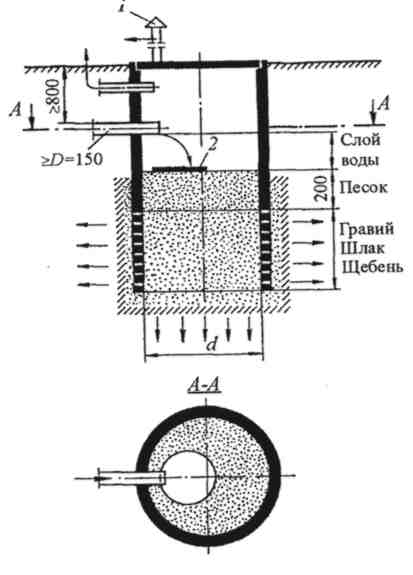

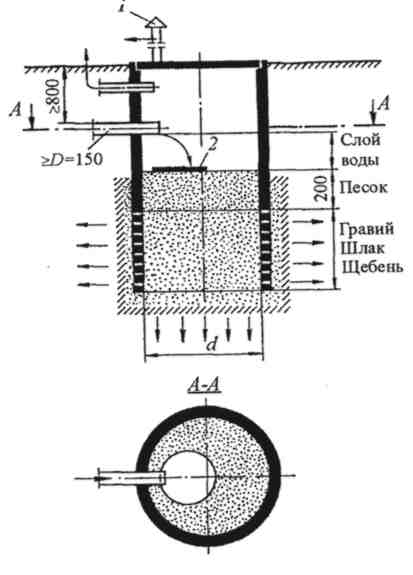

Индивидуальные очистные сооружения: К классу индивидуальных очистных сооружений относят сооружения, пропускная способность которых...

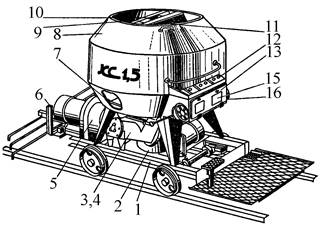

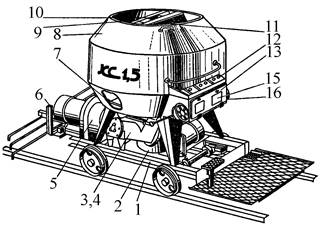

Кормораздатчик мобильный электрифицированный: схема и процесс работы устройства...

Индивидуальные очистные сооружения: К классу индивидуальных очистных сооружений относят сооружения, пропускная способность которых...

Кормораздатчик мобильный электрифицированный: схема и процесс работы устройства...

Топ:

Установка замедленного коксования: Чем выше температура и ниже давление, тем место разрыва углеродной цепи всё больше смещается к её концу и значительно возрастает...

Выпускная квалификационная работа: Основная часть ВКР, как правило, состоит из двух-трех глав, каждая из которых, в свою очередь...

Комплексной системы оценки состояния охраны труда на производственном объекте (КСОТ-П): Цели и задачи Комплексной системы оценки состояния охраны труда и определению факторов рисков по охране труда...

Интересное:

Принципы управления денежными потоками: одним из методов контроля за состоянием денежной наличности является...

Национальное богатство страны и его составляющие: для оценки элементов национального богатства используются...

Финансовый рынок и его значение в управлении денежными потоками на современном этапе: любому предприятию для расширения производства и увеличения прибыли нужны...

Дисциплины:

|

из

5.00

|

Заказать работу |

|

|

|

|

“What’s the matter (что случилось)?” asked Kemp, when the Invisible Man admitted him (спросил Кемп, когда Невидимка впустил его; to admit — допускать, соглашаться; впускать).

“Nothing (ничего),” was the answer (был ответ).

“But, confound it! The smash (но, черт возьми, шум /почему/)?”

“Fit of temper (приступ раздражительности),” said the Invisible Man. “Forgot this arm (забыл про эту руку); and it’s sore (а она болит; sore — больной; болезненный, чувствительный; воспаленный).”

“You’re rather liable to that sort of thing (вы весьма подвержены подобного рода приступам; that sort of thing — тому подобное, вещи такого рода).”

“I am (да).”

answer [`Rnsq], sore [sL], liable [`laIqbl]

“What’s the matter?” asked Kemp, when the Invisible Man admitted him.

“Nothing,” was the answer.

“But, confound it! The smash?”

“Fit of temper,” said the Invisible Man. “Forgot this arm; and it’s sore.”

“You’re rather liable to that sort of thing.”

“I am.”

Kemp walked across the room and picked up the fragments of broken glass (Кемп прошел через комнату с подобрал осколки разбитого стакана).

