The harvesting of timber can have far - reaching impact on wildlife.

Sensible policies and practices can benefit both the industry and the indigenous wildlife.

The Ontario Federation of Anglers and Hunters addressed the 1987 C.P.P.A. convention speaking on behalf of the interests of both sportsmen and wildlife in the hopes of fostering increased dialogue between foresters and wildlife conservationists. The O.F.A.H. believes that communication and discussion are much more effective means of dealing with resource-related issues than is antagonism. Secondly, the O.F.A.H. feels that foresters have a far greater influence over vast areas of habitat than do the attendant wildlife agencies and that, consequently, it may be more effective to deal with these interested parties than to attempt to manage wildlife directly.

Forestry practitioners have no direct responsibility for wildlife. But through their activities they are probably the nation's number one wildlife habitat managers. The O.F.A.H. is offering support for their efforts at wise resource management, and offering suggestions as to how they might ensure that their activities are carried out to conserve and even enhance wildlife populations. This working paper is derived from wildlife literature, personal experience, and our own policies. It is a step in the development of our own policy on forestry matters.

Logging activities change the landscape in subtle and perhaps drastic ways. In part, these changes resemble those resulting from natural disturbances such as fires and windstorms. Wildlife is naturally affected by such large scale habitat changes. The result can be detrimental, neutral, or even beneficial to certain species. Woodland caribou range may be reduced, for example. Chipmunks may be as abundant as ever. And white-tailed deer may become more plentiful when mature boreal or mixed wood forests are cut.

Forestry practice and planning will influence how well wildlife copes with these changes, and determines the mixture of wildlife species and habitats that remain in the boreal forest for our children. Forestry is evolving, as is our knowledge of the requirements of wildlife species. As hunters, anglers, and conservationists, we would like to see forestry evolve to incorporate the needs of wildlife and the needs of the public to enjoy this wildlife.

This paper cannot examine all aspects of forestry/wildlife integration, so it will focus on seven major themes where the O.F.A.H. feels wildlife interests would be addressed in forestry. These are not our only concerns, but are major areas of interest. I will address the subjects of moose habitat and clearcut size, habitat diversity through plantation management, snag habitat management, fish habitat protection, pesticide and herbicide use, access roads, and public involvement specifically. I hope to bring home the point that forestry affects wildlife, and that incorporation of wildlife interests into forestry need not be a difficult task.

Moose management

The Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources has stated that "Timber cutting is one of the major producers of moose habitat in the province of Ontario and without this disturbance, moose populations would be lower." You might get several applications to join the C.P.P.A. if more sportsmen were aware of this fact. Forestry now creates the young successional stands which at one time followed widespread forest fires. Moose browse on twigs and buds of willow, birch and aspen that occur in these young stands, and now benefit from logging operations. Forestry also benefits the public by creating access roads for hunting and viewing opportunities. However, moose also require mature stands of conifers as wintering areas and they depend on productive aquatic feeding areas in lakes and streams in spring and early summer. They depend on a diverse, healthy landscape where all of these features are in close proximity.

Large block clearcuts are not good for moose and the majority of other forest wildlife. Open, overgrown expanses do not promote movement of animals like moose and deer to the feeding or yarding areas. These sites are much more prone to erosion than smaller clearcuts, and may contribute to siltation of streams and destruction of spawning beds. From a game conservation perspective, animals like moose are very exposed to both elements and to hunting. When the ratio of uncut to cut areas shifts towards the latter, most wildlife populations do not benefit. There are some that do benefit, of course. Least chipmunks, meadow voles, and sparrows and other species flourish in clearcuts. The Federation realizes that clear-cutting is the cutting practice for many northern forests, so we developed suggestions to help keep the practice as undamaging to wildlife as possible.

