Price Controlcontrol, although driven to the background in the years of deregulation, has been of increased importance in the recent trend of privatization in Europe. From a public interest perspective, price control should allow regulators to set prices at a level which induces allocative and productive efficiency. This part provides a brief, non-technical introduction to some of the tools governments have at their disposal to assure that firms meet consumer demand at efficient cost levels. For a more in-depth look at the different forms of price regulation and its analysis, reference is made to Chapter 5200, Price Regulation, which also deals with natural monopoly.

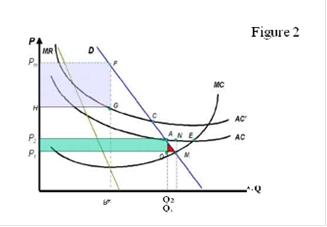

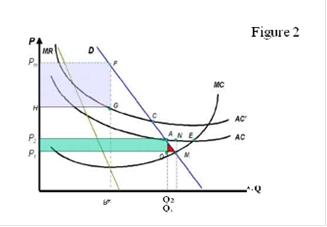

regulation, Qm in Figure 2 represents the profit-maximizing output of the monopolist and the demand, in turn, determines the market price Pm. The monopoly earns a positive economic profit represented by the area of the rectangle PmFGH. Welfare maximization to society as a whole is achieved at the quantity-price of Pi, Qi. In other words, regulating authorities should set a price P1 (marginal cost pricing) in order to maximize economic welfare. However, at price P1 consumers will buy a quantity of Q1, whereas AC is NQ1, which is greater than the price P3. This will result in a total negative economic profit, shown by the area of the rectangle P1P2AM. In the long run, the monopoly firm will not stay in business. If the commodity or service provided is desirable, the only way to keep the monopoly firm in business is to provide a public subsidy to the amount of P1 P2 AM.political problems associated with subsidization, its implementation and financing and the difficulties of calculating demand and MC have led to the application in the public utility field of average cost pricing. In Figure 2 such a price is P2, determined by the intersection of the demand and long-run AC curve. The output under average-cost pricing, Q2, is greater than the unregulated monopoly output of Qm. Also, part of the welfare costs arising from restricted output by an unregulated monopoly is eliminated. Expansion of output, from Qm to Q2 provides benefits to consumers that are greater than the additional costs.the other hand, average cost pricing can hardly be deemed entirely satisfactory either. Under average cost pricing, when Q2 is produced, welfare losses are caused because at this point average costs (the AC curve) exceed marginal costs (MC). Graphically, the AMO triangle in Figure 2 represents this consequential welfare loss. When applying a rate-of-return policy, regulating agencies focus on the rate of return on invested capital (accounting profit) earned by a monopoly (fair rate of return) (Moorehouse, 1995). Allowing regulated firms to acquire a total sum that consist of annual expenditure plus a reasonable profit on capital investment, the so-called ‘fair’ rate of return, was constructed by American courts and the regulating bodies in order to meet constitutional demands of utilities to set prices on a ‘just and reasonable’ level.can be formulated as E + (r - RB) where E represents the firms annual expenditure, r is the multiplier, representing the fair rate of return, and RB the rate (attributed value of the capital investment).the realized rate of return is higher than what is considered to be a normal return, then the price must be above average cost. In a trial-and-error fashion regulators try to locate the price where profit is normal, for example, where price equals average cost.the regulated monopolist a fair rate of return creates various economic problems that have to be taken into account. Auditing costs involved in determining the firms capital base are considerable. Especially the determination of r, which should reflect a level of return that is satisfactory to attract investment, is problematic. Looking at other ‘comparable’ industries or applying the capital asset pricing model, where one looks at the returns obtained by investors from a portfolio of investments, as modified by the difference between the returns from shares in utilities and those from more general market shares, it is clear that these are imperfect methods for determining a rate of return that potential investors will demand from the regulated industry., the perverse effects on incentives that occur when applying the standard rate of return policy are perhaps even more troublesome (Train, 1991). The regulated firm has an incentive to inflate its capital cost figures, since higher costs imply higher absolute returns (Baron and Taggart, 1977, on profit - maximizing behavior under rate of return regulation, see Hughes, 1990). If the regulator sets the fair rate of return above the cost of capital, the regulated firm is likely to utilize more capital than if it were unregulated. Thus, it might use inefficient high capital/labor ratios for its output. Also, average cost pricing diminishes the monopolist’s incentive to minimize costs. Figure 2 illustrates some of the consequences of this behavior. Inflation of costs shift the actual AC curve to AC'. At a price of P2 losses occur, therefore, regulators grant a price increase to cover the higher costs (point C).

Price Discrimination

Charging consumers different prices relative to what they are willing to pay, even though the costs of producing and supplying the goods or services are the same, has been demonstrated to enable allocative efficiency. With this technique, often referred to as Ramsey pricing, information on the price - elasticity of the different goods should allow for efficient price setting (the higher the price-elasticity, the closer the price needs to be set to marginal cost) (Ramsey, 1927). The objection often heard is that such a pricing scheme involves a wealth transfer from the consumer (consumer surplus) to the producer. Also, severe price discrimination, often termed predatory discrimination, is an effective method by which competition may be crushed out (see however for a detailed and comprehensive account McGee’s case study of the Oil of Indiana case, 1958).classical analysis of price discrimination was set out by Pigou (1920). A distinction between three degrees of discrimination was made. The first degree involves a different price set for every unit purchased by every consumer, in such a way that virtually all the possible consumer surplus is obtained by the producer. Although this pricing mechanism can be efficient, as marginal decisions are made as marginal cost, it is often opposed on income distributional grounds: the transfer from consumer to producer. Second-degree price discrimination consists of pricing groups according to their willingness to pay, where all those with a demand price above a certain level are charged one price, while those with a lower demand price are charged a lower price. Third-degree price discrimination comes into effect when consumers are divided into separate groups, each group is charged a different monopoly price. This technique is of course strongly dependent on the possibility for the seller to identify groups in each specific case, which will vary according to market circumstances.

Peak-Load Pricing

When demand follows a periodic cycle, during which demand might be high at certain times and low at others, peak-load pricing might offer a way to achieve marginal cost pricing. As marginal cost generally rises with output, price variations will allow it to reflect the higher costs. This allows for the moderation of the demand cycle while establishing a more effective use of capacity (Crew, Fernando and Kleindorfer, 1995). Higher pricing during periods of peak demand might discourage use and save costly capacity, whilst lower prices when demand is low might encourage use of capacity that otherwise would have been left idle.Regulationof the problems arising from the pricing models, such as the Averech - Johnson model find their origin in the absence of incentives to operate at minimum cost levels. The motivation behind incentive regulation is to provide the firm with the motivation to behave more consistently with regard to the social optimum.

Price-Cap Regulation or RPI-X

Requiring the firm to increase its prices for each year within a given period by no more than the retail price index (RPI) minus a variable factor (X) which is the agency’s assessment of the firm’s cost-efficiency potential, price-cap regulation was found to be superior to the fair rate of return method both in terms of efficiency and administrative costs (Littlechild and Beesley, 1992). The system, as described above, would require less information from the firms to the regulating bodies, which would not only make this model less costly but also diminish the capture problems associated with rate of return regulation.