“All the facts are out about you (все про вас теперь известно; to be out — публиковаться; становиться общеизвестным),” said Kemp, standing up with the glass in his hand (сказал Кемп, вставая со стаканом в руках); “all that happened in Iping, and down the hill (все, что произошло в Айпинге и у холма). The world has become aware of its invisible citizen (мир узнал о своем невидимом гражданине). But no one knows you are here (но никто не знает, что вы здесь).”

The Invisible Man swore (Невидимка выругался; to swear — клясться; клясть; ругаться).

“The secret’s out (тайна раскрыта). I gather it was a secret (полагаю, это была тайна). I don’t know what your plans are (я не знаю, каковы ваши планы), but of course I’m anxious to help you (но, конечно, с готовностью вам помогу; anxious — озабоченный, беспокоящийся; сильно желающий).”

The Invisible Man sat down on the bed (Невидимка сел на кровати).

citizen [`sItIz(q)n], secret [`sJkrIt], anxious [`xNkSqs]

Kemp walked across the room and picked up the fragments of broken glass.

“All the facts are out about you,” said Kemp, standing up with the glass in his hand; “all that happened in Iping, and down the hill. The world has become aware of its invisible citizen. But no one knows you are here.”

|

|

The Invisible Man swore.

“The secret’s out. I gather it was a secret. I don’t know what your plans are, but of course I’m anxious to help you.”

The Invisible Man sat down on the bed.

“There’s breakfast upstairs (наверху сервирован завтрак),” said Kemp, speaking as easily as possible (сказал Кемп, /говоря/ как можно непринужденнее: «настолько непринужденно, насколько возможно»), and he was delighted to find his strange guest rose willingly (и с радостью увидел, что его странный гость охотно встал). Kemp led the way up the narrow staircase to the belvedere (Кемп повел его по узкой лестнице наверх, в бельведер).

“Before we can do anything else (прежде чем мы что-нибудь предпримем),” said Kemp, “I must understand a little more about this invisibility of yours (я должен узнать немного больше об этой вашей невидимости).”

He had sat down, after one nervous glance out of the window (Кемп сел, бросив нервный взгляд в окно), with the air of a man who has talking to do (с видом человека, которому предстоит /долгая/ беседа). His doubts of the sanity of the entire business flashed and vanished again (его сомнения насчет разумности всего происходящего снова быстро промелькнули и исчезли) as he looked across to where Griffin sat at the breakfast-table (когда он посмотрел через сервированный для завтрака стол туда, где сидел Гриффин) — a headless, handless dressing-gown (безголовый, безрукий халат), wiping unseen lips on a miraculously held serviette (вытиравший невидимые губы чудесным образом удерживаемой салфеткой).

glance [glRns], doubt [daut], miraculously [mI`rxkjulqslI], serviette ["sq:vI`et]

“There’s breakfast upstairs,” said Kemp, speaking as easily as possible, and he was delighted to find his strange guest rose willingly. Kemp led the way up the narrow staircase to the belvedere.

“Before we can do anything else,” said Kemp, “I must understand a little more about this invisibility of yours.”

He had sat down, after one nervous glance out of the window, with the air of a man who has talking to do. His doubts of the sanity of the entire business flashed and vanished again as he looked across to where Griffin sat at the breakfast-table — a headless, handless dressing-gown, wiping unseen lips on a miraculously held serviette.

“It’s simple enough — and credible enough (это довольно просто и вполне реально),” said Griffin, putting the serviette aside (сказал Гриффин, отложив салфетку в сторону) and leaning the invisible head on an invisible hand (и подперев невидимую голову невидимой рукой).

“No doubt, to you, but — (несомненно, для вас, но…)” Kemp laughed (Кемп засмеялся).

|

|

“Well, yes; to me it seemed wonderful at first, no doubt (ну да, мне это, конечно, сначала казалось поразительным). But now, great God (но теперь, Боже милостивый)!.. But we will do great things yet (но мы еще свершим великие дела)! I came on the stuff first at Chesilstowe (впервые я занялся этим вопросом в Чезилстоу; to come on — возникать /о вопросе/; наталкиваться).”

“Chesilstowe?”

credible [`kredqbl], laughed [lRft], wonderful [`wAndqf(q)l]

“It’s simple enough — and credible enough,” said Griffin, putting the serviette aside and leaning the invisible head on an invisible hand.

“No doubt, to you, but — ” Kemp laughed.

“Well, yes; to me it seemed wonderful at first, no doubt. But now, great God!.. But we will do great things yet! I came on the stuff first at Chesilstowe.”

“Chesilstowe?”