We propose that wherever feasible, small clearcuts or strip cuts should be favored. If large tracts are to be cut, design them in rectangular blocks that maximize edge and minimize distance to cover for animals foraging in the cuts. There is a rule of thumb stating that in general, moose will not travel more than 200m into cutovers. If cuts are not larger than 400m wide, therefore, moose will likely use the entire area, while benefitting from adjacent cover. We agree with the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources guideline that clearcuts greater than 100ha should contain shelter patches within the cutover area. These could be of mixed wood, around three to five hectares. We consider clearcuts larger than 120 ha to be unacceptable.

Woodland caribou

Woodland caribou have disappeared from large areas of the boreal forest. Logging has contributed to this loss, along with fires, hunting and predation mortality, and disease. Although we don't know exactly what caribou need to survive, we do know that in winter, they depend on tree and ground lichens that are typical of old growth forests. In areas where woodland caribou occur, care should be taken to ensure adequate habitat is available for this wide-ranging species. To a certain extent, forest lands reserved from cutting, such as rocky areas with little soil, can contribute to caribou habitat conservation. Otherwise, some old growth or mature stands should be protected. The C.P.P.A. and other forestry groups have produced publications on wildlife, demonstrating an interest in the subject. We believe that if woodland caribou can be accommodated in areas of managed forests, true forestry/wildlife integration would be achieved.

Snag protection

Disturbance caused by forestry creates new habitat, and in this way mimics some fires. However, one aspect is certainly different. Following a fire, large numbers of dead trees (snags, chicots) are left standing in the burned area. As the forest regrows, the snags provide prime nesting sites for woodpeckers. These and other cavity-nest species are voracious insect eaters. The diet of these and other insectivorous birds can be more than 80 per cent destructive forest insects. One study from the State of Washington showed that predation of birds on western spruce budworm was the equivalent of $1,820 per square mile per year of insecticides over a 100-year rotation. There are similar figures available for Canadian forests. The point is that bird predation helps foresters and can be enhanced by enlightened forestry practice.

It is common practice to cut down snags during clearcutting operations, often for safety reasons. And if reseeding or replanting follows a burn, site preparation eliminates most snags or potential snags from a site. The benefits of snags to many wildlife species is well-documented, and I direct interested persons to the U.S.D.A. Forest Service Handbook on Wildlife Habitats in Managed Forests for examples. With a minimal amount of effort, we believe this component of wildlife habitat can be protected. We recommend that during site preparation, patches of dead standing timber be left intact to provide cavity-nesting habitat. And secondly, we propose that should the felling of all snags during logging continue, foresters should consider replacing some of these trees, perhaps through girdling. Girdled trees remain standing as the new stand grows toward maturity.

Once cavities exist, other species such as flying squirrels and flycatchers move in as well. An entire wildlife community depends on snags, and this community is affected when snags disappear. As well, the small stands of live trees we recommend leaving in clearcuts will provide nesting habitat for other insect-eating birds like warblers, whose activities can only benefit foresters.

If salvage logging is to be undertaken, the U.S.D.A. Forest Service recommends leaving broken-topped, twisted and heavily-limbed snags for wildlife, while harvesting more valuable ones, and leaving snags in areas that are difficult to cut. A third approach would be to leave soft snags, that is, those that are too decayed to be merchantable, wherever possible.

Intensive forestry in Europe has reached a point where they have to add nest boxes to entice insectivorous birds to their plantations. In Canada we have yet to reach that point. The protection of snags should be able to provide this benefit to foresters and to wildlife populations.

