners, theatres, balls, suppers, with the gilding of superfluous wealth over all.

a) parallelism b) ellipse c) anticlimax d) enumeration

24) Off came his shirt. Off came his boots.

a) enumeration b) ellipse c) set phrase d) inversion

25) more the tepees; no more the wild stretch of prairie, no more the bed of buffalo hide…

a) parallelism b) anaphora c) climax d) enumeration

26) She was no bigger than a moth.

a)metaphor b) epithet c) personification d) understatement

27) I don’t feel a bit like a humble and pathetic ugly duckling. I do feel like a swan among gees – I can’t help it.

a) oxymoron b) simile c) epithet d) metaphor

28) Behind him the ululation swept across the island once more and a single voice shouted three times.

a) onomatopoeia b) metonymy c) epithet d) metaphor

TEST ON STYLISTICS 3

Choose the right variant:

1. Paradigmatic lexicology deals with the principles of stylistic description of lexical units in …………….. from the context in which they function.

a) description b) abstraction c) annihilation d) exploitation

2. Indispensable words, those in use everywhere, are stylistically …………

a) neutral b) coloured c) normal d) ambivalent

3. Words used only in special spheres are stylistically……………

a) neutral b) polysemantic c) coloured d) archaic

4. Obsolete, i.e. practically dead, words are also called ………….

a) barbarisms b) nonce-words c) archaisms d) bookish

5. The stylistic classification of the voc-ary takes into account the social ……….. of the word.

a) image b) identification c) phenomenon d) prestige

6. The term ‘euphemism’ implies the social practice of replacing the……….. words by words that seem less straightforward, milder, more harmless.

a) colloquial b) tabooed c) jargon d) professionalisms

7. The maximum degree of aesthetic value is demonstrated by………words.

a) official b) bookish c) neologisms d) poetic

8. The minimal degree of stylistic degradation is represented by ………..words.

a) vulgar b) slang c) professional d)colloquial

9. The words which look like “strangers” and have foreign sound are called………

a) archaisms b) denizens c) barbarisms d) nonce-words

10. ……………….are words with a tinge of informality or familiarity about them.

a) colloquialisms b) barbarisms c) vulgarisms d) archaisms

11. …………..arise due to our propensity for replacing habitual old denominations by original expressive ones, due to the striving for the novelty of expression.

a) bookish words b) neologisms c) popular terms d) slang

12. The words being created by analogy with “legitimate” words which, having served their one-time purpose, disappear completely or stay on as curiosities are called………

a) vulgarisms b) nonce-words c) neologisms d) barbarisms

13. …………….are created by and current among the people of a profession, yet their meanings pertain to everyday life, not to the professional sphere.

a) colloquialisms b) professionalisms c) jargonisms d) vulgarisms

14. Identify the class the word (phrase) is referred to:

a) oeuvre b) to goggle into the box c) to quoth d) sagacity e) alas f) alter ago

g) gee h) crutch i) womanity g) Gordian knot k) dude l) predicament

m) naught n) yellow o) balconyful p) to be nuts about

15. Write out slangy and colloquial words from the following passage:

'Well, sport! Give us a cuppa and I'll be off. I'll have to get to Kelpowie before they melt! Just got time for one cuppa.'

Treloar drank two cups. He gulped and slurped, and talked about the last race meeting. In the end he climbed back into the truck.

'Well! Must be off sport! Be seeing you in a fortnight. You got your juice didn't you? And your grub? Hey, and get us more than three hundred pair next time, will yuh?'

|

|

|

Наброски и зарисовки растений, плодов, цветов: Освоить конструктивное построение структуры дерева через зарисовки отдельных деревьев, группы деревьев...

Механическое удерживание земляных масс: Механическое удерживание земляных масс на склоне обеспечивают контрфорсными сооружениями различных конструкций...

Опора деревянной одностоечной и способы укрепление угловых опор: Опоры ВЛ - конструкции, предназначенные для поддерживания проводов на необходимой высоте над землей, водой...

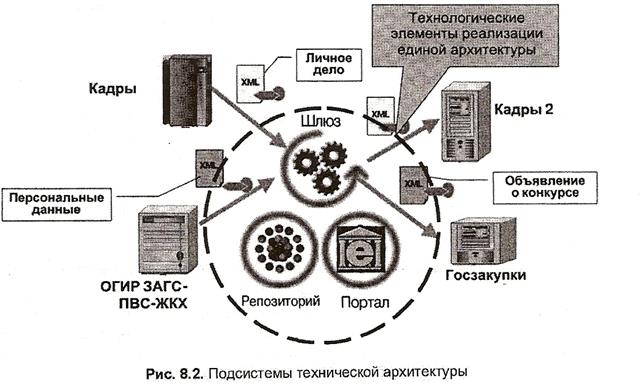

Архитектура электронного правительства: Единая архитектура – это методологический подход при создании системы управления государства, который строится...

© cyberpedia.su 2017-2024 - Не является автором материалов. Исключительное право сохранено за автором текста.

Если вы не хотите, чтобы данный материал был у нас на сайте, перейдите по ссылке: Нарушение авторских прав. Мы поможем в написании вашей работы!