“I went there after I left London (a переехал туда после того, как покинул Лондон). You know I dropped medicine and took up physics (знаете, я бросил медицину и занялся физикой; to take up — поднимать; подхватывать; браться /за что-либо/; заниматься /чем-либо/)? No? well, I did (не знаете? ну, в общем, это так). Light fascinated me (свет очаровал меня = я увлекся изучением света).”

“Ah (а-а)!”

“Optical density (оптическая плотность)! The whole subject is a network of riddles (весь этот вопрос — сеть загадок) — a network with solutions glimmering elusively through (сеть, сквозь которую неуловимо мерцают решения; elusive — ускользающий). And being but two-and-twenty and full of enthusiasm, I said (будучи всего лишь двадцати двух лет, полный энтузиазма, я сказал), ‘I will devote my life to this (я посвящу свою жизнь этому /вопросу/). This is worth while (он того стоит; worth one's while — стоит затраченного времени или труда).’ You know what fools we are at two-and-twenty (знаете, каким дураком бываешь в двадцать два)?”

“Fools then or fools now (дураком тогда или дураком теперь = может, это теперь мы дураки),” said Kemp.

medicine [`meds(q)n], physics [`fIzIks], enthusiasm [In`thjHzIxz(q)m]

“I went there after I left London. You know I dropped medicine and took up physics? No? well, I did. Light fascinated me.”

“Ah!”

“Optical density! The whole subject is a network of riddles — a network with solutions glimmering elusively through. And being but two-and-twenty and full of enthusiasm, I said, ‘I will devote my life to this. This is worth while.’ You know what fools we are at two-and-twenty?”

“Fools then or fools now,” said Kemp.

“As though knowing could be any satisfaction to a man (как будто знание может принести удовлетворение)!

“But I went to work — like a slave (но я принялся за работу, будто проклятый: «раб»; to work like a slave — трудиться до изнеможения; работать как каторжный). And I had hardly worked and thought about the matter six months (и я усиленно/тяжело работал и размышлял над проблемой шесть месяцев) before light came through one of the meshes suddenly — blindingly (прежде чем внезапно свет проник через одну из ячеек сети /незнания/ — слепящий свет)! I found a general principle of pigments and refraction (я нашел общий принцип пигментов и преломления /световых лучей/) — a formula, a geometrical expression involving four dimensions (формулу, геометрическое выражение /которой/ включает четыре измерения). Fools, common men, even common mathematicians (дураки, обычные люди, даже обыкновенные математики), do not know anything of what some general expression may mean (не знают ничего о том, что может означать = не представляют, какое значение может иметь какое-либо общее выражение) to the student of molecular physics (для изучающего молекулярную физику). In the books — the books that tramp has hidden (в книгах — в тех книгах, которые украл этот бродяга) — there are marvels, miracles (есть удивительные вещи, чудеса)! But this was not a method, it was an idea (но это не был метод/способ, это была идея), that might lead to a method by which it would be possible (которая может привести к методу, с помощью которого было бы возможным), without changing any other property of matter (не изменяя каких-либо свойств материи) — except, in some instances colours (кроме, в отдельных случаях, цвета) — to lower the refractive index of a substance (уменьшить коэффициент преломления вещества), solid or liquid, to that of air (твердого или жидкого, — до коэффициента преломления воздуха) — so far as all practical purposes are concerned (насколько требуется для практических целей).”

|

|

formula [`fLmjulq], molecular [mq`lekjulq], miracle [`mIrqkl]

“As though knowing could be any satisfaction to a man!

“But I went to work — like a slave. And I had hardly worked and thought about the matter six months before light came through one of the meshes suddenly — blindingly! I found a general principle of pigments and refraction — a formula, a geometrical expression involving four dimensions. Fools, common men, even common mathematicians, do not know anything of what some general expression may mean to the student of molecular physics. In the books — the books that tramp has hidden — there are marvels, miracles! But this was not a method, it was an idea, that might lead to a method by which it would be possible, without changing any other property of matter — except, in some instances colours — to lower the refractive index of a substance, solid or liquid, to that of air — so far as all practical purposes are concerned.”

“Phew (ну и ну)!” said Kemp. “That’s odd (это странно)! But still I don’t see quite (но все-таки мне не совсем ясно)... I can understand that thereby you could spoil a valuable stone (я понимаю, что таким образом вы могли бы испортить драгоценный камень), but personal invisibility is a far cry (но личная невидимость = сделать невидимым человека, до этого еще далеко; far cry — большое расстояние; большая разница: «дальний крик»).”