Planning plantations

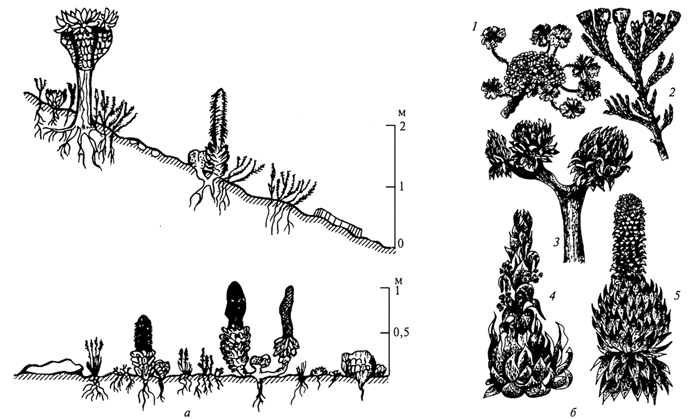

One common misconception among the general public is that plantations that replace natural regeneration are sterile environments devoid of wildlife. This is not so, and in fact the effect can be just the opposite. Dr. Jim Bendall of the Faculty of Forestry at the University of Toronto has been examining the effects of plantation habitats on wildlife, and has some interesting results. He has studied primarily jack pine and spruce forests around Gogama, Ontario. Population increases reaching epidemic levels have been observed in heather voles, spruce grouse, varying hare and even some song bird species. Why these "outbreaks" occur is not clear, but it could be due to the homogenous nature of the habitat and thus the local concentration of resources associated with that age class and forest type.

Species able to exploit concentrated resources such as certain shrub and understory plant species, and even the trees themselves, can do extremely well. Bendall's group has reported the highest densities of heather voles ever recorded, and noted the highest spruce grouse densities in North America. They point out that few studies exist on the fauna of plantations, and that in general we know very little about how forestry affects wildlife.

So it is evident that some wildlife species benefit from even-aged, structurally similar plantations. However, so do some of our most destructive forest pests. To alleviate the potential for pest outbreaks and achieve a healthy balance of habitat for all wildlife species, we recommend the planning of cutting and plantations to create a mixture of age classes over the landscape. Rather than large blocks of relatively homogenous habitat, a mosaic of stand ages would be preferred, including a small portion of old-growth habitat.

Larry Harris, in his award-winning book The Fragmented Forest, suggested: "a system of long rotation islands of intact old growth, contiguous with a shifting mosaic of old and new forest stands.” The configuration and cutting plans associated with this system are best left with foresters, but preferably old growth and other reserves should protect natural features such as waterways, moose wintering yards and the sensitive features.

The O.F.A.H. has developed a policy on access roads. Basically, we are in favor of access to public land and public resources for all people. We feel that the blocking of access roads or limiting their use to a single user group is not a wide management strategy. In many cases, public funds helped pay for road construction, and we feel the public should be allowed to use them.

We realize that there are problems associated with increased access, and do not take lightly the risks of increased fire, poaching, or vandalism of forestry equipment. We feel such problems are associated with a minority of users and with proper precautions, including increased policing, these negative effects can be minimized. Closing off roads because of the deleterious effects of a few people is like prohibiting logging in some areas because of the deleterious practices of a few companies. Access provides valuable hunting, wildlife viewing and other recreational opportunities.

Hunting pressure, we know, can be concentrated around roads and can preferentially affect local game populations. Therefore, in some cases it may be necessary to post "NO DISCHARGE OF FIREARMS" signs similar to those used around cutting sites, for the protection of game that becomes attracted to and exposed in larger clearcuts.

Access roads can provide habitat management opportunities. Specifically, we recommend spreading clover seed to help the re-vegetation of roadsides, landings or other disturbed clearings. These, we feel, will benefit populations of game species such as moose, deer and grouse.