“Precisely (совершенно верно; precise — точный),” said Griffin. “But consider, visibility depends on the action of the visible bodies on light (но подумайте: видимость зависит от реакции видимых тел на свет; to consider — рассматривать). Either a body absorbs light (тело либо поглощает свет), or it reflects or refracts it (либо отражает, либо преломляет его), or does all these things (или все это вместе). If it neither reflects nor refracts nor absorbs light (если оно не отражает, не преломляет и не поглощает свет), it cannot of itself be visible (то оно само по себе не может быть видимым). You see an opaque red box, for instance (вы видите непрозрачный красный ящик, например), because the colour absorbs some of the light and reflects the rest (потому что его цвет поглощает часть света и отражает остальное), all the red part of the light, to you (всю красную часть света, вам /в глаза/). If it did not absorb any particular part of the light (если бы он не поглощал определенной доли света), but reflected it all (а отражал бы его весь), then it would be a shining white box (то был бы блестящим белым ящиком).

|

|

phew [fjH], opaque [qu`peIk], neither [`naIDq], absorb [qb`zLb]

“Phew!” said Kemp. “That’s odd! But still I don’t see quite... I can understand that thereby you could spoil a valuable stone, but personal invisibility is a far cry.”

“Precisely,” said Griffin. “But consider, visibility depends on the action of the visible bodies on light. Either a body absorbs light, or it reflects or refracts it, or does all these things. If it neither reflects nor refracts nor absorbs light, it cannot of itself be visible. You see an opaque red box, for instance, because the colour absorbs some of the light and reflects the rest, all the red part of the light, to you. If it did not absorb any particular part of the light, but reflected it all, then it would be a shining white box.

“Silver (/как/ серебро)! A diamond box would neither absorb much of the light (алмазный ящик не поглощал бы много света) nor reflect much from the general surface (и не отражал бы много света от своей поверхности; general surface — общая поверхность), but just here and there where the surfaces were favourable (но местами, там, где находятся подходящие поверхности: «но только здесь и там, где поверхности были бы благоприятны») the light would be reflected and refracted (свет отражался и преломлялся бы), so that you would get a brilliant appearance of flashing reflections and translucencies (так что вы увидели бы блестящую паутину сверкающих отражений и полупрозрачных плоскостей; appearance — внешний вид, наружность; translucency — полупрозрачность, просвечиваемость) — a sort of skeleton of light (своего рода световой скелет). A glass box would not be so brilliant (стеклянный ящик не был бы таким блестящим), not so clearly visible, as a diamond box (и не был бы так ясно видим, как алмазный), because there would be less refraction and reflection (потому что в нем меньше /плоскостей/ преломления и отражения). See that (понимаете)?

“From certain points of view you would see quite clearly through it (с определенных точек наблюдения вы могли бы совершенно ясно смотреть сквозь него). Some kinds of glass would be more visible than others (некоторые сорта стекла более видимы, чем другие), a box of flint glass would be brighter than a box of ordinary window glass (ящик из хрусталя был бы более блестящим, чем ящик из обычного оконного стекла; flint glass — флинтглас /сорт оптического стекла, обладающего большим показателем преломления/; хрусталь). A box of very thin common glass would be hard to see in a bad light (ящик из очень тонкого обыкновенного стекла было бы труднее различить при плохом освещении), because it would absorb hardly any light (потому что он почти не поглощал бы света) and refract and reflect very little (и очень мало света преломлял и отражал бы). And if you put a sheet of common white glass in water (а если вы положите лист обыкновенного прозрачного стекла в воду), still more if you put it in some denser liquid than water (или, еще лучше, если положите его в какую-нибудь жидкость, более плотную, чем вода), it would vanish almost altogether (он исчезнет почти полностью), because light passing from water to glass (поскольку свет, переходя из воды в стекло) is only slightly refracted or reflected (лишь слегка преломляется и отражается) or indeed affected in any way (и вообще на него не оказывается почти никакого воздействия). It is almost as invisible as a jet of coal gas or hydrogen is in air (/в данном случае/ стекло почти такое же невидимое, как струя угарного газа или водорода в воздухе). And for precisely the same reason (и именно по той же самой причине)!”

|

|

translucency [trxnz`lHs(q)nsI], skeleton [`skelIt(q)n], hydrogen [`haIdrqGqn]

“Silver! A diamond box would neither absorb much of the light nor reflect much from the general surface, but just here and there where the surfaces were favourable the light would be reflected and refracted, so that you would get a brilliant appearance of flashing reflections and translucencies — a sort of skeleton of light. A glass box would not be so brilliant, not so clearly visible, as a diamond box, because there would be less refraction and reflection. See that?

“From certain points of view you would see quite clearly through it. Some kinds of glass would be more visible than others, a box of flint glass would be brighter than a box of ordinary window glass. A box of very thin common glass would be hard to see in a bad light, because it would absorb hardly any light and refract and reflect very little. And if you put a sheet of common white glass in water, still more if you put it in some denser liquid than water, it would vanish almost altogether, because light passing from water to glass is only slightly refracted or reflected or indeed affected in any way. It is almost as invisible as a jet of coal gas or hydrogen is in air. And for precisely the same reason!”

“Yes,” said Kemp, “that is pretty plain sailing (это все очень просто; plain sailing — простое, легкое дело, пустяки; проще простого: «простая навигация»; sail — парус).”

“And here is another fact you will know to be true (а вот еще один факт, который, как вам известно, является правдой = который вы, несомненно, знаете). If a sheet of glass is smashed, Kemp (если лист стекла разбит, Кемп), and beaten into a powder (и истолчен в порошок), it becomes much more visible while it is in the air (оно станет гораздо более видимым, находясь на воздухе); it becomes at last an opaque white powder (в конце концов оно превратится в непрозрачный белый порошок). This is because the powdering multiplies the surfaces of the glass (это происходит потому, что превращение в порошок увеличивает /число/ поверхностей стекла) at which refraction and reflection occur (на которых происходит преломление и отражение). In the sheet of glass there are only two surfaces (в листе стекла только две поверхности); in the powder the light is reflected or refracted by each grain it passes through (в порошке свет отражается или преломляется каждой крупинкой, через которую проходит), and very little gets right through the powder (и очень мало /света/ проходит прямо через порошок). But if the white powdered glass is put into water (но если белый стеклянный порошок помещен в воду), it forthwith vanishes (он тотчас исчезает). The powdered glass and water have much the same refractive index (стеклянный порошок и вода имеют почти одинаковый коэффициент преломления); that is, the light undergoes very little refraction or reflection in passing from one to the other (то есть свет подвергается очень незначительному преломлению и отражению при переходе из одной /среды/ в другую).

true [trH], powder [`paudq], surface [`sq:fIs], multiply [`mAltIplaI]

“Yes,” said Kemp, “that is pretty plain sailing.”

“And here is another fact you will know to be true. If a sheet of glass is smashed, Kemp, and beaten into a powder, it becomes much more visible while it is in the air; it becomes at last an opaque white powder. This is because the powdering multiplies the surfaces of the glass at which refraction and reflection occur. In the sheet of glass there are only two surfaces; in the powder the light is reflected or refracted by each grain it passes through, and very little gets right through the powder. But if the white powdered glass is put into water, it forthwith vanishes. The powdered glass and water have much the same refractive index; that is, the light undergoes very little refraction or reflection in passing from one to the other.

“You make the glass invisible by putting it into a liquid of nearly the same refractive index (вы делаете стекло невидимым, помещая его в жидкость с примерно таким же коэффициентом преломления); a transparent thing becomes invisible (прозрачная вещь становится невидимой) if it is put in any medium of almost the same refractive index (если помещается в какую-либо среду, обладающую почти одинаковым с ней коэффициентом преломления). And if you will consider only a second (а если вы секунду подумаете), you will see also that the powder of glass might be made to vanish in air (вы также поймете, что стеклянный порошок можно сделать невидимым в воздухе: «может быть заставлен исчезнуть в воздухе»), if its refractive index could be made the same as that of air (если суметь сделать его коэффициент преломления таким же, как и у воздуха); for then there would be no refraction or reflection as the light passed from glass to air (поскольку тогда не будет ни преломления, ни отражения, когда свет переходит из стекла в воздух).”

“Yes, yes,” said Kemp. “But a man’s not powdered glass (но человек — не стеклянный порошок)!”

“No (нет),” said Griffin. “He’s more transparent (он прозрачнее)!”

“Nonsense (вздор: «бессмыслица»)!”

medium [`mJdIqm], consider [kqn`sIdq], transparent [trxn`spxrqnt]

“You make the glass invisible by putting it into a liquid of nearly the same refractive index; a transparent thing becomes invisible if it is put in any medium of almost the same refractive index. And if you will consider only a second, you will see also that the powder of glass might be made to vanish in air, if its refractive index could be made the same as that of air; for then there would be no refraction or reflection as the light passed from glass to air.”

“Yes, yes,” said Kemp. “But a man’s not powdered glass!”

“No,” said Griffin. “He’s more transparent!”

“Nonsense!”