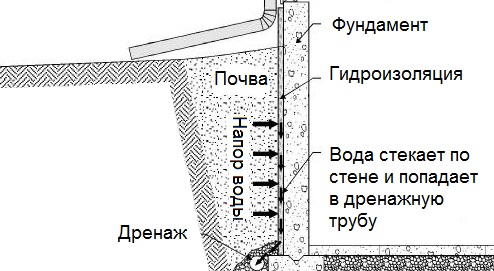

Minimizing effects on fish

The traditional shoreline reserves associated with streams and lakes have, until recently, protected important fish spawning and feeding habitat, by reducing siltation and maintaining cover that keeps some water-bodies cool. New approaches, at least in Ontario, are providing foresters the option of cutting right down to shoreline, as long as sensitive areas such as aquatic feeding sites and spawning areas are protected. We are in favor of strategies that maximize fibre production while minimizing effects on fish and wildlife, but we do believe that caution should be taken in this interface between land and water. It is a very diverse and productive habitat. If cutting of trees occurs down to lakeshores, we feel that shoreline cover should be maintained to decrease; the effects of erosion. This can be accomplished through selective logging. Although warm water lakes may not suffer from increased sedimentation and the reduction of shade from shoreline trees, only minimal disturbance should be allowed in this sensitive zone.

We are also in favor of maintaining vegetation and the reduction of

mechanical disturbance along feeder streams and small waterways in cutting areas. These may not harbour game fish populations, but they contribute to the health of fish-bearing lakes and streams and should be damaged as little as possible. Silt goes a long way.

Wise use of pesticides

The use of herbicides and pesticides warrants separate consideration. They represent a major way in which forestry differs from natural disturbance. The suppression of competing organisms by mostly chemical means alters the forest in ways for which forest organisms are ecologically unprepared. Herbicides reduce the abundance of willows, birches and other shrubs that feed game animals and which are part of the natural process of nutrient cycling and stand development. We believe that little is known of the longterm effectiveness and safely of herbicide use in forestry, and that much more research and monitoring of their impacts needs to be done before we can fully endorse this strategy. We do feel that manual approaches should be utilized to their utmost potential.

The O.F.A.H. believes in the judicious use of chemical insecticides to control pest epidemics, but it also supports the development of more ecologically sound alternatives such as biological agents and vegetation management. The biological agent B.t. is one example of a new approach that has been helpful, but is not the answer to pest problems. Research in Ontario has shown that Bt killed (as planned) mainly lepidopterous larvae — but that this killing resulted in the reduction in hatchling success of birds like the spruce grouse. The long-term effects of this agent on nontarget populations is not known, but the data points out that no pest control strategy should be carved in stone. The best alternative should be used at the best time. Spraying schedules, for example, should be timed to the biology of the insect in question, not necessarily to strategy written on paper.

As we learn more about forest wildlife, we are learning new connections

in the pest predator food chains. Larvae of pests such as the jackpine and spruce budworm are known to pupate on the ground. Research has shown that small mammals and birds eat tremendous quantities of these pupae, so many that few adult insects may emerge. And in Newfoundland, one small mammal has actually been airlifted in to help combat a forest insect pest. In 1958, the masked shrew (sorex cinereus), a small but common insectivorous mammal of northern forests, was introduced to Newfoundland to help combat the effects of larch sawfly, which happens to pupate in the soil. We don’tI know how effective the approach was but the Canadian Forestry Service feels their predation is considerable.

4. Переведите вопросы и ответьте на них:

1. How do logging activities change the landscape?

2. What are the major themes of forestry wildlife integration mentioned in the article?

3. What kinds of clearcuts should be favoured to preserve the majority of forest wildlife?

4. What is snag protection necessary for?

5. Why is planning of cutting and plantations recommended?

6. What do access roads provide?

7. What are the strategies minimizing effects on fish mentioned in the article?

8. What is the effect of herbicide usage?

5. Переведите на слух:

To manage wildlife; лесозаготовки; large scale habitat changes; размер, площадь вырубаемых лесов; wide-spread forest fires; места зимования; to be prone to erosion; гибель хищных животных; the wide–ranging species; спелое насаждение; in areas of managed forests; напоминать по результатам воздействия пожара; bird predation; вырубить сухостойный лес; girdled trees; заготовка поврежденных деревьев; to lean soft snags; интенсивное лесопользование; to replace natural regeneration of forest; воздействовать на дикую природу; even-aged, structurally-similar plantations.

6. Переведите текст (рекомендуется для письменного перевода):