“That from a doctor (и это /я слышу/ от врача)! How one forgets (как /легко все/ забывается)! Have you already forgotten your physics, in ten years (неужели вы уже забыли физику за десять лет)? Just think of all the things that are transparent and seem not to be so (просто подумайте обо всех этих вещах, которые прозрачны, но не кажутся таковыми). Paper, for instance, is made up of transparent fibres (бумага, например, состоит из прозрачных волокон), and it is white and opaque only for the same reason (и она белая и непрозрачная только по той же причине) that a powder of glass is white and opaque (по которой стеклянный порошок — белый и непрозрачный). Oil white paper, fill up the interstices between the particles with oil (промаслите белую бумагу, заполните маслом промежутки между ее частицами) so that there is no longer refraction or reflection except at the surfaces (так, чтобы /в ней/ больше не происходило преломления и отражения, кроме как на поверхностях), and it becomes as transparent as glass (и она станет такой же прозрачной, как стекло). And not only paper, but cotton fibre (и не только бумага, но и волокна хлопка), linen fibre (льна), wool fibre (шерстяные волокна), woody fibre (волокна дерева), and bone, Kemp, flesh, Kemp (и кости, Кемп, и плоть, Кемп), hair, Kemp, nails and nerves, Kemp (волосы, ногти и нервы, Кемп), in fact the whole fabric of a man (фактически весь организм человека; fabric — ткань, материя) except the red of his blood and the black pigment of hair (за исключением красных кровяных телец и темного пигмента волос), are all made up of transparent, colourless tissue (состоит из прозрачной, бесцветной ткани). So little suffices to make us visible one to the other (так мало необходимо, чтобы мы могли видеть друг друга; to suffice — быть достаточным, хватать). For the most part the fibres of a living creature are no more opaque than water (по большей части волокна живого существа не более непрозрачны, чем вода = не менее прозрачны, чем вода).”

interstice [In`tq:stIs], fibre [`faIbq], creature [`krJCq]

“That from a doctor! How one forgets! Have you already forgotten your physics, in ten years? Just think of all the things that are transparent and seem not to be so. Paper, for instance, is made up of transparent fibres, and it is white and opaque only for the same reason that a powder of glass is white and opaque. Oil white paper, fill up the interstices between the particles with oil so that there is no longer refraction or reflection except at the surfaces, and it becomes as transparent as glass. And not only paper, but cotton fibre, linen fibre, wool fibre, woody fibre, and bone, Kemp, flesh, Kemp, hair, Kemp, nails and nerves, Kemp, in fact the whole fabric of a man except the red of his blood and the black pigment of hair, are all made up of transparent, colourless tissue. So little suffices to make us visible one to the other. For the most part the fibres of a living creature are no more opaque than water.”

“Great Heavens (Боже мой: «великие небеса»)!” cried Kemp (воскликнул Кемп). “Of course, of course (ну конечно)! I was thinking only last night of the sea larvae and all jelly-fish (только прошлой ночью я думал о морских личинках и всех этих медузах)!”

“ Now you have me (теперь вы понимаете меня)! And all that I knew and had in mind a year after I left London — six years ago (и все это я знал и обдумывал через год после того, как уехал из Лондона — шесть лет назад; to have in mind — помнить, иметь в виду). But I kept it to myself (но я держал это в секрете: «держал при себе»). I had to do my work under frightful disadvantages (мне пришлось работать при ужасных помехах/неудобствах). Oliver, my professor, was a scientific bounder (Оливер, мой профессор, был пройдохой от науки), a journalist by instinct, a thief of ideas (с чутьем журналиста, вором /чужих/ идей) — he was always prying (он все время шпионил; to pry — подглядывать, совать нос в чужие дела; выведывать)! And you know the knavish system of the scientific world (вы знаете жульническую систему, что /царит/ в научном мире; knave — жулик, мошенник, плут; уст. /мальчик-/слуга). I simply would not publish, and let him share my credit (я просто не хотел публиковать /свое открытие/ и позволить ему разделить со мной славу; credit — доверие; хорошая репутация; заслуга, уважение). I went on working (я продолжал работать); I got nearer and nearer making my formula into an experiment, a reality (я подходил все ближе и ближе к превращению своей формулы в эксперимент, в реальность). I told no living soul (я не рассказывал об этом ни единой живой душе), because I meant to flash my work upon the world with crushing effect (потому что хотел ослепить мир своей работой с сокрушительным результатом) and become famous at a blow (и сразу стать известным). I took up the question of pigments to fill up certain gaps (я занялся вопросом пигментов, чтобы заполнить некоторые пробелы). And suddenly, not by design but by accident (и вдруг, не намеренно, но случайно), I made a discovery in physiology (я сделал открытие в физиологии).”

“Yes?”

larva [`lRvq], bounder [`baundq], knavish [`neIvIS], physiology ["fIzI`OlqGI]

“Great Heavens!” cried Kemp. “Of course, of course! I was thinking only last night of the sea larvae and all jelly-fish!”

“ Now you have me! And all that I knew and had in mind a year after I left London — six years ago. But I kept it to myself. I had to do my work under frightful disadvantages. Oliver, my professor, was a scientific bounder, a journalist by instinct, a thief of ideas — he was always prying! And you know the knavish system of the scientific world. I simply would not publish, and let him share my credit. I went on working; I got nearer and nearer making my formula into an experiment, a reality. I told no living soul, because I meant to flash my work upon the world with crushing effect and become famous at a blow. I took up the question of pigments to fill up certain gaps. And suddenly, not by design but by accident, I made a discovery in physiology.”

“Yes?”

“You know the red colouring matter of blood (вам известно красное красящее вещество крови); it can be made white — colourless (оно может быть сделано белым, бесцветным) — and remain with all the functions it has now (и сохранить все функции, какие у него есть)!”

Kemp gave a cry of incredulous amazement (Кемп вскрикнул скептически-изумленно).

The Invisible Man rose and began pacing the little study (Невидимка встал и принялся ходить по маленькому кабинету).

“You may well exclaim (вы вполне можете восклицать = я понимаю ваше удивление). I remember that night (помню ту ночь). It was late at night (была поздняя ночь) — in the daytime one was bothered with the gaping, silly students (днем беспокоили глупые студенты, глазевшие /на меня/, разинув рот) — and I worked then sometimes till dawn (и я работал иногда до рассвета). It came suddenly, splendid and complete in my mind (открытие пришло внезапно, великолепное и законченное в моем уме). I was alone (я был один); the laboratory was still, with the tall lights burning brightly and silently (в лаборатории стояла тишина, высокие лампы горели ярко и безмолвно). In all my great moments I have been alone (во все великие/значительные минуты я /всегда/ один).

blood [blAd], complete [kqm`plJt], laboratory [lq`bOrqt(q)rI]

“You know the red colouring matter of blood; it can be made white — colourless — and remain with all the functions it has now!”

Kemp gave a cry of incredulous amazement.

The Invisible Man rose and began pacing the little study.

“You may well exclaim. I remember that night. It was late at night — in the daytime one was bothered with the gaping, silly students — and I worked then sometimes till dawn. It came suddenly, splendid and complete in my mind. I was alone; the laboratory was still, with the tall lights burning brightly and silently. In all my great moments I have been alone.

‘One could make an animal — a tissue — transparent (можно сделать животное/живое существо — ткань — прозрачным)! One could make it invisible (можно сделать его невидимым)! All except the pigments — I could be invisible (все, кроме пигментов — я мог бы стать невидимым)!’ I said, suddenly realising what it meant to be an albino with such knowledge (сказал я, внезапно осознавая, что значит быть альбиносом, обладая таким знанием). It was overwhelming (я был ошеломлен; to overwhelm — ошеломлять, поражать; переполнять, овладевать /о чувствах/; уст. переворачивать кверх ногами). I left the filtering I was doing (я бросил фильтрование, которым занимался), and went and stared out of the great window at the stars (подошел к большому окну и посмотрел на звезды). ‘I could be invisible (я мог бы быть невидимым)!’ I repeated (повторил я).

“To do such a thing would be to transcend magic (осуществить подобное означало превзойти волшебство). And I beheld, unclouded by doubt (и я увидел, свободный от сомнений; to behold; unclouded — безоблачный; cloud — облако), a magnificent vision of all that invisibility might mean to a man (великолепную картину всего того, что невидимость может означать = дать человеку) — the mystery, the power, the freedom (таинственность, могущество, свободу; power — сила, могущество; власть). Drawbacks I saw none (недостатков я не видел никаких; drawback —препятствие; помеха; недостаток, отрицательная сторона: «тянуть/оттягивание назад»). You have only to think (только подумайте)! And I, a shabby, poverty-struck (я, жалкий, нищий: «пораженный бедностью»; to strike — ударять; поражать), hemmed-in demonstrator (притесняемый лаборант; to hem in — окружать), teaching fools in a provincial college (обучающий дураков в провинциальном колледже), might suddenly become — this (вдруг могу стать этим /невидимым и всемогущим/). I ask you, Kemp if you (я спрашиваю вас = скажите, Кемп, вот если бы вы)... Anyone, I tell you, would have flung himself upon that research (любой, говорю вам = поверьте, принялся бы решительно за такое исследование: «бросился бы…»).

knowledge [`nOlIG], provincial [prq`vInS(q)l], research [rI`sq:C]

‘One could make an animal — a tissue — transparent! One could make it invisible! All except the pigments — I could be invisible!’ I said, suddenly realising what it meant to be an albino with such knowledge. It was overwhelming. I left the filtering I was doing, and went and stared out of the great window at the stars. ‘I could be invisible!’ I repeated.

“To do such a thing would be to transcend magic. And I beheld, unclouded by doubt, a magnificent vision of all that invisibility might mean to a man — the mystery, the power, the freedom. Drawbacks I saw none. You have only to think! And I, a shabby, poverty-struck, hemmed-in demonstrator, teaching fools in a provincial college, might suddenly become — this. I ask you, Kemp if you... Anyone, I tell you, would have flung himself upon that research.

“And I worked three years (я работал три года), and every mountain of difficulty I toiled over showed another from its summit (и каждая гора трудности, которую я преодолевал, открывала другую за своей вершиной = за каждым преодоленным препятствием возникало новое; to toil — усиленно трудиться над /чем-либо/; выполнять тяжелую работу; с трудом продвигаться). The infinite details (бесконечные/несметные детали)! And the exasperation (раздражение)! A professor, a provincial professor, always prying (профессор, провинциальный профессор, который вечно следит за тобой). ‘When are you going to publish this work of yours (когда вы собираетесь опубликовать свою работу)?’ was his everlasting question (был его постоянный: «постоянно продолжающийся» вопрос). And the students, the cramped means (а студенты, а нужда: «стесненные средства»; cramp — спазм, судорога; to cramp — вызывать судорогу, спазмы; ограничивать, связывать, стеснять)! Three years I had of it (три года всего этого…) —

“And after three years of secrecy and exasperation (и после трех лет скрытности и раздражения), I found that to complete it was impossible — impossible (я понял, что завершить исследование невозможно — невозможно).”

“How (почему)?” asked Kemp.

“Money (деньги),” said the Invisible Man, and went again to stare out of the window (сказал Невидимка, снова подошел к окну стал глядеть в него).

He turned around abruptly (он резко обернулся).

“I robbed the old man — robbed my father (я ограбил старика, ограбил своего отца).

“The money was not his, and he shot himself (деньги были не его, и он застрелился).”

mountain [`mauntIn], infinite [`InfInIt], secrecy [`sJkrIsI]

“And I worked three years, and every mountain of difficulty I toiled over showed another from its summit. The infinite details! And the exasperation! A professor, a provincial professor, always prying. ‘When are you going to publish this work of yours?’ was his everlasting question. And the students, the cramped means! Three years I had of it —

“And after three years of secrecy and exasperation, I found that to complete it was impossible — impossible.”

“How?” asked Kemp.

“Money,” said the Invisible Man, and went again to stare out of the window.

He turned around abruptly.

“I robbed the old man — robbed my father.

“The money was not his, and he shot himself.”

|

|

|

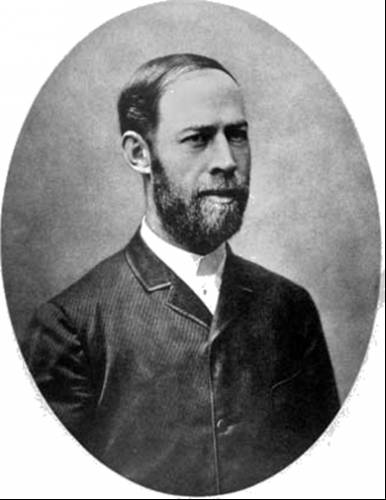

История создания датчика движения: Первый прибор для обнаружения движения был изобретен немецким физиком Генрихом Герцем...

Своеобразие русской архитектуры: Основной материал – дерево – быстрота постройки, но недолговечность и необходимость деления...

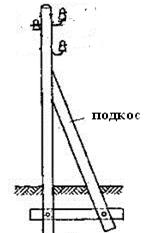

Опора деревянной одностоечной и способы укрепление угловых опор: Опоры ВЛ - конструкции, предназначенные для поддерживания проводов на необходимой высоте над землей, водой...

Поперечные профили набережных и береговой полосы: На городских территориях берегоукрепление проектируют с учетом технических и экономических требований, но особое значение придают эстетическим...

© cyberpedia.su 2017-2024 - Не является автором материалов. Исключительное право сохранено за автором текста.

Если вы не хотите, чтобы данный материал был у нас на сайте, перейдите по ссылке: Нарушение авторских прав. Мы поможем в написании вашей работы!